In the crowded history of twentieth-century science, the Salvador Luria biography reads almost like a novel. A young Jewish physician from Turin, pushed out of Fascist Italy by racist laws, crosses borders and oceans with a suitcase full of books and a head full of questions about life itself. In exile he discovers viruses that attack bacteria, helps create the new field of molecular biology, and becomes a voice of conscience about how science should be used. It is a story of courage, curiosity and moral struggle that still speaks to today’s debates about research and responsibility.

Before he shared a Nobel Prize and helped launch a revolution in genetics, Salvador Luria was simply a bright, restless student who did not quite fit the expectations of his time. The Salvador Luria biography is also the story of a man who kept reinventing himself: from medical student to physicist manqué, from bacteriophage pioneer to outspoken critic of nuclear weapons, from immigrant outsider to revered mentor of a new generation of biologists.

Salvador Luria biography at a glance

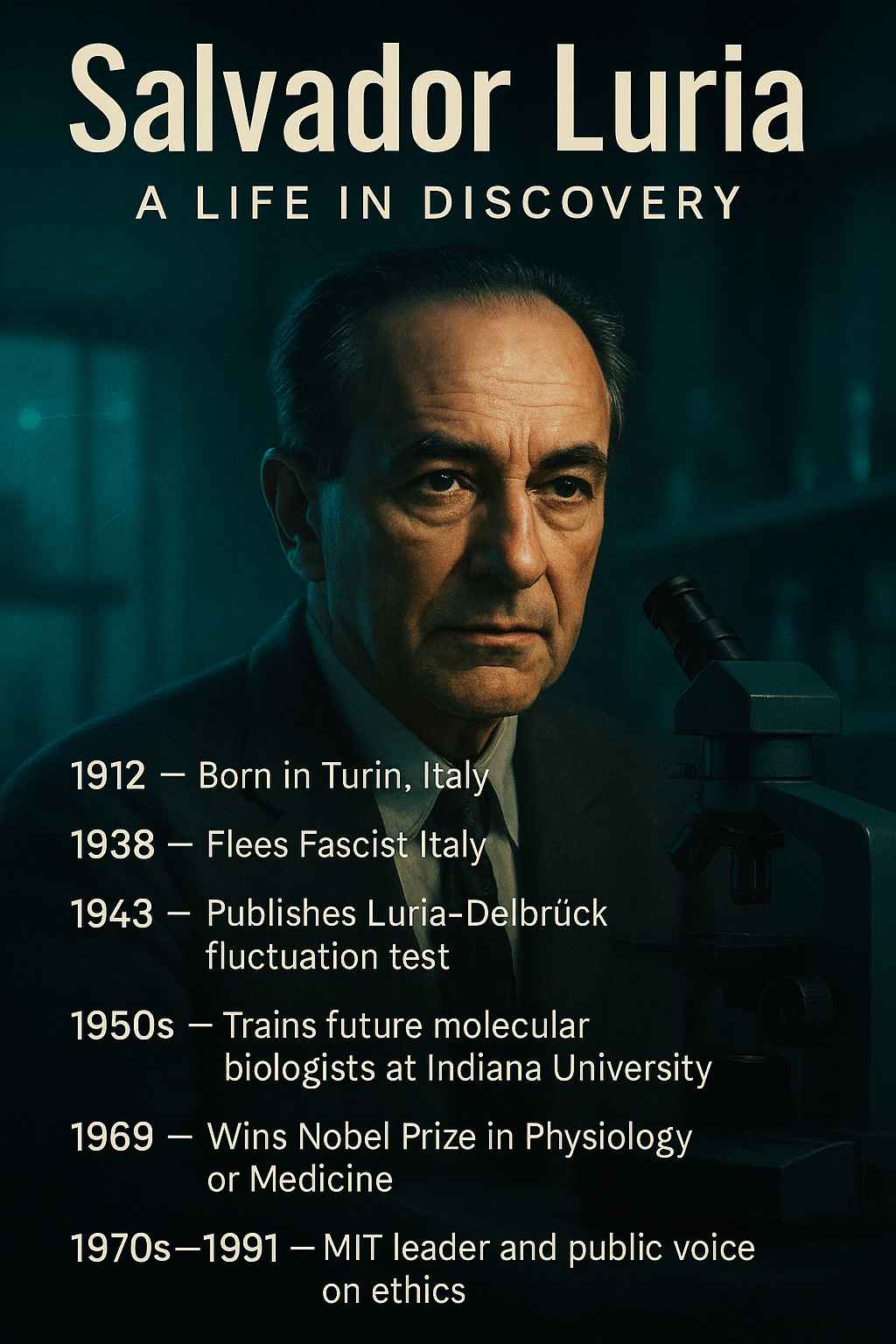

- Who: Salvador Edward Luria (1912–1991), Italian-American microbiologist and molecular biology pioneer.

- Field and era: Bacteriophage research and early genetics in the mid-twentieth century.

- Headline contribution: Co-author of the Luria–Delbrück fluctuation test, proving that bacterial mutations arise randomly rather than in response to need.

- Why he matters today: His work underpins modern antibiotic resistance studies and the wider history of molecular biology, while his activism shaped debates about science and society.

Early Life and Education in the Salvador Luria biography

From Turin to exile: the first chapter of the Salvador Luria biography

Salvador Edward Luria was born in 1912 in Turin, in northern Italy, into a middle-class Jewish family. His father was an accountant, his mother had a literary bent, and the young Luria grew up in a household where books were taken seriously. Like many characters in a classic Salvador Luria biography, the boy who would one day help found molecular biology did not initially plan to be a scientist at all. He considered engineering, flirted with physics and finally settled on medicine at the University of Turin.

At Turin, he studied under the influential physiologist Giuseppe Levi, whose laboratory also trained future Nobel laureates Rita Levi-Montalcini and Renato Dulbecco. The atmosphere was rigorous but encouraging: students were not only expected to learn facts, but also to argue, question and design their own experiments. This early immersion in experimental thinking would later shape Luria’s role as a molecular biology pioneer, someone who constantly looked for clever ways to test deep questions about life.

Anti-Semitic laws and a forced decision

The rise of Benito Mussolini and the tightening alliance with Nazi Germany turned this promising academic path into a dead end. In 1938, Fascist Italy introduced racial laws that stripped Jewish citizens of their university positions and civil rights. For Luria, the impact was immediate and brutal: his fellowship was cancelled, his career as a physician-scientist in Italy was effectively over. The next pages in the Salvador Luria biography would be written in exile.

He left Italy for Paris, where he tried to rebuild his life in a foreign language and a rapidly deteriorating political climate. In Paris he encountered the emerging world of radiation biology and the idea that genes could be physically altered by X-rays. These conversations nudged him closer to genetics and to the kind of questions that would later define the Salvador Luria biography: How stable is heredity? How do mutations really arise?

Escape to the United States

When German troops advanced on Paris in 1940, Luria joined the stream of refugees heading south. Eventually he obtained a visa for the United States, arriving with little money and no secure job. In New York and then at Columbia University, he entered a network of European émigré scientists who were reshaping American science. It was here that the future Nobel laureate began to transform from a displaced doctor into a full-fledged researcher in bacteriophage genetics, a key turning point in any thoughtful Salvador Luria biography.

That mixture of instability and opportunity left a lasting mark on his outlook. Throughout his life, Luria remained acutely aware of how politics could distort science and how fragile careers could be. Many later episodes in the Salvador Luria biography—from his opposition to nuclear weapons to his support for younger colleagues—can be traced back to these formative years of loss and reinvention.

Salvador Luria biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

Discovering bacteriophages and a new experimental world

In the early 1940s, Luria discovered what would become his scientific home: bacteriophages, the viruses that infect bacteria. These tiny entities, just DNA inside a protein shell, looked like perfect tools for dissecting the deepest questions in genetics. The Salvador Luria biography is inseparable from this choice. Where others saw obscure microbes, he saw a simplified, almost minimalist universe in which to test how genes work.

Working first at Columbia and then at Indiana University, Luria joined forces with another immigrant scientist, the German-born physicist-turned-biologist Max Delbrück. Together they helped create what later historians would call the “phage group,” a loose international community of molecular biology pioneers who used bacteriophages as model systems. For students of the history of molecular biology, it is impossible to separate the story of the phage group from any serious Salvador Luria biography.

The Luria–Delbrück fluctuation test in the Salvador Luria biography

Their most famous achievement, and the centrepiece of many accounts of the Salvador Luria biography, was the Luria–Delbrück fluctuation test, published in 1943. At the heart of the test lay a deceptively simple question: When bacteria become resistant to a virus or a chemical, do they change because of the challenge, or do random mutations arise first and only later prove useful?

Luria and Delbrück grew many small cultures of bacteria and then exposed them all to the same virus. If resistance arose because of exposure, every culture should have produced a similar number of resistant colonies. Instead, they found wild fluctuations: some cultures produced many resistant bacteria, others almost none. The pattern was exactly what you would expect if mutations occurred randomly, long before the virus appeared. Their fluctuation experiment became a cornerstone in the history of genetics and is often cited in textbooks and in university courses on bacterial evolution as a classic result of twentieth-century biomedicine.

For non-specialists, one way to grasp the insight of this key moment in the Salvador Luria biography is to think about lottery tickets. Mutations are like tickets bought in advance, without knowing which future “draw” will make them valuable. Natural selection then simply chooses the winners. This shift from purpose-driven change to random variation under selection was crucial evidence for the modern view of evolution at the microscopic level.

Recognition and an emerging reputation

Even before he won the Nobel Prize, Luria’s work had made him a central figure in the history of molecular biology. His fluctuation test and later studies of phage-host interactions showed that viruses and bacteria could be used to probe gene function with mathematical precision. In a sense, the Salvador Luria biography illustrates how big theoretical questions about life can be answered through small, tightly designed experiments.

Key Works and Major Contributions in the Salvador Luria biography

Exploring viral replication and genetic control

After the war, Luria continued to refine bacteriophage research, exploring how viruses reproduce inside bacterial cells and how genetic control works at the molecular level. These studies fed directly into the emerging framework of DNA as the genetic material and the genetic code. While he did not work alone—his collaborators included Delbrück, Alfred Hershey and many younger scientists—any serious Salvador Luria biography must place him among the architects of the molecular view of life.

He helped show how certain phages can integrate their DNA into bacterial chromosomes, lying dormant before reactivating. This phenomenon, known as lysogeny, became a key model for understanding gene regulation: how some genes can switch on and off in response to internal or external signals. For students of molecular biology history, these experiments are more than technical details; they are steps in a larger shift from descriptive biology to a quantitative, mechanistic science.

Shaping the early history of molecular biology

Luria’s laboratory became a training ground for future leaders. James Watson, who would co-discover the double helix structure of DNA, completed his PhD under Luria at Indiana University. Many other students and postdocs carried the ideas and methods developed in his lab to new fields, from cancer research to virology. In this sense, the Salvador Luria biography is also the story of a teacher whose impact radiated outward through generations.

He contributed to major conferences and summer schools, including sessions at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, which served as a kind of informal parliament for molecular biology pioneers. There, debates over experiments and theories were as intense as any political argument. The early Cold Spring Harbor meetings are now part of the standard history of molecular biology, and Luria’s presence in those rooms shows how central he was to the field’s direction.

“Life: The Unfinished Experiment” and public science writing

In 1973, Luria published a book aimed at general readers, Life: The Unfinished Experiment. This work deserves a place in any rounded Salvador Luria biography because it shows another side of him: the science explainer and public intellectual. The book traces the story of life on Earth and the development of modern molecular biology in an accessible, often poetic style. It helped bring complex ideas about DNA, viruses and evolution to a wider audience just as genetic engineering was beginning to capture headlines.

By the 1970s, Luria had also taken on major institutional roles, particularly at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he helped build a strong programme in microbiology and molecular genetics. For readers who want a deeper institutional context, MIT’s own history of biology provides a useful backdrop and timeline of these changes, for example in its history of biology at MIT. Such resources complement the narrative of the Salvador Luria biography by showing how his individual career intersected with the growth of American research universities.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

The phage group and a collaborative culture

Unlike the stereotype of the lone genius, the Salvador Luria biography is filled with collaborators, students and colleagues. The phage group was famously informal: information flowed through letters, shared strains of bacteria and viruses, and intense discussions at conferences. Luria’s own working style combined rigour with a sense of play; he liked clever experiments that turned a deep question into a simple read-out, such as counting bacterial colonies on a plate.

This collaborative, almost communal culture was crucial for the field. Luria’s willingness to share ideas and materials made it easier for others to reproduce and extend his work. Many historians of science now see the phage group as a model for how small, tightly knit communities can accelerate innovation, and the Salvador Luria biography offers a vivid case study of that model in action.

A mentor who demanded clarity

Former students remember Luria as a demanding but supportive mentor. He insisted that experiments be designed with clear hypotheses and that results be interpreted with mathematical care. At the same time, he encouraged creative risk-taking. In the broader story of twentieth-century science education, the Salvador Luria biography illustrates how immigrant scientists helped redefine American graduate training, making it more research-intensive and internationally connected.

His letters and recollections suggest a man who could be impatient with sloppy thinking but deeply loyal to those who shared his seriousness. This combination of sharp criticism and personal generosity helped forge a distinctive laboratory culture that many of his students carried into their own careers.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Science, politics and the Cold War climate

No honest Salvador Luria biography can ignore his political commitments. Having experienced Fascism first-hand, he was wary of any alliance between science and authoritarian power. In the United States during the early Cold War, he joined organisations that opposed nuclear weapons and supported civil liberties. This political engagement brought criticism from some colleagues who preferred a more “neutral” image of science.

Luria argued that researchers could not stand apart from the uses of their work. As molecular biology pioneers began to explore genetic engineering, he warned that social and ethical questions needed to be taken seriously. His stance foreshadowed later debates about recombinant DNA, biotechnology and bioethics, themes that still echo whenever new tools such as CRISPR are discussed.

Misunderstandings about bacterial evolution

One common misconception that the Salvador Luria biography helps to dispel concerns how bacteria and other microbes evolve resistance. Even today, popular accounts sometimes suggest that pathogens “learn” to resist drugs because they are exposed to them. Luria’s fluctuation test showed that this is backwards: mutations occur randomly, and treatment merely selects those already-mutant cells that happen to survive.

Understanding this point is not just a historical curiosity. In the era of rising antibiotic resistance, the insight at the heart of the Luria–Delbrück experiment remains central to public health. It explains why misuse of antibiotics is so dangerous: every unnecessary exposure gives random mutants a better chance to take over.

Impact on Molecular Biology and on Wider Society

From basic research to medical implications

The basic principles uncovered in the experiments that fill any serious Salvador Luria biography have far-reaching consequences. By clarifying how mutations arise and how viruses replicate, Luria and his colleagues laid foundations for understanding cancer, viral diseases and the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Many modern laboratory techniques, from plaque assays to genetic mapping in microbes, descended from methods refined in his circle.

In this sense, the history of molecular biology is not an abstract tale of test tubes and equations; it is a story that shapes how we fight infections and design therapies. When doctors adjust antibiotic regimens or epidemiologists model the spread of resistant strains, they are working in a world structured by insights that trace back, in part, to the experiments central to the Salvador Luria biography.

A public voice in debates about science

Luria’s impact extended beyond the laboratory. He wrote essays and gave lectures on the social responsibility of scientists, arguing that technical expertise carried moral obligations. During the Vietnam War, for example, he criticised the use of science in weapons development and urged students to think critically about the institutions they served.

Obituaries in major newspapers stressed this dual identity: Luria as both Nobel-winning microbiologist and engaged citizen. A striking example is a New York Times obituary highlighting his scientific and civic roles, which mirrors the way many modern historians frame the Salvador Luria biography as the story of a scientist who refused to separate facts from values.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Humour, music and a European sensibility

Behind the formal portraits and prize citations, the Salvador Luria biography reveals a man with a dry sense of humour and a strong attachment to European culture. Friends and students recall evenings of conversation that ranged from experimental design to literature and music. He loved classical composers, especially those whose work balanced rigorous structure with emotional depth—perhaps a reflection of his own approach to science.

His refugee experience never left him. Even after decades in the United States, he retained a marked accent and an outsider’s eye on American society. This distance may have made it easier for him to question scientific and political orthodoxies, and it gave his lectures a distinctive blend of charm and seriousness.

Family life and personal resilience

Luria married and had a son, balancing family responsibilities with a demanding research and teaching schedule. Like many scientists of his generation, he spent long hours in the lab, yet letters from former students suggest that he made time for informal gatherings and personal conversations. Those who appear in the inner pages of the Salvador Luria biography remember not just a famous name but a mentor who listened carefully and argued vigorously.

Illnesses and professional setbacks did occur, especially during the tense political periods of the 1950s and 1960s, but he tended to frame these challenges in the larger context of history. Having survived Fascism and war, he regarded ordinary academic frustrations as manageable problems.

Later Years and the Final Chapter of Salvador Luria’s Life

Nobel recognition and institutional leadership

In 1969, Luria shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Max Delbrück and Alfred Hershey “for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses.” This formal recognition marked a high point in the Salvador Luria biography, but it did not end his scientific or public engagement. At MIT he helped establish the Center for Cancer Research, drawing together biologists, clinicians and physicists to tackle one of the central medical problems of the age.

As a molecular biology pioneer now firmly embedded in the American research establishment, he used his influence to support younger colleagues and to defend academic freedom. His dual status as an institutional leader and a former refugee gave him a distinctive voice in debates over university governance and research funding.

Writing, reflection and a broad view of science

In his later years, Luria devoted more time to writing and reflection. He continued to revise Life: The Unfinished Experiment and to contribute essays on the history of molecular biology and the changing relationship between science and society. These reflective writings add depth to the Salvador Luria biography, revealing how he understood his own journey and the broader trajectory of twentieth-century biology.

He died in 1991 in Lexington, Massachusetts, leaving behind not only a body of scientific work but also a distinctive intellectual and ethical legacy. For those who study the history of modern biology, the closing chapter of the Salvador Luria biography is less about endings than about the questions his life continues to raise.

The Lasting Legacy of the Salvador Luria biography

Lessons for today’s genetics and medicine

What, then, does the Salvador Luria biography offer to readers facing today’s scientific and medical challenges? At the technical level, his work reminds us that deep insights can emerge from simple, well-designed experiments. At the conceptual level, it underscores the importance of randomness and selection in evolution—a framework that remains central in cancer biology, virology and studies of antibiotic resistance.

His life also offers a model of how a scientist can engage with the world: rigorous in the lab, outspoken in public, and attentive to the ethical dimensions of new technologies. The story traced through the many episodes of the Salvador Luria biography helps explain why debates about genetic engineering, dual-use research or pandemic preparedness cannot be left to technical experts alone.

A human story behind the equations

Perhaps most importantly, the Salvador Luria biography restores a human face to the early days of molecular biology. It reminds us that this now-dominant scientific worldview was built not just on data and equations, but also on the experiences of refugees, immigrants and dissidents who carried their histories with them into the laboratory. In this sense, understanding the Salvador Luria biography helps us understand something larger about how science grows out of specific lives, places and political moments.

In our current era of rapid biotechnological change, looking back at the Salvador Luria biography is not an exercise in nostalgia. It is a way to ground present debates in the hard-won insights of a scientist who thought deeply about both molecules and morals.

Frequently Asked Questions about Salvador Luria biography

Q1: Who was Salvador Luria and why is the Salvador Luria biography important?

Q2: What is the Luria–Delbrück fluctuation test mentioned in most Salvador Luria biography accounts?

Q3: How did Salvador Luria become a molecular biology pioneer after leaving Italy?

Q4: What role did teaching and mentoring play in the Salvador Luria biography?

Q5: How did Salvador Luria view the social responsibilities of scientists?

Q6: What can today’s readers learn from the Salvador Luria biography?