Rachel Carson did not set out to become a political lightning rod. She was a biologist with a poet’s ear, trained to watch tides and birds, to follow small facts to large truths. Her gift was translation—turning technical observation into public understanding—and she used it to change how millions think about the living world. When she published Silent Spring in 1962, the book did more than challenge a chemical orthodoxy; it rewired civic expectations for scientific honesty, public health, and responsibility.

Writing about Carson in a strictly historical key misses what journalists prize most: context, consequence, and character. This is a story about how evidence travels, how institutions respond, and how one steady voice stitches facts into a narrative wide enough for farmers, parents, lawmakers, and schoolchildren. It is also a story of timing. Postwar America trusted lab coats and miracle products; Carson asked the country to widen its definition of progress. That she succeeded, despite organized pushback and her own failing health, remains one of the most consequential moments in American science communication.

This feature traces her formation as a writer of the sea, the publishing storm around Silent Spring, the policy aftershocks that followed, and the ways her method still shapes decisions about water, wildlife, and human health. Along the way, we consider what her work teaches today’s readers about proportional risk, cumulative effects, and the power of clear prose—habits that define the Rachel Carson environmental legacy.

Defining the Rachel Carson environmental legacy: from sea edges to suburbia

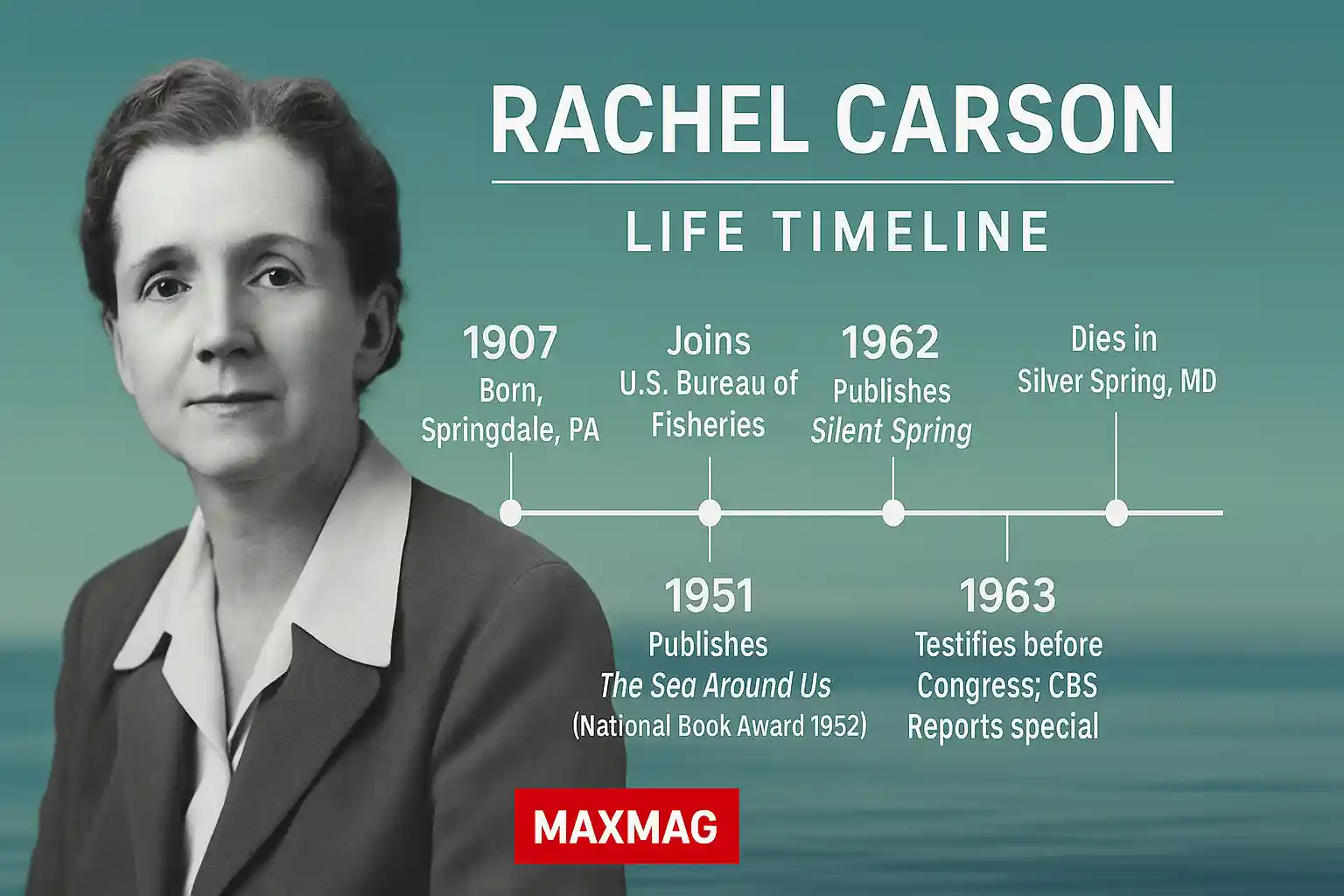

Long before hearings and headlines, Carson spent years explaining how coasts breathe, how plankton blooms rise and fade, and how shorebirds time their routes to the pulse of tide and light. Her early books—Under the Sea-Wind (1941), The Sea Around Us (1951), and The Edge of the Sea (1955)—built a readership that trusted her to be both lyrical and exact. She taught readers to see systems: not a lone gull but a food web; not a beach but a boundary where nutrients, weather, and geology bargain with life.

That perspective became the operating system of the Rachel Carson environmental legacy. Start with natural history, identify the connections, then ask what our choices disturb. This is why Silent Spring landed with such force. By the time Carson interrogated postwar pesticide habits, she had already trained audiences to think like field ecologists. They could follow a chemical plume from a truck to a hedgerow to soil invertebrates to robins and hawks—and, because food chains ignore politics, back to human bodies.

How science writing shaped the Rachel Carson environmental legacy

Carson wrote like a good reporter: observe closely, verify patiently, and explain without condescension. She fused the rigor of a lab memo with the cadence of narrative nonfiction, giving general readers the confidence to follow complex chains of cause and effect. When she raised alarms, they were sourced—field notes, literature reviews, interviews with researchers and physicians, and the lived testimony of affected communities. This discipline made her a difficult target for caricature. Critics could disagree with her conclusions, but they had to reckon with her method.

Journalistically, her most durable innovation was to put processes at center stage. Instead of framing pesticides as villains in isolation, she asked what happens when persistence, bioaccumulation, and synergy share a map. That frame is now routine in environmental reporting, public health, and risk assessment—and it is part of why the Rachel Carson environmental legacy remains a live wire in policy debates.

Why the Rachel Carson environmental legacy still guides policy and culture

Policy rarely changes because of a single book. But landmark journalism can move public sentiment enough to make new institutions imaginable. In the United States, the cascade of citizen pressure, lawsuits, and legislative bargaining in the late 1960s culminated in a new federal framework for environmental protection. For a concise overview of that shift, the Environmental Protection Agency’s own historical summary explains how early-1970s reforms consolidated federal responsibilities and raised standards for testing and disclosure (EPA history of its origins). Carson’s voice was not the only force in that story, but it was catalytic.

The significance for journalism is clear: sustained reporting, amplified by citizen groups and expert testimony, can widen the policy aperture. It is not a matter of sensationalism but of making relationships visible—how a decision made on a loading dock or a farm road can echo through a river, a neighborhood, a clinic, and a courtroom.

Teaching with the Rachel Carson environmental legacy

Classrooms remain one of the easiest places to see Carson’s influence. A teacher might pair a reading from The Sea Around Us with a local stream survey, then ask students to brief a parks board about shade trees, buffers, and pesticide choices near playfields. The exercise builds civic muscles: observing, quantifying, writing for non-experts, and speaking to decision-makers. Over time, those muscles create voters who ask better questions—and professionals who expect to answer them with evidence. In that sense, the Rachel Carson environmental legacy is less a memorial than a method.

Debates around the Rachel Carson environmental legacy

Healthy disagreement followed Silent Spring and continues today. Vector control remains vital in many regions; so do crop protections that prevent catastrophic losses. Carson’s contribution was not a commandment but a frame: look at the entire system, measure consequences over time, and avoid tools that leave a toxic inheritance. For journalists, that frame blocks two lazy extremes—alarmism and complacency—while keeping focus on trade-offs in the real world.

Before the storm: a writer of the sea

Carson kept a scientist’s notebook and a novelist’s patience. She took pains to make the ocean’s machinery comprehensible without shrinking its wonder. Her reporting made it normal for a Sunday reader to grasp how currents carry larvae hundreds of miles, or how a rocky intertidal is as structured as a city block. That baseline literacy mattered when she later traced the street-by-street travel of chlorinated hydrocarbons into soils, streams, and songbirds.

The Rachel Carson environmental legacy is inseparable from this craft. By making systems legible, she prepared the public to weigh trade-offs. Readers learned to ask what a quick fix might cost a watershed, a farm, or a child’s morning outside. That kind of question changes policy because it changes voters—and because it changes professionals who answer to them.

Pushback, caricature, and the discipline of accuracy

No serious story about Carson can omit the counter-campaign. Chemical manufacturers funded critiques, attacked her credentials, and framed caution as hysteria. Some arguments were fair—they asked for clearer data and worried about unintended consequences of regulation. Others were smears, misrepresenting her as an absolutist or ignoring the mounting field evidence she cited. Journalists covering those years learned a lesson that still applies: when an issue touches profit and policy, precision is a moral duty.

The Rachel Carson environmental legacy survived because Carson wrote with care and acknowledged uncertainty where it existed. She did not demand purity; she demanded proportion. Her standard—prove safety across whole systems, not in a narrow test tube—remains a rigorous benchmark for public debate.

A reporter’s checklist for environmental claims

Carson’s pages read like a pre-digital checklist for responsible coverage: start with natural history; map the pathways; track time; verify across silos; and test policy against lived experience. These habits are not nostalgic; they are contemporary practice in good newsrooms and good agencies. They are also the everyday grammar of the Rachel Carson environmental legacy as it shows up in city councils, farm co-ops, and classrooms.

Today’s frontiers: climate signals, biodiversity loss, and public health

Carson did not write in the language of climate modeling, but her method is built for it. When heat, air chemistry, ocean currents, and land use interact, tunnel vision fails. Reporters now follow stories that braid meteorology, epidemiology, and economics, showing how a hotter city can raise hospital admissions, reduce worker productivity, and stress urban wildlife in the same season. The continuity with Carson is not the topic; it is the discipline of tracing pathways.

The same holds for biodiversity. Insect declines change pollination and food webs. Habitat fragmentation alters disease dynamics. These aren’t bullet-point problems; they are system stories, and they reward the kind of careful public writing that built the Rachel Carson environmental legacy in the first place.

The person behind the pages

Carson’s public calm hid private strain. She supported family, fought illness, and endured sexist doubts about whether a woman could credibly analyze chemistry and policy. Yet she kept faith with readers. She assumed that citizens could handle complexity and that officials should be held to the same standard. That respect still reads on the page—and it still recruits new readers into caring about the places they live.

Working rules for the next fifty years

What would Carson ask of us now? A short list emerges from her pages and her practice: respect baselines; follow the route; measure mixtures; center the affected; and keep prose clear. These aren’t slogans. They are the working grammar of the Rachel Carson environmental legacy applied to contemporary problems—from PFAS in drinking water to microplastics in food webs.

What changed, and what did not

Laws were written, agencies stood up, and some practices ended. But the temptations that worried Carson—magical fixes, narrow tests, and the habit of treating nature as a sink—remain. The good news for journalists and readers is that the tools she popularized also remain: field observation, cross-disciplinary reporting, and an insistence on long-term effects. Those tools keep a democracy honest about what it is doing to the places that sustain it.

Case studies: what the data showed, and what it missed

Carson’s argument gained traction because it rested on narratives the public could verify. Birders reported thinned eggshells and nest failures; anglers described streams gone quiet in the weeks after roadside sprays; doctors traced unusual patterns in farm communities. She turned these observations into stories that tied lay testimony to lab results, a move that is now standard in enterprise reporting.

Consider the bald eagle, peregrine falcon, and brown pelican—species whose rebounds later became potent symbols of recovery. The chain of evidence from organochlorines to eggshell thinning and reproductive collapse was built over years and contested at every step. Carson did not claim to have all the answers in 1962; she insisted that the questions were legitimate and urgent. That insistence is a through-line in the Rachel Carson environmental legacy: respect field clues, then push for the studies that can prove or disprove them.

Public health and mosquitoes: nuance over noise

Any journalist covering pesticides will meet the mosquito question. Vector-borne disease control saves lives, and in emergencies officials may choose aggressive tools. Carson understood that. What she objected to was the habit of treating every season like an emergency and every landscape like a blank slate. Her reporting suggested a more layered approach—monitoring, targeted applications, habitat management, and public education—so that communities could reduce risk without writing a blank check to chemicals that lingered far beyond their point of use.

It is here that the Rachel Carson environmental legacy is most often misread. She was not arguing for paralysis but for proportion, for matching tools to context and for weighing collateral damage honestly.

Notebooks, sources, and the craft behind the pages

Great nonfiction rarely shows its scaffolding, but Carson’s scaffolding was meticulous. Her files contained correspondence with researchers, monitoring data from state and federal offices, and the kind of field details—dates, weather, locations—that make a story audit-ready. She interviewed practitioners who would otherwise be pitted against one another in a talk-show frame: farmers and wildlife officers, public health nurses and anglers. Good journalism builds unlikely conversations; Carson did that before it was a newsroom cliché.

One institutional thread matters here. Carson’s career in federal service gave her an insider’s view of how science moves through agencies and where it stalls. For readers who want a concise biographical overview, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service maintains a profile that situates her government work within her writing life (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service profile of Rachel Carson). That context helps explain how the Rachel Carson environmental legacy bridged field observation, agency reports, and public argument.

Global ripples and the long view

Although Carson wrote from U.S. shores, the processes she described were never parochial. Persistent chemicals cross borders by wind and water; migratory species carry exposures between continents. As other nations built environmental ministries in the 1970s and 1980s, many absorbed the lesson that risk assessments must track movement and mixtures, not just immediate toxicity. The journalism that followed repeated Carson’s playbook: start with local evidence, follow the pathways outward, and find the people whose lives register the change first.

In practice, this meant stories that begin with a marsh or a farm can end at a customs warehouse or a trade negotiation. The Rachel Carson environmental legacy operates at that scale because ecosystems do.

Myths, misreadings, and the record

Carson’s critics often argue from extremes. One myth holds that she single-handedly outlawed useful tools; another claims she ignored disease risks. The record shows the opposite: she asked for careful testing, transparency, and context-sensitive use. Her reporting warned against false binaries—technology versus nature, economy versus health—and pressed for solutions that take time seriously. That is why the Rachel Carson environmental legacy still resonates in courtrooms and classrooms alike.

How to report your town’s pesticide story now

Start with the map. Where are applications happening and when? Who decides the timing and dosage, and what data inform those choices? What monitoring exists for off-target drift, water contamination, or non-target species? Which clinics see seasonal spikes in symptoms that might correlate with applications, and what would it take to rule correlations in or out? Talk to people who keep long records—gardeners, custodians, coaches, beekeepers, utility crews. They will know patterns that a single season cannot reveal.

Above all, build stories that link scales. A schoolyard spray can be part of a county contract; a county contract can be shaped by a state list; a state list can be influenced by federal policy. The Rachel Carson environmental legacy is, at heart, a reminder that democratic oversight only works when citizens can see those ladders clearly.

A day in the field: how observation becomes argument

Imagine the kind of reporting day Carson preferred. It begins before sunrise with a tide chart and a thermos. At a marsh edge, you note wind direction, cloud cover, the hour of the tide, the insect noise that rises and falls like breathing. You list birds by call because light is poor; you sketch the shape of a creek mouth because photographs flatten what matters—the shallow bars, the cutbanks, the places where algae catches and slows. Mid-morning you meet a shellfisher hauling gear; by noon you are at a culvert upstream, measuring, not because numbers are magic but because they let strangers follow your steps.

In the afternoon you keep appointments with people who hold different pieces of the same story: a school custodian who knows when grounds crews spray and which classrooms complain about dizziness; a beekeeper who logs hive weights and losses; a county buyer who can explain how products make the list and how contractors win. Late in the day you bring those threads to a biologist who can translate what you have seen into hypotheses—not answers, not yet, but questions with shape. Your notes already look like a map. By evening, you draft a structure for the story, matching claims to evidence, holes to sources, and alternatives to the people who can test them. That’s the practical heartbeat of the Rachel Carson environmental legacy.

Data, uncertainty, and the ethics of precaution

Carson’s critics often accused her of elevating fear above fact. The charge misses her actual standard: when plausible harm is large and durable, demand stronger proof of safety before deployment. That is not an argument against innovation; it is an argument for keeping the burden of proof where it belongs. Journalists translate that ethic by reporting what is known, what is contested, and what the stakes are if the contested points tilt one way or another.

In practice, that means spelling out confidence levels, sampling limitations, and the difference between correlation and causation without scolding readers. It means asking agencies to release raw monitoring data and methods, not just summaries. It means following up months later, after the cameras leave, to see whether promised studies were done and whether they support the earlier claims. The work is unglamorous, but it is how communities avoid inheriting problems they cannot easily reverse—and how the Rachel Carson environmental legacy translates into durable public trust.

Language and metaphor: sentences that carry systems

Carson’s prose is often praised for its beauty, but the praise can be vague. What her sentences actually do is carry structure. She uses metaphor to make relationships visible: soil as a community, a coastline as a living hinge between realms, a stream as a ledger that records what a town forgets. The effect is not decorative; it is cognitive. Readers who might bounce off a data table can still follow how a compound moves from spray to leaf to worm to robin to hawk—and why time matters as much as dose.

For journalism, there is a lesson here about precision without sterility. A vivid line can earn a careful paragraph that follows; a careful paragraph can earn reader attention for the graph or map that seals the argument. Carson’s pages alternate between these modes, braiding image and mechanism until readers feel oriented in a world that would otherwise seem abstract. In a century that rewards distraction, that braid is an editorial advantage and a signature of the Rachel Carson environmental legacy.

Inside the publishing storm: how a book became a national conversation

When Silent Spring began running in magazine excerpts, the reaction was immediate. Editors fielded letters from gardeners and chemists, schoolteachers and spray contractors. Carson’s publisher braced for legal threats, and reporters sifted through press packets from industry groups that attempted to pre-empt the book’s claims. The debate unfolded in a sequence familiar to any newsroom: assertion, counter-assertion, document dump, expert interviews, and—crucially—follow-up reporting that tested talking points against field conditions.

Carson stayed mostly out of the theater and in the facts. She trusted that evidence laid out patiently could withstand volume. Her media strategy, such as it was, relied on earned credibility. That choice paid off; public trust grew where her opponents tried to substitute stamina for proof.

Farmers, livelihoods, and the search for better pest management

Carson never caricatured growers as villains. She understood the basic arithmetic of agriculture: pests eat margins, and margins are often thin. Her objection was to tools that solved a short-term problem by creating larger, slower harms—resistance in target species, collapse of natural predators, residues that traveled into water and wildlife. She highlighted integrated approaches—crop rotation, biological controls, selective applications—that kept yields viable without mortgaging the landscape. That pragmatic balance is one reason the Rachel Carson environmental legacy continues to win allies among practitioners.

Modern echoes: PFAS, neonics, and the systems we are still learning to see

Today’s chemical debates feature new acronyms but the same narrative architecture. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) raise questions about persistence and mobility in water; neonicotinoid insecticides raise questions about pollinators and food webs. The reporting challenges would be familiar to Carson: track pathways, measure mixtures, and make long-term effects legible to people who vote, shop, and parent. In other words, practice the habits that built the Rachel Carson environmental legacy and keep adapting them to new evidence.

What editors can learn from Carson’s pages

Assign the system, not just the scene. If a neighborhood complains about a spray program, send one reporter to the contract meeting and another to the creek. Pair a data journalist with a photographer who can make the invisible visible—a ditch that flows to a playground, a culvert that jumps a property line. Build a running file of documents that readers can search: permits, monitoring results, procurement letters, safety data sheets. Make your newsroom the place where fragments become a public record that anyone can examine. That is an editorial expression of the Rachel Carson environmental legacy.

Conclusion: a clear voice, and a standard for our time

Rachel Carson’s achievement was not to end debate but to raise its standards. She taught readers to follow pathways, to respect uncertainty without surrendering to it, and to treat clarity as an ethical duty. Her books endure because they are disciplined acts of attention, patient enough to be trusted and urgent enough to matter. In a noisy century, that discipline is a civic gift.

The Rachel Carson environmental legacy will keep evolving as new chemicals, new tools, and new economies test our resolve. But the measure Carson offered—evidence presented in human terms, decisions tested against whole systems—remains sturdy. It is a standard any newsroom, agency, farm, or neighborhood can adopt. And it begins, as her pages do, with the humility to ask what our choices sound like in spring.

Letters, friendship, and the private fuel behind public courage

Behind the composed public voice was a woman who relied on friendship, particularly her long correspondence with Dorothy Freeman. Those letters chart the energy and doubt behind a historic book: drafts that would not cohere, days when illness left her exhausted, and the small field moments that refilled the well—a migrating flock threading a coastal sky, a night tide gilded by plankton. Read as a whole, they show a professional who refused to burn out by rage alone. She returned, again and again, to attention and gratitude, the quiet practices that power the Rachel Carson environmental legacy.

Serializations, edits, and the newsroom battles that shaped a movement

Carson’s chapters did not simply leap from desk to bookstore; they were pared, paced, and positioned for maximum public legibility. Editors argued the order of episodes, lawyers vetted phrasing, and fact-checkers pressed for additional sourcing. These frictions improved the work. They are a reminder that movements are not only born of inspiration but of editorial craft—of people who know how to place a new idea where the public can receive it. That editorial workmanship is part of the Rachel Carson environmental legacy too, and it offers a template for journalists taking on complex, contested topics today.

Maine, field notes, and the habit of place

Carson never treated “nature” as a backdrop. Her summers on the Maine coast, wanders along the Chesapeake, and long, quiet field days turned places into teachers. She learned the names of coves and creeks and the moods of weather that worked their edges. That intimacy with place kept her reporting concrete: not abstractions about “the environment,” but particulars—a culvert that runs after storms, a roosting tree that fails after a spray. The habit of place turns readers into witnesses, and witnesses into participants. It is the most local face of the Rachel Carson environmental legacy, and it travels well to any town with a stream, a schoolyard, or a patch of soil.