On a September afternoon in 1969, inside Exeter Cathedral, a celebrated scientist stood at the lectern to address Britain’s scientific elite. Moments into the ceremony, he collapsed with a massive stroke. The man was Sir Peter Medawar, already a Nobel laureate and widely regarded as the father of transplantation. The drama of that moment, coming at the height of his influence, encapsulates much of the tension running through any serious Peter Medawar biography: audacious scientific breakthroughs, public honour and private fragility, allied to an almost mischievous determination to probe the limits of science itself.

For readers curious about how medicine learned to move organs from one body to another, and about the personality behind that leap, a rich Peter Medawar biography is not just a catalogue of prizes. It is the story of a Brazilian-born, Lebanese–British zoologist who turned wartime wounds into questions about why the body rejects grafts, and who then helped build the theory of immunological tolerance that made modern organ transplantation possible. It is also the story of a gifted essayist who asked whether “the scientific paper is a fraud”, and of a man who kept writing after paralysis, dictating books that still shape how young scientists think about their craft.

Peter Medawar at a glance

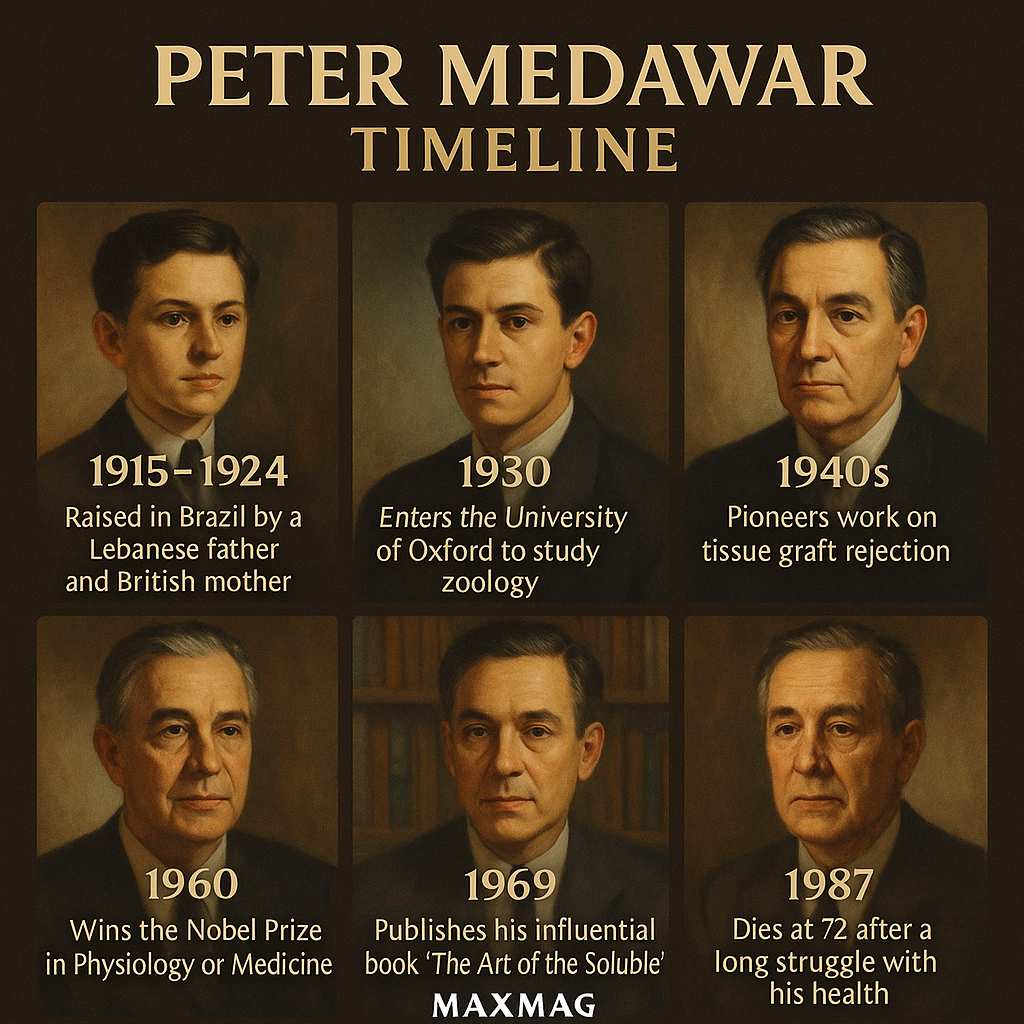

- Brazilian-born British zoologist and immunology pioneer, born in 1915 and raised between Rio de Janeiro and England.

- Co-discoverer of acquired immunological tolerance, a foundation of organ and tissue transplantation.

- Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1960, shared with Frank Macfarlane Burnet, and often described as the “father of transplantation”.

- Brilliant science writer and Reith Lecturer, author of influential books such as The Art of the Soluble and Advice to a Young Scientist.

- Struck by a disabling stroke in 1969 yet continued to write, lecture and mentor, leaving a deep Peter Medawar biography legacy across both medicine and scientific culture.

Early Life and Education of Peter Medawar

A Brazilian beginning in a British–Lebanese family

Any serious Peter Medawar biography must start far from the London laboratories that would later bear his name. Peter Brian Medawar was born in Petrópolis, near Rio de Janeiro, in 1915. His father was a Lebanese Maronite who had become a British citizen, his mother an Englishwoman; the family lived a quietly cosmopolitan life in Brazil, where Peter’s first language was Portuguese and his playgrounds included the still-polluted sands of Copacabana. As he later recalled, the city’s open sewers and the ever-present threat of polio were part of the backdrop of his childhood; one of his brothers was left crippled by the disease.

Music and books were early obsessions. The boy who would one day write sparkling essays about science first fell in love with the gramophone, saving his pocket money to buy opera records and conducting imaginary orchestras in front of a mirror. Opera and literature, not microscopes, formed the emotional soil of the young immunology pioneer. Later in life, when colleagues praised his prose, they were paying indirect tribute to those hours spent listening to Wagner on a crackling disc player in Brazil.

Oxford, mentors and the making of a scientist

Sent to school in England, Medawar attended Marlborough and then Magdalen College, Oxford, where he studied zoology. At Oxford he encountered mentors who treated biology not as stamp-collecting but as a way of asking deep questions about growth, form and individuality. His doctoral work concerned how tissues grow and change shape, and his early papers already show a taste for general ideas alongside meticulous experiment. One senior scientist joked that his first manuscript was “more philosophical than scientific” – a verdict that would have pleased Medawar more than it annoyed him.

Oxford was also where another thread of the Peter Medawar biography began: he met fellow student Jean Shinglewood Taylor, who came to him, she said, to ask the meaning of the word “heuristic”. The conversation turned into a courtship and then a marriage that would later sustain him through illness and give the world a co-author on several books. Her family objected to his Lebanese origins and lack of money; she lost an inheritance but gained an intellectually intense partner whose world mixed science, philosophy and a generous dose of humour.

By the time he finished his doctorate in the early 1940s, the young zoologist had already formed some of the habits that would define this Peter Medawar biography: a habit of asking “awkward” questions, a suspicion of pomp and dogma, and a broad curiosity that made him gravitate toward problems at the boundaries of disciplines – in his case, the frontier between zoology and medicine.

Peter Medawar biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

War, skin grafts and the problem of rejection in the Peter Medawar biography

The Second World War was the first great turning point in the Peter Medawar biography. With Britain under bombardment, surgeons were confronted with soldiers whose bodies were seared by burns. Skin grafting – taking skin from one part of the body to cover a wound elsewhere – became an urgent practical problem. Medawar was drawn into this world through his interest in tissue growth. At military hospitals, he saw that grafts from a patient’s own body could succeed, while grafts from another person would often take at first and then mysteriously fail, sloughing off after a few weeks.

Why did the body accept its own tissue but attack another’s? That question, born over burned limbs and operating tables, would define his career. Medawar began meticulous experiments on skin grafts in animals, refining surgical techniques so that he could separate technical failures from biological ones. He showed that rejection followed a pattern suggestive of a defensive reaction – what we now call the immune response – and that a second graft from the same donor was rejected even faster, as if the body “remembered” the intruder.

From laboratory puzzles to immunological tolerance

In the years after the war, Medawar’s work intersected with a bold theoretical proposal from Australian virologist Frank Macfarlane Burnet. Burnet suggested that the immune system learns to distinguish “self” from “non-self” during early development. If true, it might be possible to create organisms that would treat foreign tissue as their own if exposed to it while still embryos. For a transplantation pioneer already obsessed with graft rejection, this was dynamite.

In collaboration with Rupert Billingham and Leslie Brent, Medawar set up a now-classic series of experiments in mice. They injected cells from one mouse strain into foetal or newborn mice of another strain, then waited until the animals matured. When pieces of skin from the original donor strain were later grafted onto these chimeric adults, the grafts were accepted rather than destroyed. The mice had become specifically tolerant of what should have been foreign tissue. This experimental demonstration of acquired immunological tolerance turned Burnet’s idea into a quantitative theory, and it sits at the heart of every serious Peter Medawar biography.

The implications were immense. If you could reproduce such tolerance in humans, organ transplantation might move from a desperate last resort to a planned, repeatable part of medicine. Although the first successful human kidney transplants were still some years away, the intellectual architecture for them had been built in Medawar’s mouse rooms.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Peter Medawar

Proving acquired immunological tolerance in mice

In 1960, Medawar and Burnet shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for discovery of acquired immunological tolerance”. Nobel committee language is typically dry, but behind the phrase lies a revolution. By showing that the immune system’s sense of self could be reprogrammed, Medawar helped convert transplantation from a philosophical puzzle – how can one body accept another’s tissue? – into a practical clinical strategy.

Medawar’s papers on graft rejection, tolerance and what he sometimes called “the immunological basis of individuality” are dense but surprisingly readable. He had a rare ability to move from detailed observation – the timing of a graft’s failure, the appearance of infiltrating cells – to broad reflections on what it means for an organism to have a biological identity. A careful Peter Medawar biography must note how much these experiments shaped the history of organ transplantation, from early kidney procedures to later heart and liver transplants.

Father of transplantation and the history of organ transplantation

Medawar himself did not transplant human organs; that work fell to surgeons such as Joseph Murray and, later, cardiac surgeons like Norman Shumway, who drew explicitly on the concept of tolerance. But clinicians and historians alike have described Medawar as the “father of transplantation” because his theoretical and experimental work made organ replacement thinkable as routine therapy rather than heroic experiment.

The longer the history of organ transplantation unfolds – from the first kidney successes to today’s complex combined heart–lung operations and even experimental hand and face transplants – the more central this Peter Medawar biography becomes. It is impossible to tell the story of how surgeons learned to persuade the immune system to stand down without stating, at some point, that a bespectacled zoologist with a taste for opera helped show them the way.

For readers wanting a more technical overview of Medawar’s experiments and their place in immunology, a clear educational summary is provided in a biographical sketch from Texas A&M University, which situates his work within the broader history of grafting and immune tolerance in the twentieth century.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Partnerships with Burnet, Billingham and Brent in the Peter Medawar biography

Behind the Nobel medal lies a web of collaborations that any nuanced Peter Medawar biography must explore. Medawar worked closely with Burnet, but also with experimentalists such as Rupert Billingham and Leslie Brent, whose names appear beside his on the classic tolerance papers. Colleagues recall a laboratory atmosphere that mixed rigour with playfulness. Medawar valued scepticism but disliked cynicism; he encouraged students to attack problems, not people.

Many of his collaborators remembered the way discussions in his lab roamed beyond immunology into philosophy, literature and politics. Arguments about experimental controls might slide into debates about Karl Popper or the nature of scientific explanation. In an era when some labs were governed like military units, Medawar’s was more like a salon: hierarchical enough to get things done, but intellectually porous.

Inside the lab: scepticism with warmth

Medawar’s methods were shaped by a conviction that scientific ideas should always be held lightly, no matter how dear they are to their creator. In one of his most-quoted lines, he warned that the intensity of a scientist’s belief in a hypothesis has no bearing on whether it is true; the value of conviction lies only in driving the effort to test it. That stance is visible everywhere in the experiments that drive this Peter Medawar biography: careful controls, a willingness to abandon interpretations that do not fit the data, and a wry humour about his own mistakes.

At the same time, he was not a cold rationalist in person. Friends recall someone who mixed sharp criticism with an almost theatrical charm, lighting up after-dinner conversations with anecdotes and barbed, funny remarks. When he later wrote Advice to a Young Scientist, he channelled these habits into practical counsel: choose problems that matter, be wary of fashion, and remember that science is done by fallible people in untidy institutions, not by abstract logic machines.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

“Is the scientific paper a fraud?” and the Peter Medawar biography

No Peter Medawar biography would be complete without his most provocative question: is the scientific paper a fraud? In a 1960s lecture that has been reprinted and debated ever since, Medawar argued that the standard format of research articles – introduction, methods, results, discussion – gives a dangerously tidy picture of how science actually happens. The real creative process, he suggested, is more like groping in the dark, guided by hunches and half-formed ideas, while the paper pretends that everything arose from a neat deduction.

He did not mean that scientists lied about their data; rather, he accused the genre of misrepresenting thought. By hiding the messy, intuitive, trial-and-error character of discovery, the scientific paper can mislead students about what research really involves. His essay has since become a touchstone in the philosophy of science and in debates about how to teach scientific reasoning.

Limits of science, religion and public debate

Medawar also stirred controversy with his writings on the “limits of science”. In essays and lectures he argued that science is a powerful but bounded way of understanding the world: superb at answering questions about mechanism and cause, but incapable of settling questions of ultimate purpose or moral value. Some religious thinkers welcomed this as a defence of their territory; others saw it as a veiled criticism of metaphysical systems that tried to dress themselves in scientific language.

A textured Peter Medawar biography has to navigate these waters carefully. Medawar was suspicious of sweeping claims, from any side, that pretended to be final. He could be scathing about pseudo-scientific mysticism – his critique of certain grandiose synthesis attempts in mid-century thought is famously withering – but he also rejected the idea that science alone could answer every meaningful question a person might ask. That balance, between admiration and restraint, remains a live issue in today’s culture wars over what “science says”.

Impact of Peter Medawar biography on modern immunology and wider society

From kidney grafts to global transplantation medicine

If one measures impact by lives saved, the story told in any Peter Medawar biography is staggering. Organ transplantation has become part of mainstream medicine, with tens of thousands of procedures performed every year worldwide. The conceptual leap that made those operations safe – the idea that the immune system’s hostility could be selectively damped or redirected – depends heavily on immunological tolerance, the phenomenon bearing Medawar’s experimental fingerprint.

Today, researchers are trying to go even further, developing drugs and protocols that induce tolerance without broadly suppressing immunity, and exploring xenotransplantation: the transplantation of animal organs into humans. That still-developing frontier, covered in detail by high-profile reporting such as a Washington Post account of gene-edited pig kidney transplants, rests on the immunology pioneer’s insight that an immune system can, under certain conditions, be taught to treat the foreign as familiar.

Beyond the clinic, the Peter Medawar biography intersects with medical ethics and public policy. His work contributed to the political will to develop organ-donation systems, frame consent laws and support research into immunosuppressive drugs. Surgeons and policymakers alike still cite his arguments when debating how far transplantation should go and how to manage the risks of tampering with the immune system.

Science writing and public understanding of research

Medawar’s books also changed how scientists and the public talk about science itself. Collections such as The Art of the Soluble and Pluto’s Republic, and later The Threat and the Glory, combined sharply reasoned essays with a conversational tone that many younger writers have tried to emulate. He could, in a few pages, expose the weaknesses of a fashionable thesis or illuminate the human emotions behind a technical dispute.

In that sense, the Peter Medawar biography forms part of the history of science communication. Long before blogs and podcasts, he argued that the public deserved a candid, witty account of how research really works – and that scientists themselves needed such accounts to keep their own mythology in check.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Marriage to Jean and a family of writers

Medawar’s marriage to Jean was not just a romantic partnership but an intellectual collaboration. She co-authored Aristotle to Zoos, an idiosyncratic dictionary of biology, and became a prominent figure in family planning and social reform in her own right. Their household, as described by friends and by their children, sounds like a cross between a seminar and a musical rehearsal: arguments over ideas, laughter, and a great deal of playing records.

The couple raised four children, among them Charles Medawar, who became an influential critic of the pharmaceutical industry, and Caroline, whose son Alex Garland would make his own mark as a novelist and film director. These family threads widen the Peter Medawar biography, showing how questions about science and society carried on into the next generations in unexpected forms.

Opera, cricket and the private philosopher

Friends often described Medawar as an intensely social man who relished conversation, games and music. He played cricket with enthusiasm, listened obsessively to opera, and enjoyed a good argument as much as a well-conducted experiment. At the same time, he had an introspective streak, visible in his later memoir Memoirs of a Thinking Radish, where he reflects with unsparing honesty on his own vanity, ambition and physical frailty.

These human details matter for a rounded Peter Medawar biography. They remind us that the architect of immunological tolerance was also a man who worried about his career, struggled with illness, and found consolation in music, friendships and self-mockery.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Peter Medawar

Stroke, disability and a reimagined career

The stroke that felled Medawar in 1969 came at a cruel moment. He was at the peak of his scientific and institutional power, serving as President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and poised to take on even greater administrative roles. The cerebral haemorrhage left him partially paralysed and impaired his speech. He had to relinquish some positions and reimagine how he could continue as a scientist and writer.

Many people in his situation would have retired quietly. Instead, the late chapters of the Peter Medawar biography show a man who, supported by Jean and by colleagues, learned to work with dictation, adapted his laboratory role and kept publishing. He led a research group at Northwick Park’s Clinical Research Centre, contributed essays that would later be collected in posthumous volumes, and used his authority to advocate for science even as his own body betrayed him.

Books written against the clock

Some of Medawar’s most influential books appeared after his stroke. Advice to a Young Scientist, published in 1979, distilled decades of experience into crisp guidance and has become a classic for early-career researchers. Collections such as The Threat and the Glory assembled essays on topics ranging from reductionism to the role of creativity in research. Knowing he had limited time, he wrote – and dictated – with urgency, a fact that adds poignancy to these works when read alongside any Peter Medawar biography.

He died in 1987 in London, having lived with recurrent strokes for nearly two decades. By then he had received virtually every honour British science could bestow, including the Order of Merit and, fittingly for a great communicator, the Royal Society’s Michael Faraday Prize for advancing public understanding of science.

The Lasting Legacy of Peter Medawar biography

Prizes, lectures and buildings in his name

The institutional afterlife of Medawar’s work is unusually rich. The Royal Society created the Medawar Lecture, later folded into the Wilkins–Bernal–Medawar Lecture, to honour contributions to the history, philosophy and social role of science. Transplantation societies award Medawar Medals for research that advances the field he helped found. At Oxford, the Peter Medawar Building for Pathogen Research stands as a concrete reminder that his influence extends into contemporary studies of infection and immunity.

These honours matter not just as decorations, but because they keep certain questions alive: How should scientific institutions engage with government? How can research serve the public without becoming a political tool? A thoughtful Peter Medawar biography shows that he spent as much time grappling with such questions as he did counting graft survival days in mice.

Why Peter Medawar biography still matters in today’s science

In an age of genome editing, personalised medicine and renewed interest in xenotransplantation, the concerns running through this Peter Medawar biography feel strikingly current. The idea that biological identity is negotiated rather than fixed underpins not only transplantation but also debates about autoimmunity, cancer immunotherapy and even microbiome research. Meanwhile, his critique of scientific storytelling speaks directly to worries about hype, reproducibility and public trust in expertise.

To read a carefully constructed Peter Medawar biography today is therefore to learn more than the life story of a single immunology pioneer. It is to see how one person tried to hold together honesty about the messiness of research, compassion for patients whose bodies failed them, and delight in the “art of the soluble” – the set of problems that science, at its best, can genuinely hope to solve. Understanding that Peter Medawar biography helps us understand something bigger: how modern science grows when it remains self-critical, humane and open to surprise.

Frequently Asked Questions about Peter Medawar biography

Q1: Who was Peter Medawar and why is he often called the father of transplantation?

Q2: What is the main scientific achievement highlighted in a Peter Medawar biography?

Q3: How did Peter Medawar’s wartime work influence his later research on immunology?

Q4: What did Peter Medawar mean when he asked whether the scientific paper is a fraud?

Q5: How did Peter Medawar cope with his stroke and continuing disability?

Q6: Why is Peter Medawar’s writing still recommended to young scientists today?