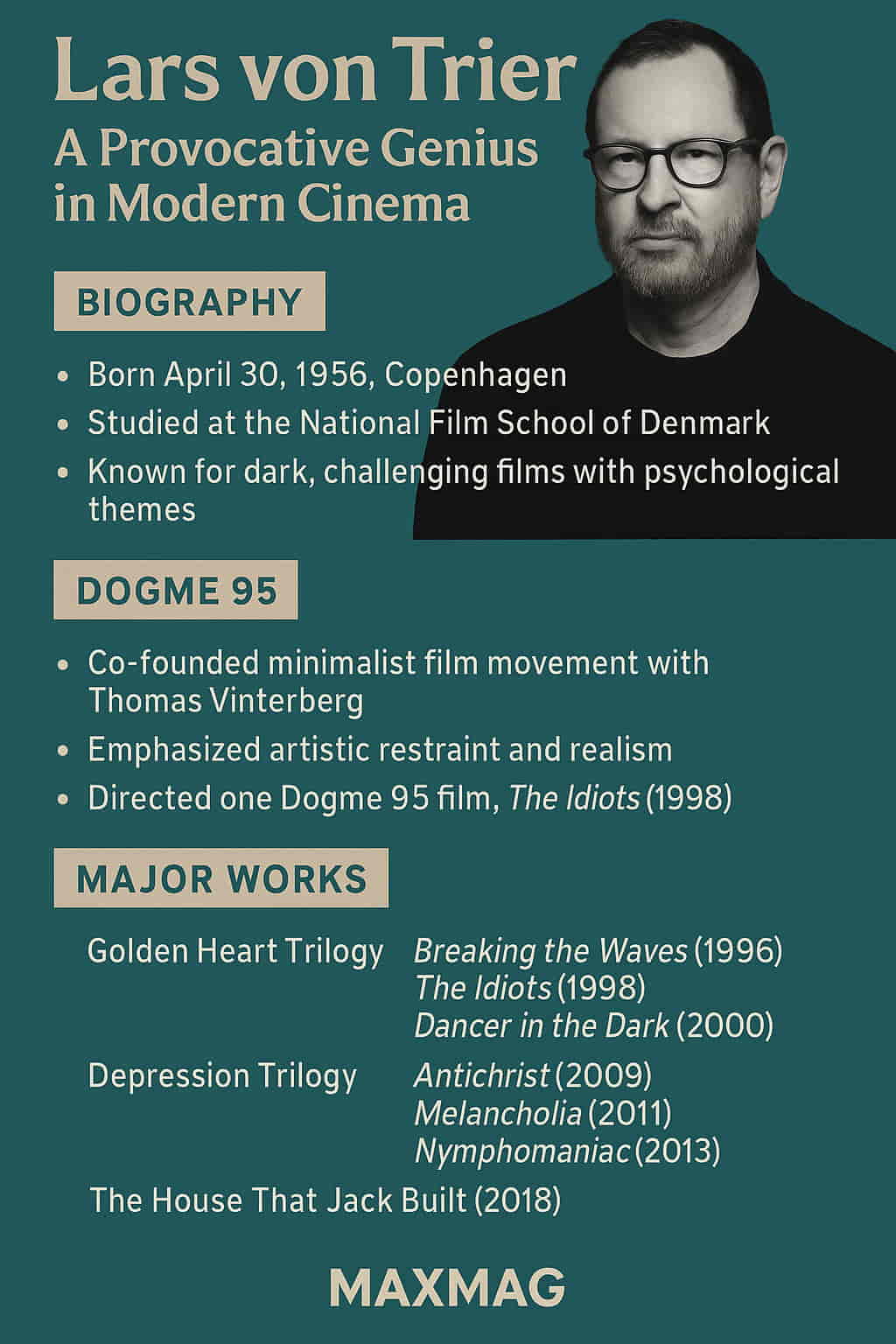

Lars von Trier remains one of the most influential, polarizing, and intellectually provocative filmmakers in contemporary cinema. His films are not designed for comfort; rather, they are emotional minefields that dissect pain, guilt, morality, and the boundaries of artistic expression. Through this in-depth Lars von Trier movie analysis, we examine how his life, philosophies, and daring creative choices have forged a legacy that is both celebrated and condemned — sometimes simultaneously.

A Complex Childhood: The Origins of Von Trier’s Psychology

Born Lars Trier on April 30, 1956, in Copenhagen, Denmark, the future auteur spent much of his youth steeped in emotional isolation and intellectual conflict. His mother, a politically radical nudist and atheist, raised him in an unconventional household with strict rules but little warmth. She revealed to him on her deathbed that the man he believed to be his father was not biologically related to him, a trauma that would haunt von Trier for decades.

Even at a young age, von Trier was drawn to storytelling and filmmaking. His early experiments with an 8mm camera were a mix of horror and surrealism — hinting at a mind that would later revolutionize how we view suffering and redemption on screen. These foundational years weren’t merely autobiographical; they became the emotional DNA of his cinematic worlds.

After enrolling in the Danish National Film School in the late 1970s, von Trier immediately stood out for his technical mastery and provocative ideas. His graduation film, Images of Liberation (1982), addressed World War II and moral ambiguity — a theme he would revisit many times. It was during his film school years that he added the aristocratic “von” to his name, partly as a joke and partly as a self-mythologizing move that would set the tone for his public persona.

Dogme 95: Cinematic Minimalism as Moral Manifesto

In 1995, von Trier and fellow Danish director Thomas Vinterberg launched the Dogme 95 movement, a radical manifesto rejecting special effects, artificial lighting, and narrative formulas. The “Vow of Chastity” was both a return to storytelling basics and a philosophical rebellion against the consumerist polish of mainstream cinema.

Von Trier’s contribution to this movement was The Idiots (1998), a raw, handheld film that follows a group of adults who feign mental disability in public as an act of resistance against societal norms. Unsettling, often offensive, and intellectually charged, the film challenged audiences and critics alike to reconsider their relationship with cinematic realism.

🔗 Learn more about the Dogme 95 legacy at IndieWire.

Even though von Trier only made one true Dogme film, the movement reshaped indie filmmaking around the world. From American mumblecore to European arthouse cinema, Dogme’s influence is seen in countless projects that prize truth over spectacle.

The Golden Heart Trilogy: Innocence in the Face of Brutality

Von Trier’s next artistic leap came with the Golden Heart Trilogy, composed of Breaking the Waves (1996), The Idiots (1998), and Dancer in the Dark (2000). These films are thematically unified by female protagonists who undergo extreme suffering without abandoning their moral or spiritual purity.

Breaking the Waves tells the harrowing story of Bess, a devout woman who sacrifices everything for her paralyzed husband’s happiness. The film’s visual aesthetic — rough, grainy textures with natural lighting — mirrors the emotional abrasiveness of the narrative. It earned Emily Watson an Oscar nomination and secured von Trier the Grand Prix at Cannes.

In Dancer in the Dark, Icelandic artist Björk stars as Selma, a Czech immigrant going blind while working in a factory to save money for her son’s eye surgery. This tragic musical won the Palme d’Or in 2000 and is a cornerstone in any Lars von Trier movie analysis due to its blend of genre, emotion, and relentless despair.

These films reflect von Trier’s fascination with martyrdom. His heroines suffer not because they are weak, but because they are unwavering in their beliefs — an inversion of Hollywood’s idea of strength.

🔗 Explore the making of Dancer in the Dark via The Criterion Collection.

Mental Illness and the Depression Trilogy

Von Trier has spoken openly about his own clinical depression, anxiety, and dependence on medication. These struggles directly influenced the creation of the Depression Trilogy, consisting of Antichrist (2009), Melancholia (2011), and Nymphomaniac (2013). Each film offers a brutal, beautiful, and often disturbing look into the fractured psyche of its protagonists.

-

Antichrist, starring Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg, is a psychological horror set in a cabin in the woods where grief and guilt spiral into sadomasochistic violence and metaphysical terror.

-

Melancholia is perhaps his most elegant work, using the metaphor of an approaching planet to explore the immobilizing effects of depression. Its slow motion, Wagner-scored opening is one of the most celebrated sequences in modern European cinema.

-

Nymphomaniac, divided into two volumes, chronicles the life of Joe, a woman addicted to sex, through conversations with an old bachelor who finds her wounded in an alley.

Each film demands patience and emotional resilience, but the reward is profound. In this Lars von Trier movie analysis, it becomes clear that these films aren’t merely confessional; they are philosophical investigations into human nature.

🔗 For a clinical breakdown of Melancholia’s portrayal of depression, visit Psychology Today.

Art or Exploitation? The Ongoing Controversies

Controversy is a constant shadow in von Trier’s career. In 2011, during a Cannes press conference for Melancholia, he joked about having sympathy for Hitler — a statement that led to his temporary ban from the festival. Though he apologized profusely, many viewed the incident as indicative of his recklessness and poor judgment.

Actors, too, have voiced conflicting opinions about working with him. Björk claimed her experience on Dancer in the Dark was emotionally abusive, while others like Charlotte Gainsbourg have repeatedly collaborated with him, praising his intense creative vision.

So is von Trier a sadist or a misunderstood genius? The truth may lie somewhere in between. What’s undeniable is that he treats cinema as a space for profound ethical experimentation. His films are not comfortable, but neither is life — a viewpoint that anchors any authentic Lars von Trier movie analysis.

🔗 For an overview of Cannes controversies, check Variety.

Visual Style and Cinematic Language

Beyond his narratives, von Trier is known for a unique visual grammar that rejects gloss in favor of rawness. Some hallmarks include:

-

Handheld camerawork with abrupt zooms and shaky framing

-

Abrupt editing and lack of transitional scenes

-

Sparse or experimental sound design

-

Breaking the fourth wall and self-referential storytelling

-

A blend of surrealism and hyperrealism

His use of digital video, often considered cheap or amateurish in the 1990s, became pioneering. Films like The Idiots and Dogville (2003) used minimalist sets and painted floor outlines to highlight the artificiality of cinema, drawing the audience’s attention to the constructed nature of storytelling itself.

The Necessity of Lars von Trier Movie Analysis

Why do von Trier’s films deserve deep analysis, despite their brutality or controversy? Because they operate not on the plane of plot or entertainment, but on the level of moral inquiry. His films provoke us to ask: What is suffering? What is love? Can redemption exist without punishment?

This makes Lars von Trier movie analysis not just an academic exercise but a philosophical one. Just as we study Dostoevsky or Nietzsche to understand human complexity, we dissect von Trier to grapple with moral ambiguity and the limits of empathy.

Recent Works and Where He’s Headed

Von Trier’s latest major release is The Kingdom Exodus (2022), a continuation of his earlier surreal hospital series Riget. It returns to a darker form of humor while incorporating the metaphysical dread that has come to define his style.

At 69, von Trier has expressed doubt about his future projects due to Parkinson’s disease. Still, his legacy is vast and evolving. Younger filmmakers — including Yorgos Lanthimos, Ari Aster, and Robert Eggers — have cited his influence.

He may never receive universal acclaim, but then again, he never wanted it. Lars von Trier is not here to please. He’s here to provoke, unearth, and transform.

FAQ

Q: What is Lars von Trier’s most acclaimed film?

A: Dancer in the Dark (2000), which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, is often cited as his most celebrated — though Breaking the Waves and Melancholia are also highly respected.

Q: Why are his films considered disturbing?

A: Von Trier explores themes like grief, sexual trauma, and death with graphic imagery and emotional intensity, often without moral resolution.

Q: Is von Trier’s work autobiographical?

A: Many of his films draw from his personal battles with depression and anxiety, making them deeply introspective though not literal autobiography.

Q: Where can I watch his films legally?

A: His work is available on platforms like Criterion Channel, MUBI, and Apple TV.

Q: Is there a best order to watch his films?

A: For a structured experience, begin with Breaking the Waves, followed by the Golden Heart and Depression trilogies, and then move into his more experimental work like Dogville and The House That Jack Built.

Q: What sets him apart from other directors?

A: Von Trier prioritizes emotional truth and moral inquiry over narrative closure. He consistently rejects commercial expectations in favor of personal, intellectual storytelling.