In the usual telling of twentieth-century biology, the spotlight falls on the double helix and the race to discover DNA’s structure. Yet behind that iconic image stands another, quieter story: the Frederick Sanger biography of a modest English chemist who worked almost his entire life at the lab bench, and still managed to transform how we read the molecules of life. Twice a Nobel laureate in chemistry, and a central figure in the history of molecular biology, Sanger changed science not with big public gestures but with painstaking, almost stubborn experimental craft.

This Frederick Sanger biography is, at heart, the story of a man who wanted to know “what’s really there” in proteins and DNA, and who was willing to spend years teasing out those answers, amino acid by amino acid, base by base. His work on the structure of insulin and on DNA sequencing did not just win prizes; it opened the way to modern genomics, the Human Genome Project, and the everyday diagnostic tests that quietly shape medicine today. To understand how this happened, we need to follow him from a Quaker childhood in rural England to the fluorescent bands of DNA that lit up a new era of science.

Frederick Sanger at a glance

- Who he was: a British biochemist, twice awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

- Field and era: protein chemistry and nucleic acid sequencing in mid- to late-20th-century science.

- Headline contributions: first full protein sequence (insulin) and the Sanger DNA sequencing method.

- Why he matters today: his techniques underpin the history of DNA sequencing and modern genomics, from rare-disease diagnosis to cancer medicine.

Early Life and Education of Frederick Sanger

From Quaker childhood to future Frederick Sanger biography milestones

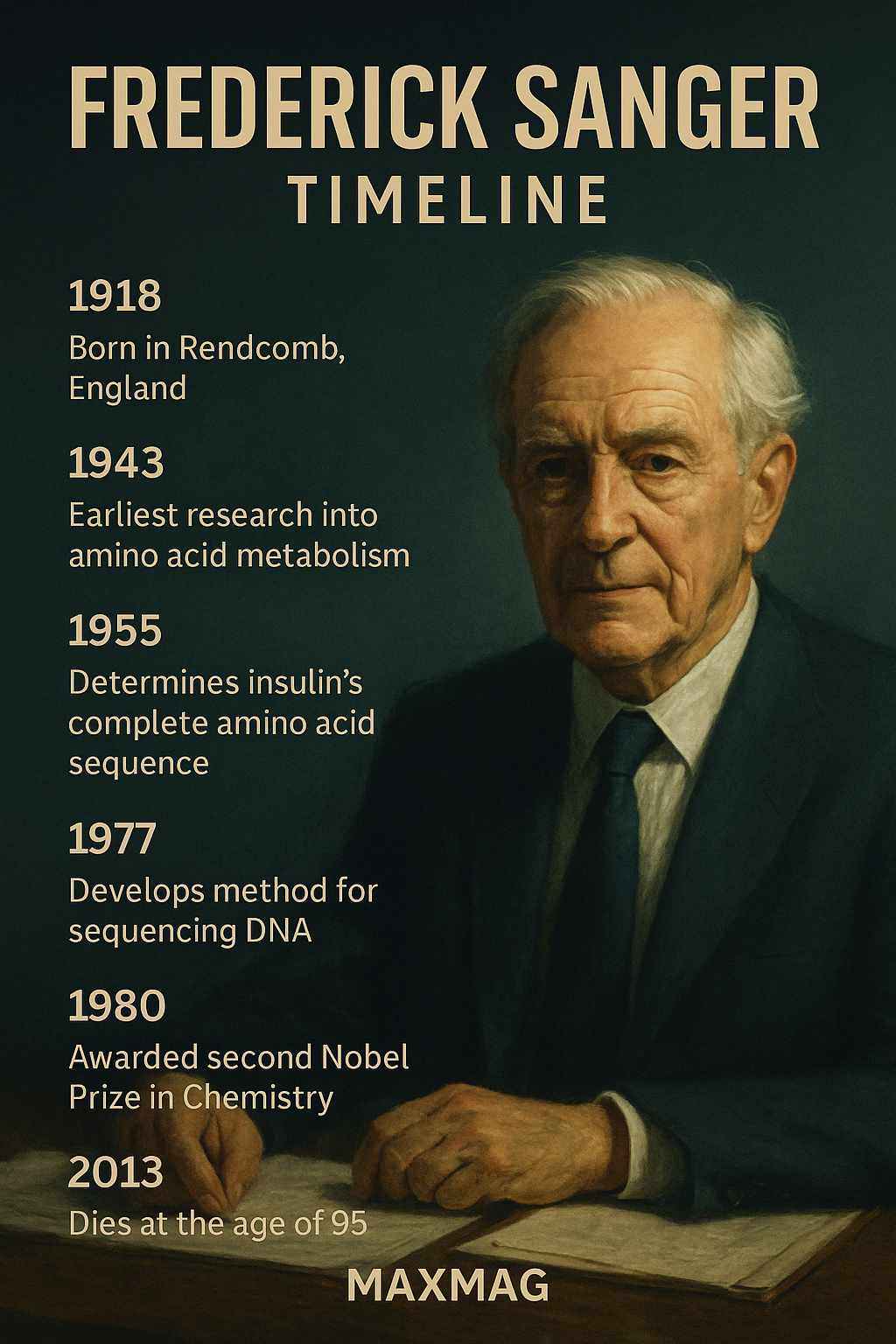

Frederick Sanger was born on 13 August 1918 in the village of Rendcomb in Gloucestershire, England, into a family shaped by medicine and Quaker values. His father was a country doctor, his mother the steady centre of a household that encouraged questioning and service rather than ambition for its own sake. In later interviews, Sanger described a quiet childhood filled with countryside walks and practical tinkering, the kind of environment that nurtured the patient, methodical temperament that would later define this Frederick Sanger biography as a story of slow, cumulative insight rather than sudden flashes of genius.

At school he was not the loudest or most celebrated pupil, but teachers noticed a stubborn independence. He liked to work things out for himself, even if it meant going down blind alleys. That style suited him perfectly when he went on to study natural sciences at St John’s College, Cambridge, where he focused on biochemistry just as the field was evolving into a driving force of modern biology. The Second World War shadowed his student years, but instead of joining weapons research or frontline service, Sanger chose what he saw as constructive work: he trained briefly for relief work and then moved into biochemical research, a path that would eventually make him a pioneer of protein sequencing.

Finding a scientific path: how the Frederick Sanger biography turned to chemistry

For his doctoral work, Sanger joined the biochemistry department at Cambridge, initially studying the metabolism of the amino acid lysine and the nitrogen content of potatoes. It was not glamorous science, and he later joked that his early work was “rather dull”. But those projects taught him how to design careful experiments, handle delicate separations, and be sceptical of simple answers. When he shifted towards protein chemistry and the structure of insulin, he carried that training with him, laying the foundations for the first great chapter of the Frederick Sanger biography in protein sequencing.

There were mentors, but few heroes. Sanger admired older chemists who stayed close to the bench and distrusted those who built empires of students while rarely handling a pipette. That attitude would later define his working style: even as a world-famous scientist, he continued to do his own experiments, a rarity in big-science laboratories. It also kept his focus on practical methods and tools, rather than grand theories – a trait that made him one of the most important experimentalists in the history of molecular biology.

Frederick Sanger biography and the birth of his big ideas

Insulin, proteins and the first great Frederick Sanger biography chapter

In the 1940s, proteins were known to be long chains of amino acids, but no one had yet worked out the precise sequence of a complete protein. Many doubted it could even be done. Sanger chose insulin, a hormone crucial for regulating blood sugar, as his target. It was risky: insulin was chemically tricky, the tools were primitive, and his colleagues warned that he might be wasting his career on an impossible problem. That gamble turned out to be the defining early act of any serious Frederick Sanger biography.

His approach was both simple and inventive. Sanger tagged the ends of insulin’s amino acid chains with a chemical label, broke the protein into pieces, and then carefully worked out the order of the fragments. It was like taking a book, slicing it into paragraphs, and then using special ink to mark every page that begins or ends a chapter. Over eight painstaking years, he built up the sequence of insulin’s 51 amino acids and reconstructed the full molecule. In the process he proved that a protein has a unique, defined structure – a key concept for protein chemistry and for understanding how genes specify proteins.

This triumph earned him his first Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1958 and established him as a protein sequencing pioneer in mid-century molecular biology history. Yet even at the celebrations, colleagues recalled, he seemed slightly embarrassed by the attention. For Sanger, the point was not the medal, but the method – a pattern that recurs throughout the Frederick Sanger biography.

Beyond insulin: from protein structure to nucleic acids

After insulin, Sanger and his group pushed protein chemistry further, extending their sequencing methods to other proteins and refining the underlying theory. But by the late 1950s and early 1960s, a new question was emerging: if proteins had unique sequences, what about the nucleic acids – RNA and DNA – that carry genetic information? The discovery of the DNA double helix had set off intense interest in how genes work, yet there was still no practical way to read the exact order of bases in a gene.

Sanger began by exploring RNA sequencing, trying to adapt his protein strategies to a very different kind of molecule. He and his collaborators developed ways to chop RNA into pieces and then deduce their order, and they identified key molecules such as the formylmethionine tRNA that starts protein synthesis in bacteria. Those successes proved that nucleic acids, too, could be read in full detail, and they prepared Sanger mentally and technically for the leap into DNA sequencing that would dominate the second half of the Frederick Sanger biography.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Frederick Sanger

The Sanger method and the DNA era in the Frederick Sanger biography

The breakthrough that secured Sanger’s place as a genomics pioneer came in the mid-1970s, when he and his team developed a new technique for reading DNA. The “chain-termination” method, now universally known as Sanger sequencing, used modified DNA building blocks that stopped the copying process at specific letters. By running the resulting fragments through a gel and reading off the pattern, scientists could determine the exact order of bases in a DNA molecule.

It was a conceptual masterstroke: instead of wrestling directly with the entire complexity of DNA, Sanger turned the molecule’s own chemistry into a readable code. His group used the method to sequence the first complete DNA genome, that of the bacteriophage φX174, and later human mitochondrial DNA and parts of the bacteriophage λ genome. For the first time, researchers could see entire genes, start to finish, rather than short fragments. The technique quickly spread around the world and became a workhorse of genetic research for decades, dominating the history of DNA sequencing until new “next-generation” methods appeared in the 2000s.

In recognition of this work, Sanger received his second Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980, shared with Walter Gilbert and Paul Berg. That achievement made him one of only a handful of scientists to win two Nobel Prizes in the same category – a fact often highlighted in any Frederick Sanger biography, but one he himself brushed aside with characteristic modesty.

Building institutions: from Cambridge lab to Sanger Centre

Sanger’s contributions were not just technical; they were institutional. At the newly built MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) in Cambridge, he led the protein and nucleic acid sequencing efforts in an environment that prized collaboration and low hierarchy. The LMB became a hub for structural biology and genetics, and Sanger’s methods were embedded in its daily work. Later, as large-scale genome sequencing took off, a dedicated centre near Cambridge was named the Sanger Centre (now the Wellcome Sanger Institute) in his honour. The institute became one of the main engines of the Human Genome Project and a model for modern, high-throughput genomics.

These institutions ensured that the innovations central to the Frederick Sanger biography did not remain the property of a single laboratory. Instead, they shaped how an entire generation of researchers approached DNA, from basic gene discovery to medical genetics and cancer genomics.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Hands-on science and the culture of the lab bench

One of the most striking aspects of the Frederick Sanger biography is how firmly he resisted the drift away from the bench that often comes with scientific seniority. Colleagues remember him in a white lab coat, quietly pouring gels, loading samples, and developing autoradiographs long after he could have delegated those tasks. He believed that important ideas in biochemistry emerged from the details of experiments – the stubborn anomaly in a banding pattern, the unexpected smell from a reaction tube – rather than from meetings or grand theories alone.

His lab culture mirrored that philosophy. Hierarchies were flat, titles downplayed. New students might realise only after months that the shy man at the bench next to them was a double Nobel laureate. Sanger disliked showmanship and discouraged competitive grandstanding; the point was to get the chemistry right. This working style helped to generate a strong sense of shared purpose and made his group a magnet for talented researchers who preferred substance over glamour.

Collaboration, credit and the ethics of discovery

Sanger’s collaborations stretched across chemistry, biology and emerging computational methods. He shared credit generously, often listing his team prominently in talks and papers. When critics argued that methods like Sanger sequencing were “just techniques” rather than breakthroughs in understanding, he quietly pushed back by showing how new tools could reveal entirely new levels of biological organisation. In this sense, the Frederick Sanger biography is also a case study in how method-driven science can reshape theory.

For readers who want a deeper technical overview of how DNA sequencing methods evolved from Sanger’s work to modern platforms, the National Institutes of Health hosts a detailed review of the history of DNA sequencing technologies, which places his chain-termination method in the broader context of genomics. This history of DNA sequencing article traces how a simple concept at the lab bench grew into an industrial-scale enterprise in contemporary biomedicine.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions around the Frederick Sanger biography

“Just a technician”? Debates about method versus theory

Every major scientific life attracts myths, and the Frederick Sanger biography is no exception. One recurring criticism, especially in his early years, was that he was “just” a technician – someone who built tools rather than answering big conceptual questions. In hindsight, that complaint looks misplaced. The ability to read protein and DNA sequences did not merely tidy up details; it made modern molecular biology possible. The debates about whether technique counts as “real science” say more about academic status hierarchies than about the actual impact of Sanger’s work.

Another misconception is that Sanger single-handedly invented everything that bears his name. In reality, his methods emerged from close teamwork. Colleagues like Alan Coulson played crucial roles in developing the plus-and-minus DNA sequencing methods that preceded the classic chain-termination approach. Recognising that collaborative nature does not diminish his standing; it underlines how healthy scientific cultures produce breakthroughs.

Competing methods and the pace of change

Sanger’s DNA sequencing method was not the only game in town. Around the same time, Walter Gilbert and Allan Maxam developed a chemical sequencing technique that also promised rapid results. For a few years, there was genuine competition between the two approaches, and some worried that backing the “wrong” method would delay progress. In the end, Sanger sequencing won out because it was safer, more reliable, and easier to automate, especially as genome projects scaled up.

A final misconception is that Sanger’s work belongs solely to the past, superseded by next-generation sequencing platforms. In practice, Sanger sequencing remains a gold standard for confirming results and for small-scale projects where accuracy matters more than sheer volume. The method still lives on in thousands of diagnostic labs, a quiet, everyday legacy of the Frederick Sanger biography.

Impact on molecular biology and on wider society

From bench chemistry to the Human Genome Project

The most obvious impact of Sanger’s work is on molecular biology itself. By showing that proteins and DNA could be sequenced, he turned genes from abstract entities into tangible strings of letters that could be analysed, compared and engineered. This shift paved the way for the Human Genome Project, which relied heavily on automated Sanger sequencing in its early and middle phases. The history of genomics – from the first bacterial genomes to the draft human genome – is inseparable from the tools that this quiet biochemist developed.

The societal effects are harder to summarise, but they are everywhere. Genetic tests for inherited diseases, forensic DNA fingerprinting, targeted cancer therapies, and much of today’s biotechnology industry all trace their roots back to the chain-termination method. When we speak of a “genomics pioneer” reshaping medicine and agriculture, we are often, whether we say his name or not, referring to the long shadow of the Frederick Sanger biography.

Public recognition and media narratives

Sanger himself never sought celebrity, yet the world noticed his influence. Obituaries and profiles emphasised his double Nobel Prizes, his role in decoding life’s chemistry, and his position in the pantheon of twentieth-century science. One widely read piece in a major US magazine, for example, framed him as a “luminary in molecular biology” whose discoveries helped enable the decoding of the human genome and the development of new drugs. That Time magazine obituary captured how far his influence had spread beyond specialist journals into public conversations about science and progress.

Yet even in such tributes, there is often a tension between the grand language of transformation and the modest man who disliked fuss. Navigating that tension – between the scale of his influence and the smallness of his personal footprint – is one of the themes that gives the Frederick Sanger biography its enduring human interest.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Quaker roots, agnostic outlook

Sanger grew up in a Quaker household that valued honesty, simplicity and service. Those values left a deep mark, even as his own religious beliefs shifted. As an adult he described himself as an agnostic who could not find convincing evidence for God’s existence, but he retained the Quaker emphasis on truth-seeking and integrity. That ethical grounding shaped his approach to scientific disputes and to credit: he was blunt when he thought a claim was unjustified, but he avoided personal attacks.

In interviews, Sanger sometimes suggested that the discipline of experimental science – the need to follow the evidence wherever it leads – had pulled him away from organised religion. Yet he did not see that as a rejection of his upbringing. Instead, he treated both science and Quakerism as attempts to live honestly, even if they answered different questions. That quiet moral seriousness is a thread running through the Frederick Sanger biography, even when the public eye focused more on his prizes than his principles.

Family life and refusal of honours

In 1940 Sanger married Margaret Joan Howe. The couple went on to have three children and built a life in and around Cambridge that combined intense laboratory work with a love of gardening and the outdoors. Friends recall that he spoke of his wife as his most important supporter, providing stability and encouragement during long, frustrating stretches at the bench.

Sanger famously refused a knighthood because he did not want to be called “Sir”, worrying that such titles set people apart. He did, however, accept the Order of Merit, a rare honour in the British system that he seems to have viewed as a recognition of science rather than of social rank. These choices fit neatly with the rest of the Frederick Sanger biography: a man uncomfortable with status for its own sake, more at home with a notebook in the lab or a spade in his garden than at royal ceremonies.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Frederick Sanger

Retirement, reflection and the rise of genomics

Sanger retired from active research in the early 1980s, not long after his second Nobel Prize. By then, the first wave of DNA sequencing projects was underway, and younger scientists were beginning to imagine whole genomes as feasible targets. From his home in the village of Swaffham Bulbeck, he watched these developments with a mixture of satisfaction and distance. He attended some meetings and gave occasional interviews, but he largely left the public arguments about genomics to others.

Retirement did not mean withdrawal from curiosity. Sanger followed advances in molecular biology and remained interested in how his methods were being adapted, from automated capillary machines to early high-throughput platforms. At the same time, he made it clear that he did not want his name to become a brand. The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute exists because colleagues convinced him that attaching his name to a major genome centre would serve science, not his ego.

Death and immediate legacy

Frederick Sanger died on 19 November 2013 in Cambridge, aged 95. Obituaries around the world noted that only a tiny handful of scientists had ever matched his record of two Nobel Prizes in the same discipline. But many of the most heartfelt tributes came from former students and collaborators who remembered not just his scientific achievements but his dry humour, his patience with mistakes, and his insistence that the data, not the hierarchy, should decide the outcome of an argument.

In the years since his death, the Frederick Sanger biography has often been used to illustrate a particular model of scientific life: slow, meticulous, focused on tools and methods rather than grandstanding, yet capable of reshaping entire fields. As genome sequencing has accelerated and spread into clinics, agriculture and forensic science, the gap between the quiet Cambridge labs of Sanger’s time and today’s global sequencing networks has grown, but the conceptual link remains direct.

The Lasting Legacy of the Frederick Sanger biography

Why this life still matters in 21st-century science

Looking back from the vantage point of contemporary genomics, it is easy to treat Sanger’s work as an early chapter in a story whose real action lies elsewhere, in massive sequencing factories and AI-driven analyses. That view misses the point. The tools we now take for granted – the ability to read the genetic code of viruses in an outbreak, to identify cancer mutations in a biopsy, to trace human migrations through ancient DNA – all depend on the conceptual shift that the Frederick Sanger biography represents: the belief that life’s molecules can be read in full, letter by letter, and that such reading is worth the effort.

Sanger’s legacy also challenges some of the clichés about scientific greatness. He was not a charismatic lecturer or a media star. He did not enjoy giving interviews or appearing on television. What he did, instead, was to build reliable methods and institutions, to train others, and to insist that good science is careful science. In an era that often celebrates the loudest voices, the Frederick Sanger biography offers another model: influence through accuracy, patience and generosity.

Finally, his story reminds us that the history of molecular biology is not just a sequence of breakthroughs, but a fabric woven from many kinds of work: the theorist’s idea, the engineer’s instrument, the technician’s skill, the ethicist’s questions. Sanger’s life brought those strands together in a particularly powerful way. Understanding the Frederick Sanger biography does more than honour one scientist; it helps us see how modern science itself evolves – and how the ways we read our own genetic code continue to shape medicine, agriculture and our sense of what it means to be human.

Frequently Asked Questions about Frederick Sanger biography

Below are some common questions readers ask about Frederick Sanger’s life and work, and how this Frederick Sanger biography fits into the broader history of molecular biology and genomics.

Q1: Who was Frederick Sanger and why is he important in molecular biology?

Q2: What is the Sanger sequencing method that features in every Frederick Sanger biography?

Q3: How did Frederick Sanger’s work on insulin influence later discoveries in genetics?

Q4: Why did Frederick Sanger receive two Nobel Prizes in Chemistry?

Q5: Was Frederick Sanger involved directly in the Human Genome Project?

Q6: What aspects of Frederick Sanger’s character stand out beyond his scientific achievements?