Spinoza philosophy of nature redefined the boundaries between divinity, reason, and the natural world. Unlike most religious or philosophical systems of his time, Spinoza didn’t place God outside or above the universe—he placed God within it. For Spinoza, nature and God were not two distinct entities but the same eternal substance. His work laid the foundation for a radical new metaphysics that continues to influence modern science, ethics, and political thought.

A Brief Life That Left a Lasting Mark

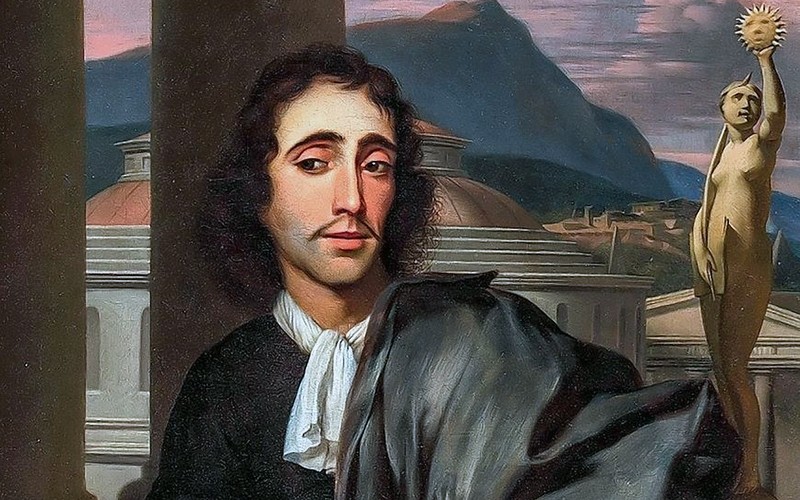

Baruch Spinoza was born in Amsterdam in 1632 to a Portuguese-Jewish family that had fled the Inquisition. A prodigy in religious education, he studied Talmud and Torah deeply but began to question the teachings early. In 1656, at age 23, he was excommunicated by the local Jewish authorities—a punishment that still technically stands today.

Freed from communal expectations, Spinoza lived simply as a lens grinder and dedicated his life to philosophy. He died at only 45, possibly from lung issues linked to fine glass dust. His masterwork, Ethics, was published posthumously and has since become a cornerstone of rationalist philosophy.

The Divine Substance: God and Nature Are One

Spinoza rejected the notion of a supernatural God who intervenes in the world. Instead, his philosophy of nature equated God with the totality of existence. There is only one substance, he argued—eternal, infinite, and self-caused. That substance is both God and Nature (Deus sive Natura).

Everything else—trees, animals, stars, thoughts—is merely a “mode” or expression of that substance. This bold move overturned centuries of theological doctrine and introduced a new kind of pantheism that placed nature at the heart of divinity.

You can explore the implications of this idea in the detailed Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on Spinoza.

No Mind-Body Dualism, Only Unity

Spinoza also rejected the Cartesian separation between mind and body. In his system, mind and body are not two different things—they are two ways of perceiving the same underlying reality. Thought and extension are attributes of one unified substance.

This eliminated the “interaction problem” that plagued dualist philosophies. For Spinoza, there’s no gap between mind and matter because they’re one and the same seen from different angles.

This framework became foundational in later developments in psychology and neuroscience, where the mind-body connection is viewed as deeply intertwined.

Emotions, Power, and the Path to Joy

In Ethics, Spinoza turned his attention to human psychology. His goal? To show that by understanding our emotions, we could move from passive suffering to active joy. He classified emotions based on whether they arise from within (active) or from external causes (passive).

For instance:

-

Joy is the feeling of moving toward greater perfection.

-

Sadness is moving away from it.

-

Love is joy attached to an external cause.

-

Hatred is sadness caused by an external idea.

Spinoza didn’t say we should suppress emotions—but understand them. By recognizing the causes behind our passions, we can regain control over them.

For a modern take, The New Yorker offers a rich piece on Spinoza’s vision of emotional freedom, particularly how it resonates with today’s therapeutic and political landscape.

Freedom Through Understanding

Spinoza argued that freedom isn’t about doing whatever we want. Instead, freedom is understanding necessity. When we grasp how the world works—and how we fit into it—we can align ourselves with nature’s flow rather than fight it.

He called this way of seeing the world “sub specie aeternitatis”—under the aspect of eternity. When we understand our place in the infinite whole, we no longer blame fate or gods for our suffering. We accept, understand, and act wisely.

The more we comprehend the causes of things—including our emotions—the more free we become. And the more free we are, the closer we come to lasting joy, or what Spinoza calls blessedness.

Spinoza’s Political and Religious Legacy

Spinoza’s philosophy of nature wasn’t just metaphysical—it had radical implications for religion and politics. In his Theological-Political Treatise, he argued that governments must allow freedom of thought and protect citizens from religious coercion.

He warned that religious authorities often stifle reason to maintain control. True faith, he said, is not obedience—it’s understanding. And democracy, with its foundation in open debate and equal voice, is the best system for preserving this freedom.

These ideas would later influence Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke and shaped modern secular governance. For historical background, Britannica’s article on Spinoza provides a comprehensive summary of his intellectual impact.

Why Spinoza Still Matters

Spinoza is now considered one of the founders of modern philosophy. His work influenced figures as diverse as Einstein, Nietzsche, Freud, and Deleuze. His emphasis on reason, emotional insight, and the unity of all things resonates with many contemporary fields—from environmental ethics to cognitive science.

In an age of anxiety and division, his call to understand the world instead of fearing it feels more urgent than ever.

FAQ

Q: What is Spinoza’s philosophy of nature in simple terms?

It’s the belief that God and nature are one and the same. Everything that exists is part of a single, eternal, divine substance.

Q: Why did Spinoza reject traditional religion?

Because he believed most religious beliefs were based on fear and misunderstanding, not reason. He advocated for rational insight over dogma.

Q: What does Spinoza mean by “freedom”?

Freedom, for Spinoza, is understanding the causes of things and acting according to our rational nature—not being ruled by emotions.

Q: How did Spinoza view emotions?

As natural phenomena that can enslave or liberate us depending on our understanding. Joy arises when we comprehend our place in nature.

Q: Was Spinoza an atheist?

Not exactly. He believed in God—but not as a person. His God is nature itself, governed by eternal, rational laws.