If modern biology speaks in the language of circuits, switches, and feedback loops, it is largely because François Jacob taught generations of scientists to think that way. A wartime ambulance officer turned molecular biologist, Jacob helped illuminate how bacteria turn genes on and off—showing that life runs on information and control as much as chemistry. He became one of the most eloquent writer-scientists of the twentieth century, using crisp metaphors to explain what genes do and how evolution tinkers with them. This long-form profile follows the arc of his life and work, situating his discoveries in the larger story of molecular biology, development, and scientific culture. It’s a François Jacob biography that aims to capture both the scientist and the human being behind the lab bench.

Early Life and War Years — François Jacob biography

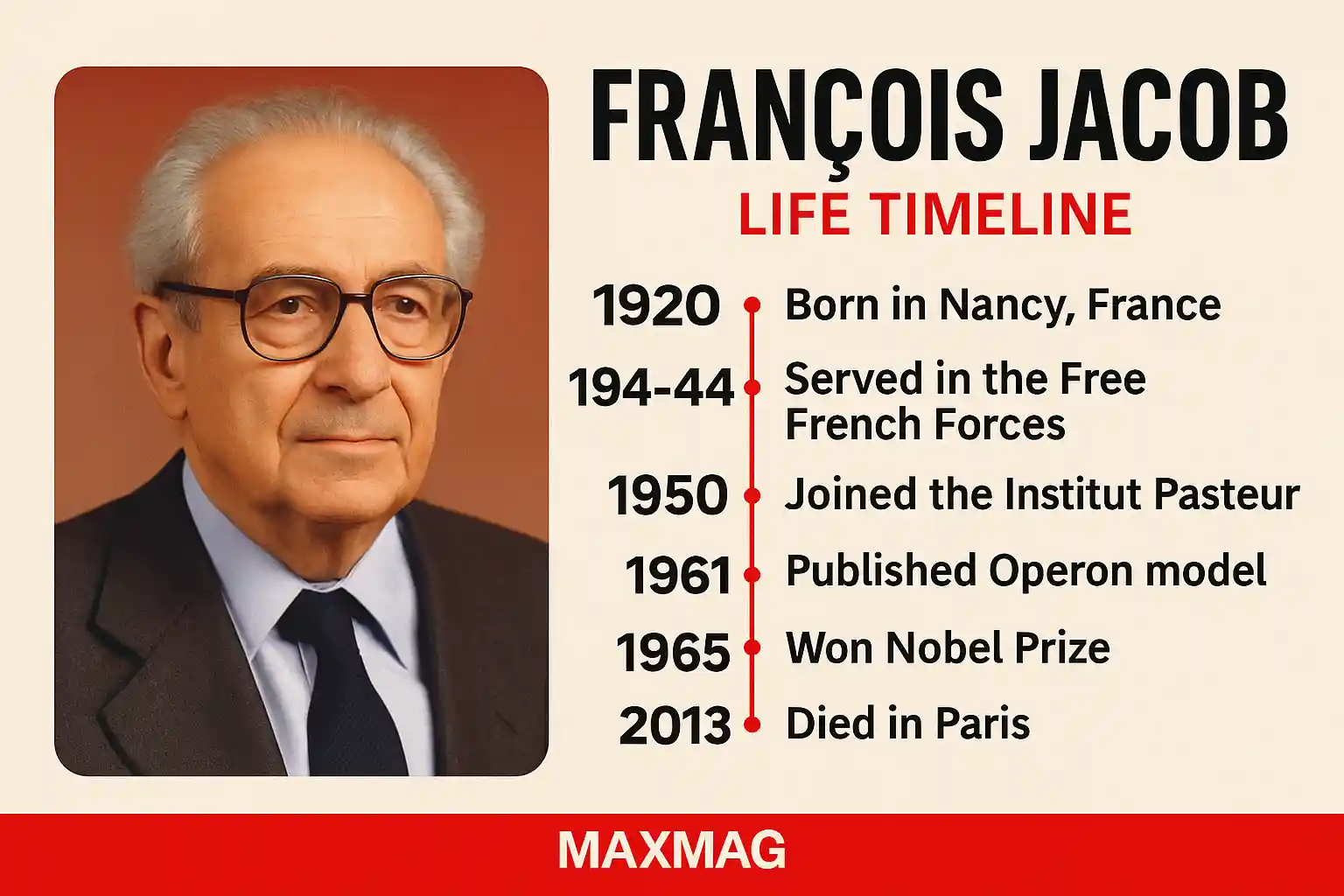

François Jacob was born on June 17, 1920, in Nancy, France, and grew up in Paris. He came of age between two wars, an era that taught him the fragility of institutions and the urgency of action. His early interest was medicine: he entered medical school at the University of Paris with the intention of becoming a surgeon. But history intervened. After the fall of France in 1940, Jacob joined General de Gaulle’s Free French Forces in London and served with distinction in North Africa and later in the Normandy campaign. Severely wounded in 1944, he carried shrapnel and pain for the rest of his life; the injuries also forced him to abandon the operating theater he had imagined as his future. That change of course would set the stage for the François Jacob biography that mattered to science.

Back in postwar Paris, Jacob completed his medical degree but drifted toward research, a shift lubricated by curiosity and the practical limits of his injuries. The clinic’s strict routines gave way to the open questions of biology: How do cells know what to do? How is the torrent of biochemical reactions stabilized into something as coherent as life?

By temperament, Jacob was suited to this kind of inquiry. He was restless but disciplined, skeptical yet imaginative. He loved analogy—an instinct that would eventually help him communicate an entire conceptual revolution. In the lab he developed a reputation for clarity: wherever most people saw a blur, he tried to find the simple diagram underneath. The François Jacob biography that follows is really a story of diagramming the living—without ever simplifying it beyond recognition. The war also changed how he viewed institutions and collaboration. Jacob prized independence but never worked in isolation. He sought out places where difficult, even heretical questions could be asked—and answered with rigor. That sensibility led him to the right mentors, the right colleagues, and the right problems.

From Surgeon-in-Training to Pasteur: François Jacob biography

In 1950, Jacob joined the Institut Pasteur, which had already become a powerhouse for microbiology and virology. Under the guidance of André Lwoff and in close concert with a generation of brilliant peers, he found an intellectual home. At Pasteur, bacteria were not merely organisms; they were tools for understanding fundamental principles. He learned to treat Escherichia coli and its viruses as precision instruments—like stopwatches and voltmeters—for timing reactions and tracing information flow in cells. This was the laboratory context within which the François Jacob biography really takes off.

Early on, Jacob partnered with Élie Wollman to study bacterial conjugation and gene mapping. Using ingenious “interrupted mating” experiments, they showed that genes in bacteria are arranged linearly and can be transferred in a time-dependent fashion from donor to recipient cells. They also helped formalize the concept of the “episome,” a genetic element (like the F factor) that can exist either independently as a plasmid or integrated into the bacterial chromosome. These foundational insights transformed genetics into a dynamic process—one that could be timed, perturbed, and measured.

Such work prepared Jacob exquisitely for the idea that would define his career: regulation. Rather than thinking of genes as perpetually active, he and his collaborators considered them as devices controlled by signals and switches. In short, genes didn’t just exist—they listened. This was also the period when trans-Atlantic conversations became crucial. Jacob interacted with American geneticists including Joshua Lederberg and, soon after, Sydney Brenner and Matthew Meselson. The Pasteur Institute’s internal intensity was balanced by a cosmopolitan network that moved new experiments and ideas quickly across borders. The François Jacob biography gains momentum here: an injured would-be surgeon is now a central node in the birth of molecular biology.

Mentors, Partners, and Lab Culture in the François Jacob biography

No scientist is an island. Jacob’s closest scientific companion in the subsequent years was Jacques Monod, a charismatic biochemist with a gift for theory. Their partnership—sparking, argumentative, deeply productive—became legendary. Alongside André Lwoff, they formed a triangle in which problems could be bounced until their outlines sharpened. Jacob contributed the genetic and conceptual architecture; Monod, the physiological feel for metabolism; Lwoff, the broader biological vision. Beyond this triumvirate stood the Pasteur culture itself: sharp seminar debates, late-night bench sessions, and a high bar for both experimental finesse and conceptual clarity. This collaborative, competitive world is a defining chapter in any François Jacob biography.

The Operon Model and a New Genetics: François Jacob biography

In 1961, Jacob and Monod proposed the operon model to explain gene regulation in bacteria, drawing on years of genetic and biochemical investigations, especially the metabolism of lactose in E. coli. The operon concept is a beautifully economical design: a set of structural genes needed for a given function (say, digesting lactose) is turned on or off by a regulatory gene via a protein repressor that binds to a specific DNA site, the operator. When the inducer appears (lactose or a synthetic analog), the repressor’s grip loosens, RNA polymerase gains access to the promoter, and the operon’s genes are transcribed. A circuit clicks from “off” to “on.” At a stroke, the operon model made gene activity intelligible as control logic. Its power lay not in chemistry alone but in information and timing—a new way of seeing living systems that still anchors textbooks and lectures today. The François Jacob biography is therefore not just a history; it is a manual for thinking.

In parallel, Jacob collaborated with Sydney Brenner and Matthew Meselson on key experiments showing that a short-lived “messenger RNA” carries genetic instructions from DNA to ribosomes. This concept—mRNA as a transient courier—solved a puzzle: how could a stable genome direct rapidly changing protein production? The answer: don’t move the ribosomes to the DNA, move the message to the ribosomes. Once again, Jacob’s work emphasized control through flow and turnover rather than brute stability. The François Jacob biography passes through this watershed: the central dogma acquires a dynamic messenger.

For a concise, authoritative overview of Jacob’s life and contributions, readers can consult an Encyclopaedia Britannica profile. And for those who enjoy history through primary sources, the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s Profiles in Science letters preserve correspondence that shows collaborations forming on paper long before they formed at the bench.

Honors, Books, and Lasting Influence across the François Jacob biography

Recognition followed—culminating in the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine shared with Monod and Lwoff. Yet the prize was only a punctuation mark in a larger story. Jacob became Professor of Cellular Genetics at the Collège de France and continued to shape fields well beyond the operon. He also became one of biology’s most gifted essayists. In La Logique du vivant (The Logic of Life), he mapped how biology turned from descriptions of form to analyses of information, exploring how development and evolution could be understood as layered regulatory programs. In La Statue intérieure (The Statue Within), his memoir, he wrote with luminous restraint about war, injury, and the slow chiseling of a scientific identity. These books are essential to any François Jacob biography because they reveal a thinker who cared about words as much as he cared about data.

From Bacteria to Embryos: Regulation as a Unifying Theme

One of Jacob’s great intellectual moves was to generalize from bacteria to animals: if genes can be regulated in operons, might development itself be a choreography of gene control? Bacteria flip switches to digest lactose; embryos must switch thousands of genes in carefully timed waves to turn a fertilized egg into a body. The difference is magnitude, not kind. That proposition underwrote the rise of developmental genetics and later systems biology. Even though the operon, as such, is a bacterial invention, Jacob’s larger theme—regulation defines identity—crossed phyla.

This line of thought pushed beyond biochemistry into architecture. Genes become modules; modules become networks; networks, guided by signals internal and external, produce form. The idea lent itself to the beautiful diagrams that every biology student remembers: nodes and arrows, promoters and repressors, thresholds and feedback loops. With every new organism studied—Drosophila flies, nematodes, mice—the abstractions became more concrete. You could draw a map and then mutate it to see the image blur, much as Jacob had done with lactose and its repressor.

Jacob also highlighted how regulation helps organisms adapt without rewriting their genomes wholesale. The same genetic code can produce very different outputs depending on context. In other words, biology gets mileage out of control rather than printing new parts. It’s an idea that resonates today in epigenetics, where chemical marks and chromatin states shape gene accessibility; and in synthetic biology, where modular circuits implement designed behaviors.

Lines That Shaped a Field: Quotations from François Jacob

Jacob’s lines live on because they compress entire frameworks into sentences. They are touchstones that teachers and researchers reach for when a long explanation needs a clean edge. Consider these select quotations—each paired with a brief gloss to show why it matters in practice:

- “Evolution is a tinkerer, not an engineer.” — This image from his classic essay on bricolage reframes adaptation as reuse and repurposing. It warns designers not to expect blueprints from nature and encourages scientists to look for patched-together solutions where history constrains form.

- “The dream of every cell is to become two cells.” — A wry reminder that replication is biology’s baseline. When in doubt, ask how a process serves survival and reproduction; much else is downstream of that imperative.

- “What counts is regulation: messages must be sent, received, and modulated.” — A concise credo for gene control. Whether in a bacterium or in a brain cell, timing and context determine meaning.

- “Science advances by simplifying without betraying complexity.” — Jacob’s ethic of explanation. The goal is not to flatten the world but to render it intelligible through good abstractions and merciless controls.

- “In living beings, the past is never past.” — Evolution’s sedimented history shapes today’s possibilities. This line encourages researchers to read constraints as clues to lineage.

- “We are all patchworks.” — From molecules to minds, systems are mosaics assembled over time. The metaphor echoes genomics, where modular domains and networks evolve by recombination and reuse.

Together, these quotable insights form a pocket-sized playbook: think in modules, honor history, test mechanisms by their control logic, and translate complexity into models that can be interrogated. In classrooms, this paragraph often becomes a slide titled “Jacob in Six Lines,” and it functions as a conceptual north star for the entire François Jacob biography presented here.

Jacob and the Messenger: Information as a Substance

The discovery and validation of messenger RNA is a case study in Jacob’s talent for conceptual minimalism. If DNA is the library and proteins the machinery, what carries the plan from stacks to shop floor? By pulse-labeling experiments and density-shift strategies, Jacob and colleagues showed that a short-lived RNA associates with pre-existing ribosomes, decaying as quickly as the protein output shifts. This was not just a piece of the central dogma; it was a temporal key. Control happens by managing lifetimes: stabilize what you must, degrade what you can. This temporality—so obvious, so easy to overlook—became a signature of the Jacob way of thinking, and it remains a touchstone for today’s RNA biology.

The implications of mRNA were immediate and prophetic. Decades later, mRNA would become a therapeutic platform, teaching immune systems to recognize viral proteins. Jacob did not foresee vaccine formulations, but he did insist that control of messages is biology’s master trick. The arc from his benches to today’s biomedical labs is not a straight line, but it is a continuous one.

Philosophy Without Posturing: On Chance, Necessity, and Tinkering

Jacob’s philosophical posture was neither triumphalist nor cynical. He recognized chance and necessity—contingency and constraint—as partners in every biological narrative. His friend and colleague Jacques Monod would title a book Chance and Necessity; Jacob, though aligned, wrote with a different rhythm. He preferred to show rather than announce. Circuits in bacteria were not mechanistic metaphors; they were mechanisms. But they were also arguments about how to generalize: if this kind of logic works here, how might it transpose there?

This is why the operon model is so enduring as a teaching tool. It turns molecular fog into a logic problem that one can carry into new contexts. The tinkerer’s world is not sloppy; it is just constrained by what is available. That insight, now commonplace, was novel when Jacob and Monod articulated it. And it remains a guardrail against naive design thinking in biology.

Institutions, Leadership, and the Classroom

After the Nobel, Jacob did not retire into administration, though he served with distinction at the Collège de France and held advisory roles across Europe. He continued to publish, teach, and mentor. Students recall his insistence on simplicity without simplification, his impatience with sloppy language, and his generosity in crediting others. He was not a showman—the role often fell to Monod—but he was a conductor, coaxing an orchestra of methods and minds into coherence.

He also protected spaces for difficult science. At Pasteur and in the broader French scientific landscape, Jacob argued for resources that could be flexibly applied to new problems. He understood that revolutions are made not only by individuals but by institutions that allow risk. It is a lesson that administrators everywhere cite but too rarely embody.

The Human Story: War, Wounds, and Work

No François Jacob biography should omit the stubborn materiality of his life: the pain in his leg, the shrapnel that surgeries couldn’t fully remove, the fatigue managed in long stints at the bench. War imprinted itself on his posture, his schedule, and perhaps his stoicism. Yet colleagues remember humor and an almost childlike delight in a sharp experiment. He often seemed most alive when discussing controls—how to rule out the obvious, how to corner the real causal agent. The discipline of the field hospital, where one triages and acts, carried over to the lab.

His personal life included tragedy and renewal: the loss of friends in war; the joys and complexities of family; the satisfactions of writing prose that could stand outside the lab. He moved easily between worlds: the molecular and the literary, the formal seminar and the public lecture.

Influence: From Operons to Omics

Today’s “omics” sciences—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics—often feel remote from Petri dishes and lactose broths. But the logic they apply is Jacob’s: identify modules, measure flows, map control points, perturb the system, model the result. High-throughput technologies expand the scale; they don’t abolish the principles. Synthetic biology, too, owes Jacob a debt. When teams design gene circuits that toggle, oscillate, or sense, they are building in the house that operons built. Control is the grammar; constructs are the sentences.

Teaching, likewise, continues in his style. Many instructors begin molecular biology with the lac operon because it is the clearest on-ramp: a demand-driven system that spares energy by default and spends it only when needed. Students who grasp that logic are better prepared to tackle eukaryotic regulation, where enhancers and chromatin add complexity but not different first principles.

Case Study: The Lac Operon as a Teaching Machine

Consider a first-year lab where students measure β-galactosidase activity after adding lactose analogs. Within a few hours, they can plot enzyme production over time, watch repression lift, and see induction as a curve rather than a concept. That humble assay is a distillation of Jacob’s pedagogy: an experiment that doubles as an argument. It shows that regulation, not mere presence of genes, is what makes metabolism responsive. In the language of this François Jacob biography, the lac operon is more than a classic—it’s a machine for teaching what counts as explanation in biology.

From Bench to Book: Writing as Experiment

Jacob’s prose is not ornament; it is method. When he calls evolution a tinkerer, he is performing the same operation he demanded at the bench: stripping a problem to its controlling variables. Good metaphors, for him, were models with nouns. They survived because they helped readers run mental experiments, swapping parts in and out to test how a system might behave. The result is a rare double legacy—papers that changed how labs worked and books that changed how labs thought. This dual craft is vital to any François Jacob biography that wishes to show how a scientist can shape a field twice: first by discovery, then by discourse.

Why Jacob’s Thinking Matters Now

As biologists stitch together cell-wide networks and clinicians interpret torrents of genomic data, Jacob’s discipline of control-first explanation is more relevant than ever. In cancer biology, for example, the same mutated gene can produce radically different outcomes depending on regulatory context; therapies work when they target the wiring, not just the parts list. In synthetic biology, stability and safety come from failsafes and feedback, not from brute force. The thread that binds these practices is exactly what this François Jacob biography has been tracing: a worldview in which information, timing, and history do the heavy lifting.

A Legacy of Clarity

What remains, finally, is a style: define the problem, strip it to essentials, imagine the control logic, test mercilessly, explain cleanly. Although Jacob is anchored in bacterial genetics, his intellectual temperament travels. Developers write code with similar instincts; policy analysts frame trade-offs with the same economy; physicians balance interventions and side effects as circuits of care. That his metaphors left the lab is evidence of their power.

The François Jacob biography ends where it began—with a wounded young man who had to change plans. In that forced change lay a reimagining of genes that made biology more intelligible and more humane. He did not give us a master equation. He gave us a way to think.