The story told by any serious Jennifer Doudna biography begins with a deceptively simple question: what happens when a quiet, RNA-obsessed biochemist helps give humanity the power to rewrite life’s code? Long before she stood on a Stockholm stage accepting the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for turning a bacterial defence trick into the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing tool, Jennifer Doudna was a bookish child in Hawaii, more at home in the library than on the beach. Her journey from that remote island school to the centre of a global ethical debate is one of the defining scientific narratives of the twenty-first century.

The Jennifer Doudna biography is, at heart, a story about curiosity colliding with responsibility. It traces how a lifelong fascination with RNA and molecular structure led to a technology that can correct faulty genes, alter crops and, potentially, reshape ecosystems. But it also follows a scientist forced into the public square to argue about where the limits of gene editing should lie. For readers with no specialist background in biology or genetics, this is not just a tale of lab work and prizes; it is a window into how modern science evolves, who gets to steer it and how society decides what is acceptable when we finally hold evolution’s tools in our own hands.

Jennifer Doudna biography at a glance

- Who: Jennifer A. Doudna, American biochemist and CRISPR pioneer.

- Field and era: Molecular biology and gene editing, late 20th century to 21st century biology.

- Headline contribution: Co-developer of CRISPR-Cas9 as a programmable genome-editing tool, awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Emmanuelle Charpentier.

- Why she matters today: Central figure in debates on gene editing history, bioethics and how far humanity should go in redesigning living organisms.

These snapshots capture only the surface of the Jennifer Doudna biography; the deeper story lies in the blend of meticulous bench science, fierce patent disputes, sleepless nights over embryo editing and a constant effort to explain CRISPR to a world that is still deciding what it thinks about rewriting DNA.

Early Life and Education of Jennifer Doudna

From Washington, D.C. to Hawaii: childhood chapters in the Jennifer Doudna biography

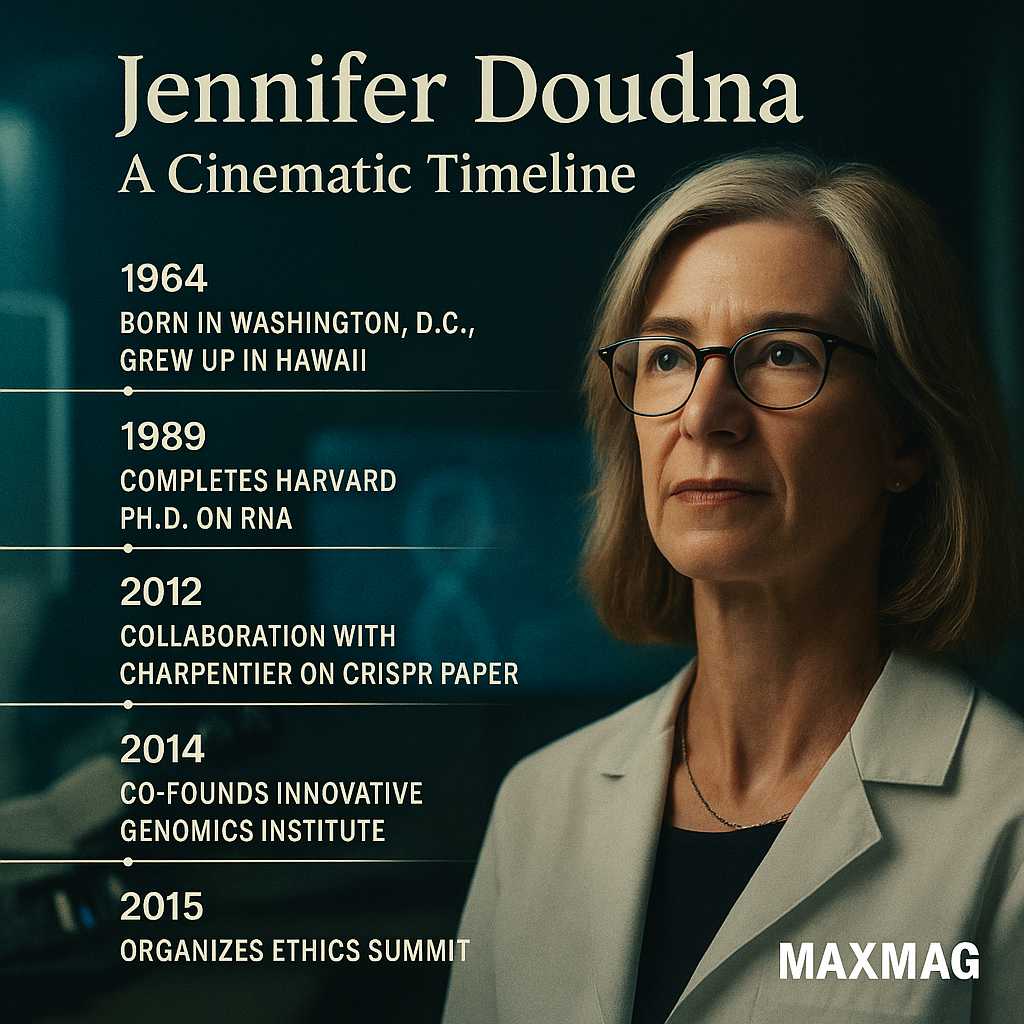

Jennifer Doudna was born in Washington, D.C., in 1964, but the landscape that shaped her imagination was thousands of kilometres away, on the Big Island of Hawaii. Her father, a literature professor, and her mother, a stay-at-home parent who later returned to education, moved the family to Hilo when she was a young child. The contrast between lush tropical forests and volcanic rock, between a small, somewhat isolated town and the vast Pacific, gave this future CRISPR pioneer an early sense that the natural world was full of hidden patterns waiting to be decoded.

For any Jennifer Doudna biography, Hawaii is the emotional centre of the early narrative. She has often described feeling slightly out of place at school—one of the few white mainland kids in her class—but utterly at home wandering through tide pools and reading books about science. A high school teacher placed James Watson’s The Double Helix on her desk, and the backstage view of DNA discovery, with all its rivalries and rough edges, made laboratory work seem less abstract and more like a human drama she might join.

Discovering chemistry and the allure of RNA

Leaving Hawaii for Pomona College in California, Doudna gravitated towards chemistry rather than medicine, drawn to the elegance of molecules and the satisfaction of solving problems at the atomic scale. In an era when many young women were quietly discouraged from careers in physical sciences, mentors who took her ambition seriously became crucial characters in the early Jennifer Doudna biography. She learned that the laboratory could be a place where curiosity and rigour coexisted, and where a shy student could speak most clearly through her experiments.

Graduate work at Harvard put her under the supervision of Jack Szostak, a future Nobel laureate and a leading figure in RNA research. There, she plunged into the world of ribozymes—RNA molecules that behave not just as messengers but as catalysts, performing tasks traditionally assigned to proteins. For readers new to molecular biology, ribozymes can be thought of as Swiss-army knives made of genetic material, able to both carry information and perform work. This duality fascinated her and set a pattern: whenever a biological molecule broke the “rules” she thought she understood, she leaned in.

Jennifer Doudna biography and the Birth of CRISPR Gene Editing

First encounters with RNA, structure and a bacterial mystery

After postdoctoral work with Thomas Cech—another RNA legend—Doudna joined the faculty at Yale and later moved to the University of California, Berkeley, where she became a professor of biochemistry, molecular and cell biology and chemistry, holding the Li Ka Shing Chancellor’s Chair and working as a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. Her speciality remained structural biology: using high-powered X-rays to map the three-dimensional forms of RNA and protein complexes. To a non-specialist, this work can sound esoteric, but its purpose is intuitive: if you want to know what a tool can do, you first need to know its shape.

Around 2005, a new puzzle crossed her desk: short, repeated DNA sequences in bacteria, interspersed with odd “spacer” segments taken from viruses. This pattern, known as CRISPR, had been noticed by microbiologists but not fully understood. Working with geobiologist Jill Banfield and other colleagues, Doudna began to consider whether this strange pattern might represent a kind of immune memory, a molecular scrapbook of infections that allowed bacteria to recognise and attack their viral enemies more quickly the second time around.

A chance meeting that changed the Jennifer Doudna biography

The pivotal scene in the Jennifer Doudna biography takes place not in a lab, but on the cobbled streets of Old San Juan, Puerto Rico. In 2011, at a microbiology conference, Doudna met Emmanuelle Charpentier, a French microbiologist studying a flesh-eating bacterium, Streptococcus pyogenes. Charpentier had been tracking a mysterious protein, Cas9, that worked with the CRISPR system to cut viral DNA. As the two scientists walked and talked, they realised they were holding different pieces of the same puzzle.

Their collaboration, and the small international team they built around it, produced a now-famous 2012 paper in Science. The work showed that CRISPR could be re-engineered into a simple, programmable tool: by providing a short piece of guide RNA, scientists could direct the Cas9 enzyme to snip DNA at almost any desired sequence. To someone unfamiliar with gene editing history, the breakthrough is easiest to imagine as moving from using scissors at random in a long text to having a precise “find and replace” function for the genetic code.

Almost overnight, Doudna found herself recast from a respected RNA specialist into a global CRISPR pioneer. Laboratories that had struggled for years with slow, expensive methods like zinc-finger nucleases or TALENs suddenly had access to a cheaper, faster and more precise system. Within months, CRISPR-Cas9 was being used to tweak genes in mice, plants and human cells, opening a new chapter for 21st century biology.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Jennifer Doudna

Reimagining CRISPR-Cas9 as a programmable tool

The technical heart of Doudna’s contribution lies in turning a bacterial defence trick into a general-purpose tool. Before CRISPR, genome editing was like repairing a book using blunt scissors, glue and guesswork. Her team’s contribution was to connect a highly specific “search function” (the guide RNA) to a pair of molecular scissors (Cas9), creating a system that could be targeted to almost any stretch of DNA simply by changing the guide sequence. For many biologists, this was the moment when gene editing stopped being an exotic craft and became a standard laboratory method.

Beyond the headline CRISPR-Cas9 technology, Doudna’s lab has continued to explore new CRISPR systems, variants that act more like scalpels than scissors, and tools that can change single DNA letters without fully cutting the strand. These refinements are less visible to the public than the original breakthrough, but they reflect a deepening CRISPR pioneer legacy: moving from crude edits towards precision surgery on the genome.

A Crack in Creation and explaining CRISPR to the public

One of the striking aspects of the Jennifer Doudna biography is how quickly she recognised that CRISPR raised questions far beyond the lab bench. Together with her former student Samuel Sternberg, she co-authored A Crack in Creation, a book that mixes scientific explanation with personal reflection on the unthinkable power to control evolution. The book attempts to do for gene editing what earlier popular science works did for cosmology or quantum mechanics: make a complex field emotionally and intellectually legible to general readers.

For those seeking a more formal overview of her work and honours, a UC Berkeley College of Chemistry biography of Jennifer Doudna pulls together her roles as professor, Nobel laureate and leader in molecular and cell biology. It places her alongside other major figures in modern science, underlining how quickly CRISPR-Cas9 moved from a speculative idea to a centrepiece of contemporary molecular biology.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Running a collaborative, interdisciplinary lab

Inside the laboratory, colleagues describe Doudna’s style as both demanding and unusually collaborative. Rather than treating the lab as a hierarchy, she has cultivated what she calls a “supportive environment,” where senior members mentor junior researchers and ideas cross boundaries between chemistry, structural biology, microbiology and computational work. This approach matters because CRISPR research moves so quickly that no single discipline can keep up on its own.

Her methods reflect the broader trend in 21st century biology towards team-based discovery. In the Jennifer Doudna biography, the heroes are rarely lone geniuses; they are postdocs who pack up their lives to move across continents, graduate students who re-run a discouraging experiment a hundred times and technicians who keep the lab’s complex machinery humming. Doudna’s willingness to share credit, and her emphasis on mentoring, has become part of her legacy as much as any single paper.

Mentors, mentees and the wider CRISPR pioneer network

Doudna often credits her own mentors—figures like Jack Szostak and Tom Cech—with shaping her scientific instincts. In turn, she has become a mentor to a generation of younger scientists who now lead their own laboratories or biotech start-ups. Many of them carry part of the CRISPR pioneer story into areas ranging from rare disease therapies to agriculture and climate-focused genome engineering.

The web of collaborations around her includes clinicians, ethicists, plant biologists and computer scientists. This network has been essential in translating the abstract chemistry of CRISPR into actual treatments and real-world applications, and it shows how the Jennifer Doudna biography is woven deeply into the broader fabric of gene editing history.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Patent battles and the history of gene editing rivalries

No modern scientific success story is complete without a dispute over credit and patents, and the Jennifer Doudna biography is no exception. After Doudna and Charpentier’s 2012 paper, a parallel stream of work led by Feng Zhang at the Broad Institute demonstrated CRISPR-Cas9 in mammalian cells. The result was a complex, years-long legal battle over who owned key patents on CRISPR technology and how far their claims extended.

For non-lawyers, the details are dizzying: competing applications, interference proceedings and appeals in multiple jurisdictions. What matters for understanding Doudna’s story is that these disputes highlighted tension between open scientific collaboration and the realities of commercialisation. Gene editing history, like the history of earlier technologies, is now entangled with high-stakes intellectual property, venture capital and billion-dollar biotech firms.

The ethics of editing embryos

Perhaps the most emotionally charged chapter in the Jennifer Doudna biography revolves around human embryos. In 2015, as experiments on editing human embryos began appearing in the literature, Doudna joined other prominent scientists in calling for a temporary pause on clinical use of germline gene editing—the kind that would pass changes on to future generations—until safety and ethical questions had been more fully examined.

Her own views have evolved over time. Initially, she described waking from a nightmare in which someone approached her in a Nazi uniform asking her to explain CRISPR, a sign of how heavily the potential misuse of the technology weighed on her. Later, as she heard from families facing devastating genetic diseases, her language shifted from fear to a more nuanced balance of caution and hope. This tension—between the promise of curing disease and the risk of new inequalities or abuses— is one of the core ethical threads in any honest Jennifer Doudna biography.

Impact on Gene Editing and on Wider Society

Transforming 21st century biology and medicine

In practical terms, CRISPR-Cas9 has become a standard tool for laboratories across the world. It is used to knock out genes in mice to study disease, to engineer immune cells that attack cancer and to design viruses that can carry corrective genetic instructions into human tissues. Clinical trials are now under way for conditions ranging from sickle cell disease to certain forms of inherited blindness, and Doudna’s role in creating the underlying technology makes her a central figure in these emerging therapies.

An influential New York Times profile of Jennifer Doudna and CRISPR-Cas9 helped bring this revolution to a mainstream audience, portraying her as a scientist suddenly thrust into the spotlight as “a pioneer who helped simplify genome editing.” For many readers, that article was their first introduction to the idea that changing DNA in living organisms might soon become routine.

From crops to climate: CRISPR beyond the clinic

Doudna’s influence extends well beyond human medicine. Through the Innovative Genomics Institute, which she helped found and now leads, she has championed the use of CRISPR to build disease-resistant crops, reduce the environmental impact of agriculture and explore ways gene editing might help address climate-related challenges, such as engineering plants or microbes that capture more carbon.

These projects illustrate one of the key secondary themes of the Jennifer Doudna biography: the idea that genome editing is not a narrow medical tool but a platform technology with implications for food security, bioenergy and environmental stewardship. They also raise difficult questions about who will benefit from CRISPR-enabled crops and whether small farmers will have access to the resulting innovations.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Doubts, pressure and living at the center of a revolution

Despite her public role, Doudna is by most accounts introverted and somewhat reserved, more comfortable in a quiet office than in a television studio. The pace of the CRISPR revolution forced her to become a public figure almost against her instincts. Interviews show a recurring pattern: a careful, precise scientist trying to explain breathtaking possibilities without overselling them, and acknowledging the unease that many people feel about redesigning life.

The Jennifer Doudna biography is filled with moments of self-doubt: fears that CRISPR might spiral out of control, that she might not be doing enough to address ethical concerns, or that the technology could deepen existing social inequalities if only wealthy patients or nations could access it. These doubts did not paralyse her; instead, they pushed her into roles—public speaker, policy advocate, ethics organiser—that she might never have sought otherwise.

Family life and life outside the lab

Away from the lecture circuit and the bench, Doudna is a wife and mother, trying to balance the demands of a globally significant research programme with the everyday tasks of parenting and partnership. She has spoken about the importance of carving out time for family, and of showing young scientists—especially women—that it is possible to pursue ambitious research careers without giving up a personal life.

These quieter scenes matter because they round out the Jennifer Doudna biography, reminding readers that the person making decisions about gene editing is also someone who worries about school schedules, ageing parents and the small, private dramas that run alongside scientific breakthroughs.

Later Years and Ongoing Chapter of Jennifer Doudna

Innovative Genomics Institute and new frontiers

In recent years, Doudna’s work has increasingly focused on translating CRISPR from laboratory concept to practical tool. As founder and chair of the Innovative Genomics Institute in Berkeley, she oversees programmes that push genome editing into clinical trials, agricultural test plots and even microbiome engineering projects that aim to reshape entire microbial communities for health and climate benefits.

At the same time, she continues to lead the Doudna Lab and to publish on new CRISPR systems and RNA- guided mechanisms. The lab’s website reads like a running logbook of 21st century biology, filled with structural models, new assays and unconventional approaches to molecular problems. In this phase of the Jennifer Doudna biography, the focus is less on single, headline-grabbing breakthroughs and more on building durable tools and institutions.

From Nobel Prize to next questions

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, shared with Emmanuelle Charpentier, could have been an endpoint. Instead, Doudna has treated it as a milestone in a longer journey. Recognition has increased the pressure on her to speak for the field and to think about what comes after CRISPR-Cas9. As newer gene editing technologies emerge—base editors, prime editors and beyond—she is again at the intersection of scientific detail and societal implication.

This period of the Jennifer Doudna biography is characterised by questions rather than answers: How can gene editing be made safer and more precise? How should regulators weigh risks and benefits? How can global governance systems keep pace with technologies that can be deployed in any modestly equipped lab around the world?

The Lasting Legacy of Jennifer Doudna biography

How the Jennifer Doudna biography reshapes our view of scientists

One of the most striking aspects of the Jennifer Doudna biography is how it challenges clichés about what a scientist looks like and how science advances. Doudna is not a lone genius in a white coat, but part of a dense network of collaborators, critics and competitors. Her story shows how breakthroughs emerge from decades of basic research, the patient mapping of obscure molecules and the willingness to follow a puzzling result into unfamiliar territory.

For young researchers and students, the Jennifer Doudna biography offers a different kind of role model: a scientist who is both deeply technical and unafraid to admit uncertainty, who believes in the power of molecular tools but also insists on public debate about how they are used. It suggests that being a “CRISPR pioneer” in 21st century biology means not just inventing new techniques but helping society learn how to live with them.

More broadly, the Jennifer Doudna biography illustrates how individual lives intersect with vast social and technological shifts. Her journey from curious girl in Hawaii to Nobel laureate grappling with the ethics of editing human embryos mirrors our collective journey into a world where genomes can be rewritten. Understanding that story helps us understand the larger question that hangs over gene editing history: not just what we can do with CRISPR, but what we should do—and who gets to decide.

In that sense, returning to the details of the Jennifer Doudna biography is not an exercise in hero-worship; it is a way to think more clearly about how power, responsibility and imagination are distributed in modern science, and about the choices that will shape the future of life on Earth.

Frequently Asked Questions about Jennifer Doudna biography

Q1: Who is Jennifer Doudna, and why is she important in modern biology?

Q2: What is CRISPR-Cas9, in simple terms?

Q3: How did the Jennifer Doudna biography become linked to ethical debates about gene editing?

Q4: What major awards has Jennifer Doudna received for her work?

Q4: What major awards has Jennifer Doudna received for her work?

Q6: How does the Jennifer Doudna biography inspire future scientists and students?