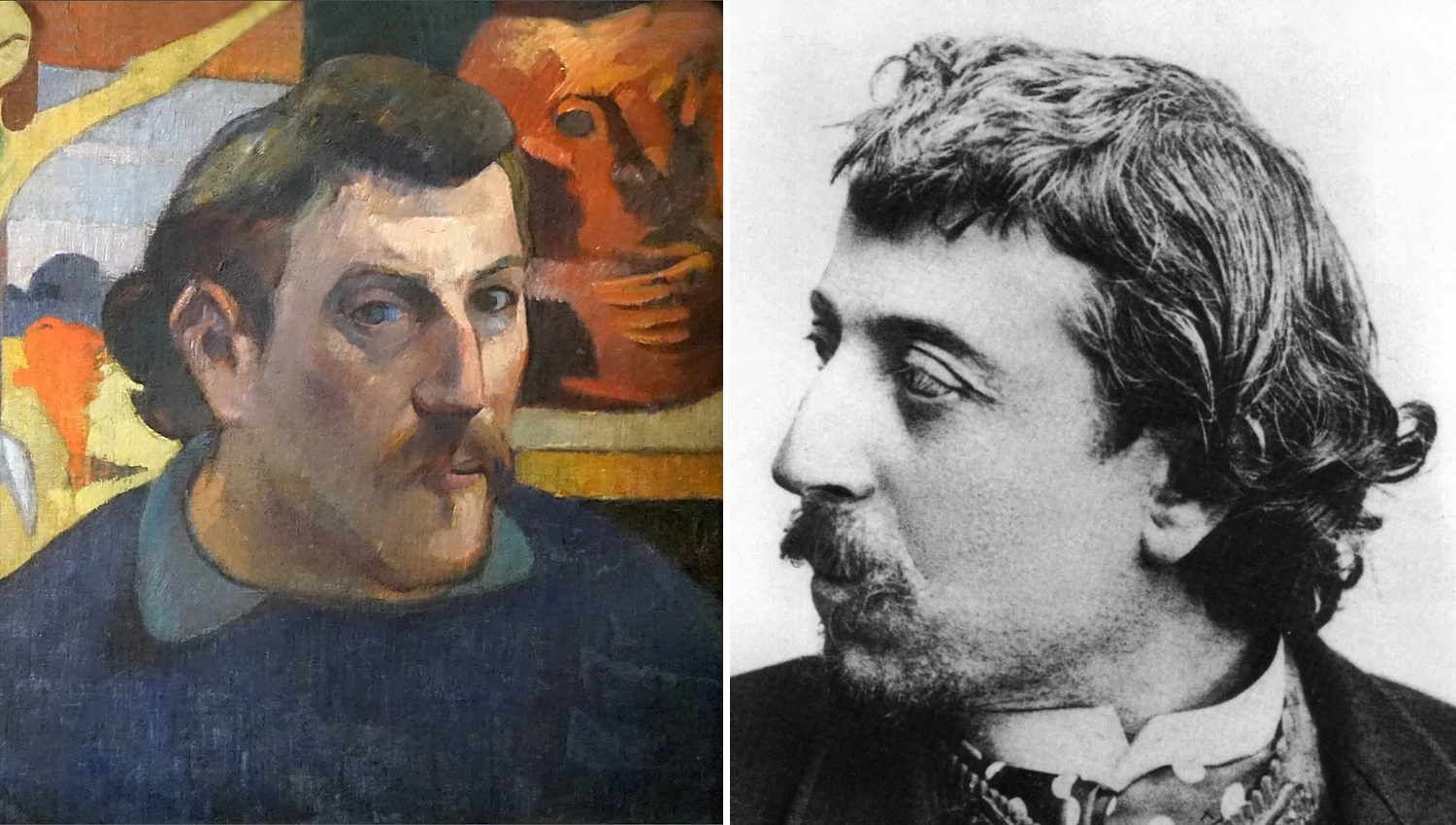

Few figures in the history of modern art embody defiance and transformation like Paul Gauguin. Often misunderstood in his lifetime, Gauguin’s deep artistic instincts led him away from the salons of Paris and into the heart of the South Pacific, where he redefined the boundaries of color, form, and cultural representation. Today, the Paul Gauguin art legacy continues to shape the way we understand creativity, symbolism, and artistic rebellion.

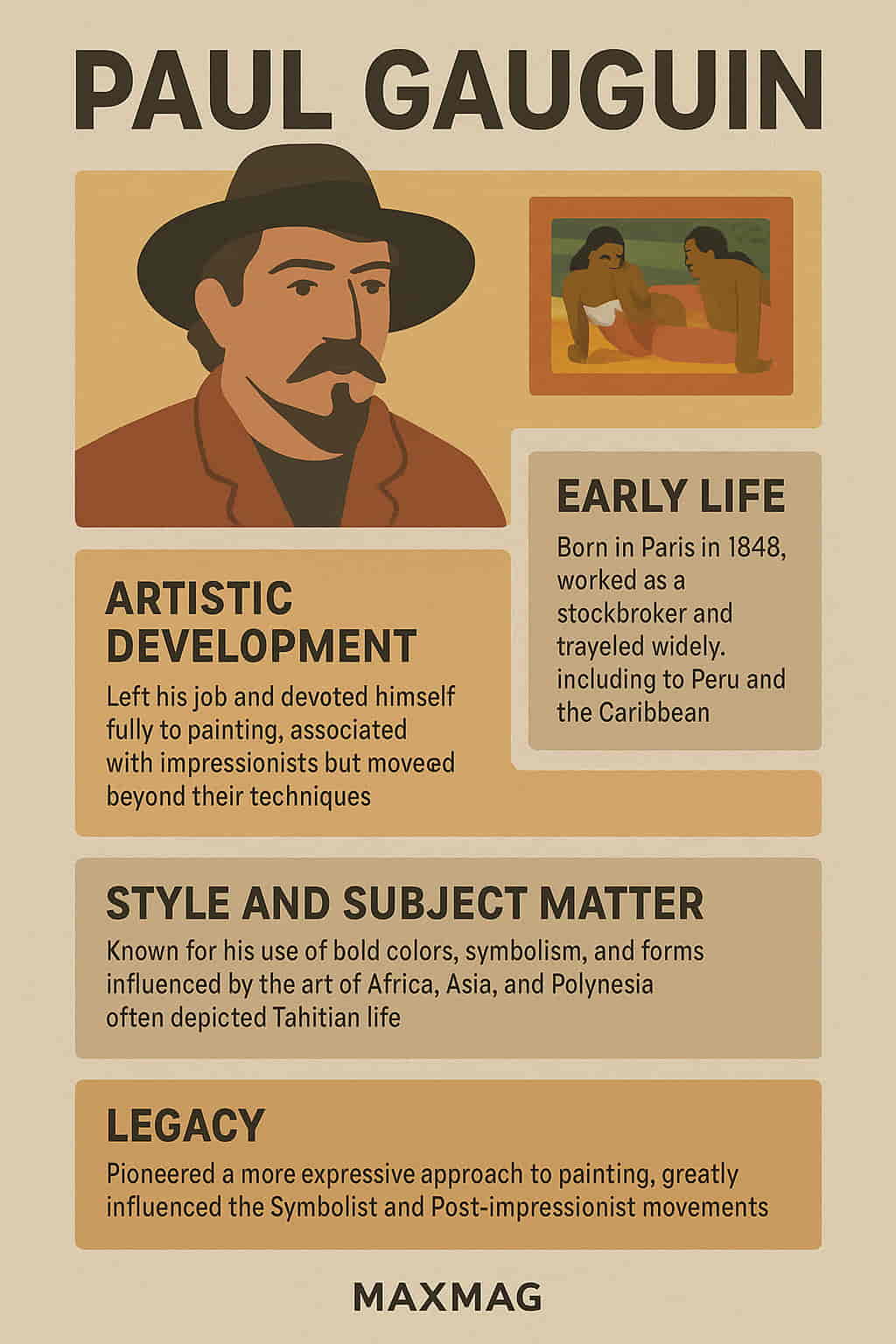

Born in Paris in 1848, Paul Gauguin’s life began amid social upheaval. His father, a journalist with strong republican ideals, died en route to Peru, where the family sought refuge during France’s political turmoil. As a result, young Paul spent formative years in Lima, absorbing colors, folklore, and patterns that would later echo in his art. Upon returning to France, he entered the French merchant navy at 17, then became a stockbroker—a profession that gave him financial stability, but little fulfillment.

In the evenings, he painted. His early works show the influence of the Impressionist movement, especially the works of Camille Pissarro, with whom he often painted en plein air. By the early 1880s, Gauguin had committed fully to art, quitting finance and enduring financial hardships. He exhibited with the Impressionists but soon diverged in style and philosophy.

Who Was Paul Gauguin?

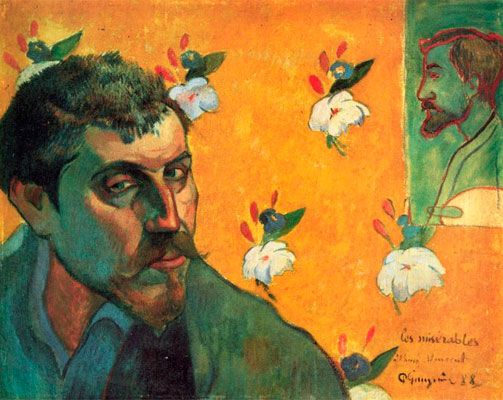

While he began under the shadow of artists like Monet and Degas, Paul Gauguin soon sought a more symbolic and emotional mode of expression. As the 1880s progressed, his friendship with Émile Bernard led him to develop Synthetism—a method combining outward appearance, artist feelings, and symbolic meaning.

In this period, Gauguin’s color palette intensified. He abandoned realism for flat, vibrant colors and spiritual motifs. This stylistic shift would become a hallmark of the Paul Gauguin art legacy, influencing entire movements from Symbolism to Fauvism. His growing dissatisfaction with industrial Europe prompted a dramatic move that would transform his life and legacy forever.

Paul Gauguin Art Legacy from Tahiti

In 1891, Gauguin left France for Tahiti, seeking what he called “a paradise unspoiled by civilization.” The island’s lush vegetation, mythic folklore, and radiant light offered him fresh inspiration. His works from this era—like Te aa no areois and Manao tupapau—use broad areas of color and flattened perspective to depict an imagined, mythologized Tahitian world.

However, Gauguin’s relationship with Tahiti was far from innocent. His works often exoticized native women and imposed a Western lens on Polynesian spirituality. His life there was riddled with ethical complexities, including relationships with very young local girls. Despite these troubling realities, Tahiti remains central to the Paul Gauguin art legacy, both for its aesthetic impact and the difficult conversations it continues to provoke in art history.

In 1895, following a brief return to France, Gauguin permanently resettled in Polynesia. His most ambitious canvas, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, was completed during this period—a deeply philosophical work intended as his final artistic statement.

Controversy and Isolation

Gauguin’s life was not only marked by aesthetic exploration but also personal alienation. He was often in conflict with authorities—religious, colonial, and artistic. His letters from the South Pacific, especially to fellow artists and art dealers in France, reveal a man bitter about rejection but passionate about artistic purity. He envisioned himself as a prophet of a new artistic gospel, far removed from bourgeois conventions.

This self-image permeated both his writings and paintings. Even as his health declined from syphilis and alcohol abuse, Gauguin refused to compromise his ideals. He settled in the Marquesas Islands and built a home he called “Maison du Jouir” (“House of Pleasure”), where he continued to paint until his death in 1903.

Gauguin’s Major Works and Their Meaning

The Paul Gauguin art legacy is inseparable from a handful of masterpieces that continue to captivate audiences and scholars.

- Vision After the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel) (1888): Painted during his time in Brittany, this work juxtaposes a biblical struggle with Breton women in traditional dress, using non-naturalistic color and bold outlines—a stark departure from Impressionism.

- Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892): Perhaps his most controversial work, it portrays a young Tahitian girl lying on her stomach, wide-eyed with fear, as a ghostly figure looms behind her. While stunning in its chromatic boldness, the painting embodies colonialist undertones that modern viewers must grapple with.

- Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897): Considered his magnum opus, this canvas compresses an entire philosophy of existence into a single panorama, from birth to death, embedded with Polynesian and Buddhist symbols.

These works not only represent milestones in his career but also anchor the broader conversation about identity, spirituality, and artistic autonomy—core themes within the Paul Gauguin art legacy.

Influence on Modern Art

Gauguin’s revolutionary use of color, composition, and non-Western themes laid the groundwork for many 20th-century artists. Pablo Picasso openly credited Gauguin’s Tahitian paintings as an influence during his development of Cubism. Similarly, Henri Matisse’s vivid color fields reflect Gauguin’s experiments in emotional chromatics.

Beyond painting, his influence extended into literature, theater, and critical theory. The Symbolist movement embraced his belief in the power of suggestion over representation. Postmodern critics would later reinterpret his work through lenses of gender, colonialism, and cultural appropriation, ensuring that the Paul Gauguin art legacy remains both rich and contested.

Today, his paintings are housed in the world’s greatest museums—MoMA in New York, the National Gallery in Washington, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, and more. The National Gallery of Art and MoMA continue to feature Gauguin’s work, allowing audiences to engage with his genius—and its contradictions—up close.

Gauguin’s Time in Brittany: A Bridge Between Worlds

Before his celebrated voyages to Polynesia, Gauguin found an important transitional space in Brittany—a region in northwest France that blended Catholic mysticism with rural simplicity. He spent extended periods in Pont-Aven and Le Pouldu in the late 1880s, where he gathered around him a small circle of avant-garde painters, later known as the Pont-Aven School. These artists, inspired by Gauguin, moved away from Impressionism’s fleeting effects and toward solid forms and symbolic abstraction.

In Brittany, Gauguin explored the idea of art as a spiritual vision rather than a mirror of nature. This is especially visible in The Yellow Christ (1889), one of his most iconic paintings from the region. The crucified Christ is depicted in flat yellow tones, set against a background of Breton women in prayer. The work merges religious imagery with local culture, presenting Gauguin’s bold philosophy: that the sacred could be reimagined through color, symbolism, and folk traditions.

This was also the period when he famously declared, “Art is either plagiarism or revolution.” That credo would become a defining thread of the Paul Gauguin art legacy, seen not only in his break from traditional Western painting but also in his insistent belief that art must confront the viewer’s expectations.

Gauguin’s Philosophical Vision

More than a painter, Gauguin was a thinker deeply engaged with the metaphysical. He kept notebooks and journals—especially the posthumously published Noa Noa—which combined travelogue, myth, and personal reflection. In them, he often grappled with existential themes: the origin of life, the nature of humanity, and his role as an artist-shaman.

His visual works mirror these obsessions. In Day of the Gods (1894), the central figure resembles a deity carved from stone, surrounded by human figures symbolizing birth, ritual, and death. The water reflects multiple shades—red, pink, and blue—blurring the boundaries between spiritual vision and material world.

What makes the Paul Gauguin art legacy so unique is precisely this convergence of ideas: a painter whose canvas was both a dreamscape and a philosophical battlefield. He anticipated the Symbolist movement’s desire to look inward, yet also laid the emotional groundwork for Expressionism.

Gauguin did not merely paint what he saw; he painted what he believed the world meant. This core idea made his work both profound and, at times, controversial—especially as modern viewers reassess the colonialist underpinnings of his interpretations.

Later Years in the Marquesas: Isolation and Immortality

In 1901, Gauguin relocated from Tahiti to Hiva Oa in the Marquesas Islands, where he built a home engraved with provocative wood carvings. Far from the artistic centers of Europe, he entered a period of deep introspection and declining health, but also one of remarkable productivity.

There, he painted Barbarian Tales (1902) and Riders on the Beach, characterized by increasingly surreal landscapes and symbolic references drawn from Polynesian mythology, Buddhism, and Catholicism. These late works carry a haunting quality—a sense of finality. His colors darkened, his forms grew more rigid, but his symbolic language became more potent.

He also waged an open feud with colonial administrators and missionaries. He wrote pamphlets decrying their hypocrisy and the destruction of indigenous culture. Though embattled and sick, he fought to preserve what he saw as vanishing wisdom in native traditions.

Despite this, Gauguin remained a figure of contradiction. He revered what he considered the spiritual purity of indigenous life, yet imposed his Western fantasies onto their stories and appearances. These complexities have only deepened scholarly debate around the Paul Gauguin art legacy, sparking books, documentaries, and exhibitions that both celebrate and critique his achievements.

Gauguin’s Global Legacy in Museums and Markets

Gauguin’s art commands astronomical prices in today’s market. In 2015, his painting Nafea Faa Ipoipo (When Will You Marry?) sold for a reported $210 million, placing it among the most expensive artworks ever sold. This reflects not only his cultural cachet but also the continued fascination with his mythos.

Major institutions across the world host Gauguin retrospectives, often accompanied by critical re-evaluations. The Tate Modern in London, the Getty Museum, and the Art Institute of Chicago have all organized shows that delve into the contradictions of his work, particularly around race and gender.

Digital platforms, too, are contributing to the expansion of the Paul Gauguin art legacy. Augmented reality exhibitions, like those featured on Google Arts & Culture, allow global audiences to explore his canvases in extraordinary detail, fostering both admiration and critical dialogue.

Gauguin and the Politics of Reappraisal

In recent years, museums and cultural institutions have begun to confront the troubling elements of Gauguin’s life. His relationships with underage girls in Tahiti, and his romanticized depictions of colonized peoples, are no longer glossed over but contextualized within broader conversations about power, representation, and exploitation.

Some galleries have chosen to include content warnings or add interpretive panels next to his work. Others have invited Indigenous curators or feminist scholars to co-create exhibitions that examine Gauguin from new perspectives. Far from diminishing his legacy, these reappraisals have made it more nuanced and resonant with contemporary audiences.

The complexity of the Paul Gauguin art legacy is not a weakness—it is its defining strength. By sitting at the crossroads of beauty and controversy, spirituality and conquest, Gauguin’s work forces us to reckon with the contradictions of the human condition, and of art itself.

The Lasting Impact of Paul Gauguin

A century after his death, Gauguin’s art remains vividly alive. It pulses with tropical reds and spiritual blues, with longing and rebellion. Artists from Frida Kahlo to Jean-Michel Basquiat have cited him as a reference—some embracing his visual language, others challenging his gaze.

In a modern world hungry for authenticity, Gauguin’s life and work offer both inspiration and caution. He dared to leave the known in pursuit of the mysterious. He used color not to imitate the world but to recreate it, to suggest inner truth over outer realism.

To understand Gauguin is not to excuse him, but to explore the tensions between genius and ethics, beauty and blindness. The enduring relevance of the Paul Gauguin art legacy lies in its capacity to provoke: visually, emotionally, and intellectually. It asks us not just to look—but to look deeper.

FAQ: Paul Gauguin and His Enduring Legacy

Q: What style of painting is Paul Gauguin best known for?

A: Gauguin is most associated with Primitivism and Synthetism, using bold color and symbolic content.

Q: Where can I see Gauguin’s artwork today?

A: Major works are held in MoMA (New York), Musée d’Orsay (Paris), and the National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C.).

Q: What makes the Paul Gauguin art legacy so influential?

A: His use of color, incorporation of non-Western elements, and rejection of realism laid the groundwork for modernism.

Q: What are Gauguin’s most famous paintings?

A: Where Do We Come From?, Spirit of the Dead Watching, and Vision After the Sermon.

Q: Did Gauguin and Van Gogh work together?

A: Yes, briefly in Arles in 1888, though their personalities clashed, leading to Van Gogh’s famous ear-cutting episode.