The Wounded Knee massacre remains one of the darkest and most shameful chapters in American history. On a frozen morning in December 1890, nearly 300 Native Americans—many of them unarmed women and children—were brutally gunned down by the U.S. Army at Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota. Despite being framed by the military as a battle, it was, in reality, a calculated act of suppression and a catastrophic end to centuries of indigenous resistance on the Plains.

This article explores not only the horrific events of that day but also the political climate, cultural misunderstandings, and legacy of the Wounded Knee massacre, which still resonates deeply within Native American communities and among scholars today.

A Powder Keg: U.S. Expansion and Lakota Resistance

By the late 1800s, the U.S. government was fully entrenched in its doctrine of Manifest Destiny—a belief that the nation had a divine right to occupy all lands between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. For the Lakota Sioux and other Plains tribes, this ideology translated into broken treaties, forced relocations, and violent assimilation efforts.

Decades of U.S. military campaigns had reduced Native territories dramatically. The once free-roaming Lakota were confined to reservations with increasingly poor conditions. The buffalo herds, central to Lakota life and culture, were slaughtered almost to extinction by settlers and military hunters. The U.S. government, meanwhile, routinely violated its treaty obligations, withheld food rations, and criminalized cultural practices. The conditions were so dire that they are now seen by human rights historians, including those at the Native American Rights Fund, as part of a systematic campaign of cultural genocide.

The Ghost Dance and the Road to the Wounded Knee Massacre

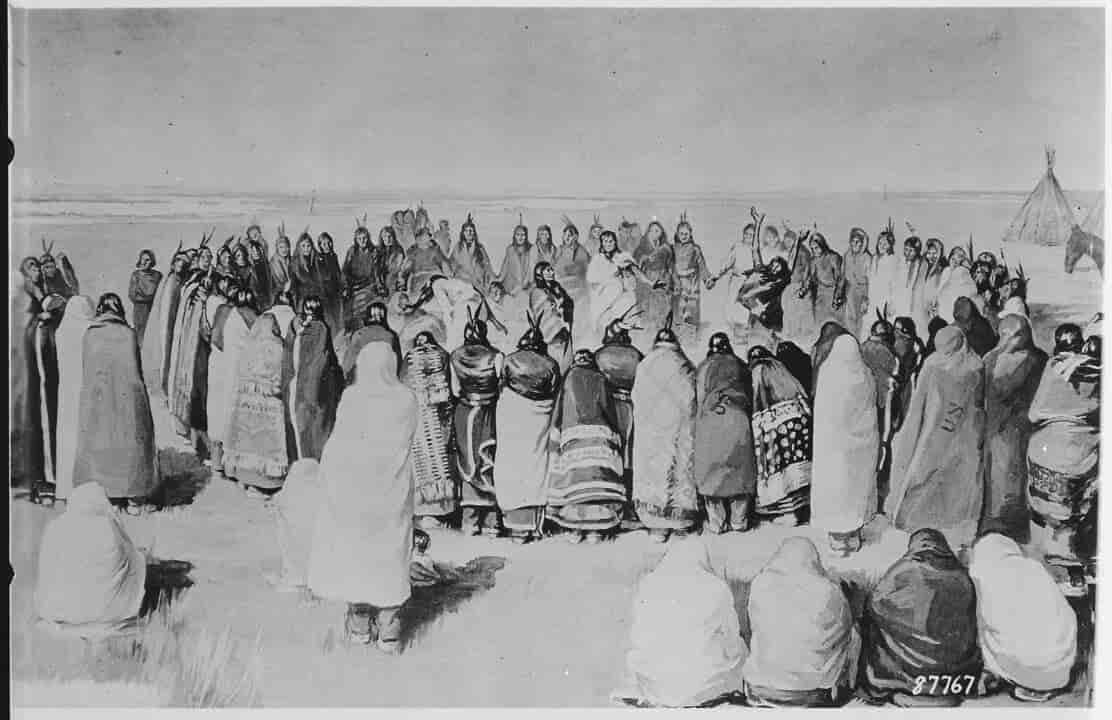

In the face of cultural devastation, a new religious movement began spreading rapidly among western tribes: the Ghost Dance. Introduced by a Northern Paiute prophet named Wovoka, the dance promised a return to traditional life, the reappearance of buffalo, and the removal of colonial powers—if Native peoples danced, prayed, and lived righteously.

To the Lakota, this spiritual revival offered hope in a time of despair. To the U.S. government and nearby settlers, however, the mass dances looked like military drills. The Department of War interpreted these gatherings as a signal of rebellion and ordered the Army to act.

According to reports preserved by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, the Ghost Dance was peaceful in nature and widely misunderstood. The violent response to it exemplifies the long-standing pattern of misinterpreting Native spirituality as a threat.

The Assassination of Sitting Bull

Tensions came to a head on December 15, 1890, when Indian Affairs agents attempted to arrest Sitting Bull, a revered Hunkpapa Lakota leader. Although he was not an active participant in the Ghost Dance, his influence made him a perceived threat. A violent confrontation broke out during the arrest attempt, and Sitting Bull was killed along with several of his supporters.

The assassination shattered hopes for peace. A group of Lakota, led by Chief Spotted Elk (Big Foot), fled their reservation to seek protection at Pine Ridge. Unfortunately, they never made it to safety.

The Final March and Arrival at Wounded Knee

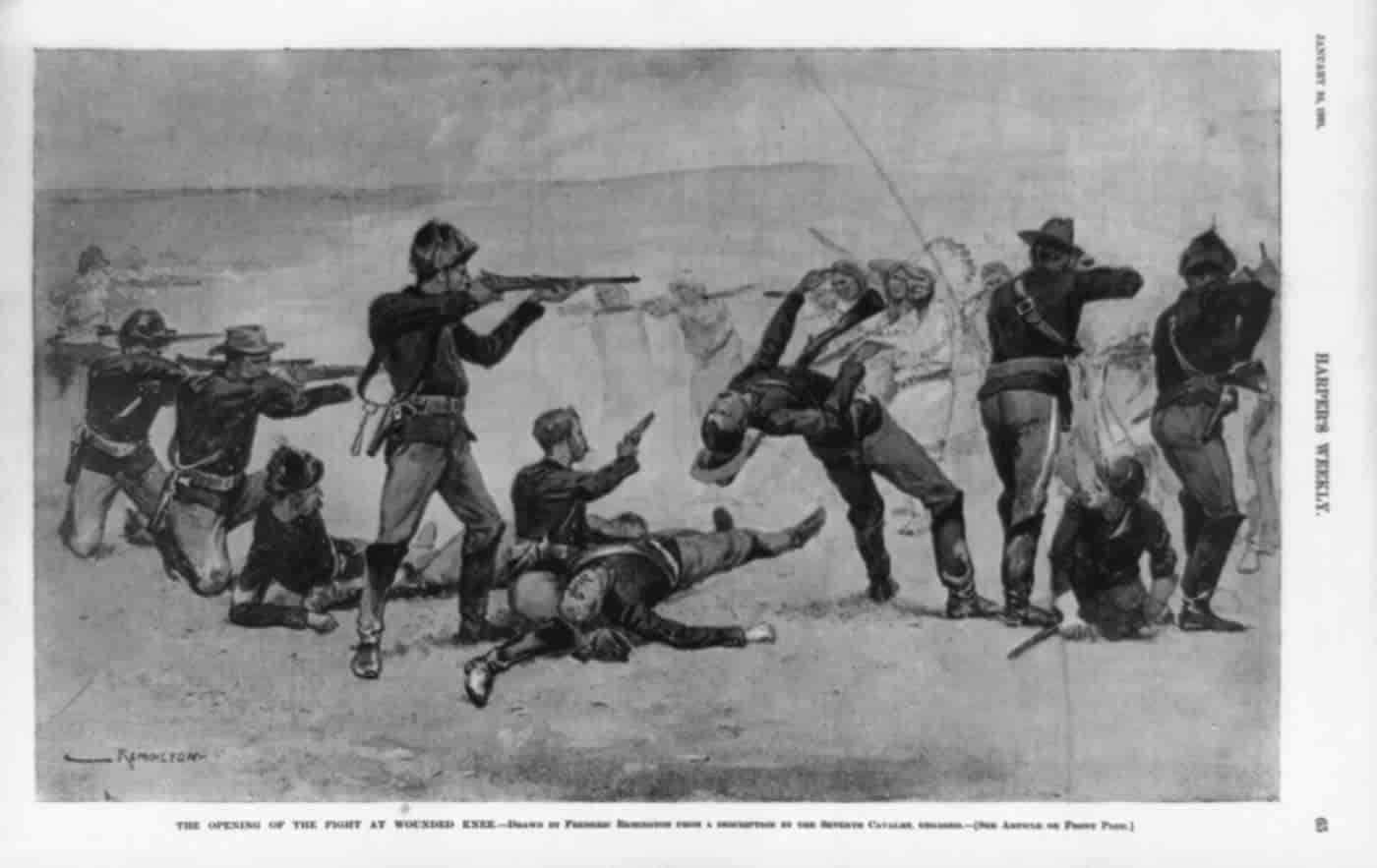

On December 28, the 7th Cavalry Regiment—still haunted by their defeat at Little Bighorn—intercepted Spotted Elk’s group. Despite the freezing temperatures and Spotted Elk’s severe illness, the group was forced to camp near Wounded Knee Creek under heavy military guard. The next morning, December 29, soldiers entered the camp with orders to disarm every man.

What happened next remains one of the most horrific massacres on U.S. soil. During the disarmament process, a scuffle broke out between soldiers and a young deaf Lakota man named Black Coyote, who resisted surrendering his rifle. A shot was fired. Chaos erupted.

The Wounded Knee Massacre and the Slaughter of the Lakota

The Army opened fire. Soldiers fired indiscriminately with rifles and four Hotchkiss cannons positioned on a nearby hill, unleashing explosive shells that tore through tipis and fleeing people. Many Lakota were killed within minutes. Women trying to shield their children were gunned down. Infants were found dead in their mothers’ arms.

Reports collected by researchers at the Library of Congress estimate that between 150 and 300 Lakota Sioux were killed that day, many of them unarmed civilians. Approximately 25 U.S. soldiers also died—many from friendly fire, further highlighting the chaos and lack of control during the assault.

Aftermath: Frozen Bodies and a National Shame

As a brutal blizzard rolled in, the soldiers abandoned the dead where they lay. Days later, when a burial detail returned, they found frozen corpses scattered across the snow-covered field. Women clutched children, elders had fallen mid-prayer, and bodies were grotesquely twisted by death and frost.

Most of the victims were dumped into a mass grave hastily dug by civilians. The site became both a graveyard and a scar—a place of mourning and unresolved grief. Institutions such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum include the Wounded Knee massacre among recognized cases of government-enabled violence against a cultural group.

H2: Legacy of the Wounded Knee Massacre in Native and U.S. History

The Wounded Knee massacre did not fade quietly into history. In 1973, members of the American Indian Movement (AIM) returned to the site and staged a 71-day occupation in protest of federal mistreatment and tribal corruption. The standoff was tense and violent—but it forced America to confront its past.

Today, the site is both a National Historic Landmark and a sacred place of memory. Annual horseback rides and ceremonies commemorate the victims. These events serve as spiritual healing for descendants and as a political reminder that indigenous voices are not forgotten.

Ongoing Debates and Demands

The U.S. government has never formally apologized for the massacre. Adding to the pain, 20 Medals of Honor—the nation’s highest military award—were granted to soldiers involved in the killings. Native leaders continue to petition Congress to rescind these honors. Advocacy groups like Freedom House emphasize that recognition without accountability is insufficient for reconciliation.

Generational Trauma and Cultural Resilience

The Lakota people, like many Native communities, continue to experience the effects of historical trauma—manifested in economic hardship, poor health outcomes, and cultural disruption. Yet, they also demonstrate extraordinary resilience, reviving language, customs, and spiritual practices that had been suppressed for generations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: What caused the Wounded Knee massacre?

Tensions over the Ghost Dance movement, the assassination of Sitting Bull, and military paranoia led to the massacre during a forced disarmament.

Q2: How many were killed during the Wounded Knee massacre?

Between 150 and 300 Lakota Sioux were killed, many of them women and children. Around 25 U.S. soldiers also died, largely from friendly fire.

Q3: Was the Ghost Dance violent?

No. The Ghost Dance was a peaceful spiritual ritual that was misinterpreted by U.S. authorities as militant activity.

Q4: Do the Medals of Honor still stand?

Yes. Despite public outcry and petitions, the Medals of Honor awarded to soldiers involved in the massacre remain officially recognized.

Q5: What is Wounded Knee today?

It is a sacred site for Native Americans and a National Historic Landmark. It remains a place of mourning, memory, and protest.

Q6: Has the U.S. government ever apologized?

No official apology has been made, although various resolutions have acknowledged the tragedy. Native communities continue to demand formal recognition and justice.