On a winter evening in the late 1830s, a disillusioned lawyer turned botanist peered down a microscope in a German laboratory and saw something that would change biology forever. This is the heart of the Matthias Schleiden biography: a story of failure and reinvention that led a troubled Hamburg attorney to become one of the architects of cell theory, the idea that every living thing is built from microscopic units called cells. In the space of a decade, he moved from courtroom to classroom, from depression to discovery, helping to shift life science from descriptive plant catalogues to a new, cellular view of nature.

To follow the Matthias Schleiden biography is to watch a nineteenth-century mind wrestling with new instruments, new evidence and old habits of thought. Schleiden helped formulate the idea that plant tissues are made of cells, anticipated the central role of the nucleus and, together with zoologist Theodor Schwann, offered a unified picture of life that still underpins modern biology. At the same time, he clung to mistaken ideas about how cells arise, quarreled with colleagues and cultivated a reputation as both a brilliant lecturer and a difficult man.

Matthias Schleiden at a glance

- Who: Matthias Jakob Schleiden, German botanist and early cell theorist.

- Era: Born 1804 in Hamburg, active in the mid-nineteenth century.

- Headline contribution: Argued that all plant tissues are composed of cells and highlighted the central role of the nucleus.

- Why he matters today: His work helped launch cell theory, a foundation of modern biology and medicine.

Early Life and Education of Matthias Schleiden

Family roots and a lawyer’s beginning

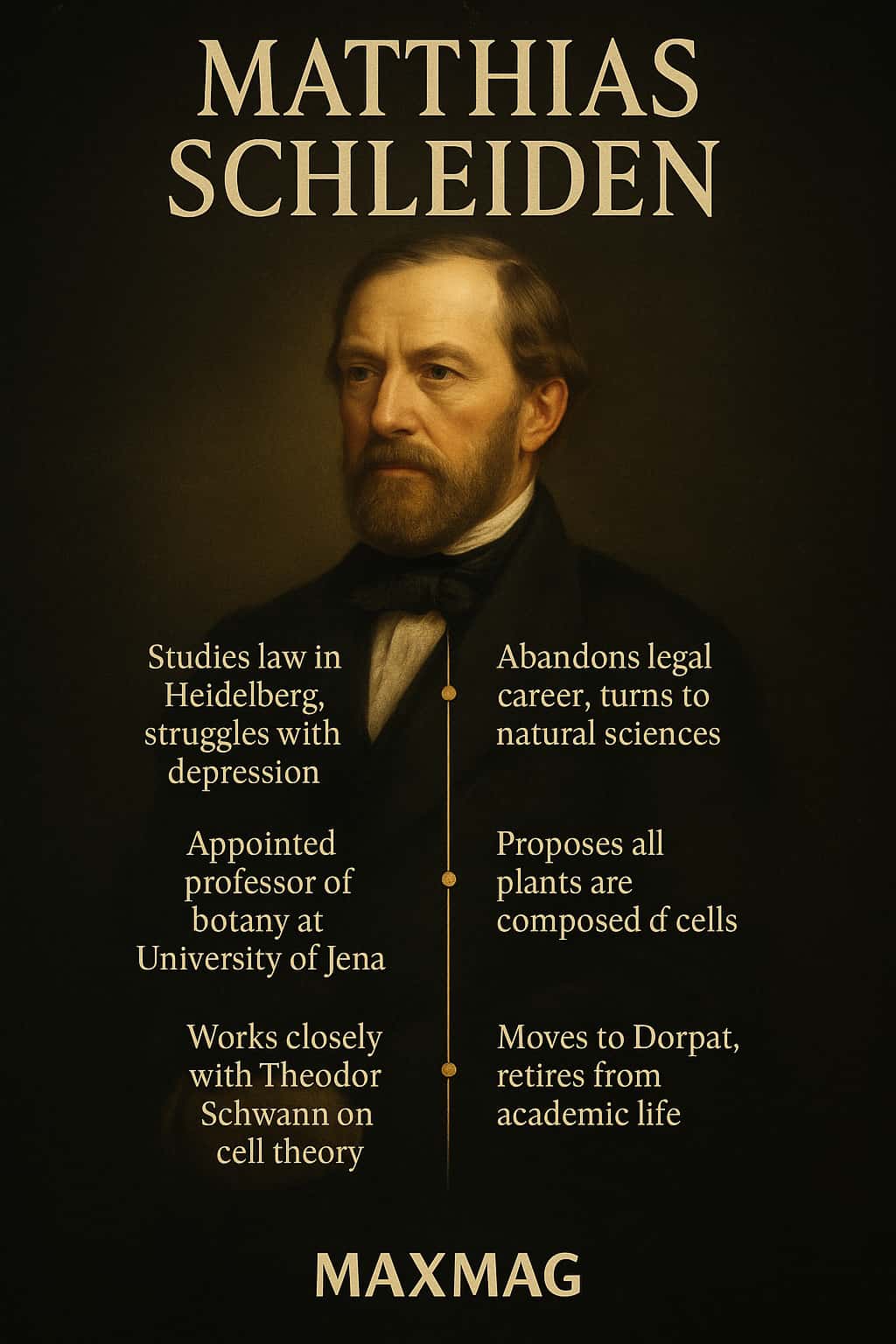

The Matthias Schleiden biography begins far from the world of microscopes. Born in Hamburg in 1804, into a prosperous merchant family, he was expected to pursue a respectable, stable profession. Botany was not the plan. As a young man he studied law at Heidelberg, following a conventional path shaped by family expectations rather than personal passion. He qualified, returned to Hamburg and opened a legal practice, stepping into the role of a bourgeois lawyer in a rapidly changing German port city.

It did not go well. Schleiden’s legal practice faltered, and so did his mental health. He felt boxed in by routine cases and the narrow horizons of commercial law. The Matthias Schleiden biography is marked early on by a serious depressive episode, culminating in a suicide attempt that left him shaken and searching for a different kind of life. That crisis, as much as any lecture or book, pushed him toward science.

Crisis, illness and a late turn to botany

After his breakdown, Schleiden withdrew from legal work and gravitated to the study of plants, first as a solace, then as a vocation. He moved back into university life, studying medicine and natural science, and eventually came under the influence of leading botanists of the day. He was not a prodigy who had loved biology from childhood; the Matthias Schleiden biography is that of a late convert who brought the intensity of a second life to his new field.

In lecture halls and small laboratories, Schleiden encountered the new generation of microscopes and the emerging discipline of plant anatomy. He read widely, absorbing Robert Brown’s description of the nucleus in plant cells and the broader currents of nineteenth-century science. Within a few years, he had reinvented himself as a botanist, joining a small but growing community intent on understanding plants from the inside out rather than merely cataloguing their external features.

By the end of this chapter, the Matthias Schleiden biography has already taken one of its sharpest turns: from Hamburg solicitor to ambitious, microscope-wielding scientist. That sense of rupture would colour how he approached ideas, allies and rivals for the rest of his life.

Matthias Schleiden biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

Inside the microscope: from plant tissues to cell theory

The central episode in any Matthias Schleiden biography unfolds at the eyepiece of a microscope. In the 1830s, Schleiden examined thin slices of plant tissue—leaves, stems, embryos—stained and mounted on glass. Under magnification he saw repeating units: small compartments bordered by walls, each containing a darker body, the nucleus. He became convinced that these “cells” were not incidental details but the basic building blocks of plant life.

What sounds obvious now was radical then. Many botanists still thought in terms of continuous, undifferentiated tissues. Schleiden argued instead that every plant organ, from the soft tissue of a leaf to the wood of a tree trunk, could be understood as a community of cells. This was an early, plant-focused step toward what would become classical cell theory, the now-standard idea that all living things are made of cells, and that cells are the structural units of life.

How a chance meeting shaped the Matthias Schleiden biography

In 1837, at a dinner in Berlin, Schleiden met Theodor Schwann, a zoologist wrestling with the structure of animal tissues. The encounter has become one of the set pieces in any Matthias Schleiden biography: over conversation and sketches, Schleiden described plant cells and their nuclei; Schwann realised that animal tissues showed strikingly similar units. If plants and animals shared the same microscopic architecture, perhaps there was a single biological principle at work.

Over the next two years, Schleiden and Schwann exchanged ideas and publications that converged into a unified cell theory: plants and animals alike are built of cells, and the cell is the fundamental unit of life. Their work did not drop out of a clear blue sky; it drew on decades of improving microscopes and earlier observations. But Schleiden’s insistence on the centrality of the nucleus and the universality of cells helped give those scattered facts a compelling framework.

By the close of this section, the Matthias Schleiden biography has shifted from personal reinvention to intellectual breakthrough. A man who had once felt superfluous in the law now laid claim to a place at the centre of a new biological narrative.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Matthias Schleiden

“Beiträge zur Phytogenesis” and the first plant cell manifesto

In 1838, Schleiden published his most famous paper, “Beiträge zur Phytogenesis” (“Contributions to Phytogenesis”). In compact but forceful prose, he set out the argument that plants are made of cells and that these cells originate around a nucleus. The article has become the anchor point of every serious Matthias Schleiden biography, often described as a kind of manifesto for a new, cell-centred botany.

Schleiden’s emphasis on the nucleus was particularly influential. He saw it not as a passive inclusion but as the starting point of cell formation, dubbing it the “cytoblast”—the cell-builder. Although later work would correct some of his details, that focus on the nucleus as a vital structure proved prescient, foreshadowing its role as the carrier of genetic information. For plant biology, “Beiträge zur Phytogenesis” was a pivot: it proposed that an entire kingdom of life could be understood in terms of repeated cellular units rather than vague vital forces.

Textbooks, lectures and popular science writing

The Matthias Schleiden biography is not just a story of one landmark paper. In the 1840s he wrote a major botany textbook, “Grundzüge der wissenschaftlichen Botanik” (“Foundations of Scientific Botany”), which helped spread the new cellular perspective across Germany and beyond. He was a gifted lecturer, known for clear explanations and a flair for connecting laboratory findings to broader questions about life and development.

Schleiden also embraced the role of popular science writer. He penned essays and gave public talks that introduced educated lay readers to the idea of cells, the structure of plants and the promise of microscopy. In an age when science was becoming more specialised, this willingness to speak across boundaries is part of what makes the Matthias Schleiden biography so compelling. He showed that a detailed, technical concept like cell structure could be woven into stories that captured the imagination of non-scientists.

Taken together, these works helped ensure that cell theory did not remain confined to a small circle of specialists. They turned Schleiden into a recognisable public figure, a status that would both help and complicate his career in the decades to come.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style in the Matthias Schleiden biography

Working with Theodor Schwann: parallel paths, shared vision

The partnership between Matthias Schleiden and Theodor Schwann is central to the history of cell theory. They never formed a formal laboratory team in the modern sense, but the dialogue between plant and animal research was crucial. Schleiden brought the perspective of plant tissues; Schwann scrutinised nerve and muscle. Both believed that the microscope could reveal general laws of life, not just interesting shapes.

Their collaboration was also a clash of temperaments. The zoologist Schwann was by most accounts mild-mannered and cautious, whereas Schleiden was combative and self-assured. Letters and later reminiscences suggest that each man felt he had grasped the central insight first. These tensions foreshadow the priority disputes that later dog the Matthias Schleiden biography, yet the scientific outcome—a unified cell theory—depended on their interplay.

Laboratories, lenses and the craft of nineteenth-century microscopy

Schleiden worked at a time when microscopes were improving but still imperfect. Focusing was finicky; lenses introduced distortions; staining techniques were experimental. The craft of preparing plant sections—slicing them thin enough for light to pass through, mounting them without crushing—was as important as the theory. Any serious Matthias Schleiden biography has to acknowledge how much of his insight depended on this hands-on, artisanal side of science.

In this respect, Schleiden was very much a nineteenth-century experimentalist. He drew, diagrammed and compared, using visual evidence to build generalisations. Today, students learning the basics of cell theory might encounter a concise list of principles in a textbook or in an online tutorial from a university biology department. A modern example is the University of Arizona’s overview of cell theory, which distils the idea into three clear rules about cells and life while still tracing it back to Schleiden and Schwann’s work in the 1830s. This kind of educational resource connects directly back to the painstaking observations that filled Schleiden’s notebooks.

The working style that emerges from the Matthias Schleiden biography is one of intense focus at the bench, combined with a willingness to generalise boldly from limited evidence. That mixture would drive both his achievements and his mistakes.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Free cell formation and why Schleiden got it wrong

For all his successes, Schleiden made a major error that later cell biologists had to correct. He believed that new cells could form inside a kind of nutrient fluid, crystallising around a nucleus like ice forming in water. This “free cell formation” idea fit with some older views about spontaneous generation and seemed to explain how complex plant tissues could arise.

The problem was that it wasn’t true. As microscopes improved and more careful observations accumulated, scientists such as Robert Remak and Rudolf Virchow showed that cells divide from pre-existing cells rather than appearing fully formed in a homogeneous fluid. Virchow’s famous phrase, omnis cellula e cellula—every cell from a cell—became a cornerstone of modern cell theory, and Schleiden’s crystallisation model was quietly retired. In most tellings of the Matthias Schleiden biography, this mistake is now treated as a reminder that even pioneering scientists can hold on to outdated ideas.

Priority disputes and the politics of nineteenth-century science

The history of cell theory is threaded with arguments about who deserves credit. Some contemporaries and later historians have accused Schleiden of overstating his originality, pointing out that he borrowed from earlier work on plant structure and from Brown’s discovery of the nucleus. Others note that he sometimes downplayed contributions from colleagues, a trait that did little to soften his reputation in the tight-knit world of German science.

These disputes can make the Matthias Schleiden biography feel like a courtroom drama—fitting for a former lawyer. But they also highlight how scientific revolutions rarely belong to one person. Schleiden’s role was to synthesise, argue and publicise, to give cellular observations a coherent narrative. That talent for framing ideas, even imperfectly, is part of why his name remains attached to the story of cell theory nearly two centuries later.

In summarising this chapter, it is fair to say that Schleiden’s scientific record is mixed: remarkable insights about plant cells and nuclei, coupled with a stubborn commitment to free cell formation and a keen eye for personal credit. That tension is one of the things that make the Matthias Schleiden biography more human than heroic.

Impact on Cell Biology and on Wider Society

From nineteenth-century botany to modern cell biology

It is impossible to teach basic biology today without, in some sense, revisiting the Matthias Schleiden biography. Every school diagram showing a plant cell with its wall, nucleus and chloroplasts rests on the nineteenth-century realisation that such structures are universal features of plant life. Schleiden’s insistence that plants are cellular organisms helped move biology toward what historians call a “cellular worldview”—the idea that life is best understood in terms of microscopic units and their interactions.

That cellular worldview is now the backbone of fields ranging from genetics to cancer research. When doctors examine tissue under a microscope to diagnose disease, or when researchers trace how a virus invades a host cell, they are working within a framework that stretches back to Schleiden, Schwann and Virchow. Modern accounts of cell science, such as reviews of Siddhartha Mukherjee’s book on the cell and the future of medicine in the Washington Post, place this nineteenth-century cell theory alongside today’s cutting-edge therapies, underlining how deeply embedded it is in biomedical thinking. Those narratives often nod to Matthias Schleiden as one of the original architects of the cell-based view of life.

Why the Matthias Schleiden biography still matters for today’s biology classrooms

In classrooms, the story of cell theory often appears as a neat timeline: Hooke discovers “cells” in cork, Schleiden and Schwann propose the theory, Virchow adds “every cell from a cell.” The fuller Matthias Schleiden biography complicates that linear story. It shows students that science involves false starts, personal struggles and contested claims as well as tidy breakthroughs.

For teachers, Schleiden’s life offers a way to humanise abstract ideas. The image of a man who walked away from a failing legal practice, nearly lost to despair, then found meaning by staring down a microscope gives emotional weight to lecture slides about plant tissues. It also makes the history of biology more inclusive, reminding students that the development of cell theory was not solely the work of a few flawless geniuses but of flawed, striving individuals working within particular social and technological limits.

In that sense, the Matthias Schleiden biography is itself a teaching tool—a narrative bridge between the nineteenth-century laboratory and the twenty-first-century science classroom.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Melancholy, ambition and a difficult temperament

Contemporary portraits and later accounts describe Schleiden as intense, eloquent and sometimes abrasive. The early depression that nearly ended his life never entirely receded; the Matthias Schleiden biography is threaded with hints of recurring melancholy. At the same time, he possessed a fierce ambition, a desire not just to contribute quietly but to be seen as a leading voice in German science.

This combination could make him a difficult colleague. He was quick to criticise rivals and slow to acknowledge errors. Friends and students admired his rhetorical gifts, his ability to turn a lecture on plant anatomy into a broader reflection on life and growth. But some fellow scientists bristled at his self-assured tone and his insistence on certain ideas, such as free cell formation, long after counter-evidence had accumulated.

Public intellectual, private doubts

Away from the lectern, Schleiden cultivated the life of a public intellectual. He wrote essays on science and culture, commented on education and engaged in debates about the role of natural science in society. The Matthias Schleiden biography thus overlaps with the broader story of nineteenth-century German liberalism, in which discussions of biology often carried political and philosophical overtones.

Yet beneath the confident public persona, there were private doubts. Letters suggest that he remained haunted by the fear of failure that had engulfed his legal career. The very intensity with which he defended his scientific positions may have been, in part, a response to that earlier collapse. This inner conflict makes his story resonate with anyone who has reinvented themselves mid-life and then worried that the new path might also slip away.

Here, the Matthias Schleiden biography ceases to be just a chapter in the history of cell theory and becomes a more universal tale about identity, work and the search for meaning.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Matthias Schleiden

From Jena to Dresden: the elder statesman of botany

In his later career, Schleiden held academic posts at the University of Jena and later in Dresden, where he continued to teach, write and lecture. He enjoyed the status of an established authority in plant science, even as younger researchers with newer techniques began to refine and sometimes overturn his conclusions. The Matthias Schleiden biography at this point resembles that of many nineteenth-century pioneers: celebrated for foundational work, yet increasingly out of step with the cutting edge.

He did not retreat quietly. He remained outspoken on scientific and educational issues, positioning himself as a defender of what he saw as rigorous empirical science against both speculative philosophy and narrow technical specialisation. His later writings broadened in scope, touching on topics from development to the place of science in culture, even as his direct laboratory contributions waned.

Death, obituaries and early assessments

Matthias Jakob Schleiden died in 1881, by which time cell theory had been firmly embedded in biological thinking and extended by advances in embryology, pathology and, soon, genetics. Obituaries in German scientific journals emphasised his role in championing the idea of the cell as the basic unit of plant structure, while also noting that his views on cell formation had not stood the test of time.

Early assessments of his legacy were shaped by these mixed feelings. Some historians cast him as a crucial but transitional figure, a botanist who helped open the cellular era but failed to grasp all its implications. Others emphasised his courage in breaking with older, non-cellular views of plant anatomy. Modern scholarship tends to place the Matthias Schleiden biography alongside those of Schwann and Virchow, seeing them as part of a network of thinkers whose converging efforts produced one of biology’s most important theories.

By the end of his life, the restless Hamburg lawyer had long since vanished, replaced by the image of a grey-haired professor whose name would forever be linked to the cells he once traced in pencil sketches under flickering lamplight.

The Lasting Legacy of Matthias Schleiden biography

Remembering a flawed pioneer of cell theory

Looking back, the lasting legacy of Matthias Schleiden biography lies less in a single flawless theory than in his role in shifting the questions biologists asked. By insisting that plants are made of cells and that the nucleus is central to their structure, he helped move biology toward a framework in which living things are analysed from the bottom up, starting with their smallest units. That framework now underlies modern fields from molecular genetics to stem-cell research.

At the same time, Schleiden’s mistakes and blind spots remain instructive. His commitment to free cell formation shows how easy it is for even good scientists to see what they expect rather than what the evidence demands. His quarrels over priority remind us that science is a human enterprise, shaped by ego and rivalry as well as by data. The Matthias Schleiden biography, taken whole, invites us to celebrate the genuine achievements of a cell theory pioneer while also acknowledging the messy, contingent process by which scientific knowledge is made.

In an age when biology continues to probe ever deeper into the cell—its genes, membranes, signalling networks—the story of Matthias Schleiden offers perspective. It reminds us that today’s sleek diagrams and digital images have their roots in grainy nineteenth-century views and in the stubborn curiosity of people who, like Schleiden, were willing to start their lives over in pursuit of a better way to see the living world.

Frequently Asked Questions about Matthias Schleiden biography

To round off this exploration of Matthias Schleiden’s life and work, here are answers to some common questions that readers often have about him and his role in the history of cell theory.