In most school textbooks, cell theory is summed up in a few bullet points. All living things are made of cells; cells are the basic units of life. Tucked behind those neat statements is a very human story, and at its centre stands a quiet German physiologist. Theodor Schwann spent long, lonely hours at a microscope in the 1830s, slowly piecing together the idea that animals and plants are built from the same basic units. A careful, modest man, he did not look like a revolutionary, yet the Theodor Schwann biography is in many ways the biography of modern cell biology itself.

This Theodor Schwann biography traces how a printer’s son from Neuss helped turn vague ideas about “living tissues” into a precise framework for understanding life. It follows him from Jesuit classrooms to bustling Berlin laboratories, from theological doubts to arguments over fermentation and spontaneous generation. Along the way, we meet the people who shaped him, the controversies that dogged his reputation, and the legacy that still echoes in every biology lab today.

At a glance: Theodor Schwann

- Who: Theodor Schwann, German physiologist and founder of modern histology.

- Field and era: Experimental biology and physiology in nineteenth-century science.

- Headline contribution: Co-founder of cell theory, extending it to animals and identifying Schwann cells in nerves.

- Why he matters now: His work underpins modern cell biology, neurology and the way we understand disease, making any serious Theodor Schwann biography a window onto the foundations of life science.

Early Life and Education of Theodor Schwann

Childhood in Neuss: a printer’s son with a careful eye

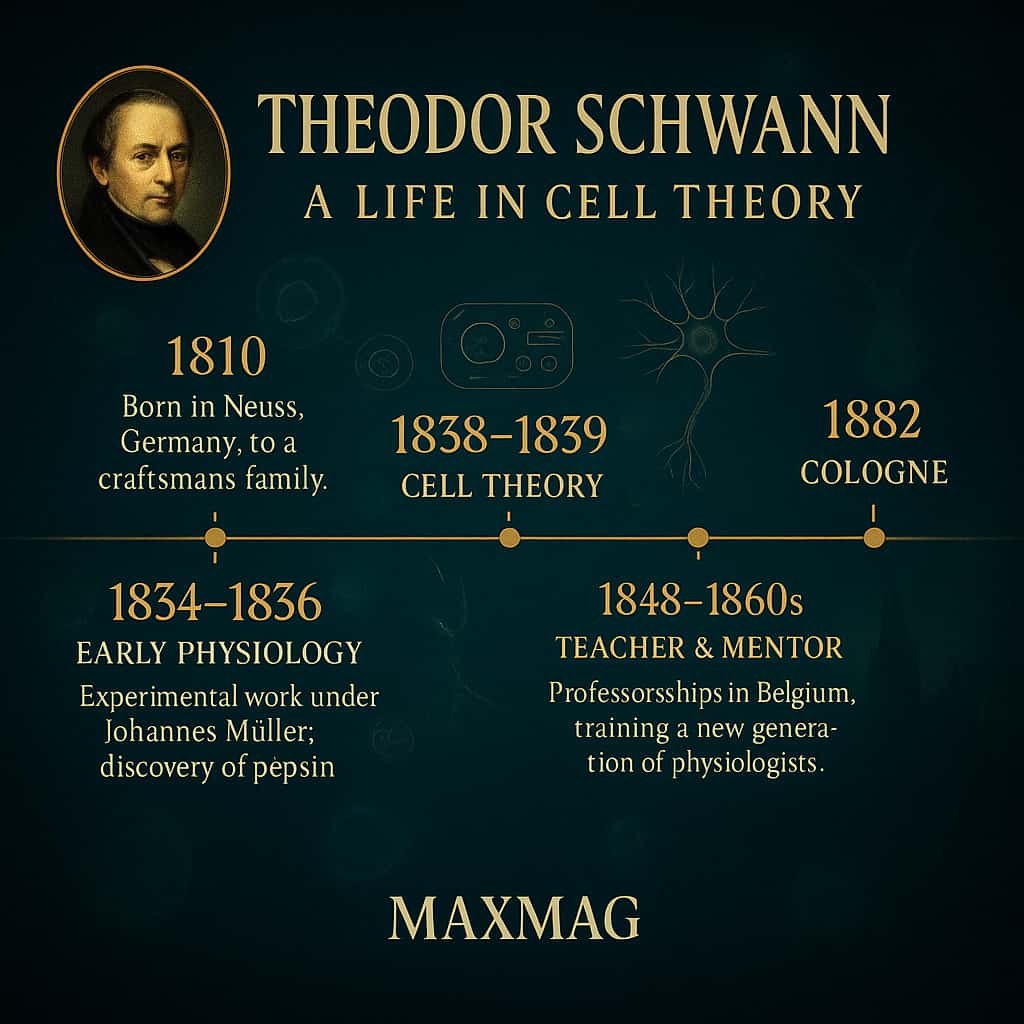

Theodor Schwann was born in 1810 in Neuss, a small town on the Rhine. His father was a goldsmith who later became a printer, and the household atmosphere was one of craftsmanship and precision. Typefaces, metal, paper and ink were part of daily life. For a future cell theory pioneer, it was an early lesson in how tiny details could shape big ideas: a misplaced letter, a misaligned page, a small flaw that changed the meaning of the whole.

Schwann’s family was devoutly Catholic. Religion, duty and discipline were not abstract principles but everyday expectations. As later letters suggest, he experienced his faith as both comfort and burden. The tension between belief and experiment would become one of the quieter threads of any thoughtful Theodor Schwann biography.

Jesuit schooling and the discipline of observation

As a teenager, Schwann attended the Dreikönigsgymnasium in Cologne, a Jesuit school with a strict curriculum. Latin, philosophy and theology dominated, but there was also room for natural philosophy. Teachers emphasised careful observation: the habit of looking closely, of not trusting first impressions. That mental discipline would become invaluable once Schwann turned his eyes to the microscope.

This was not yet a world of professional biologists. “Science” as a career barely existed. For a young man like Schwann, medicine seemed the most practical path to combine intellectual curiosity with a respectable livelihood. But even as he enrolled in medical studies, he carried with him a taste for patient, almost meditative scrutiny—the kind of temperament that a future cell theory pioneer would need.

Universities and mentors: Bonn, Würzburg, Berlin

Schwann began his university studies at Bonn, where he encountered Johannes Müller, a charismatic physiologist who insisted that life could be studied with the same rigour as physics. Müller was building experimental physiology as a discipline, and Schwann was drawn into that orbit. A serious Theodor Schwann biography cannot avoid Müller’s shadow: mentor, taskmaster and model of the new, empirical medicine.

After periods of clinical training in Würzburg and then Berlin, Schwann completed his medical degree under Müller’s supervision. His early research included painstaking experiments on chicken embryos, using custom-built apparatus to control oxygen levels inside incubators. It was delicate work, the opposite of romantic genius. The young scientist was already developing the habits that would define him: meticulous, patient, more interested in slow accumulation of facts than in grand public pronouncements.

By the time he accepted a low-paid assistantship in Müller’s Berlin laboratory, the stage was set. The man who would shape cell theory history was in place; the appropriate question in a Theodor Schwann biography is no longer “if” he would discover something significant, but “what” and “how”.

Theodor Schwann biography and the Birth of Their Big Ideas

In the microscope room: a decisive encounter with Schleiden

One of the most vivid scenes in the Theodor Schwann biography takes place not in a lecture hall but in a cramped microscope room in Berlin. Around 1838, Schwann and the botanist Matthias Schleiden were comparing notes. Schleiden had been studying plant tissues and believed that cells were the basic units of plant life. Schwann, immersed in animal anatomy, had been cataloguing tissues without a single unifying principle.

According to later accounts, the turning point came when Schleiden showed Schwann a drawing of plant cells under the microscope. Schwann was struck by how closely those structures resembled what he had seen in animal cartilage and notochord. It was as if two jigsaw puzzles, long assumed to belong to different sets, suddenly clicked together. The idea that plants and animals might share a common cellular architecture was both simple and radical.

Formulating cell theory: from tissue to unit

Over the next months, Schwann systematically revisited animal tissues. Muscle, nerve, cartilage, even developing embryos—all were examined through the lens of the new idea. Gradually he concluded that animals too were composed of cells or cellular units. This was the birth of classical cell theory: the recognition that the cell is the basic structural and functional unit of life.

For non-specialists, an analogy helps. Imagine trying to understand a vast city by looking only at its neighbourhoods: parks, shopping streets, industrial zones. Cell theory is like discovering that underneath those zones all cities everywhere are built from the same bricks. You can only really grasp how the city works if you understand the bricks and how they are arranged. In the same way, the Theodor Schwann biography is inseparable from the story of how those biological “bricks” came to centre stage.

Mikroskopische Untersuchungen: putting ideas into print

Schwann’s 1839 book, Mikroskopische Untersuchungen über die Übereinstimmung in der Struktur und dem Wachstum der Tiere und Pflanzen, brought these ideas together. Dense, technical and cautious in tone, it is not an easy read today. But this work is where the cell theory pioneer fully articulated that animals and plants are composed of cells and cell products, bringing unity to what had seemed like two separate biological worlds.

For readers who want a clear modern summary of the three classical statements of cell theory, resources such as the National Geographic Education overview of cell theory offer a concise bridge between nineteenth-century science and today’s classroom biology.

In retrospect, the book marks a turning point not just in Theodor Schwann’s life but in the history of biology. From this point on, the Theodor Schwann biography and the story of cell theory history become almost impossible to separate.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Theodor Schwann

Schwann cells and the architecture of nerves

Beyond cell theory, Schwann’s name is attached to a specific structure that every medical student learns: Schwann cells, the glial cells that wrap around peripheral nerves. In painstaking microscopic studies, he described how these cells ensheathe nerve fibres, forming the myelin layers that allow electrical impulses to travel quickly and efficiently.

From the perspective of a modern neurologist, this part of the Theodor Schwann biography reads like the opening act of an ongoing drama. Diseases such as Charcot–Marie–Tooth or certain neuropathies involve damage to Schwann cells, and cutting-edge regenerative medicine still grapples with how to coax them into repairing nerves. The nineteenth-century histology pioneer and today’s neurobiologists are joined by a common set of structures first carefully drawn by a quiet German physiologist.

Pepsin and the chemistry of digestion

In 1836, Schwann isolated a substance from the stomach lining that could digest proteins outside the body. He named it pepsin and showed that it was responsible for breaking down food in gastric juice. At a time when “vital forces” were still fashionable explanations for life, this was a profound step towards a chemical understanding of physiology.

The discovery of pepsin fed into the broader nineteenth-century quest to understand enzymes—mysterious catalysts that sped up reactions in living systems. Historians of science have traced how Schwann’s work fits into that wider story, alongside French and German chemists. A long-form feature in The New Yorker’s exploration of enzyme history places his pepsin experiments within a narrative that stretches from cheese-making to modern detergents, underlining how the “small” steps in a Theodor Schwann biography end up shaping everyday life.

Yeast, fermentation and the death of spontaneous generation

Schwann also turned his microscope on yeast and fermentation. By heating and filtering air, and controlling conditions carefully, he showed that fermentation depended on living yeast cells rather than purely chemical processes or a vague “fermenting principle” in the air. These experiments contributed to the gradual demolition of the old belief in spontaneous generation—the idea that life could arise from non-living matter without any seeds or germs.

While Louis Pasteur would later become the public face of this revolution, a detailed Theodor Schwann biography reminds us that the groundwork was laid by multiple hands. Schwann’s preparations against contamination and his insistence that yeast were living organisms foreshadowed later microbiology. In modern terms, his work represents a critical bridge between early cell theory and the emerging germ theory of disease.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Microscopes as storytelling devices

Nineteenth-century microscopes were finicky instruments. Illumination was uneven, lenses were imperfect and preparation techniques were crude by modern standards. Schwann, however, approached them as disciplined tools rather than magical windows. He spent hours adjusting light, refining stains and cutting ever-thinner slices of tissue, turning the device into a precise instrument of narrative: each slide a scene in the unfolding Theodor Schwann biography of cells.

In an age when some scientists still relied heavily on speculative philosophy, Schwann’s insistence on reproducible microscopic observations was almost stubborn. His notes reveal a mind that preferred incremental certainty over sweeping claims, a working style that helped solidify his reputation as a reliable historian of the body’s smallest parts.

Partnership and rivalry with Matthias Schleiden

The collaboration between Schwann and Schleiden is one of those partnerships that anchors cell theory history. Their famous conversations in Berlin laboratories catalysed the recognition that plant and animal cells shared a common structure. Yet the relationship was not without friction. Later, Schleiden would downplay Schwann’s role, while Schwann’s cautious personality made him less inclined to fight publicly over credit.

For biographers, this dynamic raises rich questions. How much of a scientific breakthrough is an individual achievement, and how much is the product of shared intellectual currents? A nuanced Theodor Schwann biography acknowledges both his intellectual debt to Schleiden and his distinct contribution in extending cellular thinking across the animal kingdom.

Teaching, mentoring and the laboratory as community

When Schwann later took up professorships, notably in Leuven and Liège, his laboratories became training grounds for a new generation of physiologists. Former students remembered him as gentle and approachable, more patient than flamboyant. He may not have built an empire on the scale of some contemporaries, but his role as a mentor is an important secondary thread in the Theodor Schwann legacy.

In these quieter chapters of his life, we see how methods and attitudes spread through teaching as much as through landmark publications. The culture of careful observation and modest interpretation that characterised Schwann’s own work was passed on, cell-like, to the students who would continue to build modern cell biology.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Did Schwann invent cell theory alone?

One common misconception, fed by simplified textbook narratives, is that Schwann single-handedly “invented” cell theory. In reality, the framework emerged from overlapping contributions: Schleiden’s work on plants, Schwann’s extension to animals, and later Rudolf Virchow’s insistence that every cell arises from a pre-existing cell. Any responsible Theodor Schwann biography has to place him within this network rather than on a solitary pedestal.

That said, Schwann’s 1839 synthesis remains a landmark. By unifying plant and animal observations, he provided the conceptual scaffolding on which later refinements were built. The criticism that he did not foresee every aspect of modern cell biology is more a reflection of unrealistic expectations than a serious historical charge.

Religious belief and accusations of reductionism

Another strand of controversy centred on Schwann’s religious beliefs. Some contemporaries worried that a deeply Catholic scientist advancing a “universal cell theory” might smuggle metaphysical assumptions into biology. Others, especially later commentators, accused him of reductionism: of treating living beings as nothing more than collections of tiny parts.

The historical record suggests a more complex picture. Schwann’s letters reveal a man wrestling with how to reconcile faith and scientific evidence. He resisted both the idea that life could be explained entirely in mechanical terms and the notion that religious doctrine should dictate scientific conclusions. In this sense, the Theodor Schwann biography offers a case study in how nineteenth-century science and religion could coexist in tension rather than outright war.

Being overshadowed by later giants

As the nineteenth century progressed, names like Virchow, Pasteur and Koch came to dominate public discussions of cells and disease. Schwann, who moved away from the scientific centres of Berlin and began publishing less frequently, gradually slipped from the spotlight. Some historians argue that his later work lacked the boldness of his early breakthroughs.

Yet to judge him solely by the relative fame of his name is to miss the deeper point. The very possibility of later advances in cellular pathology and microbiology depended on a framework he helped build. In that sense, the quieter latter half of the Theodor Schwann biography does not diminish his role; it simply shows how fast science can move once a powerful idea takes root.

Impact on Biology and on Wider Society

From clinic to classroom: cells as the language of life

Today, whether we are talking about cancer, immunity or brain function, we speak the language of cells. Doctors explain tumours as “cells growing out of control”; public-health campaigns talk about “immune cells” fighting infection. This everyday vocabulary is one of the most visible fruits of the Theodor Schwann legacy. Once life was reconceived in terms of cellular units, it became possible to describe health and disease in those terms too.

In classrooms, diagrams of animal and plant cells, their membranes and nuclei, are standard fare. Few students realise that the symmetry between those two sketches—plant and animal, side by side—is itself a monument to the reasoning captured in any good Theodor Schwann biography.

Enabling modern medicine and biotechnology

The practical impact of cell theory is hard to overstate. Vaccines, antibiotics, stem-cell therapies and much of modern cancer treatment all depend on understanding cells as discrete units that can be targeted, modified or grown. The cell theory pioneer’s insistence that life is built from such units laid the conceptual groundwork for these technologies.

Even high-tech fields like bioelectronics, which aims to interface electronics with living tissues, rest on the idea that cells are the basic actors in living systems. Engineers talking about recording electrical activity from nerve cells or guiding the growth of epithelial sheets are, whether they know it or not, continuing the narrative begun in the Theodor Schwann biography of 1839.

Cultural echoes: the cell as metaphor

Beyond laboratories and hospitals, cells have become cultural metaphors: for prisons, for small social units, for modularity in design. When writers describe society as a “living organism” made up of individual “cells”, they are drawing—sometimes unknowingly—on the conceptual shift that came with Schwann and his contemporaries.

These echoes remind us that scientific theories do not stay confined to specialist journals. The ideas at the heart of the Theodor Schwann biography have seeped into language, politics and art, shaping how we think about individuality and community, freedom and constraint.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

A modest temperament in an age of flamboyant science

Contemporary descriptions portray Schwann as gentle, reserved and almost self-effacing. In an era when some scientists cultivated dramatic public personas, he remained wary of self-promotion. That modesty partly explains why later histories of cell theory sometimes relegate him to the background.

Yet students and colleagues often emphasised his kindness and patience. In private correspondence, we see flashes of humour and occasional frustration, but rarely bitterness. The human texture of the Theodor Schwann biography lies as much in these small, quiet details as in the grand scientific milestones.

Faith, doubt and the meaning of life’s “units”

Schwann’s Catholic upbringing never entirely left him. He attended Mass, engaged with theological debates and wrestled with questions about the soul and free will. For him, recognising cells as life’s basic structural units did not automatically negate the idea of a spiritual dimension. Instead, he seems to have regarded his work as uncovering the mechanisms through which a divinely ordered world operated.

This stance can be difficult to categorise in modern terms. He was neither a dogmatic believer who rejected uncomfortable evidence, nor a materialist who denied anything beyond atoms and cells. In that complexity, the Theodor Schwann biography mirrors the broader struggle of nineteenth-century science to find its ethical and philosophical bearings.

Friendships, disappointments and late recognition

Over the years, Schwann maintained friendships with fellow scientists across Europe, exchanging letters that mixed technical discussion with personal news. But there were also disappointments: grants that did not materialise, positions that went to more politically connected rivals, the slow fade of public recognition as newer names came to the fore.

Late in life, honours such as prestigious medals acknowledged his role in shaping biology. Yet one senses from surviving documents that he never fully embraced the heroic narrative. The Theodor Schwann biography, as he might have told it, would have been less about glory and more about the patient joy of seeing the hidden structures of life come into focus.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Theodor Schwann

Leuven and Liège: working on the margins of the centre

After his Berlin years, Schwann accepted positions in Belgian universities, including Leuven and later Liège. These posts offered stability and the chance to build his own teaching programmes, but they also placed him slightly off the main German scientific stage. As cell biology and pathology exploded elsewhere, he watched from a relative distance.

He continued to teach and to carry out research, though at a slower pace. Some of his later work wandered into less fruitful territory, reflecting the difficulty of staying at the cutting edge in a rapidly changing field. Still, students who encountered him in these years met a seasoned histology pioneer whose lectures bore the weight of lived experience.

Illness, death and early biographical sketches

Schwann died in 1882 in Cologne. Early biographical notices, often written by colleagues, tended to focus on his most famous achievements: the 1839 formulation of cell theory and the discovery of Schwann cells. They framed him as a key figure in nineteenth-century science but sometimes glossed over the inner struggles and quieter virtues that make a modern Theodor Schwann biography compelling.

Only later historians began to explore his notebooks, correspondence and lesser-known writings, reconstructing a fuller portrait: an experimentalist who lived through the transition from vitalist speculation to laboratory-based biology, and who helped steer that transition with remarkable steadiness.

How his story looks from the twenty-first century

From today’s vantage point, Schwann’s life appears both distant and familiar. The tools have changed utterly: electron microscopes, fluorescence imaging, molecular genetics. Yet the questions that drove him—What is life made of? How do structure and function relate?—remain at the heart of biological research.

In that sense, the final chapters of a Theodor Schwann biography are still being written, not in history books but in laboratories, classrooms and clinics that continue to use his cellular framework as their starting point.

The Lasting Legacy of Theodor Schwann biography

Why his ideas still anchor modern cell biology

Strip away the complexity of modern genomics and imaging technologies, and the core picture of life that students learn today would still be recognisable to Schwann. Cells as basic units; tissues as organised collections of cells; organisms as intricate federations of those units. This continuity is one of the most striking aspects of the Theodor Schwann biography for contemporary readers.

Of course, we now know that cells communicate through elaborate networks, that their internal machinery is staggeringly complex, and that exceptions to textbook rules abound. But the decision to focus on cells in the first place—to make them the “atoms of life” for biological thinking—is a legacy of Schwann’s nineteenth-century synthesis.

Understanding more than a single scientist

Engaging seriously with a Theodor Schwann biography does more than illuminate one man’s achievements. It offers a window onto how scientific revolutions actually happen: not as sudden, solitary flashes of insight, but as the slow coalescing of observations, conversations and careful experiments.

It also shows how ideas travel. Concepts hammered out in cramped Berlin laboratories now underpin public-health policies, medical treatments and even everyday metaphors about “cells” of resistance or “cellular” networks. To follow Schwann’s journey is to watch the construction of a mental world we now take for granted.

Ultimately, the enduring power of the Theodor Schwann biography lies in what it reveals about our own. To understand his focused keyword story of cells is to better understand why we think about bodies—and perhaps societies—as structured wholes built from tiny, interconnected parts. That perspective continues to shape debates about health, identity and responsibility in the twenty-first century, reminding us that cell theory is not just a chapter in biology textbooks but a way of seeing the world.

Frequently Asked Questions about Theodor Schwann biography

Q1: Who was Theodor Schwann in the history of biology?

Q2: What does the term “Theodor Schwann biography” usually focus on?

Q3: Why is Theodor Schwann considered a cell theory pioneer?

Q4: What are Schwann cells, and why are they important?

Q5: How did Theodor Schwann’s discovery of pepsin change physiology?

Q6: What is the lasting legacy of Theodor Schwann biography for modern science?