Few inventions have reshaped everyday life as profoundly as frozen food. Today, we take it for granted—reaching into our freezers for vegetables, entrees, or desserts. But this everyday convenience has a dramatic origin story that started with one man’s curiosity in the Canadian Arctic. Clarence Birdseye’s legacy is the starting point of the history of frozen food industry, a tale that combines survival, science, and serendipity.

How Arctic Observation Sparked a Global Industry

In 1912, Clarence Birdseye, a young naturalist working with the U.S. Biological Survey, was sent to the icy wilderness of Labrador, Canada. There, he noticed a remarkable practice among the Inuit people: they would catch fish and expose them to the freezing air, where the fish would become rock-solid in mere minutes.

But what fascinated Birdseye most was not the speed of the freezing process—it was the quality of the food when thawed. Months later, the fish retained its texture, flavor, and freshness. Compared to the mushy, unappetizing frozen foods common in the United States at the time, this was nothing short of a miracle.

Birdseye realized the secret was in the speed of freezing. Quick freezing prevented the formation of large ice crystals, which otherwise damaged food structure. This was the “aha” moment that set the gears of innovation in motion—and ignited the modern history of frozen food industry.

🧪 From Basement Experiments to Industrial Patents

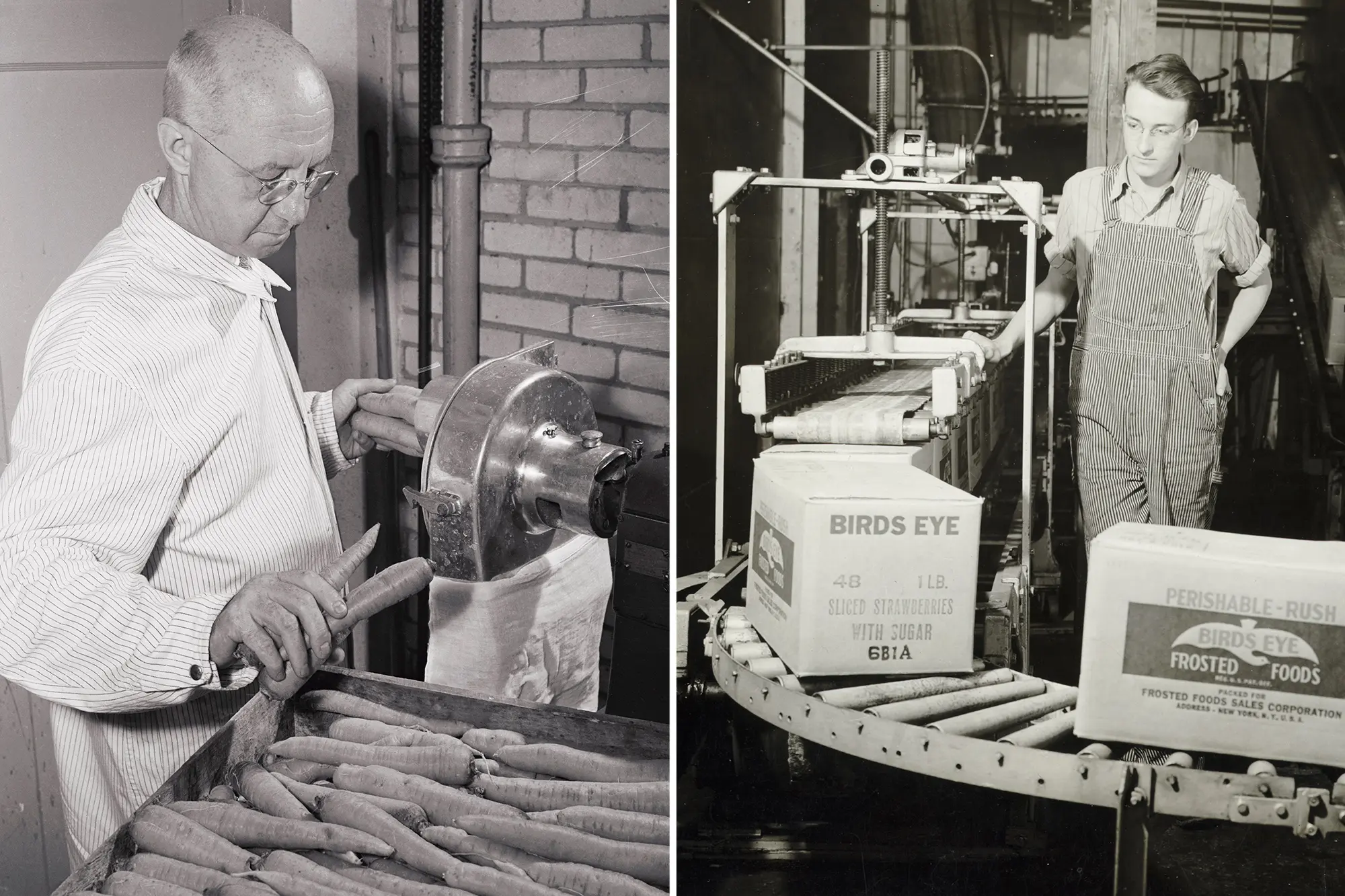

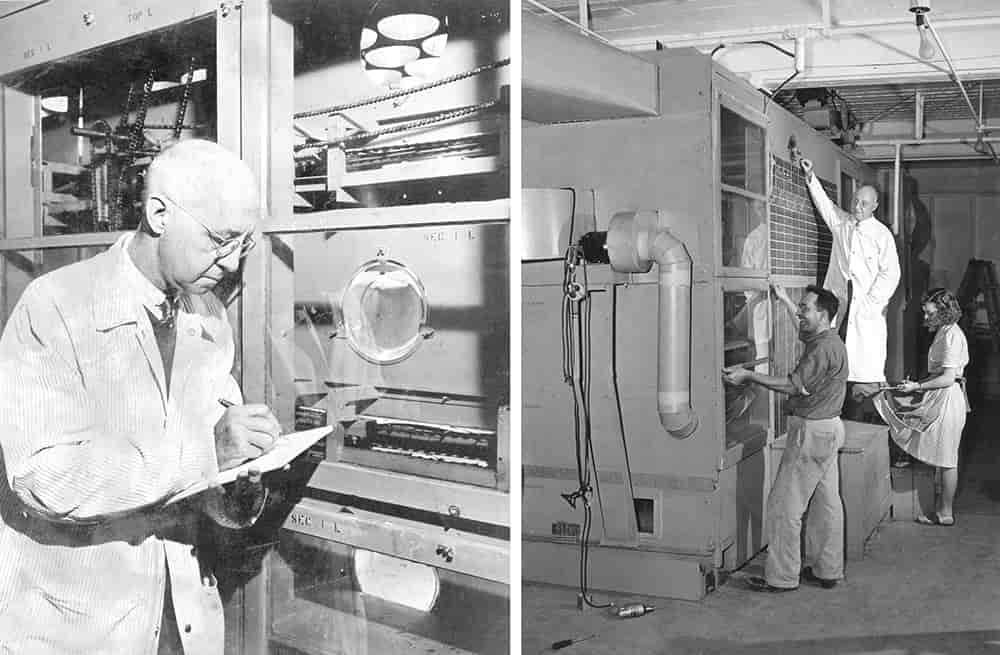

Returning to the U.S., Birdseye began his experiments using a fan, blocks of ice, and insulated boxes. He tested different foods, techniques, and packaging materials. Eventually, he developed a prototype machine that used two chilled metal plates to press and freeze food from both sides simultaneously.

In 1925, Birdseye patented his flash-freezing machine and launched General Seafood Corporation in Gloucester, Massachusetts. His company focused first on frozen fish fillets, but he quickly expanded to include meats, fruits, and vegetables.

By 1929, Birdseye’s success attracted the attention of the Postum Cereal Company (later General Foods), which bought his company and patents for $22 million (over $360 million today, adjusted for inflation). It was a turning point not just for Birdseye, but for the entire trajectory of the history of frozen food industry.

📘 Explore the USDA’s insights on food preservation at NIFA

🧊 The History of Frozen Food Industry and Its Transformation of Daily Life

The 1930s marked a slow but steady rise in the popularity of frozen foods. Initially, adoption was limited due to lack of infrastructure. Most homes didn’t yet own refrigerators with freezers. But Birdseye, ever the forward-thinker, collaborated with grocers and manufacturers to develop freezer display cases, allowing frozen products to be sold in stores.

World War II accelerated the adoption of frozen food. Governments needed preserved meals for troops overseas, and frozen goods met this demand efficiently. Post-war, as the economy boomed and freezers became household staples, frozen foods became synonymous with modern convenience.

By the 1950s, the arrival of TV dinners—individually packaged, complete meals that could be heated and served with minimal effort—symbolized the rise of consumer-centric innovation. They targeted time-strapped homemakers, embraced television culture, and carved out a new market segment.

📰 Read more on postwar food trends at Smithsonian Magazine

🍕 Milestones in the History of Frozen Food Industry

The history of frozen food industry is marked by a series of key milestones:

-

1912–1916: Clarence Birdseye makes his discovery in Labrador.

-

1925: He patents his first commercial flash-freezing machine.

-

1929: General Foods acquires Birdseye’s business and patents.

-

1930s: Frozen vegetables, fruits, and meats reach stores in select cities.

-

1953: Swanson introduces the first frozen TV dinner.

-

1960s–70s: Widespread adoption as freezer ownership becomes common.

-

1980s–2000s: Expansion into ethnic cuisines, premium options, and fast food.

-

2020s: Rise of clean-label, organic, and plant-based frozen offerings.

Each step reflects the industry’s responsiveness to social change—from war to women joining the workforce to health-conscious consumer trends.

🌍 A Cornerstone of Global Food Security

What began as a local curiosity evolved into a global solution. The history of frozen food industry mirrors humanity’s broader challenges: feeding a growing population, preventing waste, and providing nutrition affordably.

Today, frozen foods make up 30% of all food shipped internationally. Entire economies, particularly in cold-storage logistics and food processing, now depend on frozen infrastructure.

Developing nations also benefit. Regions lacking robust agricultural systems or facing frequent droughts can import frozen produce that remains viable for months. It’s not just about convenience—it’s about sustainability and equity in food access.

🌐 Learn more at World Resources Institute

🔬 The Science of Freezing: More Than Just Cold

Freezing food seems simple, but the science is anything but. The rate at which food freezes determines how much moisture is retained and how nutrients are preserved. Birdseye’s technique involved lowering the food’s temperature to -40°F within minutes—ensuring tiny ice crystals that did not rupture cell membranes.

Today, methods have evolved:

-

Cryogenic freezing using liquid nitrogen or CO₂

-

Individual Quick Freezing (IQF) for vegetables and fruits

-

Vacuum packaging for moisture and oxygen control

These innovations allow modern frozen foods to retain up to 90% of their original nutrients. In some cases—like flash-frozen spinach or berries—nutrient content may be higher than fresh produce that has spent days in transport.

🛒 Consumer Trends in the Frozen Food Market

Modern consumers are far more discerning. A few decades ago, frozen food had a reputation for being overly processed and sodium-heavy. Today, that narrative has shifted.

In a recent survey by the Food Marketing Institute, over 70% of consumers reported regularly buying frozen meals with clean ingredients, and 40% seek out frozen organic products. Brands now emphasize:

-

Transparent labeling

-

Global recipes and fusion flavors

-

Low-carb and keto options

-

Plant-based proteins

The frozen aisle is no longer an afterthought—it’s a place of culinary exploration.

🛍 Check out modern food trends at Food Business News

🎥 Culture, Convenience, and the American Freezer

Frozen food has become a cultural artifact. The very idea of “TV dinners” evokes nostalgia for mid-century America, where families gathered around their new television sets with aluminum trays in hand.

Advertising campaigns played heavily on modernity, gender roles, and domestic ease. “Just heat and serve!” became a mantra for a generation learning to balance home and work.

In more recent decades, frozen foods have adapted to microwave ovens, dietary fads, and gourmet trends—proving that they’re as culturally flexible as they are scientifically sound.

🧠 Birdseye’s Legacy: More Than a Brand

Although the name Birds Eye remains a well-known frozen food brand, Clarence Birdseye’s true legacy lies in his approach: merging observation, experimentation, and business savvy.

He didn’t invent freezing—but he industrialized it. He didn’t sell food—he sold a system, a technology, and a way to control nature’s limitations.

Few inventors can claim to have improved the lives of billions of people through something as intimate as daily meals. Yet that’s exactly what Birdseye accomplished.

🔎 Dive deeper with PBS American Experience

🔮 What’s Next in the History of Frozen Food Industry?

Looking forward, frozen food continues to evolve in response to climate, health, and consumer ethics. Some emerging trends include:

-

Zero-waste processing in manufacturing

-

Solar-powered cold chains in developing nations

-

3D-printed frozen foods for specialized nutrition

-

AI inventory management to reduce spoilage and optimize storage

Even now, startups are working on personalized, frozen meal plans using DNA insights or lifestyle data—something unimaginable even a decade ago.

The frozen food industry may have cold products, but its future is red hot.

❓FAQ: About the History of Frozen Food Industry

Q1: Who invented frozen food technology?

A: Clarence Birdseye is widely credited with inventing the flash-freezing technique that launched the frozen food industry in the 1920s.

Q2: How does freezing preserve food?

A: Fast freezing prevents large ice crystals from forming, which helps maintain the texture, nutrients, and flavor of food.

Q3: When did frozen food become popular?

A: After WWII, frozen food became common in American homes, especially with the introduction of household freezers and frozen TV dinners.

Q4: Is frozen food nutritious?

A: Yes. Flash-frozen food retains most nutrients and can be healthier than “fresh” food that’s been sitting in transport or on shelves.

Q5: What’s the future of frozen food?

A: Trends point toward sustainability, plant-based options, and AI-driven production and distribution systems.