A longform, original feature on the science, ethics, and enduring legacy of Jonas Salk’s work—crafted for readers and editors who value depth, clarity, and public-minded journalism.

What followed was more than a scientific milestone. The Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C8) rewired how institutions and communities cooperate when life and trust are on the line. It also reframed a technical debate—live-attenuated versus inactivated vaccines—into a pragmatic question: Which tool, under which conditions, best protects real people living real lives?

The Road to the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine

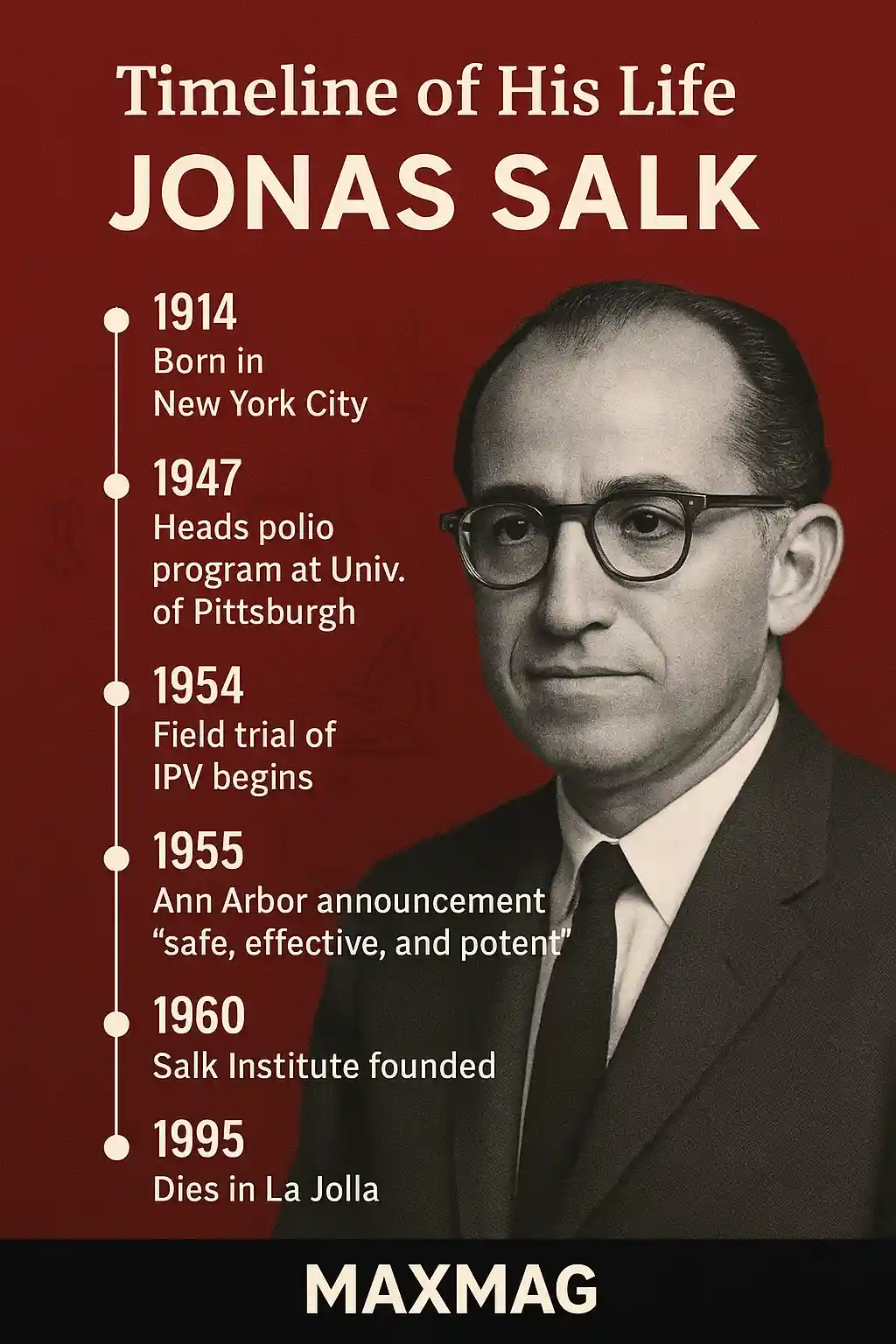

Jonas Salk’s formative years—NYU medical school, wartime influenza research, and mentorship under Thomas Francis Jr.—sharpened a central hypothesis: a pathogen’s “signature” might be presented to the immune system without letting the pathogen replicate. In practice, this meant growing poliovirus in non-neural tissue cultures and using formalin to inactivate it, preserving antigenic structure while removing replicative capacity. That tradeoff, the beating heart of the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C9), demanded exquisite control over time, temperature, and concentration.

Funding from the March of Dimes transformed dimes and quarters into cell culture rooms, glassware, technicians, and statistical support. Salk’s Pittsburgh group became an engine for methodical iteration: grow, inactivate, assay; adjust, repeat, confirm. At each turn, the question was unchanged—could a killed-virus preparation reliably produce neutralizing antibodies? Positive animal data encouraged cautious optimism, but the verdict had to be earned in humans, not inferred from the bench. By 1953, the program was poised to test whether the promise of the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C10) would survive first contact with the complexities of public life.

Two additional ingredients mattered: systems thinking and humility. Salk and colleagues did not imagine the lab as a silo. They built early bridges to manufacturers, public health departments, and biostatisticians—an ecosystem able to scale if the signal was strong. That foresight would prove decisive when national trials began and when the first production lots of the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C11) rolled off industrial lines.

Field Trials and the Public Unveiling of the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine

In 1954–55, under Thomas Francis Jr.’s direction at the University of Michigan, more than a million American children—“Polio Pioneers”—entered a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. Endpoints were clinically meaningful: paralytic disease, not merely serologic titers. The trial’s scale conferred power to detect effects across age bands and regions, and its architecture insulated results from bias. When Francis announced the verdict on April 12, 1955—“safe, effective, and potent”—the evidence base for the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C12) was both massive and methodologically sound.

Then came translation: supply chains, clinic workflows, refrigeration, documentation, and communication with parents. School gymnasiums turned into inoculation centers. Nurses and pediatricians became the human interface of the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C13), answering practical questions and defusing rumor. In this phase, logistics carried as much moral weight as immunology; a well-run clinic was a form of public argument in favor of science done carefully.

The triumph was tested almost immediately. A manufacturing failure at Cutter Laboratories led to incompletely inactivated lots, causing paralysis and deaths. Production paused; oversight tightened; standards were rewritten. Crucially, independent panels distinguished a process failure from a conceptual one, allowing properly produced lots of the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C14) to resume while quality systems were rebuilt around sterner assumptions.

What the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine Changed

The first change was visible on hospital wards: fewer iron lungs, fewer isolation rooms, fewer families staring at the ceiling through sleepless nights. The second change was infrastructural: a collaborative template connecting philanthropy, academia, government, and industry. The third was philosophical: proof that an inactivated preparation—the core principle of the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C15)—could deliver durable, real-world protection at population scale.

Strategy matured alongside success. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV) offered mucosal immunity and ease of use, especially in mass campaigns; inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) provided a robust safety profile and fit routine schedules in high-resource settings. Over decades, programs blended tools—often beginning with OPV in outbreak control and pivoting to IPV—descendants of the original Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C16)—to harden population immunity and reduce risks of vaccine-derived transmission.

Culture shifted too. When new pathogens loom, editors and policymakers reach for precedents to explain what “safe and effective” should look like. The Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C17) became a touchstone: announce results only when data can withstand scrutiny, coordinate manufacturing with regulation, and build feedback loops that can detect and correct error without losing public confidence.

Safety, Trust, and the Work After the Headlines

Post-Cutter reforms hardened modern expectations: validated inactivation curves, redundant filtration steps, lot genealogy, and adverse-event reporting that treats every anomaly as a teachable signal. In ethical terms, the system learned to behave as though each dose were destined for one’s own child. The same posture underpins contemporary derivatives of the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C18), which are manufactured under current Good Manufacturing Practices and monitored by independent regulators.

Science Communication, Then and Now

Francis’s plain declaration—“safe, effective, and potent”—worked because trial architecture pre-committed to meaningful endpoints and full public scrutiny. Today, the channels have changed, but the grammar of trust has not: pre-registration, independent review, transparent data, and continuous post-marketing surveillance. When journalists contextualize new vaccines, they often cite the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C19) because it set a durable benchmark for how to present evidence without theatrics.

Early Lessons for Modern Readiness from the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine

Modern immunization campaigns inherit three working rules: don’t skip steps, show your work, and stay present long after rollout. The agencies, laboratories, and manufacturers that stewarded the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine (C20) modeled that posture, earning permission from the public to keep doing ambitious things. The result was not a one-time victory but a maintenance plan for confidence.

The Human Face of a Curve: Living After the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine

On a graph, success appears as a line that falls. In homes and neighborhoods, it feels like a summer without whispered dread, a school without the rumor of quarantine, a child who never sees the inside of an iron lung. That is the everyday meaning of technical progress, and it explains why the memory of the Jonas Salk Polio Vaccine lingers decades after the crisis faded.

How Salk Worked: People, Systems, and the Long Arc of Proof

The craft behind the breakthrough was cumulative—serotype mapping, cell-culture technique, neutralization assays, animal challenge models, and the choreography of a nationwide trial. Salk’s gift was to assemble these moving parts into a system and to keep the focus on questions that mattered: Can this method be safe at industrial scale? Can clinics execute it without heroics? Can the evidence survive skeptical audit? The answers, earned step by measured step, made the difference.

Ethics, Patents, and the Public Good

Asked who owned the vaccine, Salk replied, “Could you patent the sun?” The remark crystallized a broader stance: publicly funded science should be accessible, and lifesaving tools should not be gated by ownership if that would slow adoption. He did not mistake idealism for logistics; he demanded consistency from manufacturers and welcomed stronger oversight after Cutter. In effect, Salk described a social contract: society invests in science; science reduces suffering; institutions prove worthy of trust by telling the truth and fixing problems in public.

Salk Institute: Architecture as Scientific Argument

Louis Kahn’s design in La Jolla translates Salk’s values into form—clarity, light, and the quiet insistence on conversation. The runnel that draws the eye to the Pacific is not decoration; it is an axis of intent, a line that says ideas should move and meet. Although today’s research spans fields far from poliovirus, the building remains a working metaphor for the habits that made the original breakthrough possible.

Three High-Value Additions (Deepening the Picture)

Trial Design, Power, and Evidence Integrity

Randomization removed allocation bias; placebo control filtered background noise; double-blinding minimized expectation effects. Surveillance sought every suspected case, not just those near trial centers. Endpoints were pre-declared, and the analysis plan was robust to post-hoc fishing. The result was an evidentiary spine that would satisfy today’s best practices—an enduring reason the 1955 announcement convinced both scientists and citizens.

Manufacturing After Cutter: How Quality Systems Evolved

The aftermath of the Cutter incident was formative for modern biomanufacturing. In-process controls moved upstream; sterility assurance and statistical sampling were re-engineered; lot-release protocols demanded independent confirmation. The lesson has aged well: safety is a process, not a property. Contemporary IPV production reflects that discipline daily.

Global Eradication: The “Switch,” Sequencing, and IPV’s Modern Role

As wild poliovirus receded, rare vaccine-derived outbreaks required adaptation. Programs adjusted OPV formulations, expanded environmental surveillance, and integrated IPV boosters to strengthen population immunity. Genomic sequencing now maps transmission chains in near-real time, converting molecular fingerprints into field action. The eradication endgame is a moving target, but the values that Salk modeled—rigor, transparency, and humility—remain fixed coordinates.

Famous Quotes by Jonas Salk

“Could you patent the sun?” captures Salk’s ethics in seven words. “Intuition will tell the thinking mind where to look next” describes the dialogue between creativity and method. “The reward for work well done is the opportunity to do more” reframes success as responsibility. And “Hope lies in dreams, in imagination, and in the courage of those who dare to make dreams into reality” explains why a vaccine could become a cultural symbol rather than a mere technical achievement.

Further Reading from Trusted U.S. Sources

For current guidance on poliovirus, transmission, and vaccination schedules, see the CDC’s polio overview and vaccine recommendations. For historical context on laboratory milestones, field trials, and the policy environment, explore the NIH History Office’s materials on polio and vaccine development. Both resources complement this feature with authoritative detail.

Conclusion: Science in the Key of Responsibility

Every breakthrough is a negotiation with the future. We build instruments and institutions that will outlast us and hope we have tuned them well. Salk’s work shows what it means to tune for the public good: define the question clearly, build the method safely, test it under real conditions, tell the truth about the results, and improve the system when it falters. That is how fear bends toward confidence and emergency becomes routine care.