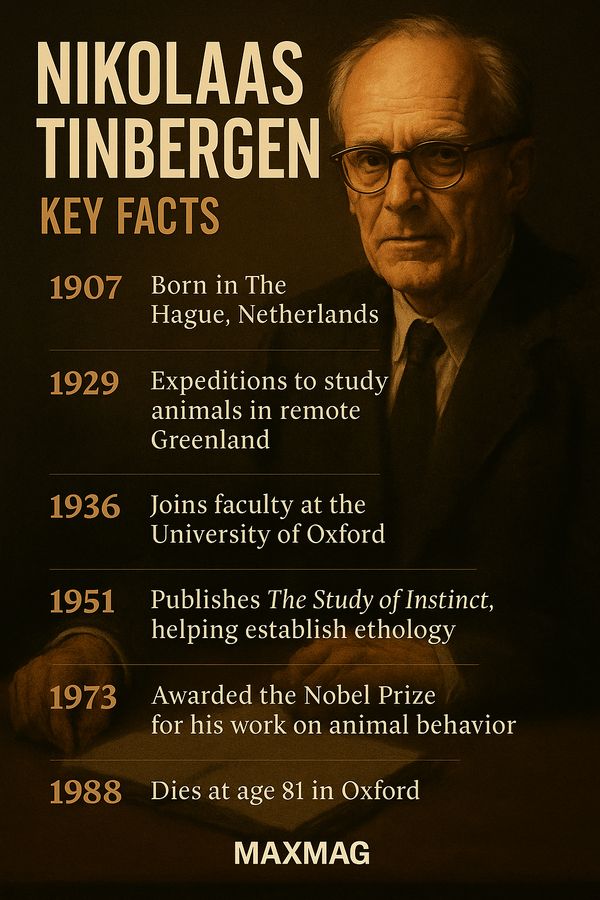

Anyone trying to make sense of animal behaviour ends up, sooner or later, walking through the pages of a Nikolaas Tinbergen biography. The Dutch-born ethologist spent his life watching foxes, sticklebacks and herring gulls and turned those patient observations into a new way of doing biology. In this Nikolaas Tinbergen biography, the shy field naturalist becomes a central figure in twentieth-century science: a Nobel laureate who taught researchers to ask four deceptively simple questions about behaviour — how it works, how it develops, what it is for and how it evolved.

Those four questions, set out in a landmark 1963 paper, still structure how animal behaviour, evolutionary psychology and behavioural ecology are taught. Yet the story behind them is not a straightforward tale of scientific triumph. It is also a story about war and imprisonment, about depression and doubt, about a man who tried — with mixed results — to apply lessons from gulls and geese to troubled children and stressed modern humans. A full Nikolaas Tinbergen biography has to hold all these threads together.

At a glance: Nikolaas Tinbergen

- Who: Dutch zoologist and ethology pioneer, co-founder of the modern scientific study of animal behaviour.

- Era: Born 1907 in The Hague, died 1988 in Oxford; active during the formative decades of twentieth-century biology.

- Headline contributions: Tinbergen’s four questions, classic field experiments on gulls and fish, and a leading role in establishing ethology as a rigorous science.

- Why he matters today: The Nikolaas Tinbergen biography underpins how researchers connect brain, behaviour, evolution and environment — from conservation biology to neuroscience and psychology.

Early Life and Education in the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography

Childhood in The Hague and a love of the outdoors

Nikolaas Tinbergen was born in 1907 in The Hague, the son of a schoolteacher and a mother who filled the house with books and conversation. By his own account he was a reluctant pupil, more interested in skipping class to roam the dunes and watch birds than in reciting multiplication tables. This tension between classroom discipline and the pull of the natural world runs through any honest Nikolaas Tinbergen biography: from the start, he learned more from skylarks and shorebirds than from blackboards.

Field guides were scarce, and binoculars a luxury, so the young Niko trained his eyes the hard way — by standing still for long stretches, noticing details others skimmed over. Where neighbours saw a flock of “seagulls”, he saw individuals with distinct calls, squabbles and routines. That habit of slow, meticulous watching would later become a methodological signature, distinguishing the new ethology pioneer from laboratory-bound psychologists of his time.

From Leiden lecture halls to Arctic ice

After school Tinbergen went to Leiden University to study biology, not because he had a carefully mapped career plan, but because it seemed the only way to continue his life outdoors. At Leiden he absorbed the then-standard zoology curriculum, heavy on anatomy and taxonomy, but he was drawn to the few lecturers who talked about living animals in their own habitats rather than pinned specimens on trays. The Nikolaas Tinbergen biography begins here to intersect with the broader history of biology, as new ideas about evolution, behaviour and ecology were taking shape.

A formative experience came when he joined an expedition to Greenland, living among Inuit hunters and watching Arctic animals in conditions that would have defeated many temperate-zone naturalists. The rough fieldwork — digging snow shelters, tracking birds across ice floes — taught him that good behavioural science could not be done solely from lecture notes. Later, as an ethology pioneer, he would insist that his students learn to live with their study animals, not just visit them.

These early years laid down themes that recur throughout the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography: a preference for real landscapes over laboratory corridors, a suspicion of overly tidy theories, and a deep belief that careful description is not the opposite of explanation, but its starting point.

Nikolaas Tinbergen biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

Watching herring gulls on windswept dunes

Back in the Netherlands, Tinbergen settled on birds — especially herring gulls and terns — as his main research subjects. He and his wife Elisabeth set up camp on the windswept dunes of the Dutch coast, raising their own children among nests and chick colonies. Where a casual beach visitor heard a noisy blur, Tinbergen heard a sophisticated communication system of calls, postures and ritualised movements.

He began to ask simple but radical questions. Why do gulls remove the broken eggshells from the nest after hatching? Why do chicks peck at a particular spot on the parent’s bill to solicit food? Why do adults attack some intruders but not others? Each question led to an experiment that now reads like a parable in the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography: swapping artificial eggs of different colours, placing cardboard models in territories, painting extra spots on beaks to see what chicks found irresistible.

From simple observations to Tinbergen’s four questions

Out of this hands-on fieldwork grew one of the most influential frameworks in modern biology. In a 1963 paper, Tinbergen argued that any full explanation of a behaviour must answer four kinds of question: about its mechanism, its development, its function and its evolutionary history. This move is one of the central turning points in the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography, transforming him from a gifted observer of animals into a theorist of how explanations themselves should be organised.

In practice, Tinbergen’s four questions forced researchers to think in layers. A bird song, for instance, can be explained in terms of hormones and neural circuits (mechanism), learning during a sensitive juvenile period (development), attracting mates or defending territory (function), and the song’s divergence from ancestral patterns across related species (phylogeny). The Nikolaas Tinbergen biography becomes, in this sense, a cornerstone of behavioural science history: it showed that arguments over “nature versus nurture” were too crude, because behaviour had to be understood along multiple axes at once.

Today, university courses in animal behaviour, psychology and neuroscience still use these four questions as a scaffolding, testimony to just how deeply Tinbergen’s simple schema reshaped the field.

Key Works and Major Contributions in the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography

The Study of Instinct and the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography of fixed action patterns

In 1951 Tinbergen published The Study of Instinct, a book that crystallised many of his ideas about innate behaviour and what he called “fixed action patterns” — stereotyped responses triggered by specific stimuli. This volume is often treated as the backbone of any serious Nikolaas Tinbergen biography, because it pulled together years of scattered papers into a coherent view of how animal behaviour could be studied systematically.

Fixed action patterns included behaviours like the egg-rolling of geese, the attack responses of territorial fish, and the head-tossing displays of courting birds. Tinbergen showed that these patterns were not rigid reflexes but could be modulated by context, motivation and learning. Yet they were stable enough that slight changes in the stimulus could produce strikingly exaggerated responses. His experiments with “supernormal stimuli”, such as over-sized fake eggs or unnaturally intense colour patches, revealed just how tuned animals could be to simple cues.

For readers wanting to see how these ideas appeared in Tinbergen’s own words, the Smithsonian Libraries preserve an English translation of his wartime monograph on innate behaviour, a precursor to his later book, in their collections of classic animal behaviour texts. The Smithsonian summary of Tinbergen’s early work on innate behaviour offers a glimpse of how his thought developed from early observations to mature theory.

Building a discipline: journals, films and textbooks

Tinbergen did not shape ethology only through experiments and theory. He also helped build its institutions. He co-founded the journal Behaviour, providing a home for careful field studies at a time when many mainstream journals favoured more reductionist physiology. In the 1960s he worked with filmmakers to produce wildlife documentaries that doubled as visual case studies in ethology, introducing television audiences to concepts like imprinting, signalling and ritualised aggression.

Popular books such as The Herring Gull’s World and Social Behaviour in Animals distilled complex research into accessible narrative, bringing lay readers into the observational world that the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography describes. These works did more than entertain: they showed that animal behaviour, properly observed, could illuminate everything from parenting strategies to cooperation and conflict.

By the time he shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discoveries about the organisation and elicitation of behaviour patterns, Tinbergen had become a central figure in mid-century biology. The Nobel committee’s decision to honour “mere animal watchers”, as he half-jokingly put it, signalled that ethology had moved from the margins to the centre of science.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Field notebooks, kitchen-table experiments and makeshift labs

One of the most striking features of the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography is its emphasis on method. Tinbergen refused to separate observing from experimenting. On the dunes, he and his students would first spend weeks simply watching, sketching and listing behaviours — an “ethogram” in ethology’s technical language. Only then would they design small, tightly focused experiments to test how changes in stimuli affected those behaviours.

Many of these experiments were almost comically low-tech: painted sticks, cardboard cut-outs, eggs dyed with household paints. Some were conducted on kitchen tables or in gardens, with family members drafted in to help move models or time responses. Yet underneath the improvised equipment lay a disciplined logic of controls, comparisons and repeated trials that would not have looked out of place in a high-end laboratory.

This approach made Tinbergen a model for generations of animal behaviourists who lacked big budgets but did have access to wild or semi-wild animals. It also explains why the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography looms large in conservation biology and behavioural ecology: he showed that clever design and deep knowledge of natural history could answer questions that no amount of fancy machinery alone could touch.

Working with Lorenz, von Frisch and a new generation

Collaboration runs like a thread through Tinbergen’s story. Alongside the Austrian Konrad Lorenz and the Austrian–German Karl von Frisch, he helped define ethology as a distinct discipline. Together they demonstrated that carefully designed field experiments could reveal the rules underlying apparently messy animal lives. Their shared Nobel Prize recognised this joint achievement, but it also cemented a powerful trio at the heart of behavioural science history.

At Oxford, Tinbergen built a thriving animal behaviour research group. Among his doctoral students were future luminaries such as Richard Dawkins, Marian Dawkins, Desmond Morris and Iain Douglas-Hamilton. The Nikolaas Tinbergen biography is therefore also a story about mentorship. He did not simply hand down theories; he gave his students problems, pushed them back into the field when their hypotheses became too neat, and insisted they write clearly enough that non-specialists could follow.

By modelling a blend of rigour and curiosity — and by showing that close observation and evolutionary thinking could coexist — Tinbergen helped bridge gaps between zoology, psychology and emerging fields like behavioural ecology.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

From “mere animal watcher” to contested authority

The Nobel Prize elevated Tinbergen to global fame, but it also brought his ideas under harsher scrutiny. Some physiologists and molecular biologists remained unconvinced that field observations and relatively simple experiments deserved the same status as work on cells and genes. Part of the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography, then, is about a shift in scientific authority: the gradual acceptance that behaviour, too, could be studied with the same seriousness as biochemistry.

There were also internal debates within ethology and psychology. Not everyone agreed on how “innate” fixed action patterns truly were, or how much weight should be given to evolutionary function versus learning and flexibility. Tinbergen himself revised some of his positions over time, acknowledging that the boundaries between instinct and learning were more porous than earlier ethologists had believed.

Autism, ethological therapy and the limits of analogy

The most controversial chapter in the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography came late in his career, when he and Elisabeth turned their attention to autism. Drawing analogies from their work on animal fear and stress, they proposed that many autistic behaviours stemmed from early disturbances in the mother–child bond, and they promoted a “holding therapy” in which parents would embrace distressed children for prolonged periods to rebuild trust.

These ideas attracted fierce criticism from clinicians and researchers. They were seen as lacking solid empirical support and, more seriously, as reviving parent-blaming theories that many in the autism field had been working hard to dismantle. Accounts from autistic people and their families later described some applications of holding therapy as distressing or even traumatic. Any responsible Nikolaas Tinbergen biography has to confront this episode: his attempt to export ethological concepts into human psychiatry illustrates both the power and the danger of cross-species analogy.

If his work on autism showed a blind spot, it also sparked debates that helped clarify what counts as evidence in human behavioural research, and highlighted the importance of listening to the voices of those directly affected by scientific theories.

Impact on Ethology and on Wider Society

Why Tinbergen’s four questions still organise behavioural science

Sixty years after they were first proposed, Tinbergen’s four questions are still routinely used to structure research papers, lectures and entire textbooks. They help students and scientists distinguish between “how” and “why” explanations, between developmental history and evolutionary function. In that sense, the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography is inseparable from the intellectual architecture of modern ethology and behavioural ecology.

The framework has proved especially useful in fields where different levels of explanation can easily become tangled. In neuroscience, for example, researchers use Tinbergen’s questions to keep track of how neural circuits, hormone systems, developmental processes and evolutionary pressures each contribute to a behaviour. In evolutionary psychology, they serve as a reminder that claims about function must be backed by evidence about history, not just plausible stories.

In conservation biology and animal welfare science, Tinbergen’s emphasis on observing animals in naturalistic settings has encouraged practitioners to design enclosures, enrichment and management practices that respect species-typical needs, rather than treating animals as interchangeable objects.

Influence beyond biology, from psychology to economics

One of the more surprising side notes in the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography is how far his influence has spread beyond zoology. His conceptual tools have been adopted in human psychology, anthropology and even economics, where scholars have used the four-question framework to think about the evolution and function of social institutions and decision-making.

Part of this broader impact reflects the Tinbergen family story. Nikolaas’s brother Jan Tinbergen was a pioneering econometrician and the first recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. Together, though in different domains, the brothers helped normalise the idea that complex systems — whether markets or animal societies — could be studied with a blend of observation, modelling and theory.

Popular science writers and journalists have also leaned on Tinbergen’s ideas when explaining animal behaviour to general audiences. A contemporary Los Angeles Times obituary of Tinbergen, for instance, emphasised not only his Nobel Prize but his ability to reveal the sophistication of everyday creatures, shifting public attitudes away from seeing animals as simple automatons.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Family life, pacifism and post-war scars

Behind the careful prose of scientific papers, the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography contains a more fragile, human story. During the Second World War he was imprisoned by the occupying Nazi forces in the Netherlands, an experience that left deep emotional scars. The brutal disruption of academic life, and the knowledge that colleagues and Jewish friends were being targeted, reinforced his scepticism toward nationalism and authoritarianism.

After the war, Tinbergen and his family moved to Oxford, where they settled into a comparatively quiet domestic pattern. He married Elisabeth Rutten, herself a keen observer and collaborator in his fieldwork, and together they raised five children. Visitors to their home later recalled a modest household, more cluttered with field notes, bird models and children’s toys than with trophies or symbols of status.

Politically and philosophically, Tinbergen leaned toward a gentle humanism. He was wary of dogma, whether religious or scientific, and preferred concrete evidence over grand ideological claims. This temperament shaped how he reacted to fame: the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography is notably free of the kind of self-promotion that can accompany scientific celebrity.

A shy public figure who loved simple pleasures

Colleagues describe Tinbergen as shy in large groups but animated when talking one-on-one about an experiment or a bird behaviour that puzzled him. He disliked pomp and ceremony, finding the rituals surrounding prizes and honorary degrees faintly absurd. On field trips he was happiest in old clothes, binoculars around his neck, scribbling in his notebook while wind and rain battered the hide.

He also struggled with depression, particularly later in life. Friends and biographers recount long periods of low mood and self-doubt, during which he feared he might follow the path of his brother Luuk, a biologist who died by suicide. Treatment and support from the psychiatrist John Bowlby, whose attachment theory Tinbergen admired, helped him manage these episodes. These struggles are an important part of the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography because they remind us that scientific brilliance does not insulate anyone from mental illness.

In quieter moments, Tinbergen found solace in carving, photography and long walks. These hobbies were not a distraction from his work so much as an extension of the same impulse: to look closely, to notice patterns, to pay attention.

Later Years and Final Chapter of the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography

From Nobel ceremonies to quiet Oxford streets

The Nobel Prize in 1973 marked both a high point and a turning point. For a time, Tinbergen found himself in demand as a lecturer and public intellectual, asked to comment on everything from animal rights to human aggression. He used his Nobel lecture to argue that ethology could help medicine understand stress-related diseases, and he took the opportunity to praise the Alexander technique, a posture and movement method he believed could ease modern burdens on the body and mind.

But the public attention also weighed on him. The Nikolaas Tinbergen biography shows a man who preferred the company of students and animals to that of committees and dignitaries. As the years passed, he retreated somewhat from high-profile roles, focusing instead on writing, mentoring and his controversial work on autism.

Illness, withdrawal and a late turn to human problems

In the 1970s and 1980s, Tinbergen’s health declined. He suffered a stroke in 1983 and never fully recovered his physical strength. Nevertheless, he continued to think and write about what he saw as “civilisation diseases” — conditions like depression and anxiety that he believed arose when ancient behavioural adaptations collided with modern lifestyles.

These late-life speculations are an ambiguous part of the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography. On the one hand, they show a scientist unwilling to stay in a narrow lane, determined to ask how his work on animal behaviour might illuminate human suffering. On the other hand, some of his forays into psychiatry and autism research over-reached the available evidence and underestimated the complexity of human social environments.

Tinbergen died in December 1988 at his home in Oxford, following another stroke. Obituaries stressed not only his scientific achievements but also his personal modesty and his role in changing how both scientists and the public think about animal minds.

The Lasting Legacy of the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography

How his questions shape today’s ethology pioneer work

Looking back, it is striking how much of contemporary behavioural science still sits within the frame that Tinbergen built. Researchers studying everything from seabird migration to human cooperation routinely structure their explanations along his four axes. Modern neuroethology — the study of how nervous systems generate natural behaviour — is, in many ways, a direct descendant of the conceptual world mapped out in the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography.

His insistence on combining field observation with experiment continues to influence conservation strategies, zoo design and wildlife management. When scientists assess whether a captive environment allows “natural behaviour”, they are, knowingly or not, speaking in Tinbergen’s language of function, development and evolutionary history.

Why understanding the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography still matters

At a time when biology is often associated with gene-sequencing machines and brain scanners, the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography is a reminder that some of the deepest insights still come from watching whole animals in real environments. Tinbergen’s life story encourages a kind of intellectual humility: before building grand theories or computational models, go and look carefully at what animals actually do.

It also offers a cautionary note. His missteps in autism research show how easily analogies between species can mislead, especially when they intersect with sensitive issues like parenting and mental health. To read the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography closely is to learn not only how to ask better questions about behaviour, but also how to recognise the limits of one’s expertise.

In the end, what makes Nikolaas Tinbergen stand out in the history of science is not only his Nobel Prize or his famous four questions, but his stubborn commitment to curiosity. He believed that even the most ordinary animal could surprise us if we watched long enough and asked the right kinds of questions. Understanding the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography helps us see that this attitude — patient, critical, humane — is as important to modern science as any new piece of technology.

Frequently Asked Questions about Nikolaas Tinbergen biography

Q1: Who was Nikolaas Tinbergen and why is his work important?

Q2: What are Tinbergen’s four questions in animal behaviour?

Q3: How does the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography relate to the history of ethology?

Q4: Why did Tinbergen win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine?

Q5: What controversies surround the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography, especially regarding autism?

Q6: How is the Nikolaas Tinbergen biography relevant to science and society today?