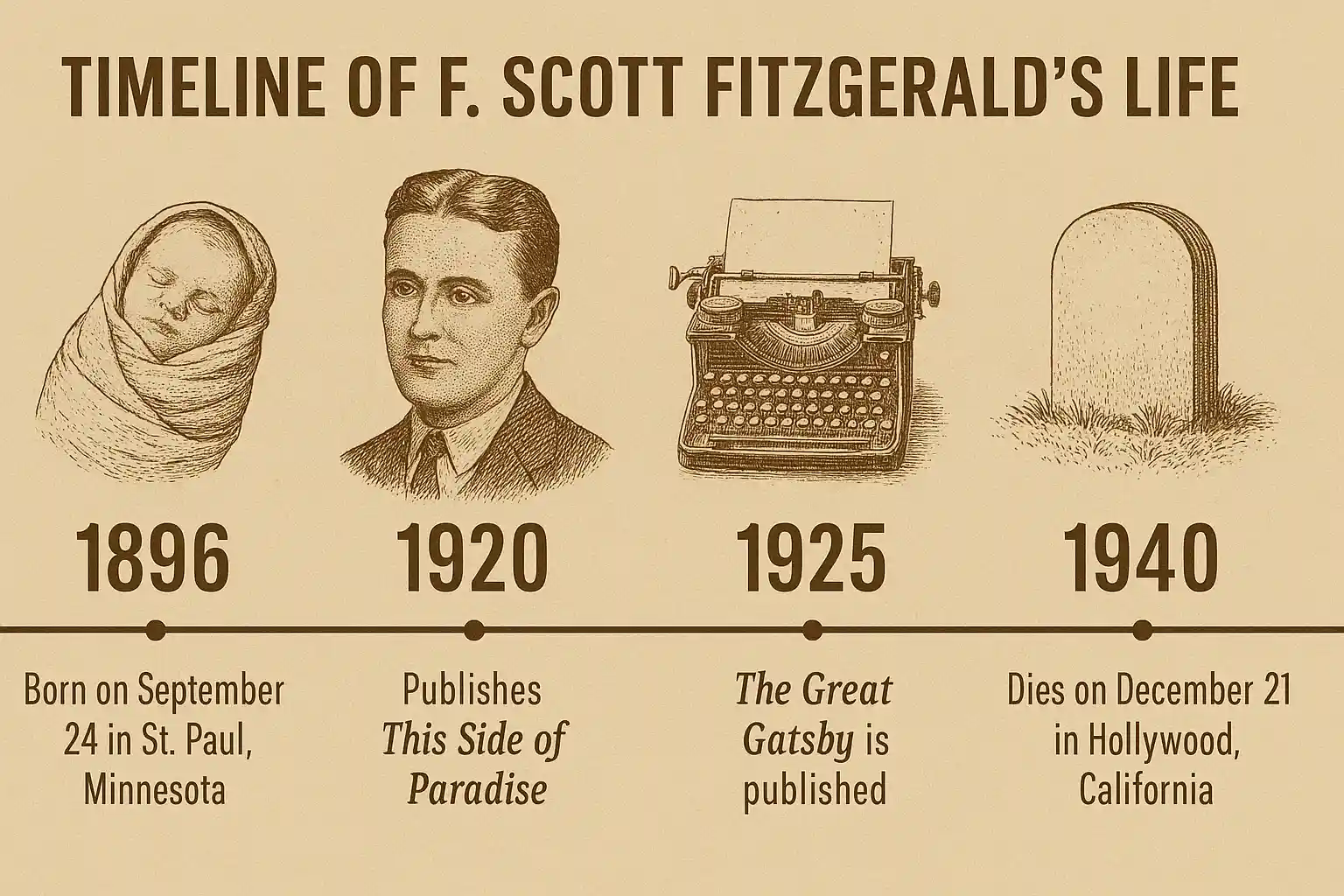

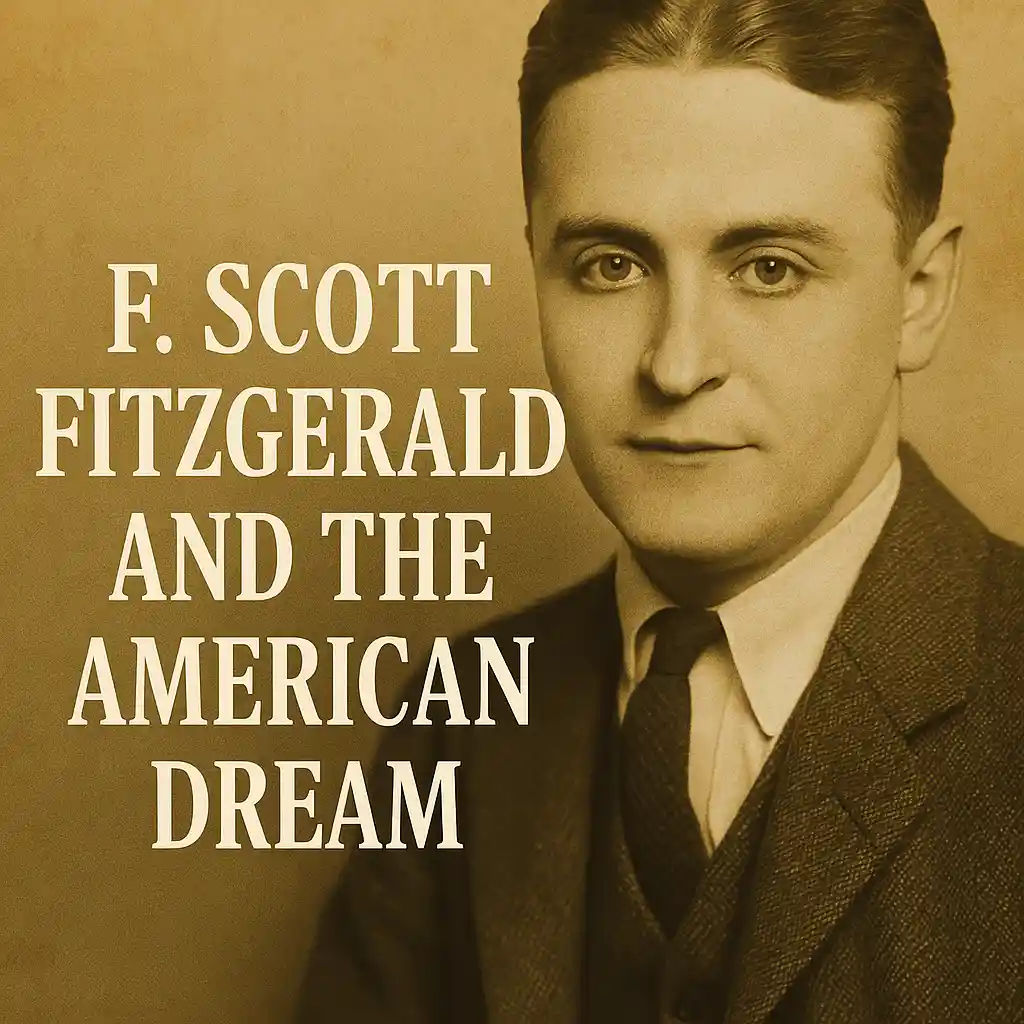

Few twentieth-century writers fused glitter and doubt with the clarity of F. Scott Fitzgerald. His pages shimmer with orchestras and roadsters, but they also listen for the quiet thud of consequences: debts that come due, vows that sour, illusions that lose their tint in daylight. Read today, his work feels less like a museum piece than a living mirror of aspiration—how it begins, how it parades, how it exacts a price. That tension is the heart of F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream, and it remains the reason students, critics, and casual readers keep returning to the green light, the long party, and the longer morning after.

F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream: Origins, Class, and Self-Invention

A good way to enter this theme is to start before the dream takes shape. The young Midwestern boy who devours plays and poems stands at the edge of a nation that promises mobility. His family’s fortunes rise and fall; he absorbs the lesson that status is delicate and that the right accent, the right suit, the right friends can open doors that otherwise stay sealed. Those early fluctuations wire him for a lifelong obsession with class—how it looks, how it sounds, how it polices itself. When he later invents characters who rehearse their manners in front of the mirror, he is not writing from theory but from muscle memory.

The American Dream, as it circulates in the 1910s and 1920s, isn’t a formal doctrine; it is a folk belief. If you study F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream from this angle, you notice how often self-invention is staged as theater. People audition for each other. They rent elegance before they own it. They memorize small talk as if it were scripture. Fitzgerald is alert to the thrill of this performance—the first time a borrowed tuxedo fits, the first night you speak the room’s language without tripping. He is equally alert to the fatigue that follows: keeping up the costume, tracking the bill, worrying that the old past will leak under the new paint.

Even his love stories are arguments with class. The friends, the clubs, the coastal summers—these are not scenery but customs checkpoints. In his hands, romance becomes a passport office where a name is inspected, a background weighed, a future bargained for. That is why F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream never reads like an uncomplicated invitation to rise; it reads like a ledger, a theater program, and a confession—all at once.

F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream in the Jazz Age

It is tempting to treat the Jazz Age as a costume party, but F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream turns it into an x-ray. The parties are real—sequins, orchestras, terraces that talk back to the ocean—but the book’s gaze keeps looking under the tablecloth. The self that the dream invites you to invent is not weightless; it drags a history behind it. That is why the glamour so often sits beside a disquiet you can’t name at first. The characters sense that access and acceptance are different species. They can buy a ticket to the show; belonging is harder.

In the 1920s city, Fitzgerald’s people become vivid studies in performed identity. One character tries on elegance like a new coat; another uses irony as armor; a third polishes a smile that can pass as pedigree. When you read F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream this way, you see the constant negotiation between display and doubt. You also see how the city itself collaborates with the performance. Streets become runways. Bridges become stages. Even billboards speak in the second person, telling drivers who to be.

The Jazz Age also supplies a fresh grammar for risk. Credit expands, bubbles inflate, and the sense that the future will pay for the present becomes a kind of national prayer. Fitzgerald understands the thrill of that posture and the drift of its aftermath. He knows that a society that trades tomorrow for tonight wakes up with an ache that is not only in the head.

Teaching F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream

In classrooms, instructors often organize units around place (Long Island, city, shore), color (gold, green, gray), and voice (who narrates, who is narrated). They ask students to notice how performance becomes policy—how the way a character speaks determines what rooms open, how the staging of a dinner decides what futures feel plausible. The most effective lesson plans treat F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream as a question rather than a verdict. Is reinvention a kind of courage or a kind of forgetting? Can love survive when both people want to be seen differently than they are?

For a concise, reliable overview of the author’s life and works, readers can consult Encyclopaedia Britannica’s biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald. For curated classroom ideas and primary-source context, see the National Endowment for the Humanities’ EDSITEment lesson plan on The Great Gatsby.

Style and Method: The Lyric Reporter

Fitzgerald’s famous sentences dazzle, but the shine is structural, not ornamental. He uses simile the way an architect uses glass: to let you see both the party and the reflection of the party at the same time. Objects do moral work in his fiction. Light isn’t just light—it’s appetite; color isn’t just color—it’s class code. He favors narrators who hover between enchantment and judgment, so the reader shares a double vision: the music and the exit sign, the kiss and the lie, the promise and the price. That is part of the method that makes his social worlds feel so breathable. You hear drawers open, ice clink, tires hiss; you also hear the private arithmetic of desire.

He is also a strategist of structure. A typical Fitzgerald chapter sets a bright scene, plants a quiet doubt, then lets the doubt collect weight until it tips the scene on its side. The famous parties work like time bombs. You watch the choreography—the doors, the laughter, the arrivals—and only later realize that someone has misread the script. For readers exploring this theme, this craft matters: the book’s meanings live not just in what he says but in how the story’s architecture allows glamour and disillusion to occupy the same room.

Zelda, Partners and Paradoxes

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald is often reduced to a shimmering silhouette beside a famous husband. That is a mistake. She was a dancer, painter, and writer whose tastes, rhythms, and daring helped calibrate his tone. Their marriage was both laboratory and stress test: collaboration that blazed, rivalry that singed, devotion that had to survive public scrutiny and private illness. If you want a full account of F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream, you need Zelda at the center of the frame—because desire, performance, and the chaos of ambition were not simply subjects for them; they were the air they breathed. The same currents that animate his fiction—reinvention, risk, the chase for a life larger than one’s coordinates—ran through their days.

Scenes of the 1920s: Money, Music, Velocity

The cultural engine of the 1920s runs on speed. Cars flatten distance, phones compress time, jazz resets posture. Fitzgerald hears the tempo shift and writes it down. He populates rooms with quick talkers, orchestrates entrances like dramatic beats, and choreographs motion so you can feel America learning to walk faster. The visual grammar of the decade—chandeliers, champagne, chrome—proved irresistible to him, but he keeps one hand on the dimmer switch. When the light drops, the furniture looks different. A borrowed life, viewed at 2 a.m., loses its flattering angles.

He is precise about money’s moods. It jokes, it sulks, it brags; sometimes it apologizes. He shows how money can function as anesthesia and as amplifier, numbing some pains while magnifying others. The crispest summary might be this: in his world, cash is both prop and protagonist. It changes conversations simply by being present, and when it leaves, the room learns what things actually cost.

Short Stories: Laboratories of a Theme

His short fiction is a series of laboratories where he tests the dream from different angles. In one story, a character tries to jump class by learning how to speak a new weather. In another, a returned reveler inventories what the party used up in him. In a third, he records the way wealth can feel like an accent that never quite fits your mouth. Across these experiments, the same questions recur: What is the difference between pose and person? How long can desire masquerade as destiny? Could you love someone and still want them to change into a more convenient shape?

Because the stories compress time, they show the cost of aspiration at high resolution. A single sentence can move you from a violin to a hospital corridor. The effect is bracing. You can watch the dream speed through its phases—spark, display, strain, fallout—in a dozen pages. That economy is one reason the short fiction remains an especially useful lens on this theme.

Race, Gender, Class: The Hidden Framework

Fitzgerald wrote inside a culture stratified by money, policed by etiquette, haunted by anxieties about immigration and “new money,” and structured by gender roles that gave women ornamental power and limited agency. He registers these forces with a mix of critique and complicity. The social rooms he draws are exact about how men talk over women, how clubs exclude without announcing their rules, how a joke can serve as a lock. A contemporary reading sees this not as an incidental backdrop but as the very architecture that shapes who gets to dream, how far, and at what cost.

If the American Dream is a promise, the small print lives here. The promise is not evenly distributed. In that sense, F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream becomes a study in access: who can buy a costume that fits, who is asked for papers that don’t exist, who pays for a crash they did not cause. The book’s abiding power is that it lets you admire the shimmer while hearing, faintly but unmistakably, the hum of the machine that makes the shimmer possible.

Film, Music, and F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream Onscreen

Filmmakers love the material because the images arrive pre-lit: a shoreline with a flickering signal, a road where speed is a moral, a city that teaches you to pronounce your new self. Directors keep rediscovering that F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream offers a paradox audiences crave: an invitation to admire the party while suspecting that the party is a test. Some adaptations dial up the glitter; others polish the x-ray. Either way, the story’s circuitry remains visible: longing, performance, collision, accounting.

Music critics have found similar patterns in jazz and pop: crescendos that refuse resolution, hooks that sell you a mood while concealing the bill. The best reinterpretations understand that the point is not to replicate the 1920s but to echo the logic of the dream—how people learn to speak aspiration through whatever sound the era provides. That is why the tale remains elastic across decades.

Work for Hire, Work for Keeps

Magazines paid the rent; novels paid immortality. Fitzgerald said yes to the former because he needed time for the latter. That is not a sad compromise but a craft reality, and it deepens the portrait. The checks bought hours; the hours bought chapters; the chapters taught him how to build a book with the tensile grace he wanted. If you’re mapping F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream, this economic subplot matters: the man who wrote about money also wrote because of money, which is part of why the representations feel lived-in rather than theoretical.

Even in the slicker stories, you sense the novelist working out structures that will matter later. A party becomes a miniature of a nation; a joke becomes a corridor to a wound. The scaffolding is visible if you know where to look.

Hollywood, Typewriters, and a Late Style

The move to the studios gave him fresh machinery to study: deals as dialogue, budgets as destiny. He was fascinated by a world that manufactures dreams for a living, then spends the morning revising them. The tone changes in these years—less champagne, more coffee—but the preoccupations don’t. Reinvention persists; performance professionalizes; power shows its loneliness. A narrative voice once confident enough to glide now stops to measure, to test, to admit uncertainty. That late style adds a final accent, reminding us that even a mythographer of youth can compose with earned sobriety.

A Reader’s Path: How to Approach the Books Now

Start with the famous one, then circle outward. Read the slender novel that everyone knows, and read it twice, a week apart. The first pass is for the surface—plot, spectacle, charm. The second pass is for the wiring—who speaks when, what the rooms do, why the weather turns at the precise moment it does. After that, take three stories that echo the novel’s concerns in different keys. Then make time for the Riviera book, which blooms slowly and asks for patience. Finally, open the Hollywood fragment to watch a great technician reconfigure his tools for a new studio, a new pressure, a new wind.

Along the way, keep a notebook of objects and verbs. Track who pours and who is poured for; track who calls and who is summoned. You will find that the moral of this theme often hides in logistics.

Myth, Marketing, and the Afterlife of a Phrase

The phrase itself—part author’s name, part national promise—has become a kind of brand. It appears on syllabi, in essays, on lecture posters, in think pieces that bring a Roaring Twenties metaphor to the newest boom cycle. There is a risk in that familiarity: the words can turn to air. The antidote is rereading. When you return to the sentences, the moral stakes snap back into focus. The dream isn’t a refrigerator magnet; it’s a thorned vine. Handle with care.

At the same time, the brand’s persistence testifies to the clarity of the match. To talk about aspiration in the United States is to talk, sooner or later, about performance, access, and aftermath. The work articulates those things with a beauty that can look like permission until it sharpens into critique. That slippage—seduction into diagnosis—is the special effect that keeps the books contemporary.

What the Dream Costs: A Moral Inventory

Behind every borrowed elegance is an account. Fitzgerald is specific about currencies: time, reputation, tenderness, sleep. Characters exchange them without naming them, but the trade rates are visible if you watch carefully. A witty dinner may cost two weeks of self-respect; an afternoon’s pose may cost a year of forgiveness with a friend; a lie told in the correct accent may cost the courage to speak in your own voice tomorrow. Put differently, F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream teaches that upward motion can quietly sell off the pieces of yourself you meant to use for living.

The lesson is not abstinence from aspiration; it’s literacy. Know what you’re trading. Decide whether the new costume wants to own you. Ask whether the door you’re opening leads somewhere you would want to sleep. These are adult questions, and the books pose them without sermonizing.

Practical Reading: A Small Toolkit

- Track space. Where scenes happen matters. Waterfront versus valley; terrace versus hallway. Status arranges itself physically.

- Track verbs. Who invites, who commands, who apologizes. Power speaks in grammar before it names itself.

- Track weather. Heat and wind function as moral cues; they change what characters are capable of saying.

- Track money’s manners. Not the sums—the posture. Richness is often a rhythm.

- Track silence. What is not said is part of the argument.

Beyond the Canon: Echoes and Counterpoints

Later writers have complicated and contested the dream that Fitzgerald immortalized. Some narrate the climb from voices and neighborhoods excluded from the earlier rooms; others map the costs to families, to health, to a sense of home. The conversation is larger now and better for it. But the early portrait still matters—not as the final word, but as one of the clearest early x-rays of the myth’s skeleton.

A generous way to use the classic is as a foil. Put a contemporary novel beside it and ask: whose dream is being told here? What kind of gatekeepers appear? What happens to those who don’t want the costume at all? The book makes a lively partner for such pairings because it is itself divided—a text that believes in beauty and suspects what beauty does.

F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream: Legacy and Relevance

A century on, F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream still names a tension people feel in their daily choreography: the desire to appear, to be seen, to be chosen—and the suspicion that visibility might be eating something you meant to keep private. In an era of profile curation and follower economies, the novel’s green light looks less like a bay signal and more like a notification badge. The metaphor migrates without effort because the psychology hasn’t changed. We still trade tomorrow for tonight; we still confuse being watched with being loved.

Universities teach the books because they create an honest classroom for contradictions. You can admire the craftsmanship and argue with the ethics. You can note the sexism and savor the syntax. You can diagnose the class blindness and still feel the ache that animates the story. One reason this theme continues to attract new readers is that the text refuses to solve itself. It leaves you in a disciplined uncertainty, an adult space where hope and harm share a table.

The legacy extends beyond literature. Designers borrow the palette, musicians the cadence, filmmakers the frames. Yet the most important inheritance is ethical. These works train the reader’s appetite not to trust its first hunger. They encourage a question that modern life tries to drown out: “What will this cost, and who will pay it?” That question is the spiritual engine of F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream, and it is why the phrase earns repeating instead of resting as a slogan.

Contemporary Uses: Why We Still Quote Him

When columnists search for a parable of excess, they reach for the Long Island summer. When advertisers want a flavor of gilded longing, they borrow the chandeliers. When critics want to describe a tech boom’s theatrical optimism, they invoke the parties by the sea. The adaptability can be abused—everything becomes “Gatsby”—but its frequency says something true: we don’t have a better shorthand for the beauty and hazard of American aspiration.

Writers admire the control. Even scenes built from silk and chrome have bones. Plot turns are disguised as dances; moral arguments are smuggled inside a dress code. Reread one of the famous chapters and notice how the camera moves. It is a novelist’s camera, not a tourist’s. It lands where consequence will later bloom.

Closing Perspective: Desire, Discipline, Aftermath

Desire is not the villain in Fitzgerald. Cowardice is. The cowardice to tell the truth when the costume no longer fits; the cowardice to admit that the party is asking you to become someone you would not hire to live your life tomorrow. The discipline his narrators learn—slowly, painfully—is not to refuse enchantment but to keep a ledger open while the music plays. As long as we live inside systems that reward display and punish hesitation, F. Scott Fitzgerald and the American Dream will feel like news.