At first light along Lake Tanganyika, hornbills call from the canopy and the understory shifts with a life you can hear before you see. A young researcher settles into the brush, not to trap or test but to watch. She writes in longhand, names the individuals she meets, and refuses the clinical distance that mid-century science demanded. The result is less a single breakthrough than a sustained act of witness that altered what we think we know about intelligence, culture, and responsibility. This is the story of how patient observation became a public ethic—and how that ethic built a movement.

The stakes are not only historical. Forest corridors shrink; rainfall becomes less predictable; trafficking networks adapt as fast as the rangers who pursue them. And yet, communities keep replanting hillsides, students keep organizing local projects, and an institute started from a tent on a Tanzanian lakeshore keeps adding chapters to a story still unfolding. The Jane Goodall biography is therefore not a museum piece but a living argument: about evidence, about empathy, and about how science and society can change each other.

Where the Jane Goodall biography truly begins: henhouse, horizon, and stubborn curiosity

It is convenient to begin at Gombe with tool-use and termite fishing, but the Jane Goodall biography starts much earlier in Bournemouth, with a child who hides in a henhouse to discover how eggs are laid. The point isn’t cuteness; it’s method. Stillness. Waiting. Proof over hearsay. That early stubbornness—which some might have called daydreaming—became a discipline long before it had a name.

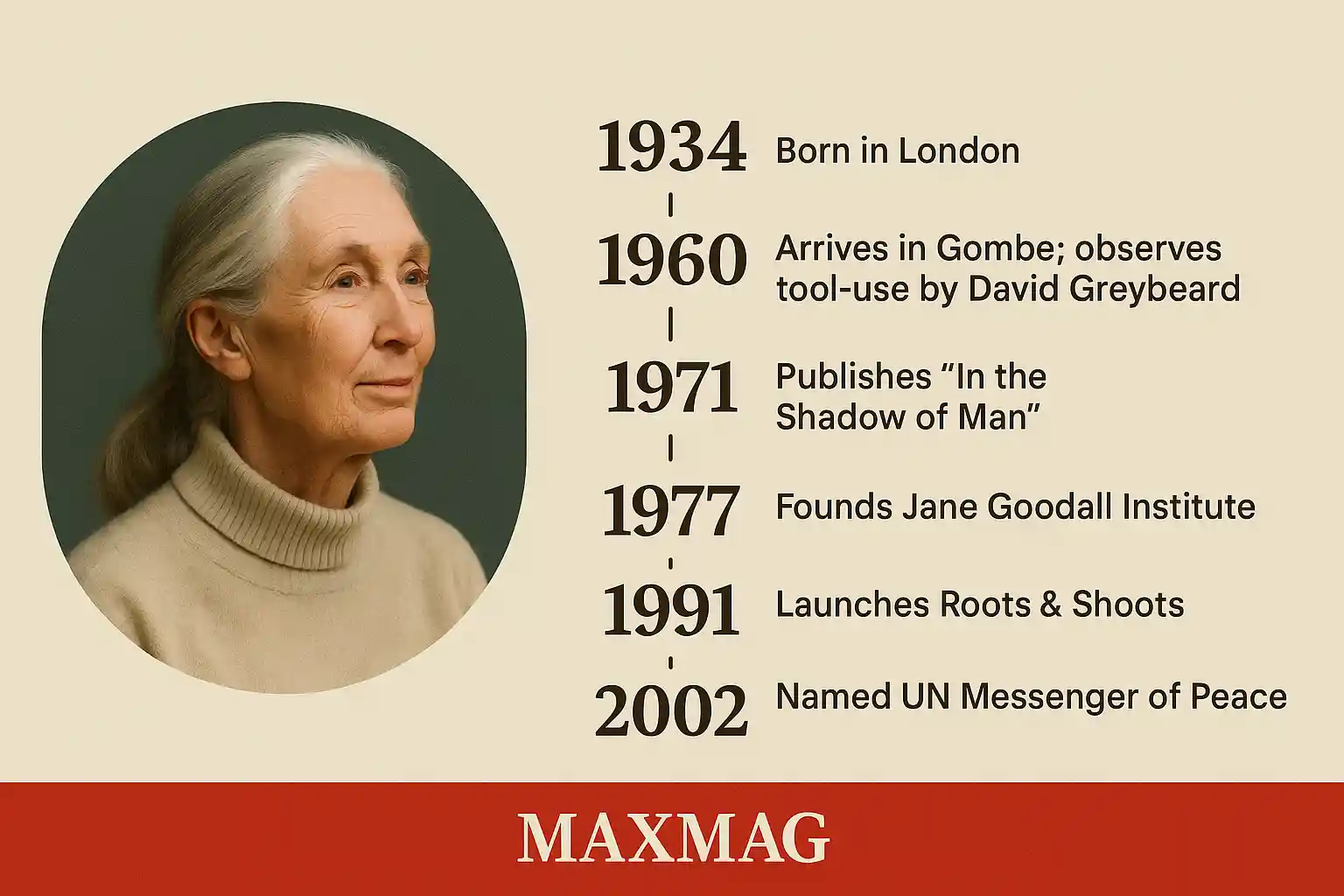

By her early twenties, Goodall arrived in East Africa on a secretary’s salary and a reader’s appetite. Louis Leakey saw in her not a credential but a capacity: attention that didn’t flag and the confidence to admit what she didn’t know. He sent her to the lakeshore forest that would become the central stage of the Jane Goodall biography, a narrow emerald band above the water where paths are made by repetition and chimpanzee families have lineage as intricate as any royal chart.

Reaching Gombe meant boat rides from Kigoma, supplies lashed against the weather, and a willingness to accept that the forest owns the schedule. The camp was spare: canvas, notebooks, binoculars, patience. At first, the apes vanished at the sound of her approach. She waited. Returned. Waited again. Over months, fear thinned to tolerance; tolerance thickened into curiosity; and one individual—David Greybeard—trusted her enough to let the discipline’s old assumptions unravel in the open. In those quiet hours, the Jane Goodall biography shifted from aspiration to evidence.

What followed undermined a brittle hierarchy. Tool-use was not uniquely human. Hunting could be cooperative among apes once thought to be vegetarian saints. Social life was not a haze of instinct but a sequence of choices constrained by rank, kinship, and context. The early pages of the Jane Goodall biography did not polish a myth; they recorded a community.

Inside a Jane Goodall biography: methods that changed the rules

Goodall’s approach was disarmingly simple and, at the time, heretical. She named individuals rather than numbering them, mapped family ties, and wrote behavior in narrative detail with dates, places, and weather. Critics accused her of sentimentality; she answered with data. Names made longitudinal analysis possible. You can’t trace a lineage if your subjects are ciphers. Over years, patterns emerged: mothers tutoring young in foraging techniques; coalitions forming and dissolving; reconciliations after fights that looked, to any honest observer, like peacemaking.

Tool-use came first to a global audience: stripped twigs dipped into termite mounds, then pulled out writhing with food. The telegram from Leakey—“Now we must redefine tool, redefine Man, or accept chimpanzees as human”—has been quoted so often it risks cliché, but it captured the shock. The Jane Goodall biography cracked the story we told about ourselves without diminishing our uniqueness; it merely forced us to share attributes we had hoarded.

Another disruption followed: meat-eating and organized hunts. That observation didn’t flatten differences; it complicated them. Apes could be tender or violent, ingenious or impulsive, depending on history and circumstance. The Jane Goodall biography replaced caricature with range.

It also confronted its own learning curve. Early provisioning—offering food to speed habituation—likely altered some dynamics, a fact Goodall and colleagues didn’t hide. They adjusted protocols, tightened controls, and documented the changes. Science, like forest life, is iterative. The Jane Goodall biography didn’t mistake adaptation for failure; it treated it as integrity.

Field notes that rewrote primatology — a Jane Goodall biography in first discoveries

As her notes moved from camp to journals and then to books and film, two audiences formed: scholars who reshaped research questions around individual life histories, and a public that recognized its reflection in the eyes of another species without collapsing the differences. In both spheres, the Jane Goodall biography functioned as an argument for time—years, not weeks; communities, not samples; stories, not just summaries. Careful coverage mattered. A richly reported Smithsonian Magazine profile of Jane Goodall gave context to discovery without sanding off complexity.

Television crews arrived, photo essays ran, and a generation met David Greybeard, Flo, and Fifi at the breakfast table. Visibility has a double edge. It can elevate the work; it can also simplify it into hagiography. The Jane Goodall biography has always done best when the camera lingers on process: damp notebooks, mosquito nets, long stretches of “nothing” that make the somethings legible. Goodall’s insistence on precision in public—resisting the well-intended myth that chimps are gentle caricatures of ourselves—kept the story honest.

Media also accelerated philanthropy. Projects that require years of salaried patience need someone to foot the bill. When coverage was careful, it raised money without raising false hopes. When it wasn’t, the Jane Goodall biography had to do repair work, reminding donors that conservation is less a moment than a maintenance plan.

Media, myth, and the Jane Goodall biography

In scholarly venues, the ripple effects were immediate. Graduate students redesigned research questions; statistical models evolved to handle longitudinal, relational data. Debates sharpened: How far can we interpret a vocalization? What counts as teaching? Does culture exist in nonhuman animals? The Jane Goodall biography did not shut down these questions; it made them unavoidable.

From science to advocacy: the modern Jane Goodall biography

By the 1990s, Goodall was spending most of her year on the road: schools in the morning, policymakers after lunch, community meetings at night. The Jane Goodall Institute expanded from a research hub into a network linking habitat protection, education, and livelihoods. The Jane Goodall biography transformed from a singular narrative into a chorus: Tanzanian field teams, local rangers, teachers, agronomists, and youth leaders who made the work plural.

Roots & Shoots became the most visible expression of that pluralism. Rather than prescribing projects, it asked students to map what their communities needed and to act on it. A club in Kigoma might plant native trees along a stream; a classroom in Ohio might remove invasive plants from a local park; a team in Shanghai might design a campaign to reduce plastic waste. The Jane Goodall biography modeled agency: change doesn’t trickle down; it grows outward.

The advocacy pushed policy as well. Goodall testified and lobbied against invasive biomedical research on great apes, arguing that intelligence and social complexity carry obligations on our side. Over time, laws and funding patterns shifted in the United States and elsewhere. Sanctuaries grew; some labs shuttered. The Jane Goodall biography made the moral case without treating moral clarity as a substitute for scientific rigor.

Legacy, method, and media: mapping the Jane Goodall biography beyond the forest

What endures when the scientist steps away from the field camp? In Goodall’s case, three legacies stand out. First, a redefinition of method: long-term, individual-based observation as a gold standard in primatology and a model for other taxa. Second, a redefinition of narrative: the return of storytelling to science communication without sacrificing accuracy. Third, a redefinition of conservation: investing in the people who live with wildlife—land-use planning done with, not to, local communities; monitoring that trains residents to gather and interpret data; livelihoods that reduce pressures to clear forests. The Jane Goodall biography shows that conservation is not a luxury good; it is infrastructure for the future.

Technology reinforced these shifts. Satellite imagery tracks deforestation in near-real time; acoustic sensors detect chainsaws and gunshots; environmental DNA reveals who has passed through a stream without being seen. JGI and partners integrated these tools with community-led mapping and long-term behavioral records. The Jane Goodall biography in the 2020s is comfortable with both dashboards and drumbeats, smartphones and story circles. For a visual counterpoint that stays close to the ground, see National Geographic’s coverage of Gombe Stream National Park, which threads discoveries through the people who make them possible.

Tech cannot replace trust. The most elegant map cannot negotiate a land-use deal or ease a rivalry between villages. That takes time, a shared pot of tea, and the unglamorous repetition of follow-through. The Jane Goodall biography keeps returning to a field principle that also works in politics and journalism: witness is a method.

Why the Jane Goodall biography matters now: climate, youth, and local power

Climate variability and habitat fragmentation are not abstractions at Gombe; they show up as empty fruit trees and riverbeds that run dry too soon. The Jane Goodall biography engages these pressures not with despair but with specifics: corridor planning that respects farms and migration routes; fuel-efficient cookstoves paired with tree nurseries; microcredit programs for women that reduce the incentive to clear forest for short-term gains. Conservation succeeds when dignity does.

There is a generational dimension, too. Young people raised on a diet of crisis headlines can become numb or nihilist. The Jane Goodall biography counters with disciplined hope—neither rosy nor naïve. It tells stories that end with agency: the ranger who dismantles a snare line, the student who designs a backyard biodiversity survey, the mayor who sits down with neighboring councils and a large satellite map to draw a corridor that wildlife and people can both live with.

At the narrative level, the Jane Goodall biography also corrects a persistent error in environmental storytelling: the temptation to cast local communities as antagonists. Poaching, logging, and charcoal production have causes—poverty, energy needs, market demand—that can be addressed with alternatives if people are treated as partners rather than problems. The most durable projects treat residents as co-authors.

Scenes from Gombe: what the notebooks still teach

Late in the day, the Kasakela community gathers at a fecund fig, juveniles ricochet, mothers balance infants, a high-ranking male patrols the periphery with more theater than violence. If you remove the date from the field note, the scene could belong to several decades. Continuity matters. It’s how culture shows itself in species that learn. The Jane Goodall biography keeps insisting on this point: other animals have biographies. Individuals aren’t interchangeable; their relationships accumulate into history.

That insight leads to obligation. To protect a community’s culture, you preserve its classrooms, elders, nurseries—meaning the forest itself. Here the romance of fieldwork dissolves into logistics: mapping corridors, negotiating with landowners, training rangers, finding money for clinics and schools. The Jane Goodall biography is a ledger of such tasks, not because they are glamorous but because they work.

In that same ledger live the moments that sustain morale. A snare removed before it injures anyone. A hillside, replanted by students, that throws shade over a schoolyard. A community meeting where a grievance from ten years ago is aired, acknowledged, and eventually set aside so a corridor can be drawn. The Jane Goodall biography treats these as outcomes, not footnotes.

The craft of communicating science

Goodall’s public voice is steady, almost conspiratorial, as if sharing a fact you already suspected was true. She avoids jargon unless it clarifies. She lets scenes do the work before she names the concept. Journalists recognize the craft. The Jane Goodall biography is a lesson in how to cover crisis without stripping readers of agency: pair candor with specificity, then end with work people can do where they live.

That craft extends to the use of outside storytellers. A Smithsonian Magazine profile of Jane Goodall offers historical context without the distortions of hero worship. National Geographic’s Gombe coverage marries photography with field reporting that tracks discoveries and conservation across decades. Both demonstrate how popular media can enlarge, rather than flatten, complex work.

The Jane Goodall biography also models correction as a public act. When early methods required revision, Goodall said so. When a myth about “gentle vegetarian apes” persisted, she countered with evidence. When hope risked sounding like escapism, she defined it as discipline: a way of structuring attention so that solutions are visible.

Measuring impact without flattening meaning

Philanthropy and policy love metrics: hectares restored, snares removed, households using efficient stoves, students enrolled in Roots & Shoots. These matter. They keep programs honest and help choose among trade-offs. But some effects resist counting. A council that now debates land use with ecological data on the table; a former poacher who guides rangers along the path he once walked to set traps; a regional university lab led by a scientist who grew up neighboring the park—these are civic infrastructures as real as a road.

The Jane Goodall biography refuses to choose between numbers and narratives. It understands that a dashboard without stories becomes abstraction, and a story without a dashboard becomes theater. The trick is the same as in the forest: watch long enough to know which details carry weight.

The unfinished work

Threats remain. Demand for bushmeat and the exotic pet trade continues to pull infants from their families; charcoal markets chew through forests; climate extremes scramble fruiting schedules and force hard choices on farmers. The Jane Goodall biography does not romanticize these pressures. It lays out plans that are technically sound and politically possible: cross-border corridor agreements, livelihood programs that make conservation rational, and law enforcement matched to local realities rather than donor expectations.

Succession is another question. Movements cannot depend on a single figure. The institute’s bet is on decentralization: training Tanzanian scientists and rangers, elevating regional leadership, privileging local partners in funding decisions, and letting youth networks build their own projects rather than distributing prepackaged kits. In that sense, the Jane Goodall biography is already plural; it merely needs to keep making room.

There is also the matter of listening differently. As AI models become capable of parsing vocalizations and behavior at scale, we may hear layers of chimpanzee communication that were previously invisible to us. The Jane Goodall biography began with humility—naming, waiting, watching—and its next chapters may require the humility to learn from machines without letting them replace the human relationships that make any of this possible.

What the forest gave back

People often ask Goodall where her steadiness comes from. She answers with a small list: a mother who encouraged curiosity rather than punishing it; a field site that demanded patience; and the thousands of strangers who shook her hand and told her what they were doing in their own towns. The Jane Goodall biography is, in that telling, a collective achievement. It belongs to field assistants with impossible eyesight, to rangers who walk the same ridge lines until they know the stones by feel, to teachers who remind students that attention is a kind of love.

In her late eighties and nineties, Goodall ends many talks with a simple triad: the kind of consumer you will be, the kind of citizen you will be, the kind of ancestor you will be. It is not a slogan; it is a beat reporter’s checklist for a planet story that refuses to end. The forest taught a graduate-school dropout to build a laboratory without walls. The community around that forest taught the world that conservation is not a sermon but a set of habits. And the ongoing Jane Goodall biography asks only this: that we keep looking closely enough to earn the right to act.

Companions, challengers, and the work of continuity

Every long project gathers companions and critics. Photographers such as Hugo van Lawick helped translate field notes into images that could travel; Tanzanian field assistants contributed knowledge that never fit neatly into academic acknowledgments; policy advocates turned observations into legal arguments. The Jane Goodall biography gains dimension when these collaborators step into frame. Movements harden into institutions unless they keep inviting new voices; JGI’s strongest programs today are those where former students now design the next round of research and outreach.

Critique, too, has been part of the engine. Scholars questioned early provisioning, cautioned against over-interpretation of behavior, and pushed for more standardized data collection. Those challenges did not diminish the work; they refined it. In practical terms, this meant revising protocols at Gombe, expanding partnerships with regional universities, and publishing methods with an eye to replication. In narrative terms, it kept the Jane Goodall biography from collapsing into a myth of inevitability: progress came from course corrections as much as from first discoveries.

Continuity now depends on two commitments: local leadership and patient funding. The former ensures programs fit culture and context; the latter makes it possible to watch individuals and families across decades rather than grant cycles. Donors who want quarterly miracles will always be disappointed by forests; donors who invest in ten-year baselines and community land-use plans tend to see results that last. That is the quiet editorial line running through this whole story: a Jane Goodall biography is, at heart, a case for time.