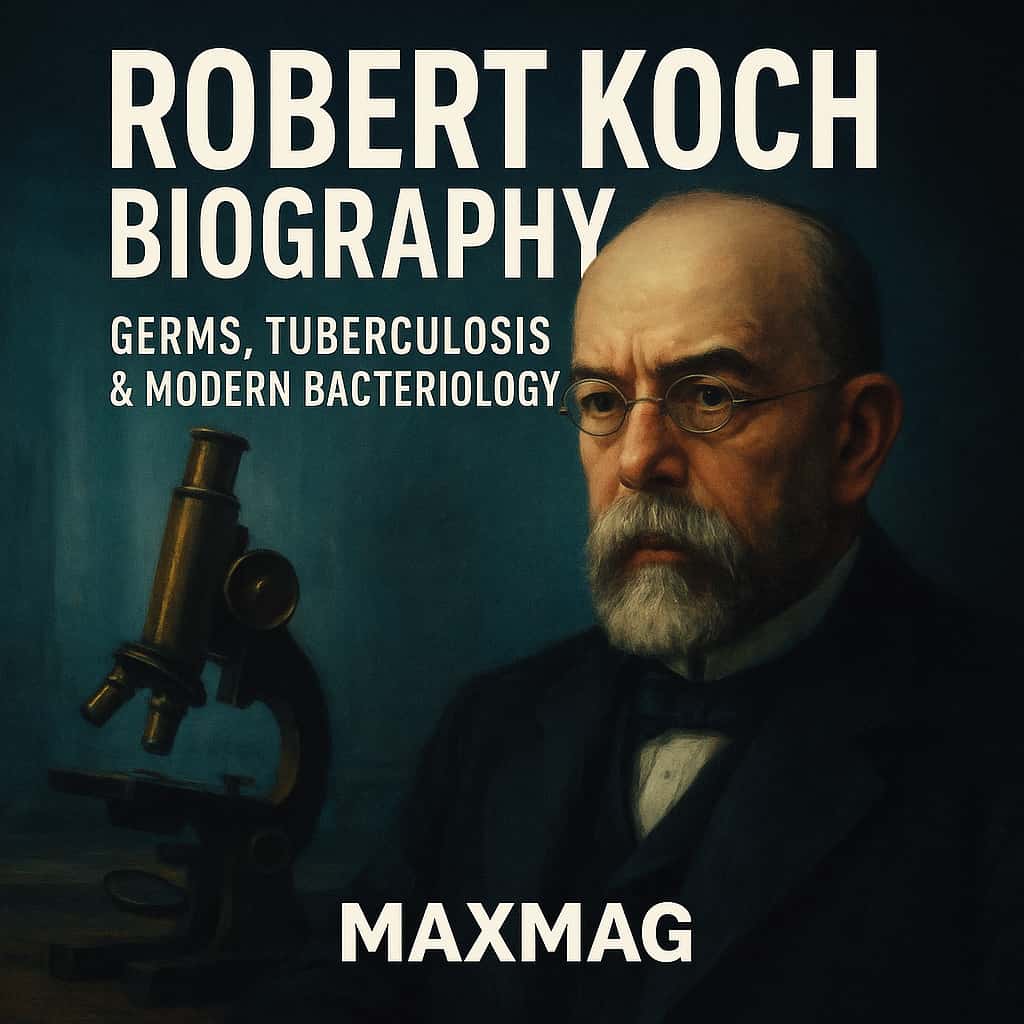

The phrase Robert Koch biography often conjures an image of a stern German doctor staring down a microscope, hunting for invisible killers. It is an accurate picture, but also a surprisingly incomplete one. Behind the laboratory glassware and the famous “Koch’s postulates” was a rural boy who loved nature, a wartime doctor, a tireless traveller, and a man whose discoveries on tuberculosis and cholera transformed the fate of cities and empires. To follow the Robert Koch biography from a mining town in Hanover to the Nobel Prize is to trace the emergence of germ theory itself – and to see how one life helped redraw the map of modern medicine.

In the late nineteenth century, infectious disease was an everyday terror. Tuberculosis killed one in seven people in some European cities; cholera swept through ports like a biblical plague. Most doctors still blamed bad air, moral weakness or vague “miasmas”. Koch set out to prove something far more radical: that specific diseases were caused by specific microbes and could be tracked, cultured and ultimately contained. This is the heart of any serious Robert Koch biography – not just a list of experiments, but the story of how those experiments forced the world to think differently about life, death and responsibility.

Robert Koch at a glance

- Who: Robert Koch, German physician and pioneering microbiologist.

- Era & field: Late 19th–early 20th century; founder of medical bacteriology and germ theory history.

- Headline contributions: Identified the causative agents of anthrax, tuberculosis and cholera; formulated “Koch’s postulates”.

- Why he matters today: His methods underpin modern infection control, public health campaigns and the way we investigate new diseases.

Early Life and Education of Robert Koch

Childhood in a mining town

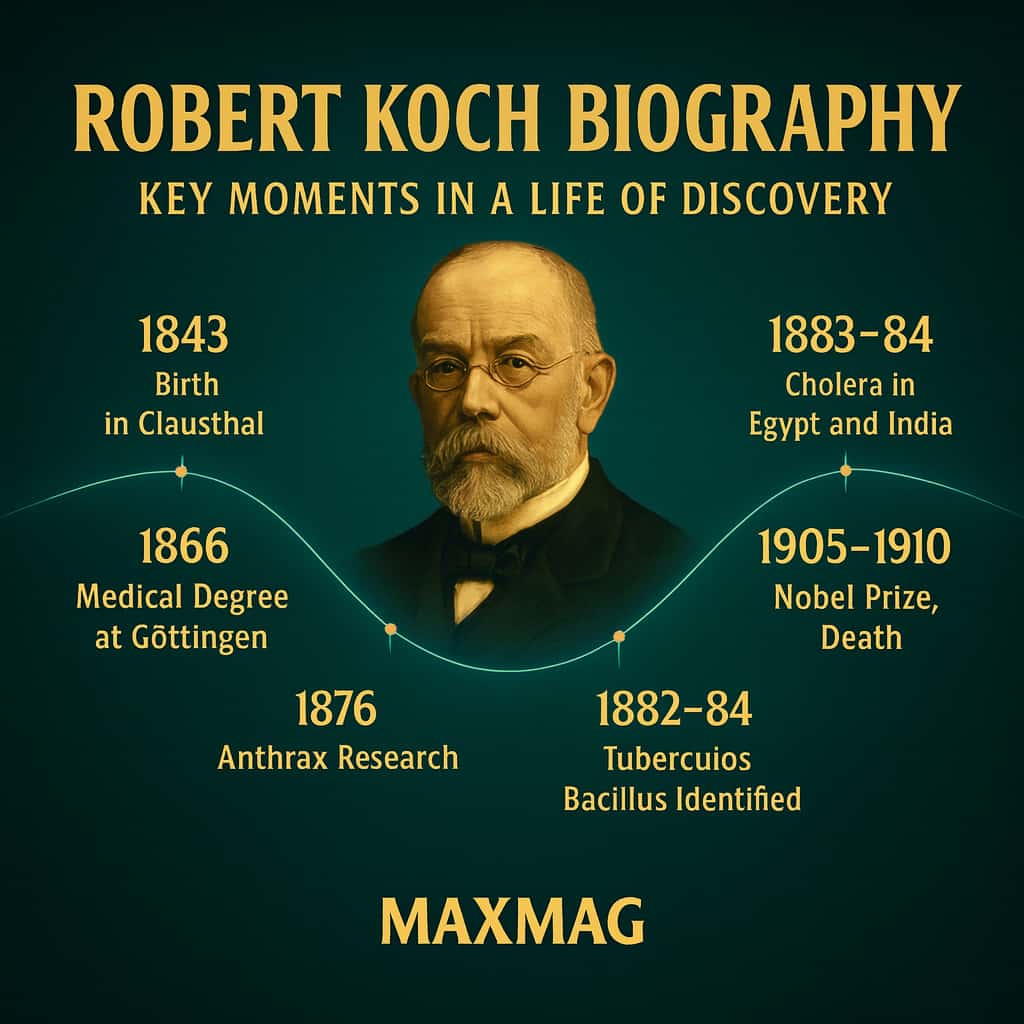

Robert Koch was born in December 1843 in Clausthal, a mining town in the Harz Mountains of what is now Germany. His father worked as a mining official, and the landscape around him was dominated by shafts, smelters and the harsh rhythms of industrial life. Yet the young Koch was drawn as much to the forests and streams as to the machinery. He later recalled collecting plants and insects, a habit that quietly trained his eye to notice tiny details, a skill that would become essential in his work as a microbiology pioneer.

The family was not wealthy, but they valued education. Koch taught himself to read using his father’s newspapers and devoured anything he could find about nature and geography. In a typical Robert Koch biography, this childhood period can look like a prelude, but it was more than that: the mix of industrial discipline and natural curiosity gave him both the patience for repetitive laboratory work and the stubbornness to question accepted wisdom.

University years and intellectual mentors

Koch studied medicine at the University of Göttingen, one of the most respected institutions in the German states. There he encountered Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle, a pathologist who argued that specific “contagium animatum” – living agents – caused specific diseases. Henle’s ideas were still controversial, but they planted a seed. More than a decade before Koch’s famous postulates, the intellectual blueprint for the Robert Koch biography as a germ theory pioneer was being drawn in Henle’s lecture theatre.

As a student, Koch was not a prodigy in the romantic sense. He did not set laboratories ablaze with spectacular early discoveries. Instead, he quietly built a toolkit: dissection skills, careful note-taking, and a respect for method. He also met fellow students who would later become colleagues and critics, forming a network that ran through German medicine at a time when it was becoming the envy of the world.

From hospital wards to rural practice

After completing his degree in 1866, Koch worked briefly in hospitals before taking a position as a district medical officer in the small town of Wöllstein. There, his patients were farmers, labourers and their families. He treated everything from childbirth complications to industrial injuries, often with limited tools and under grim conditions. If the university had given him theory, Wöllstein provided the unvarnished reality of nineteenth-century medicine.

In those years, Koch also married his first wife, Emmy Fraatz, and became a father. The domestic demands of family life ran alongside long days on horseback travelling between villages. Many accounts in any detailed Robert Koch biography note how little free time he had – yet he still carved out hours in the evening to experiment in a makeshift laboratory in his home, tinkering with microscopes and staining techniques long before anyone outside his district knew his name.

By the time he entered his thirties, Koch was no longer just a country doctor. He had quietly equipped himself with the habits and tools that would soon change medical history.

Robert Koch biography and the Birth of Germ Theory

A turning point in the Robert Koch biography: the anthrax breakthrough

The first big break in the Robert Koch biography came not in a famous university clinic but in that improvised home laboratory in Wöllstein. Anthrax was devastating local livestock, ruining farmers and threatening human health. Many still blamed soil poisons or bad air. Koch thought otherwise. He suspected that a specific organism was responsible, and he set out to prove it using nothing more glamorous than a microscope, animal blood, and great patience.

Koch examined the blood of dead animals and saw rod-shaped bacteria. He followed them as they formed spores in the soil and re-infected other animals. Through painstaking experiments, he demonstrated that Bacillus anthracis was not just present in sick animals but could be isolated, grown, and used to cause disease in healthy ones. This was a revelation. It was the first time a specific bacterium had been conclusively tied to a specific disease, a cornerstone of germ theory history.

Germ theory moves from speculation to evidence

Before Koch, figures such as Louis Pasteur had already hinted that microorganisms caused disease, particularly in the context of fermentation and food spoilage. But much of that work was indirect. What made Koch’s anthrax studies so powerful was their simplicity and reproducibility. If a farmer, a government inspector or another scientist followed Koch’s steps, they could see the same organism doing the same deadly work.

This was the moment when the abstract debate about “miasmas” versus germs shifted decisively. The Robert Koch biography cannot be separated from this wider transformation. His meticulous experiments gave governments and health authorities something they had never had before: a clear target. If specific microbes caused disease, then sanitation, vaccination and surveillance could be designed around them. The idea that a doctor could trace a deadly outbreak back to a single organism and laboratory culture was no longer fantasy; it was protocol.

Koch’s postulates and a new standard of proof

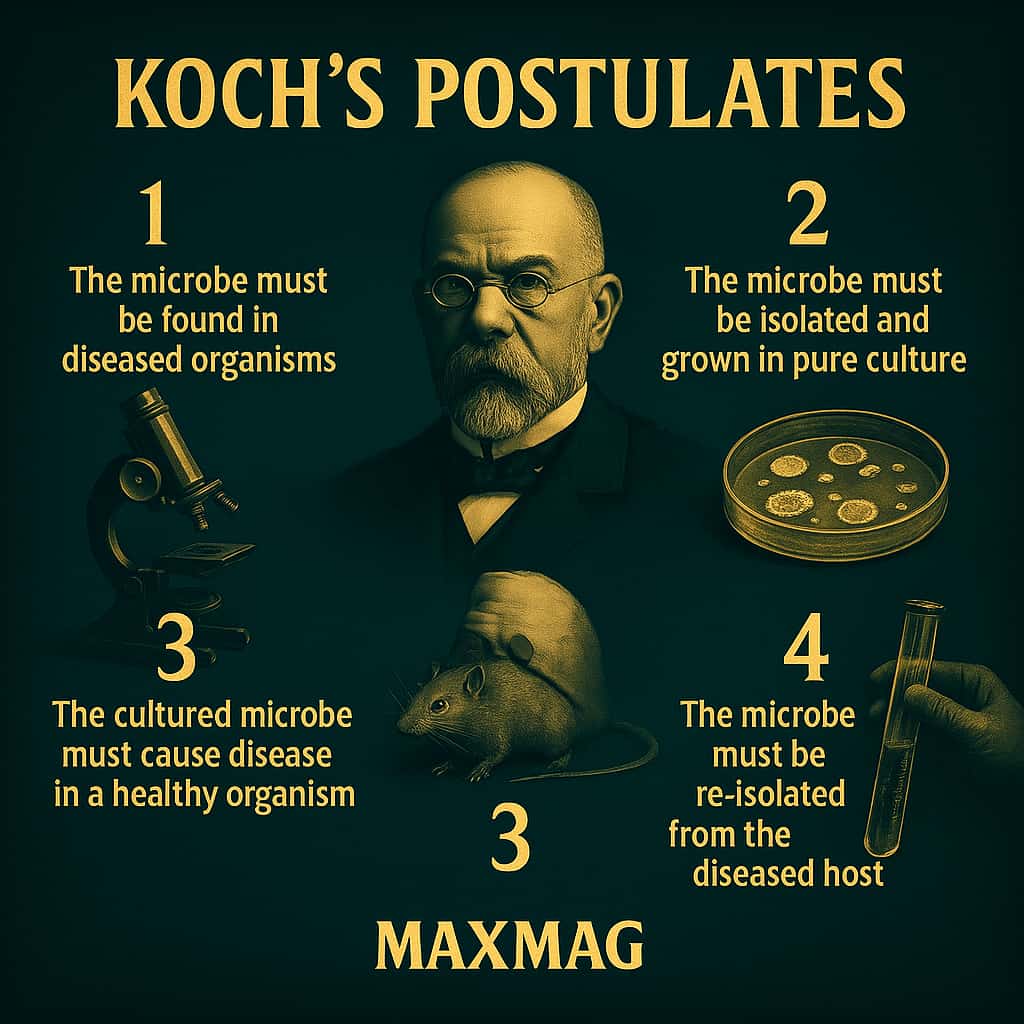

From his work on anthrax, Koch and his collaborators derived what became known as “Koch’s postulates” – criteria for proving that a particular microbe causes a particular disease. In modern textbooks these postulates are often summarised as four neat rules, but in context they were a radical demand for rigour. A microbe had to be found in every case of the disease, isolated in pure culture, cause the disease when introduced into a healthy host, and be recovered again from that host.

For the lay reader, an everyday analogy helps. Imagine suspecting that a particular ingredient in your kitchen is giving you food poisoning. Koch’s logic says: find that ingredient in every bad meal, isolate it in a separate jar, add it deliberately to a test dish, and prove that the dish makes someone ill. Only then can you be sure your suspicion is justified. This approach turned vague blaming of “bad food” or “bad air” into something testable – one reason why any serious Robert Koch biography emphasises these postulates as much as his famous bacteria.

Koch’s postulates did more than settle scientific arguments. They set a standard for how evidence should look whenever someone claimed that a microbe, a chemical or even a lifestyle factor caused disease. That standard still shapes clinical trials and public health decisions today.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Robert Koch

The conquest of tuberculosis

If anthrax made Koch famous among scientists, tuberculosis made him a household name. By the early 1880s, tuberculosis – or “consumption” – was the great white plague of Europe, responsible for more deaths than any other single disease. On 24 March 1882, Koch announced that he had identified the bacillus that caused tuberculosis. He showed stained slides of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to the Berlin Physiological Society, demonstrating how the bacterium could be seen, cultured and traced from patient to patient.

For ordinary people, the impact of this discovery was immense. Tuberculosis had been wrapped in romantic imagery – pale poets, tragic heroines – but in crowded tenements it was simply a slow, painful death. To many readers of a contemporary Robert Koch biography, his identification of the tubercle bacillus felt like naming a long-hidden enemy. It also provided the anchor for campaigns that still continue today, from sanatoriums to World Tuberculosis Day.

Cholera on the move: Egypt, India and the comma bacillus

Barely had Koch settled into his role as the world’s leading tuberculosis expert when he was dispatched abroad. Cholera was ravaging Egypt and later India, and the German government sent him to investigate. In makeshift field laboratories in Alexandria and Calcutta, he dissected victims, examined water sources, and battled local conditions that would have horrified a laboratory-trained bacteriologist.

Koch eventually isolated what he called the “comma bacillus”, now known as Vibrio cholerae, from the intestines of cholera victims and from contaminated water. He showed that the same organism appeared again and again along the pathways of the epidemic, embedding his name not just in the history of tuberculosis discovery but also in the history of cholera etiology. For those tracing the Robert Koch biography as a global story, these expeditions mark a key shift: Koch was no longer just a German physician, but an international authority moving through imperial networks and contested colonial spaces.

Laboratory revolutions: staining, solid media and pure culture

Beyond specific diseases, Koch transformed how laboratories worked. He refined staining techniques, making it easier to distinguish bacteria under the microscope. He and his team developed methods for growing bacteria on solid media such as agar, allowing researchers to separate individual colonies and obtain pure cultures. These might sound like technical footnotes in a Robert Koch biography, but they were revolutionary. They gave bacteriology a visual language – distinct colonies, recognisable shapes, clear differences – and made it possible to compare microbes across laboratories and continents.

To understand their importance, imagine trying to identify different types of seeds in a muddy handful of soil. Koch’s methods were like teaching the world to wash, sort and plant those seeds in separate pots so you could finally see what each one grew into. Without that step, the dramatic victories over diseases like diphtheria, plague and tetanus in later decades would have been impossible.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

The workshop of modern bacteriology

Koch’s Berlin laboratory became a kind of workshop for the new science of bacteriology. Young researchers from across Europe and beyond came to learn his methods: how to pour plates, handle cultures, design animal experiments and interpret results. Many of the names that later appear in any extended discussion of microbiology pioneer history – Paul Ehrlich, Emil von Behring, Shibasaburo Kitasato – passed through these rooms, turning the Robert Koch biography into a networked story rather than a solo performance.

Visitors described a work environment that was both intense and strangely matter-of-fact. Experiments ran late into the night; failures were common. Koch could be brusque, even dismissive, but he expected from others no more than he expected from himself: exact records, clear images and claims that could survive sceptical scrutiny. In this sense, his working style helped define the culture of the laboratory as a place where evidence mattered more than hierarchy.

Rivalry and respect: Koch and Pasteur

No Robert Koch biography is complete without Louis Pasteur. The German physician and the French chemist are often cast as rivals, and there is truth in that portrayal. They worked on similar problems, sometimes criticised each other publicly, and were caught up in the national rivalries of their time, especially in the decades after the Franco-Prussian War.

Yet to reduce their relationship to a feud is to miss something important. Pasteur’s earlier work on fermentation and vaccines paved the way for Koch’s focus on specific bacteria, just as Koch’s methods of isolation and proof strengthened Pasteur’s arguments. Together, their intertwined careers pulled germ theory from the margins into the mainstream of nineteenth-century science and medicine. For modern readers, this part of the Robert Koch biography is a reminder that even towering scientific figures operate within communities, traditions and, yes, rivalries that push them on.

At the intersection of laboratory and policy

Koch spent much of his career as a government advisor on infectious diseases. This aspect of the Robert Koch biography is sometimes overlooked, but it mattered enormously. His reports shaped policies on meat inspection, quarantine and urban sanitation. He served on commissions that investigated outbreaks from Africa to Asia, carrying the tools of the laboratory into the realm of politics and international health.

In our own age of pandemic debates and public briefings, it is easy to see parallels. Koch’s insistence that policy be grounded in laboratory evidence helped establish a model in which public health decisions are expected to rest on data rather than mere opinion – a model that remains contested, but enduring.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

The tuberculin episode: promise and disappointment

Koch’s career was not a straight march of triumphs. In the early 1890s he announced tuberculin, a substance derived from tuberculosis bacteria, which he hoped would cure the disease. Public expectation soared; newspapers hailed a miracle. But clinical results were inconsistent and often poor. Many patients did not improve; some deteriorated. Koch’s reputation took a serious knock, and critics accused him of over-promising.

Modern historians tend to see this episode as a painful but revealing chapter in the Robert Koch biography. Tuberculin turned out to be far more useful as a diagnostic tool than as a therapy, forming the basis of later skin tests for latent infection. The misstep shows Koch as a human scientist: ambitious, fallible, susceptible to the same mixture of hope and pressure that still accompanies experimental treatments today.

Colonial medicine and ethical blind spots

Koch’s work took him into European colonies in Africa and Asia, where he studied diseases such as sleeping sickness. He advocated aggressive campaigns against tsetse flies and experimented with treatments that, by today’s standards, would raise serious ethical concerns. Patients were sometimes exposed to toxic compounds with limited consent or comprehensive follow-up.

A balanced Robert Koch biography cannot ignore these aspects. They highlight how scientific progress was entangled with colonial power, and how the desire to control disease sometimes overshadowed the rights and dignity of people in colonised regions. These episodes are reminders that even groundbreaking science can be compromised when conducted in contexts of deep inequality.

Misunderstanding Koch’s postulates

In popular discussions, Koch’s postulates are sometimes invoked as a rigid checklist and used to question the reality of diseases that do not fit neatly into nineteenth-century models – viruses that cannot be easily cultured, asymptomatic carriers, complex chronic conditions. Yet Koch himself recognised limitations, particularly when he encountered carriers who harboured pathogens without falling ill.

Seen in context, the postulates were tools for a particular moment in microbiology history, not unbreakable laws. A thoughtful Robert Koch biography therefore treats them as a starting point that evolved into more flexible criteria as new technologies and concepts – such as molecular biology and virology – emerged.

Impact on Microbiology and on Wider Society

From laboratory benches to kitchen sinks

The consequences of Koch’s work reached far beyond clinics and laboratories. As germ theory moved into public consciousness, it changed how people cleaned their homes, prepared food and even thought about touch and intimacy. In the United States, the new understanding of germs influenced everything from advertising to architecture, a process documented in historical studies of “the gospel of germs” and explored in depth in Harvard’s overview of germ theory and public health.

By making microbes visible, the Robert Koch biography helped make invisible risks feel manageable. Boiling water, pasteurising milk, washing hands – these became rational acts rooted in scientific evidence rather than vague superstition. The modern obsession with hygiene, for better and worse, owes a great deal to the victories over tuberculosis, cholera and other infections that Koch and his contemporaries helped to secure.

Building the foundations of modern microbiology

In scientific terms, Koch’s influence can be seen in almost every microbiology laboratory today. The practice of isolating organisms in pure culture, classifying them by shape and behaviour, and linking them to specific diseases became standard. His work turned “bacteriology” from a loose set of observations into a coherent discipline with shared methods and expectations.

Students still learn about Koch’s postulates, stain slides in ways that descend from his experiments, and trace lines of mentorship back through researchers who trained in his orbit. In that sense, the Robert Koch biography is not just a story of past breakthroughs; it is embedded in everyday routines whenever a lab technician plates out bacteria or a clinician orders a culture to identify an infection.

Changing the politics of disease

Koch’s discoveries also altered how governments thought about disease. If specific pathogens could be identified and controlled, then failing to do so became a political failing as much as a natural tragedy. Public health departments expanded; cities invested in clean water and sewer systems; international conferences debated quarantine rules and disease reporting.

The idea that states had a duty to protect citizens from infectious disease – an idea that underpins contemporary pandemic responses – is closely linked to the germ theory revolution. In this way, the Robert Koch biography touches on questions of citizenship, responsibility and trust that remain pressing today.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

A reserved yet determined personality

Descriptions of Koch from colleagues and students paint a picture of a reserved man, more comfortable with a microscope than with small talk. He was not a charismatic lecturer in the theatrical sense; his power lay in quiet authority and the quality of his evidence. Yet beneath the calm surface there was steel. The same stubbornness that kept him counting bacteria in animal blood for months on end also made him slow to back down in disputes.

This temperament shaped the Robert Koch biography in subtle ways. It helped him endure years of obscurity in rural practice, and later the intense scrutiny of the international scientific community. It may also have contributed to personal strains, including the eventual breakdown of his first marriage.

Relationships and domestic life

Koch married twice. His first marriage to Emmy Fraatz produced a daughter but grew strained as his career demanded long hours and extended travel. After their divorce, he married the actress Hedwig Freiberg, a much younger woman whose lively social world contrasted sharply with his austere laboratory environment. The age gap and his public status drew comment, adding a personal subplot to the Robert Koch biography that some contemporaries found scandalous and others simply puzzling.

These domestic details matter not because they define his scientific worth, but because they remind us that even “founders of modern bacteriology” lived within the messy constraints of human relationships. Koch juggled obligations to patients, students, governments and family, often imperfectly, just as scientists do today.

Worldview and politics

Koch was not known for strong religious commitments, and he kept his political views mostly private. He often described himself as a man of facts rather than ideology. Yet he lived through a period of intense nationalism and imperial expansion, and his role as a German expert abroad inevitably carried political weight.

For contemporary readers seeking to understand the Robert Koch biography as more than a sequence of laboratory notes, this reserve is striking. It suggests a man who believed that the most important statements he could make were written in bacterial cultures and infection curves rather than in pamphlets or speeches.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Robert Koch

The Nobel Prize and international recognition

In 1905, Koch received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on tuberculosis. By then he was already famous, but the award cemented his status as a global scientific authority. He travelled widely, attended conferences, and advised on health policies from Europe to Asia. For journalists and biographers, the Nobel ceremony offered a satisfying climax to the Robert Koch biography – the rural doctor turned world-renowned scientist.

Yet Koch himself did not treat the prize as a final chapter. He continued to work, study new diseases and refine his ideas until his health began to fail. The Nobel, in his view, recognised not the end of a journey but the potential of methods that still had more to give.

Declining health and final lectures

In his later years, Koch suffered from heart problems. Even so, he remained active, giving lectures and overseeing work at the institute that would eventually bear his name. One of his final public appearances was a lecture on tuberculosis at the Prussian Academy of Sciences, delivered only days before his death in 1910 in Baden-Baden.

There is a poignancy in this image: an ageing scientist speaking about a disease he had helped to expose but that still killed millions. It reminds us that the Robert Koch biography is not a story of simple victory. His discoveries opened doors, but they did not end the struggles against tuberculosis, cholera or other infections. Those battles continue into the twenty-first century, as global health campaigns wrestle with antibiotic resistance, poverty and political instability.

How contemporaries remembered him

Obituaries and memorials after Koch’s death portrayed him as a figure of almost mythic stature – the man who revealed the hidden enemies of humankind. Institutes were named after him, statues erected, biographies commissioned. Yet some contemporaries also noted his flaws: his sometimes harsh judgments of colleagues, his miscalculations around tuberculin, his entanglement with colonial projects.

This duality has persisted. A nuanced Robert Koch biography today honours the scale of his achievements while acknowledging the costs and controversies that came with them. In doing so, it invites us to think about how we remember scientific heroes more broadly – and about the stories we tell ourselves when we say that science “saved” us.

The Lasting Legacy of the Robert Koch biography

Why Robert Koch still matters in the age of pandemics

In recent years, as new pandemics have pushed terms like “reproduction number” and “contact tracing” into everyday conversation, the legacy captured in any careful Robert Koch biography has felt newly relevant. His insistence that diseases have specific causes that can be traced, measured and interrupted underpins everything from modern contact-tracing apps to debates over mask mandates and vaccination strategies.

Journalists and historians have drawn direct lines from the laboratories of Koch and his contemporaries to today’s headlines, including in Washington Post reporting on how germ theory reshaped everyday life and parenting. When public health officials urge basic hygiene or structural reforms, they are unknowingly echoing arguments first sharpened in the era of anthrax, cholera and tuberculosis.

Understanding Robert Koch biography to understand ourselves

Ultimately, the value of revisiting the Robert Koch biography lies not only in celebrating a scientific pioneer but in understanding the world we inhabit. Our expectations that illnesses have identifiable causes, that governments should respond to outbreaks, that laboratories can reveal hidden truths – all of these are products of the germ theory revolution that Koch helped to drive.

His life story forces us to confront difficult questions. How do we balance the urgency of fighting disease with the need to respect individual rights? How do we evaluate bold new treatments without repeating the missteps of tuberculin? And how do we ensure that the benefits of microbiology pioneer work – vaccines, antibiotics, clean water – are shared fairly across a deeply unequal globe?

As we grapple with new pathogens and old inequalities, the Robert Koch biography remains more than a historical curiosity. It is a guide to thinking about responsibility, evidence and hope in an age where the smallest organisms can still upend the largest societies.

Frequently Asked Questions about Robert Koch biography

Q1: Who was Robert Koch and why is the Robert Koch biography so important to medical history?

Q2: What are Koch’s postulates and how do they feature in the Robert Koch biography?

Q3: How did Robert Koch discover the cause of tuberculosis?

Q4: What role did Robert Koch play in understanding cholera?

Q5: Were there any controversies or mistakes in Robert Koch’s career?

Q6: How does the Robert Koch biography connect to public health challenges today?