One autumn morning in rural Austria, a man in a worn shirt and rubber boots walks across a meadow, trailed by a long, wobbling procession of grey goslings. To the birds, he is not a scientist but a parent. To the wider world, that man would become the public face of a new science of animal behaviour. This is the heart of the Konrad Lorenz biography: a story of a boy who wanted to be a goose, a researcher who helped found modern ethology, and a public intellectual whose life would later be shadowed by his entanglement with Nazism.

Told properly, the Konrad Lorenz biography is not just a tale about cute ducks and Nobel Prizes. It is also about how twentieth-century science tried to understand instinct, aggression and the fragile bond between humans and nature—while wrestling with its own political compromises and blind spots. Lorenz’s work on imprinting and instinct revolutionised how biologists, psychologists and teachers thought about animal minds, yet it also carried assumptions that later generations would challenge. To follow his path is to watch modern science discovering both its power and its moral limits.

Konrad Lorenz biography at a glance

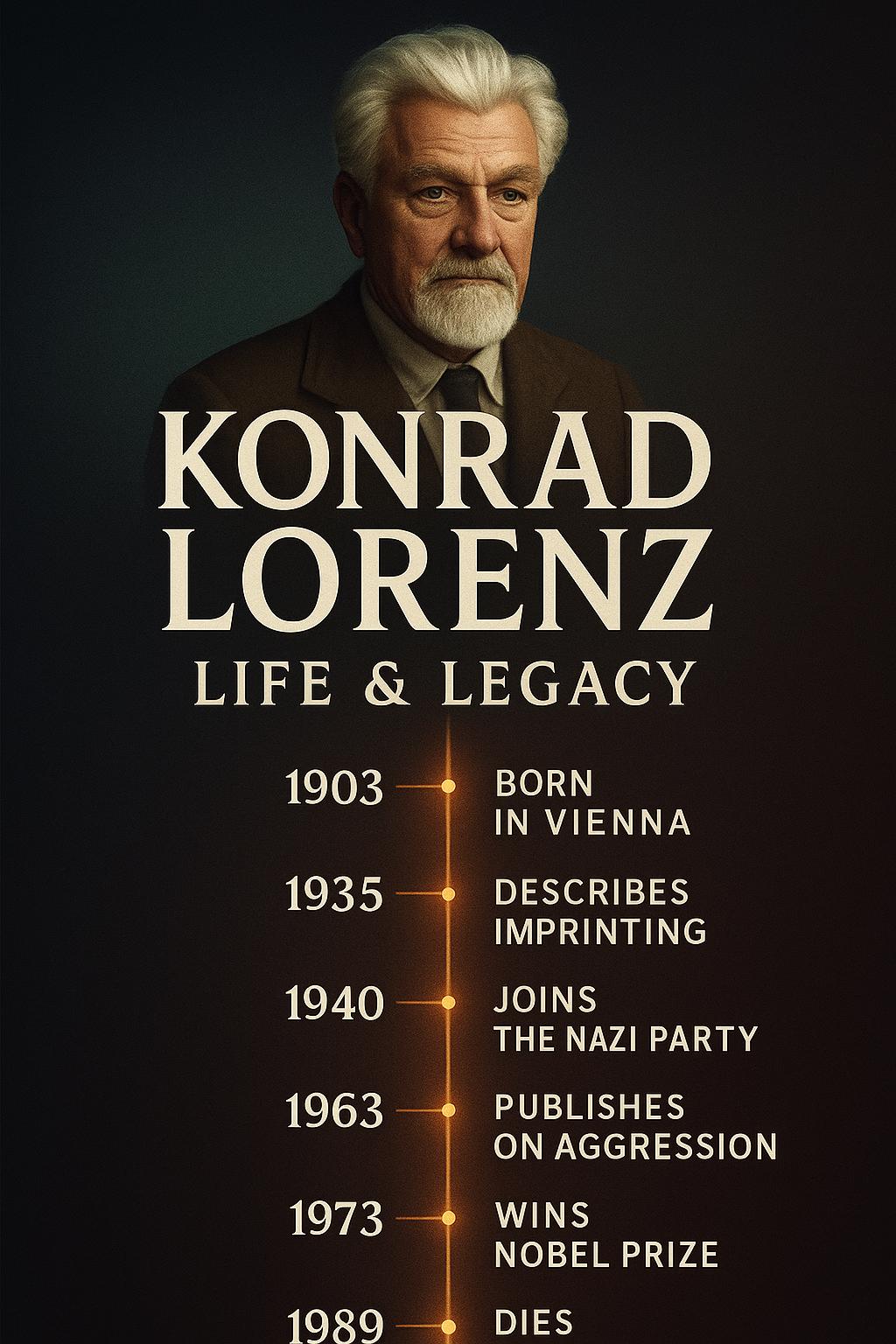

- Who: Konrad Zacharias Lorenz (1903–1989), Austrian zoologist, ornithologist and ethology pioneer.

- Field and era: Founding figure of twentieth-century ethology, the study of animal behaviour.

- Headline contributions: Experimental work on imprinting in birds, fixed action patterns and the ethological approach to instinct; co-recipient of the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

- Why he matters today: His ideas on instinct, bonding and aggression still shape debates in biology, psychology, education and environmental ethics—and his Nazi-era record forces us to ask who we celebrate in scientific history.

Early Life and Education of Konrad Lorenz

Childhood in Altenberg: a house full of animals

The Konrad Lorenz biography begins in Vienna in 1903, but the emotional centre of his childhood lay a short train ride away, in the small town of Altenberg on the Danube. His father, Adolf Lorenz, was a famous orthopaedic surgeon; his mother, Emma, was also a physician. Their large villa, with its fanciful architecture and spacious grounds, doubled as a private nature reserve for their youngest son.

From an early age, Lorenz filled the house and garden with animals: newts in jars, ducks in the pond, jackdaws hopping on the furniture. He later recalled that his parents were “supremely tolerant” of this chaos, as long as the animals did not completely overrun the dining room. A gifted observer, the boy spent hours watching how each creature moved, fed, fought and courted. Long before he knew the word “ethology”, he was rehearsing the role of an ethology pioneer.

Like many children who fall in love with animals, Lorenz first dreamed of becoming one of them. After reading Selma Lagerlöf’s tale The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, with its migrating wild geese, he imagined joining a flock and flying south. When that proved impossible, he settled for a more realistic plan: he would surround himself with birds and study them instead. The Konrad Lorenz biography is in part the story of how that childish fantasy hardened into a life’s work.

Medical school, zoology and the making of an ethology pioneer

Lorenz’s father, however, had more conventional ambitions. In 1922 he dispatched his son to New York to begin pre-medical studies at Columbia University, imagining a stable medical career rather than a life spent following geese. Lorenz dutifully went—but the call of animals and of European zoology was stronger. Within a year he was back in Vienna, enrolling in medical school there while quietly nurturing his real interests.

He completed his medical degree in 1928 and became an assistant at the Institute of Anatomy, dissecting human bodies by day and tending his menagerie by night. Not satisfied, he pursued a second doctorate in zoology, which he obtained in 1933. This dual training in medicine and zoology would later shape his distinctive approach: he treated behaviour patterns almost as if they were organs, with their own structure, development and evolutionary history.

During these Vienna years, the raw material for the Konrad Lorenz biography piled up in notebooks and improvised aviaries. He bred and cross-bred domestic and wild geese, watched hand-reared jackdaws form complicated social hierarchies, and compared the courtship rituals of different bird species. What fascinated him was not just what animals could learn, but the rigid, species-typical patterns that seemed to unfold as if programmed. Ethology, as he would help define it, would be the science of those patterns.

Konrad Lorenz biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

Discovering imprinting in ducklings and goslings

The episode that every Konrad Lorenz biography must tell involves a small duckling, a human boot and a moment that changed behavioural science. As Lorenz later recounted, he obtained a one-day-old duckling from a neighbour and found, to his “intense joy”, that the bird attached itself to him, following wherever he went. The duckling had “imprinted” on him: during a short, early “critical period”, it had fixed on the first moving object it saw as “mother”.

Lorenz turned this happy accident into systematic experiment. He arranged for some greylag goose eggs to hatch in an incubator, ensuring he—not the goose mother—was the first moving creature the goslings encountered. The results became iconic: a procession of goslings pattering after a bespectacled man, sometimes even scrambling into his lap or following him into a pond. If another person or even a moving object appeared first, the birds would imprint on that instead.

These observations crystallised Lorenz’s imprinting theory: in certain species, early experiences during a narrow developmental window permanently shape attachment and later behaviour. He adopted and expanded an older term, Prägung, to describe this rapid, apparently irreversible process. For Lorenz, imprinting became a model of how inherited structures and environmental triggers intertwine—a central theme in any serious Konrad Lorenz biography.

From hobby naturalist to architect of modern ethology

In 1936, Lorenz met the Dutch biologist Nikolaas Tinbergen at a conference on instinct. The two quickly realised they shared a similar vision: animal behaviour should be studied in natural or semi-natural settings, with careful observation of species-specific patterns, not only in laboratory boxes. Their collaboration, joined later by the bee researcher Karl von Frisch, would help establish ethology as a distinct discipline.

Together they developed key ethological concepts: the “fixed action pattern”, an instinctive sequence of behaviour triggered by a specific stimulus; the “innate releasing mechanism”, which filters the environment for those stimuli; and the idea of “supernormal stimuli”, exaggerated cues that elicit even stronger responses than natural ones. These ideas, taken for granted in many textbooks today, were once radical claims about the structure of instinct.

When later historians write a Konrad Lorenz biography, this period—roughly the late 1930s to early 1950s—appears as the creative core. Those were the years when small dramas in goose meadows became data for a new science, and when the word “ethology” moved from specialist circles into the broader story of twentieth-century biology.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Konrad Lorenz

King Solomon’s Ring and popular science with muddy boots

Lorenz did not confine his ethology pioneer role to academic journals. His 1949 book King Solomon’s Ring introduced a wide audience to his “companions” at Altenberg: jackdaws with strong opinions about human visitors, geese with jealous rivalries, and fish with intricate courtship dances. Written in a warm, anecdotal style, the book presented basic ethological concepts through vivid stories.

For many mid-century readers, this was their first encounter with ideas like imprinting, fixed action patterns and species-specific communication. The Konrad Lorenz biography cannot be separated from this public persona: the man who waded through ponds, notebook in hand, trying to think like a goose or a dog. In popular imagination, he became the avuncular “animal whisperer” of modern science.

On Aggression and the debate about human violence

In 1963, Lorenz published On Aggression, arguing that aggression in animals—and in humans—was not merely destructive but an evolved drive with adaptive functions. He suggested that in many species, ritualised aggression helps maintain social order without constant lethal conflict. Humans, he feared, had developed powerful weapons without inheriting equally strong inhibitions against killing their own kind.

The book arrived in a world shadowed by the Cold War and nuclear anxiety. Some readers seized on Lorenz’s argument as proof that war was “in our nature”, while others criticised him for oversimplifying complex social and political phenomena. Later commentators would debate whether his talk of “militant enthusiasm” and “discharge” of aggressive energy slid too easily from animal ethology into speculative human psychology.

Whatever one’s view, On Aggression ensured that any Konrad Lorenz biography must address not only his contributions to animal behaviour but also his controversial claims about human nature and conflict. It remains one of the most cited—and contested—popular science books of the twentieth century.

Fixed action patterns, supernormal stimuli and the ethology toolkit

Beyond specific books, Lorenz’s lasting scientific legacy lies in the conceptual toolbox he helped build for ethology and behavioural biology. His analyses of fixed action patterns—such as egg-rolling in geese or egg-retrieval in grebes—treated behavioural sequences as structured units that could be compared across species.

Experiments with Tinbergen on supernormal stimuli—like offering birds oversized eggs or exaggerated beak patterns—revealed that animals sometimes respond more strongly to artificial exaggerations than to natural cues. These findings anticipated later work in evolutionary psychology and neuroscience on how brains prioritise certain signals.

For students encountering animal behaviour history today, the Konrad Lorenz biography serves as an entry point into these foundational ideas, even as modern research refines and sometimes replaces his specific models.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Life at Altenberg as an open-air laboratory

Lorenz’s working style diverged sharply from the laboratory-centric approach of many psychologists of his time. He believed that to understand a species, you had to see it in its own Umwelt—its subjective world of stimuli and opportunities. Altenberg became his field station, with ponds, aviaries and kennels replacing white-walled labs.

He often lived among his animals: sleeping in rooms shared with jackdaws, paddling in ponds with geese, or letting dogs wander freely through his study. Students and visitors recalled a chaotic but strangely ordered household, where scientific discussion flowed over shared meals while a goose might peck inquisitively at a shoelace.

This immersive method is central to the Konrad Lorenz biography because it embodied his theoretical commitments. He wanted to see animals as whole beings in rich environments, not just as abstract subjects in controlled boxes. Critics later accused him of sentimental anthropomorphism, but his approach also inspired generations of field-oriented animal behaviour researchers.

Partnerships with Tinbergen and von Frisch

Lorenz’s collaborations with Nikolaas Tinbergen and Karl von Frisch show another side of his working style: he thrived in intellectual partnership. Tinbergen brought a more rigorous experimental discipline and a sceptical eye; von Frisch contributed dazzling work on honeybee communication. Together, their research on social behaviour patterns earned them the shared Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973.

In Nobel lectures and subsequent histories of ethology, these three are often presented as co-founders of a field. Yet their relationship was not always harmonious: they disagreed about the role of learning, about the proper balance of experiment and observation, and—especially in Lorenz’s case—about political responsibility during the Nazi era.

Any honest Konrad Lorenz biography must place him in this triangle of influence, rivalry and mutual respect, rather than casting him as a lone genius surrounded by birds.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Konrad Lorenz and Nazism: a dark chapter

For decades, many popular accounts glossed over a troubling part of the Konrad Lorenz biography: his membership in the Nazi Party and his participation in projects aligned with racial “hygiene”. Archival work later documented that Lorenz joined the Party in 1938, accepted a university chair under the regime and contributed to writings that echoed Nazi eugenic rhetoric.

During the war he served first as a psychologist examining so-called “German-Polish half-breeds” and then as a medic on the Eastern Front, where he was captured by Soviet forces and spent years as a prisoner of war. Later, Lorenz claimed that seeing transports of concentration-camp prisoners opened his eyes to the regime’s inhumanity. After 1945 he expressed regret for his political naivety, though critics have argued that his apologies were incomplete and sometimes self-protective.

The issue did not disappear with his death. In 2015, the University of Salzburg posthumously revoked an honorary doctorate, stating that Lorenz had misrepresented his Nazi-era activities. For readers today, the Konrad Lorenz biography is thus also a case study in how scientific achievement can coexist with, and be tainted by, moral compromise.

Group selection, “good of the species” and later critiques

Even within biology, Lorenz’s theoretical positions drew criticism. He often wrote as if natural selection acted directly “for the good of the species”, especially when discussing aggression and social behaviour. Later evolutionary biologists, including Richard Dawkins, attacked this view as incompatible with orthodox Darwinian theory, which sees selection primarily at the level of genes or individuals.

Some of his metaphors—the “hydraulic” model of drives, for instance—also seem dated today. Yet these critiques do not erase his role as an ethology pioneer; rather, they place the Konrad Lorenz biography within the normal, messy process of science, where influential models are later amended or overturned.

How later generations rewrote the Konrad Lorenz biography

One of the most revealing aspects of the Konrad Lorenz biography is how it has been revised over time. Early tributes portrayed him almost exclusively as a kindly naturalist and Nobel laureate. Later historians and journalists dug into wartime archives, confronting the Nazi-era writings and questioning earlier narratives that had treated his political involvement as a youthful mistake.

That shift matters. It reminds readers that biographies, especially of scientists, are not static portraits but evolving arguments about what—and whom—science chooses to celebrate.

Impact on Ethology and on Wider Society

From geese to classrooms: imprinting in textbooks

Long after the original experiments in Austrian meadows, Lorenz’s work on imprinting still appears in school and university curricula around the world. Teaching materials explain how a gosling, during a brief critical period, will follow the first moving figure it sees—whether that is its mother, a dog or a human in a lab coat. The goose line trotting behind Lorenz has become a stock image in psychology and biology textbooks.

Guides for teachers draw directly on this ethology pioneer’s work to illustrate broader principles of learning, attachment and development. The Konrad Lorenz biography thus lives on not only in archives and scholarly monographs but in lesson plans, diagrams and classroom anecdotes that introduce new generations to the idea that early experiences can leave indelible marks.

Environmental warnings and the fate of civilisation

In his later years, Lorenz’s concerns shifted increasingly toward the ecological and social consequences of modern civilisation. He warned that rapid urbanisation, technological change and mass culture were eroding the psychological and biological structures that had sustained human communities.

These themes, explored in essays and popular books, often blended sharp observation with generational pessimism. Critics accused him of romanticising a pre-industrial past and over-generalising from animal behaviour to complex human societies. Still, for many readers, this ecological strand adds an unexpected dimension to the Konrad Lorenz biography: the goose-herding Nobel laureate as a reluctant prophet of environmental decline.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Family life, humour and stubbornness

Away from the conference podium, Lorenz inhabited a dense web of family ties and long friendships. He married his childhood companion, Margarethe Gebhardt, a gynaecologist, and they raised three children, all of whom grew up surrounded by animals. Visitors often described the household as a whirl of dogs, geese, students and scientific gossip.

Friends and colleagues recall his booming laughter, love of practical jokes and willingness to launch into impromptu lectures at the dinner table. They also note his stubbornness: once he reached a judgment—about a colleague, a theory or a political issue—he could cling to it tenaciously. This mix of warmth and rigidity threads through the Konrad Lorenz biography and may help explain both his scientific persistence and his political misjudgements.

Dogs, geese and the moral status of animals

Lorenz’s popular writings reveal a deep emotional attachment to his animals, especially to dogs and geese, whom he treated as individual personalities rather than interchangeable specimens. In books like Man Meets Dog, he wrote of canine loyalty and companionship in ways that blurred the boundary between scientific observation and affection.

This personal bond fed into his broader views on animal welfare and conservation. Long before “animal rights” entered mainstream discourse, he argued that humans had moral obligations to other species and warned about the spiritual costs of treating animals merely as tools or resources. In that sense, the Konrad Lorenz biography is also part of the longer story of how modern science gradually re-evaluated the place of animals in human moral life.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Konrad Lorenz

Nobel Prize, honours and changing reputations

The high point of Lorenz’s public career came in 1973, when he, Tinbergen and von Frisch received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for their discoveries concerning organization and elicitation of individual and social behaviour patterns”. The award cemented his status as a founding father of ethology and brought his name into newspapers around the world.

In the years that followed, he accumulated honours from academies and universities, directed the Max Planck Institute for Behavioural Physiology and continued to publish books for both experts and general readers. Yet as his scientific reputation blossomed, shadows from his past slowly emerged, complicating the narrative.

He died in 1989 at his beloved Altenberg home, aged eighty-five. A detailed New York Times obituary of Lorenz balanced praise for his scientific innovations with acknowledgment of his political failings, setting the tone for many later accounts of the Konrad Lorenz biography.

Return to Altenberg and the Green movement

In his final decade, Lorenz became an unlikely figurehead for Austria’s emerging environmental movement. He supported protests against a hydroelectric power plant at Hainburg on the Danube, lending his name and presence to a broad coalition of activists trying to protect floodplain forests.

This late-life engagement with environmental politics added yet another layer to the Konrad Lorenz biography. The same man who had once embraced a regime that instrumentalised “nature” for racial ideology now stood with campaigners seeking to defend ecosystems from industrial development. For admirers and critics alike, that arc remains difficult to interpret in simple moral terms.

The Lasting Legacy of Konrad Lorenz biography

Why his ethology still matters

More than three decades after his death, the scientific legacy of this ethology pioneer is still very much alive. Some of his models have been revised or replaced, and his enthusiasm for group-selection explanations now looks like a historical curiosity. Yet core insights of the Konrad Lorenz biography—the importance of species-specific behaviour patterns, the power of early experiences, and the value of studying animals in their natural contexts—remain embedded in modern animal behaviour research.

Neuroscience and behavioural ecology today ask questions Lorenz could scarcely have imagined, using brain imaging, genetic tools and computational models. Still, many of those projects implicitly follow the path he helped clear: watching animals carefully, asking what their behaviour reveals about adaptation and evolution, and taking their subjective worlds seriously.

Reading a complicated life in the twenty-first century

For contemporary readers, the Konrad Lorenz biography offers both inspiration and warning. His best work shows how curiosity, patient observation and imaginative theorising can open a new window onto the lives of other species. His worst choices show how scientific authority can be entangled with destructive ideologies—and how long it can take to fully reckon with that entanglement.

Understanding this Konrad Lorenz biography helps us understand something larger about modern science. It reminds us that discoveries do not float free from their historical context; they are made by people shaped by their times, their prejudices and their courage. If we want a more honest science—one that honours animals without romanticising them, and faces human aggression without excusing it—we have to hold both the geese and the ghosts in view.

For a deeper historical and ornithological perspective on his life and work, readers can explore the memorial article “In Memoriam: Konrad Lorenz, 1903–1989”, published in the journal The Auk and hosted by the University of South Florida.

Frequently Asked Questions about Konrad Lorenz biography

Below are brief answers to some common questions readers ask when first encountering Konrad Lorenz and his work.

Q1: Who was Konrad Lorenz and why is he considered a pioneer of ethology?

Q2: What is imprinting in the context of the Konrad Lorenz biography?

Q3: Did Konrad Lorenz only study birds?

Q4: Why is Konrad Lorenz’s connection to Nazism controversial?

Q5: How has modern science built on or revised Lorenz’s ideas?

Q6: Where should I start if I want to read more about Konrad Lorenz?