In the second half of the twentieth century, few writers managed to smuggle such difficult science into everyday conversation as successfully as Richard Dawkins. This Richard Dawkins biography is, in one sense, the story of a mild-mannered Oxford zoologist who became a lightning rod for debates about evolution, religion and reason itself. In another sense, it is the story of how a single book – and the selfish gene at its heart – rewired the way millions of people think about life, purpose and what it means to be human.

Today, Richard Dawkins is one of the most famous evolutionary biologists on the planet, an unexpected public intellectual whose name is as likely to appear in arguments about atheism as in discussions of animal behaviour. But the Richard Dawkins biography is more complex than the caricatures suggest. Behind the sharp soundbites lies a patient observer of nature, a careful writer and an evolutionary pioneer who helped knit together genes, behaviour and culture into a single story about how information spreads through the world. Understanding that journey means going back to a childhood that began far from the lecture halls of Oxford.

Richard Dawkins at a glance:

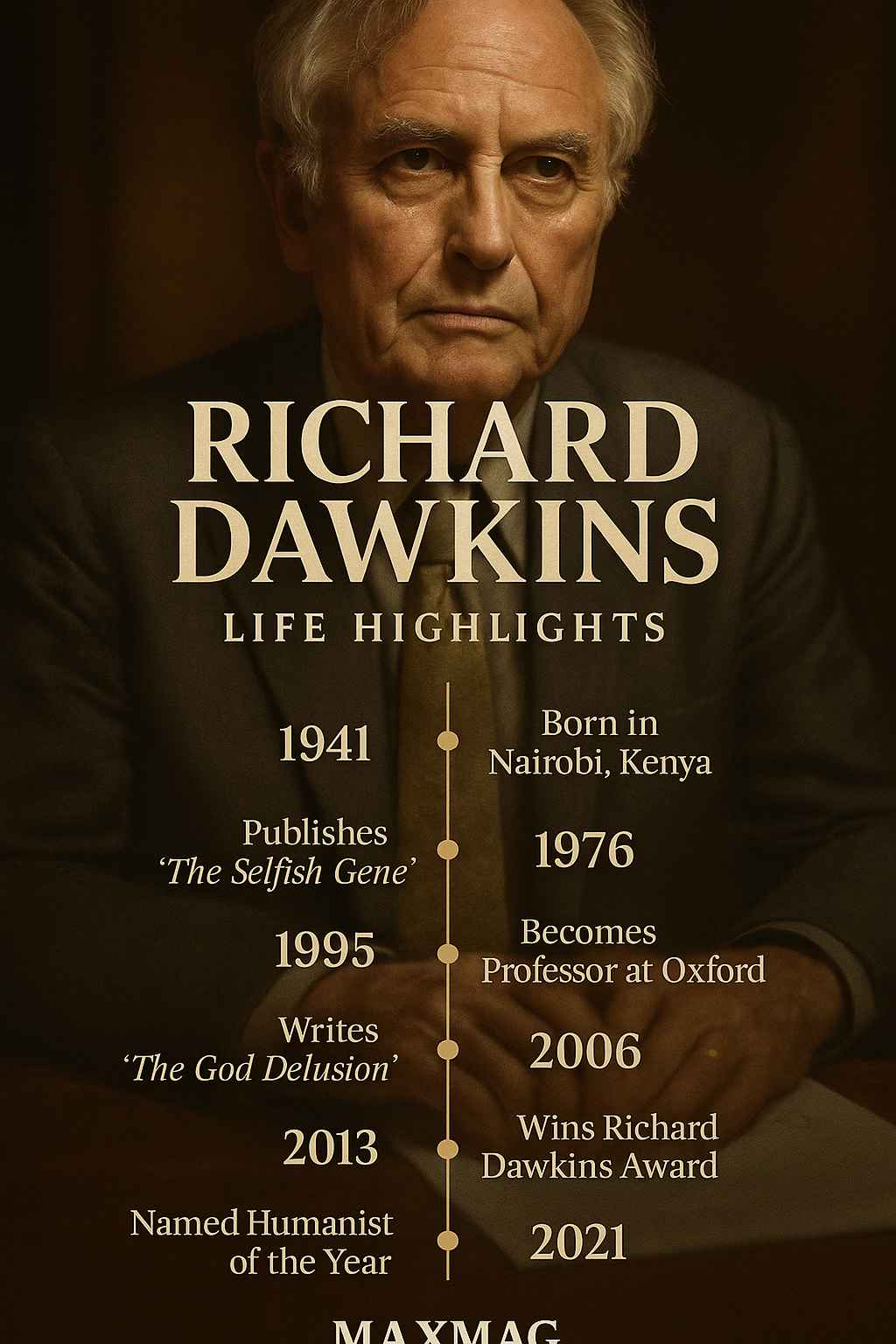

- Born: 1941, Nairobi (then British Kenya); raised mainly in England.

- Field: Evolutionary biology, ethology (the study of animal behaviour), public communication of science.

- Headline contributions: Popularised the “selfish gene” view of evolution; helped introduce the concept of “memes” as units of cultural transmission; became a leading voice in late-20th-century debates on science and religion.

- Why he matters today: His ideas still shape how we talk about genes, altruism, culture and secularism, and his books remain landmarks in modern science writing.

Early Life and Education of Richard Dawkins

Colonial childhood and early curiosity

Any Richard Dawkins biography has to begin in East Africa. Clinton Richard Dawkins was born on 26 March 1941 in Nairobi, where his father, an agricultural civil servant, was stationed during the Second World War. The family’s time in Kenya was short-lived; when the war ended they returned to England, eventually settling on a country estate near Chipping Norton in Oxfordshire. The landscape of fields and woods, with its birds, insects and small mammals, quietly seeded a lifelong fascination with the natural world.

Dawkins has recalled being a fairly conventional, churchgoing child in post-war Britain, accepting the Anglican faith around him in much the same way he accepted English weather and school uniforms. Yet his curiosity about how things worked was already pulling in a different direction. This double track – sentimental attachment to tradition and a mind increasingly loyal to evidence – would become one of the recurring tensions in any Richard Dawkins biography, reappearing later in his clashes with religious authority.

School years and the first cracks in faith

Educated at prestigious English schools, Dawkins was bright but not especially rebellious. What stands out from his recollections is not teenage defiance but a growing discomfort with religious teachings that did not seem to match the scientific accounts he was reading. At around the age of 16, he has said, he stopped believing in God altogether. It was not a dramatic revolt so much as an intellectual shedding of skin. For the young Dawkins, evolution by natural selection, outlined so economically a century earlier in Charles Darwin’s work, offered a far more satisfying explanation for the diversity of life than the stories from scripture.

During these years he discovered a particular talent: taking complicated scientific ideas and stripping them down to their logical bones. Friends and teachers noticed his ability to explain, to persuade, to turn abstract principles into clear narratives. Later, when the “Richard Dawkins biography” became a kind of cultural shorthand for outspoken rationalism, this early talent for lucid explanation would prove crucial. Long before he was a controversial figure, he was a student who simply liked making sense of things.

Oxford and an apprenticeship in evolutionary biology

Dawkins entered the University of Oxford in 1959 to study zoology, at a moment when evolutionary theory was being reshaped by genetics and mathematical modelling. He studied under the celebrated ethologist Nikolaas Tinbergen, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize for his work on animal behaviour. Tinbergen’s approach – carefully observing animals in their natural surroundings, teasing out both the immediate triggers of behaviour and its evolutionary history – deeply influenced Dawkins and is a vital thread in any Richard Dawkins biography.

At Oxford, he learned to think in terms of adaptation: what problems does this trait solve, and how might natural selection have shaped it? This way of looking at the world would soon prove revolutionary when applied not only to bodies but to genes and even ideas. Dawkins completed his undergraduate degree and then stayed on for his doctorate, working on behavioural studies of chicks. Yet even this seemingly narrow work sharpened his attention to decision-making, cost-benefit trade-offs and the idea that animals might be seen as “survival machines” engineered by evolution.

Richard Dawkins biography and the birth of his big ideas

The road to The Selfish Gene

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, evolutionary biology was wrestling with big questions about altruism, cooperation and levels of selection. Why would an animal risk its own life to warn others of a predator, or feed unrelated individuals? Some biologists spoke of “the good of the species”, imagining natural selection acting at a group level. Dawkins thought this muddied the logic. A clear Richard Dawkins biography of ideas has to recognise his main move: he shifted the basic unit of evolutionary explanation from the individual or the group to the gene.

Working through the implications of gene-centred evolution, Dawkins wrote a series of essays for his students. It was his then-wife, the ethologist Marian Stamp Dawkins, and colleagues who encouraged him to turn these into a book. When The Selfish Gene appeared in 1976, it hit like a well-aimed stone thrown into a pond. The book argued that genes are “selfish” replicators, using bodies as vehicles to propagate themselves. This did not mean that organisms are selfish in everyday terms; on the contrary, altruistic behaviour can be explained as genes helping copies of themselves in relatives. But as a way of talking about evolution, it was a sharp break from the softer language of nature’s harmony.

Explaining a radical view in plain language

One reason the “Richard Dawkins biography” became bound up with the wider history of evolutionary thought is that he was exceptionally good at translation – not between languages, but between professional science and lay understanding. The Selfish Gene is full of metaphors and thought experiments: birds playing “hawk” or “dove” strategies, genes “wanting” to get into the next generation, evolutionary “arms races” between predators and prey. At heart, these were ways of describing cold mathematical logic without the equations.

Dawkins did not invent the gene-centred view – it drew on earlier work by W. D. Hamilton, George C. Williams and others – but he gave it a narrative voice. In doing so, he positioned himself as a kind of evolutionary biologist-journalist, telling the story of modern science to a general audience. Any serious Richard Dawkins biography must therefore treat The Selfish Gene not only as a scientific text but as a work of literature that changed how people talk about nature.

The birth of memes and cultural evolution

Tucked away towards the end of The Selfish Gene is a short chapter that would later take on a life of its own. Dawkins suggested that just as genes are units of biological information, there might be units of cultural information that also replicate and evolve. He called these units “memes” – ideas, tunes, habits or technologies that spread from brain to brain. In a Richard Dawkins biography focused on influence, this is a crucial moment: he was stretching Darwinian thinking beyond biology.

The meme concept was speculative and, at the time, almost a side note. Yet it foreshadowed a wave of later work on cultural evolution, network theory and the spread of information in a connected world. Decades later, the word “meme” would escape its original meaning to describe jokes and images circulating online – an ironic twist that placed Dawkins inadvertently at the centre of internet culture. For readers following the Richard Dawkins biography as an intellectual arc, the meme idea shows his willingness to push natural selection into new territories, asking whether the same logic could explain how ideas compete and survive.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Richard Dawkins

The Selfish Gene and the gene-centred revolution

If one book defines the Richard Dawkins biography, it is The Selfish Gene. First published in 1976 and updated in later editions, it gathered together decades of work in population genetics and animal behaviour into a single, compelling picture. By treating the gene as the primary unit of selection, Dawkins offered powerful explanations for phenomena that had puzzled biologists, from sterile worker ants to seemingly self-sacrificing birds. The book also popularised concepts such as “evolutionarily stable strategies”, drawn from game theory, helping readers understand how certain behavioural patterns can resist invasion by alternatives.

The impact went beyond biology. Social scientists, philosophers and even economists seized on the gene-centred worldview, sometimes in ways that made Dawkins uneasy. He repeatedly stressed that describing genes as “selfish” was a metaphor, not a licence for selfish behaviour. Nevertheless, this Richard Dawkins biography of ideas includes the uncomfortable fact that some readers used his work to justify harsh individualism, an outcome he strongly rejected.

The Extended Phenotype and the reach of genes

In 1982, Dawkins published what he considers his most important scientific work: The Extended Phenotype. Where The Selfish Gene was a book for general readers, this one was aimed squarely at fellow biologists. It argued that the effects of a gene are not limited to the body that carries it; they can spill out into the environment and into other organisms. A beaver’s dam, a caddisfly’s case or even a parasite manipulating its host’s behaviour can all be seen as parts of an organism’s “extended phenotype”.

In the longer arc of the Richard Dawkins biography, this book shows him at his most theoretical, pushing the logic of gene-centred evolution to its limits. While it never achieved the popular fame of The Selfish Gene, it has been highly influential in evolutionary biology and remains widely cited. It also illustrates a pattern in his career: alternating between dense, technical contributions and more accessible works designed to bring non-specialists into the conversation.

Public science writing: from The Blind Watchmaker to Climbing Mount Improbable

By the mid-1980s, Dawkins had become one of the world’s most recognisable science writers. The Blind Watchmaker (1986) tackled the argument that complex organs such as the eye could not have evolved by chance. Using vivid metaphors – computer simulations, cumulative selection, the “mount improbable” – he showed how natural selection can build staggering complexity step by small step. In a sense, this was the Richard Dawkins biography crossing over into the broader history of evolution, reaffirming and updating Darwin’s insights for a sceptical age.

Later books such as River Out of Eden and Climbing Mount Improbable continued this theme, weaving narratives that combined personal anecdote with hard science. Dawkins was not merely listing facts; he was building a worldview in which evolution was the central organising principle. Along the way, he became an important evolutionary pioneer of popular communication, influencing a generation of writers and broadcasters who saw in his work a template for how to talk about [modern science] without dumbing it down.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

The ethologist’s eye: behaviour first

Although he is best known as a theorist and essayist, the early stages of the Richard Dawkins biography are those of a hands-on ethologist. His doctoral work involved painstaking experiments on how young animals learn and respond to stimuli. This experience left him with a lasting respect for close observation and for questions framed in terms of survival and reproduction.

In lectures and writings, he often emphasised the value of thinking from the gene’s point of view: imagine copying yourself into the future, and then ask which strategies make that more likely. This mental habit shaped his research and his explanations. He did not see his work as an abstract mathematical game but as a way to make sense of real animal lives in real environments.

Oxford and the culture of argument

Dawkins spent most of his professional life at Oxford, first as a lecturer and reader in zoology, later as the inaugural Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science. The university’s tutorial system – small, intense conversations with students – suited his style. Colleagues describe a man who could argue fiercely about ideas and then cheerfully share a drink afterwards. That mixture of sharp critique and personal civility runs like a thread through the Richard Dawkins biography.

His collaborations were often more intellectual than experimental. He drew heavily on the work of others in population genetics, behavioural ecology and evolutionary game theory, synthesising and popularising rather than generating large data sets himself. For some critics, this made him more of a commentator than a pioneer. For his supporters, it was precisely this role – the clear-voiced synthesiser – that made him so important to evolutionary biology’s public face.

Writing as a scientific instrument

For Dawkins, writing was not a side activity; it was a method of thinking. He has spoken of drafting and redrafting until each sentence snaps into place. That attention to craft is part of why the phrase “Richard Dawkins biography” now evokes not just a list of achievements but a certain style: lucid, uncompromising, occasionally barbed.

He preferred long stretches of uninterrupted time to develop arguments, often retreating from public engagements while working on a book. Yet once a book was published, he threw himself into public debates, interviews and lectures, seeing them as extensions of the same mission: to make the logic of evolution and skeptical inquiry as widely understood as possible.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

The New Atheist storm and a polarised image

No honest Richard Dawkins biography can ignore the period when he became a central figure in the “New Atheist” movement. With the publication of The God Delusion in 2006, Dawkins shifted from primarily explaining evolution to mounting a full-frontal critique of religion. The book argued that belief in a supernatural creator is not only unsupported by evidence but actively harmful in many social and political contexts.

The response was explosive. Supporters hailed him as a long-overdue champion of secularism, finally saying what many scientists and non-believers had felt unable to state so bluntly. Critics accused him of caricaturing religion, ignoring its diversity and depth, and contributing to an atmosphere of culture-war hostility. From this point, for many people outside science, the phrase “Richard Dawkins biography” meant “famous atheist” first and “evolutionary biologist” second.

Misunderstandings about “selfish genes”

Another recurring controversy is more technical but just as persistent. Many readers took the “selfish gene” metaphor to imply that humans are genetically programmed to be selfish, that altruism is an illusion, or that genes somehow have motives. Dawkins has spent decades trying to correct this misunderstanding, insisting that he is using “selfish” in a precise, gene-level sense. Genes that are good at getting themselves copied will spread; they can do this by promoting kindness as well as competition.

This tension between metaphor and literal interpretation is one of the most interesting threads in the Richard Dawkins biography. It raises a broader question about science communication: how do you make abstract ideas vivid without inviting misleading readings? Dawkins has sometimes conceded that if he could rename the book today, he might choose a title less prone to misreading, but he remains convinced that the fundamental logic is sound.

Public statements and social media battles

In later years, Dawkins’ reputation has also been shaped by his presence on social media, where short, provocative messages travel faster than long, careful arguments. Tweets about religion, feminism or social issues have occasionally triggered storms of criticism, with detractors accusing him of insensitivity or oversimplification. Supporters see the same directness that made his science writing compelling; critics see an older intellectual struggling to adapt to new norms of public discourse.

Whatever one’s view, these episodes underline how the Richard Dawkins biography has moved from the relative quiet of laboratory and library into the noisy arena of contemporary culture. They also highlight a paradox: the very clarity and bluntness that made his writing powerful in book form can become combustible when squeezed into 280 characters.

Impact on Evolutionary Biology and on Wider Society

A bridge between professional science and the public

Within evolutionary biology, Dawkins is respected as a sharp thinker and a gifted expositor, even by colleagues who disagree with aspects of his gene-centred approach. His books have helped generations of students, teachers and lay readers grasp concepts that might otherwise have remained locked inside journals and textbooks. University courses across the world have used chapters from The Selfish Gene and The Blind Watchmaker to introduce ideas about natural selection, adaptation and evolutionary game theory.

One way to grasp his impact is to look at how often his work appears in discussions of evolution’s cultural role, from school curriculum debates to court cases over teaching creationism in US classrooms. For those wanting a deeper sense of that landscape, the National Center for Science Education hosts a rich archive on evolution education and its legal history in the United States, showing the contested terrain into which Dawkins’ books landed. In this broader context, the Richard Dawkins biography intersects with the story of how modern societies negotiate the boundaries between scientific explanation and religious belief.

Influence on secularism and public reason

Beyond biology, Dawkins has become emblematic of a certain style of Enlightenment rationalism: confident in science, wary of faith, impatient with what he sees as superstition. For some, he is a hero of free thought, encouraging people to question inherited beliefs and to demand evidence. For others, his combative tone has reinforced stereotypes about scientists as arrogant or dismissive of culture and tradition.

The truth, as usual, is more complex. Many secular activists credit Dawkins with giving them language and courage; many religious readers, even when offended by his arguments, have engaged with evolution and cosmology more deeply as a result. Either way, the Richard Dawkins biography cannot be separated from the late-20th-century history of science and religion, in which he played a starring, if controversial, role.

Shaping how we talk about genes and culture

The language of selfish genes, memes and extended phenotypes has seeped into everyday speech. We talk about “our genetic inheritance” or “viral ideas” with an ease that would have surprised earlier generations. While Dawkins is far from the only source of these metaphors, his books did a great deal to popularise them. This makes the Richard Dawkins biography part of a larger story: how [evolutionary biology] reshaped our sense of identity, responsibility and freedom.

There is a double edge to this influence. On the one hand, understanding ourselves as evolved creatures can foster humility and empathy; on the other, crude forms of genetic thinking have been used to justify inequality or fatalism. Dawkins has repeatedly opposed such distortions, arguing that describing what is does not prescribe what ought to be. Yet he is acutely aware that once ideas are released into the cultural ecosystem, they evolve in ways no single author can control.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

From conventional belief to outspoken atheism

The spiritual journey in a Richard Dawkins biography is straightforward but significant. Raised in a Christian environment, he gradually abandoned belief in God during his teenage years as he became more persuaded by evolutionary explanations. For much of his early career, this unbelief was a private position rather than a public campaign. He saw his main task as explaining biology, not attacking religion.

Over time, however, he grew more convinced that religious doctrines were not just mistaken but socially harmful, especially when they influenced education, public health or politics. The events of 11 September 2001, carried out in the name of extremist religious belief, profoundly affected him. By the time The God Delusion appeared, atheism was central to his public identity. The Richard Dawkins biography had shifted from scientist-communicator to movement figure, with all the baggage that entails.

Relationships, family and the private man

Dawkins has married three times, including to the actress Lalla Ward, known for her role in Doctor Who. The pair met through Douglas Adams, the author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, another writer who blended science, satire and speculation. These connections hint at the broader cultural circle around the Richard Dawkins biography, linking him to Britain’s tradition of witty, intellectually playful storytelling.

Friends describe him as courteous, sometimes shy, with a dry sense of humour and a fondness for classical music. He is an enthusiastic amateur of technology and gadgets, fascinated by how tools extend human capacities – a fitting interest for someone who wrote about extended phenotypes. Yet he has also spoken candidly about loneliness, ageing and the emotional impact of public vilification, reminding us that behind the sharp public persona is a human being with vulnerabilities.

Health, ageing and reflection

In later life, Dawkins suffered a minor stroke, which led to a temporary reduction in his public speaking schedule. The incident prompted a period of reflection about mortality, legacy and the future of science communication. He continued to write, give interviews and appear at events, but with a greater awareness of limits. For readers following the Richard Dawkins biography as an unfolding story, this phase adds a quieter, more introspective chapter to a life often lived in the glare of controversy.

Even so, he has remained engaged with debates about evolution, education and secularism, using pre-recorded talks, interviews and essays to reach audiences. The combination of physical fragility and continuing intellectual energy is a poignant reminder that even the most robust public figures are subject to the same biological constraints they spend their lives analysing.

Later Years and Continuing Chapter of Richard Dawkins

Autobiographical volumes and re-examining a life

In his later years, Dawkins turned the analytical lens on himself. His memoirs, including An Appetite for Wonder and Brief Candle in the Dark, offer an inside view of the Richard Dawkins biography: childhood memories, academic rivalries, letters from readers and the messy backstage of public life. They reveal a man who is both proud of his achievements and acutely aware of how he is perceived.

These books are also love letters to science as a way of seeing the world. He writes with particular warmth about teachers and colleagues who nurtured his curiosity, about the thrill of discovering that a simple equation can explain an intricate pattern in nature. For readers, they provide a richer, more nuanced portrait than either his admirers or his detractors usually offer.

The digital age and changing audiences

As the media landscape shifted from broadcast television and print to YouTube, podcasts and social media, Dawkins adapted with mixed feelings. He has appeared on numerous programmes, debates and online platforms, trying to use new formats to spread old commitments: evidence, clarity, scepticism. Clips of his debates with religious leaders and commentators have circulated widely, sometimes shorn of nuance.

In this phase of the Richard Dawkins biography, the challenge has been to maintain depth in an environment that rewards speed and outrage. Some of his most thoughtful contributions are long-form interviews and lectures where he can develop arguments without interruption. For those wanting a sense of how the wider media has tracked his impact, major outlets such as The New York Times’ coverage of his work and its critics capture both the enthusiasm and the unease that greet his interventions.

Ongoing debates and unfinished questions

Dawkins remains a figure around whom debates swirl: about free speech on campus, about how scientists should engage with politics, about whether harsh criticism of religion helps or harms the cause of secularism. He has at times found himself at odds with younger activists who share his commitment to evidence but differ on questions of tone, strategy or social justice.

These tensions are part of what makes the Richard Dawkins biography a useful lens on our era. It shows how a scientist can become entangled in cultural battles far beyond the original scope of their research, and how reputations evolve alongside the societies that judge them.

The Lasting Legacy of Richard Dawkins biography

Changing how we see evolution

The most enduring legacy of the Richard Dawkins biography lies in the clarity it brought to evolution. Millions of readers, including many who never studied biology formally, now think of natural selection in terms of genes competing for representation in future generations. They picture arms races between predators and prey, or cooperation seen as a strategy for genetic success. Even critics of the gene-centred view must engage with Dawkins’ arguments, if only to refine or challenge them.

In classrooms, documentaries and popular culture, his metaphors have become part of the standard toolkit for explaining evolution. When a teacher likens DNA to a text, or a journalist talks about “selfish genes”, they are drawing on a narrative architecture that this Richard Dawkins biography has traced back through decades of books and lectures.

Memes, minds and cultural evolution

The meme idea, while controversial, has opened fruitful questions about how culture changes over time. Are religions, political ideologies or artistic styles best understood as memeplexes – bundles of ideas that reinforce each other – competing for human attention? How does digital technology speed up or distort this process? Scholars disagree on the usefulness of strict “memetics”, but the broader conversation about cultural evolution has grown richer in the wake of Dawkins’ provocation.

Here again, the Richard Dawkins biography intersects with the wider history of ideas. By treating culture as something that can evolve according to rules analogous to genetics, he nudged both scientists and humanities scholars to think differently about transmission, inheritance and change.

Science, meaning and the modern search for answers

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Dawkins’ legacy is his insistence that science not only explains how the world works but can also satisfy many of the human longings traditionally addressed by religion. Where others speak of “non-overlapping magisteria” – separate realms for science and faith – he sees a conflict between evidence-based inquiry and dogma. Whether one agrees or not, the Richard Dawkins biography forces a confrontation with hard questions: Where do we find meaning in a universe without a guiding hand? How do we balance respect for tradition with the demands of honest doubt?

In the end, this Richard Dawkins biography offers not a verdict but a map. It traces the journey of a Kenyan-born English boy who fell in love with nature, honed his thinking in one of the world’s great universities, and then carried evolution’s message onto a global stage. His books, arguments and controversies have left strong impressions, both inspiring and infuriating. To understand the Richard Dawkins biography is to grapple with the power of ideas – genetic and cultural – to shape lives far beyond the individuals who first articulate them.

Frequently Asked Questions about Richard Dawkins biography

Q1: What is the central idea of the Richard Dawkins biography in terms of his scientific work?

Q2: Why is The Selfish Gene so important in the Richard Dawkins biography?

Q3: How does this Richard Dawkins biography address his role in the New Atheist movement?

Q4: What are some common misconceptions highlighted in the Richard Dawkins biography?

Q5: How has Richard Dawkins influenced public understanding of evolution?

Q6: What does the Richard Dawkins biography suggest about his long-term legacy?