In the late nineteenth century, few figures embodied both the brilliance and the blind spots of modern science as vividly as Ernst Haeckel. Any serious Ernst Haeckel biography has to juggle dazzling marine illustrations, passionate defences of Darwin, bold philosophical claims about the nature of life and mind, and a tangle of controversies that still shadow his name. He was a German biologist, philosopher and artist who helped popularise evolution for a broad public – but he also pushed ideas that today make many readers uneasy.

To read an Ernst Haeckel biography is to move through some of the most dramatic debates in nineteenth-century biology: the struggle to absorb Darwin’s theory of natural selection, the attempt to build a “tree of life” for all organisms, and bitter arguments over embryos, race and religion. He drew thousands of species with hypnotic precision, coined terms such as “ecology” and “stem cell”, and founded a museum devoted to evolution. Yet his theory that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” – the idea that embryos replay evolutionary history – became one of the field’s most criticised slogans. Understanding this complicated scientist helps us understand how modern biology grew out of both rigorous observation and powerful, sometimes dangerous, metaphors.

Ernst Haeckel at a glance

- Who: Ernst Haeckel, German biologist, naturalist, philosopher and scientific illustrator.

- Era: Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century science, at the height of the Darwinian revolution.

- Field: Zoology, embryology, evolutionary biology and the history of biology.

- Headline contributions: Champion of Darwinism in continental Europe, author of influential evolutionary works, creator of the iconic Kunstformen der Natur plates and pioneer of ecology as a discipline.

- Why he matters today: The Ernst Haeckel biography illuminates how scientific ideas spread, how images shape public understanding, and how evolutionary thinking can be used – and misused – in wider society.

Early Life and Education of Ernst Haeckel

Childhood in Potsdam and a taste for nature

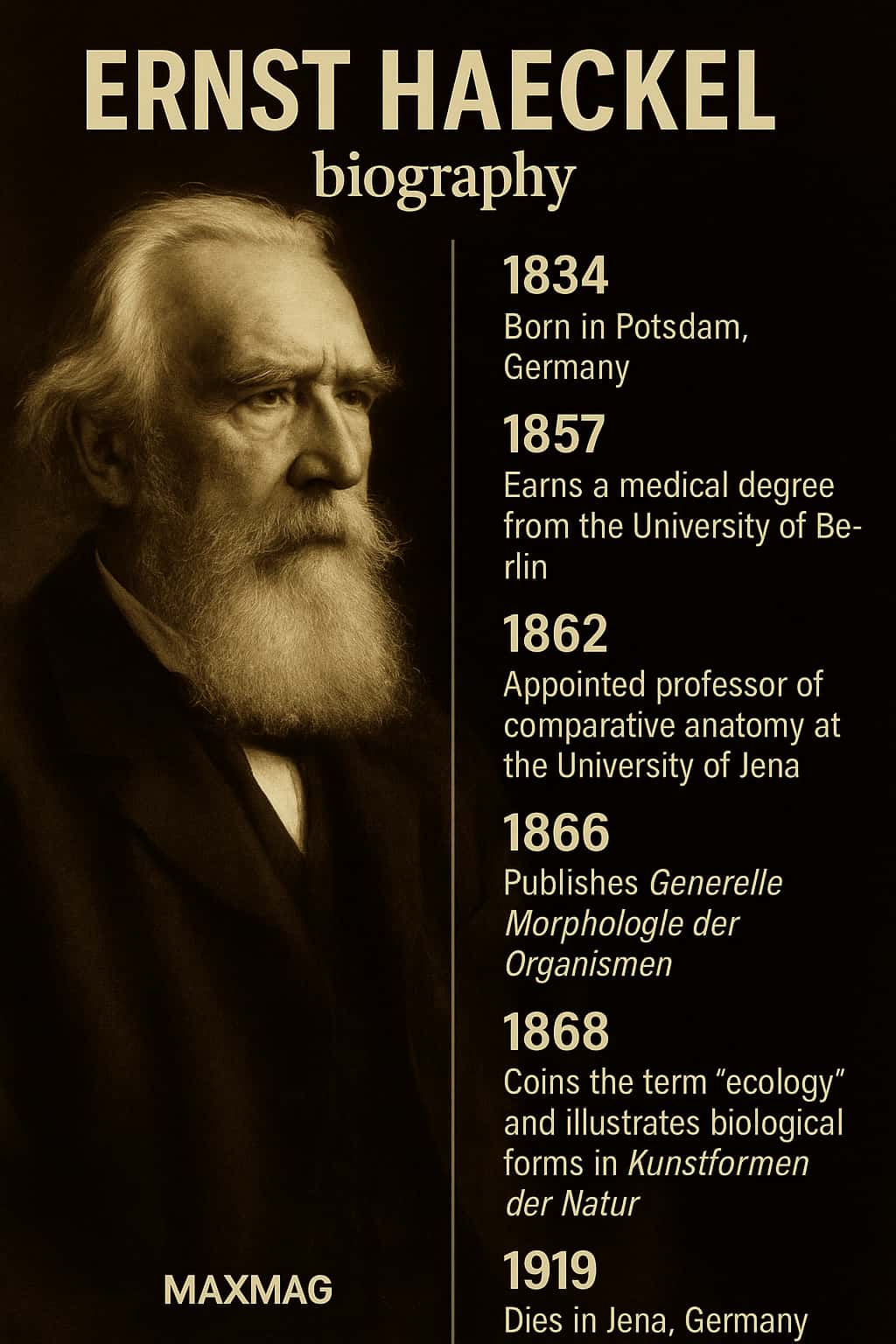

Ernst Haeckel was born in 1834 in Potsdam, then part of Prussia, into a comfortable middle-class family. His father was a legal official, his mother managed the household, and their expectations for their son were solid and respectable: a good education, a professional career, a life of order rather than adventure. Yet from early on, he was drawn much more to shells, plants and insects than to legal codes. Like many future biology pioneers, he spent hours outdoors, collecting specimens and sketching them with a seriousness that made childhood play feel like fieldwork.

Those early sketches would later become a quiet backbone of the Ernst Haeckel biography. They trained his eye to notice pattern and symmetry, the radial delicacy of a jellyfish or the spiky armour of a tiny plankton. At school he proved a capable student, fascinated by languages and the classical curriculum, but his imagination lit up when he could connect textbooks to living organisms he had seen with his own eyes.

Medical training and a restless mind

Following his parents’ wishes, Haeckel enrolled in medical studies in Berlin and Würzburg. Nineteenth-century medicine was closely intertwined with anatomy and physiology, and many of the great biologists of the period began in the clinic. He learned to dissect, to use the microscope carefully, to match symptoms to organs and tissues. For a time, it seemed he would live a conventional life as a physician.

But the hospital wards left him dissatisfied. He found the practical routine of treating patients less compelling than the deeper questions that lurked in the background: What is life? How do organs arise in embryos? How are animals related to each other across vast stretches of time? In the mid-1850s and early 1860s, these were questions hanging over European science, and they would soon give the Ernst Haeckel biography its decisive pivot.

Turning from medicine to zoology

The turning point came when Haeckel travelled to Italy, where the Mediterranean coast offered him both a visual feast and an intellectual escape. Collecting and drawing marine animals in Messina, he realised that his passion was not the doctor’s bedside but the naturalist’s shore and laboratory. The textures of jellyfish bells, the intricate glassy skeletons of radiolarians, and the delicate forms of plankton pulled him away from medical practice and into pure research.

By the time he returned to Germany, he had decided to switch careers. He completed a doctoral thesis on radiolarians, microscopic marine organisms that would recur throughout his life. This risky move – abandoning a secure profession for the uncertain path of a zoologist – established him as an evolutionary biology pioneer just as Charles Darwin’s ideas were beginning to shake the scientific world.

Ernst Haeckel biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

Encountering Darwin and the evolutionary storm

In 1859, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species exploded into scientific and public debate. For a young German zoologist hungry for a unifying theory, Darwin’s work offered an irresistible framework. Haeckel read the book as a revelation. In later writings, he described how natural selection gave him a way to connect his detailed observations of embryos and marine creatures to a grand history of life on Earth.

Many histories of nineteenth-century science emphasise that Haeckel became Darwin’s most vocal champion in the German-speaking world. He wrote popular books, gave fiery lectures, and argued that evolution was the central organising principle of biology. A University of California resource on the early evolution and development work of Haeckel describes how he took Darwin’s relatively cautious ideas and pushed them into new, sometimes controversial domains.

Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny

The slogan most closely associated with Haeckel is “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny”. In plain terms, he argued that an embryo’s development (ontogeny) passes through stages that mirror the evolutionary history (phylogeny) of its species. So a human embryo, for example, seems at certain points to resemble a fish, then a reptile, before taking on recognisably mammalian features. For Haeckel, this was not just a striking visual parallel but a key to understanding how new species arise.

Today, biologists view this recapitulation theory as oversimplified and in many details flatly wrong. Embryos do not literally replay evolution, and the resemblances between stages are much more complex than Haeckel proposed. But in the context of nineteenth-century embryology, when researchers were comparing early development across species for the first time, the idea helped focus attention on the developmental processes that underpin evolution. The Ernst Haeckel biography cannot be told honestly without acknowledging both the power and the failure of this famous phrase.

Drawing evolution: how art shaped the Ernst Haeckel biography

Haeckel’s big ideas were never purely verbal. His notebooks and later publications are filled with plates where the logic of evolution emerges as much from composition as from text. Embryos arranged in parallel rows, radiolarians spiralling across a page, trees of life branching into ever finer twigs – all of these became visual arguments for evolutionary descent. In many ways, the Ernst Haeckel biography is also a history of scientific illustration, showing how images can persuade where words falter.

Those images would eventually reach the public well beyond professional science. Through them, Haeckel shaped how evolution looked in the popular imagination. The secondary keyword “tree of life” was not just a metaphor; it was a literal diagram that readers could trace with their fingers, feeling humanity’s place as one twig among many.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Ernst Haeckel

Generelle Morphologie and the architecture of life

Haeckel’s 1866 book Generelle Morphologie der Organismen (“General Morphology of Organisms”) is often regarded as his most ambitious scientific work. In dense, sometimes daunting prose, he tried to map the architecture of living forms, from cells to entire phyla. It was here that he popularised terms like “phylogeny” and “ecology”, giving later generations of scientists a vocabulary for the history and relationships of life.

For modern readers approaching any Ernst Haeckel biography, Generelle Morphologie can seem remote and abstract. Yet elements of it echo in contemporary systems biology, which also seeks broad patterns behind the immense variety of organisms. Haeckel wanted biology to be more than a catalogue; he wanted it to be a coherent story about how complexity emerges over time.

Kunstformen der Natur: art forms of nature

If Generelle Morphologie was Haeckel’s intellectual fortress, Kunstformen der Natur (“Art Forms in Nature”) was his public gallery. This multi-volume collection of colour lithographs, published between 1899 and 1904, presented jellyfish, radiolarians, moths, bats and countless other organisms in dramatic, almost theatrical arrangements. Haeckel exaggerated certain symmetries and lines, but he grounded his plates in years of microscopic observation.

A Smithsonian Magazine article on his marine illustrations traces how these images influenced not just science but Art Nouveau design, furniture, jewellery and even architecture. In that sense, the journalistic portrait of Haeckel’s sea-creature drawings doubles as a miniature Ernst Haeckel biography, showing how a working scientist became an unexpected design icon.

Die Welträthsel and the leap into philosophy

In 1899, Haeckel published Die Welträthsel (“The Riddle of the Universe”), a book aimed at a broad audience that blended biology, physics, philosophy and religion. Here he argued for “monism”: the view that all reality is fundamentally one substance, and that mind and matter cannot be separated into different realms. Religion, in his telling, should yield to a unified scientific worldview.

The book sold in enormous numbers and made Haeckel a household name, far beyond the circle of professional zoologists. It also intensified the split between admirers who saw him as a fearless free-thinker and critics who accused him of overreaching. The Ernst Haeckel biography thus straddles not only the history of biology but the wider history of European freethought at the turn of the twentieth century.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

The laboratory and the sketchbook

Haeckel’s working method fused patient microscopy with almost obsessive drawing. He would spend long days observing marine organisms – medusae, siphonophores, radiolarians – adjusting mirrors and lenses to coax out details barely visible to the naked eye. Then, often late into the night, he translated those observations into careful sketches and watercolours.

In the Ernst Haeckel biography, this repetition of looking and drawing becomes a kind of rhythm: collect, observe, sketch, refine, publish. It is easy to see him as an evolutionary biology pioneer, but he was also an artisan, crafting his arguments with pen and brush as much as with words and numbers. His approach illustrates how nineteenth-century science relied on personal skill long before automated imaging.

Networks of students and colleagues

As a professor at the University of Jena, Haeckel supervised students, exchanged letters with colleagues, and participated in the dense network of learned societies that characterised nineteenth-century science. He corresponded with Charles Darwin and other leading figures, offering continental support for Darwin’s ideas when they were still under siege in many circles.

Jena became a hub for evolutionary research and debate. Through lectures and seminars, Haeckel trained a generation that would carry embryology and zoology into the twentieth century. Any Ernst Haeckel biography that focuses only on the lone genius misses this collective story of laboratories, classrooms and scientific societies that brought new ideas to life.

The Jena Phyletic Museum: a physical legacy

One of Haeckel’s most concrete contributions was the founding of the Jena Phyletic Museum, an institution dedicated to explaining evolution through specimens and art. Skeletons, fossils, and reproductions of his plates were arranged to tell visitors a story of descent with modification. It was a history of biology laid out in glass cases and wall charts.

The museum still exists, a reminder that the Ernst Haeckel biography cannot be confined to books. It lives on in bricks and mortar, in exhibition halls where schoolchildren and tourists encounter evolution not just as theory but as a visual, spatial experience.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Embryo drawings and allegations of fraud

No discussion of Haeckel can avoid the controversy over his embryo drawings. To illustrate similarities in early development among vertebrates, he produced plates in which embryos of fish, reptiles, birds and mammals appear strikingly alike in their earliest stages. Later critics argued that he exaggerated these similarities, standardising forms and omitting differences to make his evolutionary case appear stronger.

Historians and biologists still debate the extent of his distortions and intentions. Some see deliberate fraud; others see an illustrator simplifying for pedagogical effect in a period before photographic reproduction was routine. Either way, modern textbooks have moved away from reproducing those plates, and the episode has become a cautionary tale about how powerful images can mislead. It remains one of the most uncomfortable chapters in any Ernst Haeckel biography.

Race, social Darwinism and later political shadows

Haeckel’s writings on human races and the application of evolutionary thinking to society have drawn intense criticism. He classified human groups hierarchically and sometimes used language that reduced people to stages on an evolutionary ladder. These views meshed with a broader current of social Darwinism in late nineteenth-century Europe, which attempted to read politics and morality directly off biology.

Later, some ideologues in the twentieth century tried to recruit Haeckel as a precursor of racist and nationalist doctrines, including those of National Socialism. Historians disagree on how direct this line of influence really was, but there is wide agreement that parts of his work contributed to an intellectual climate in which such ideologies could flourish. A responsible Ernst Haeckel biography must place his racial theories in their historical context without excusing them.

The Ernst Haeckel biography as a mirror of nineteenth-century science

Many controversies that swirl around Haeckel today reflect broader tensions in nineteenth-century science: how to balance bold synthesis with careful observation, how to communicate complex ideas to the public, and how to separate empirical findings from sweeping world-views. The Ernst Haeckel biography, read critically, reveals both the strengths and the blind spots of an era that was building modern biology while still entangled in older hierarchies and prejudices.

For modern readers, this makes him a challenging but instructive figure. He reminds us that scientific pioneers can be deeply flawed, and that we can value their insights while rejecting the harmful uses to which they sometimes put their theories.

Impact on Biology and on Wider Society

Popularising evolution in continental Europe

In Germany and beyond, Haeckel became one of the foremost popularisers of Darwinism. His public lectures drew large crowds, his books were translated and reprinted, and his diagrams circulated in classrooms. For many readers, especially in central Europe, their first encounter with evolution came not directly from Darwin but through Haeckel’s fervent interpretations.

As a result, the Ernst Haeckel biography overlaps with the story of how evolutionary theory entered school textbooks, political speeches and philosophical debates. He helped make evolution a central topic in late nineteenth-century science and culture, ensuring that arguments about natural selection and common ancestry were no longer confined to specialist journals.

Influence on art, design and architecture

Beyond science, Haeckel’s drawings had a surprising afterlife in art and design. Artists and architects borrowed motifs from his plates: the radiating spokes of radiolarians, the curling tendrils of jellyfish, the latticed forms of microscopic skeletons. These biological patterns fed into Art Nouveau and other movements that sought inspiration in nature.

This cross-pollination shows how a single Ernst Haeckel biography can spill well outside the laboratory. His work exemplifies how visual culture and scientific illustration can influence everything from wallpapers to building facades, turning the microscopic into everyday ornament.

Shaping concepts in ecology and development

Haeckel famously coined the term “ecology” to describe the study of organisms in relation to their environment. Although the discipline has changed enormously since his time, the basic idea that living things are embedded in networks of interaction remains central. He also helped spread the notion that development and evolution are intertwined questions, a theme that would later re-emerge in evolutionary developmental biology (“evo-devo”).

Secondary keywords like “biology pioneer” and “history of biology” resonate strongly here. Even where his specific theories have been rejected or revised, Haeckel’s framing of questions continues to shape how researchers think about life’s complexity.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Romance, grief and the sea

Behind the public controversies, Haeckel’s private life contained moments of deep joy and intense grief. One oft-told scene in the Ernst Haeckel biography concerns his first wife, Anna Sethe, who died suddenly not long after their marriage. Devastated, Haeckel named a striking jellyfish Desmonema annasethe in her honour and described its trailing tentacles as like “blonde hair ornaments of a princess”.

It is hard to read this passage and not sense how personal loss shaped his emotional connection to the sea and its inhabitants. For him, the marine world was not merely a field site but a place where memory, love and scientific curiosity intertwined.

Philosophical monism and anti-clerical streak

Haeckel’s philosophical stance, monism, rejected a sharp division between mind and matter, body and soul. This put him at odds with religious authorities who saw his ideas as undermining traditional doctrines. His public attacks on organised religion and his promotion of a secular, scientific worldview made him a hero to some freethinkers and a villain to conservative critics.

In many Ernst Haeckel biography accounts, this anti-clerical streak looms large. It coloured his lectures, his correspondence and his public persona. Whether one agrees with his conclusions or not, it is clear that he wanted science not only to explain nature but to reshape how people thought about meaning and morality.

Everyday habits and temperament

Accounts from students and contemporaries describe Haeckel as energetic, sometimes impatient, and rarely shy about his opinions. He enjoyed hiking and sketching outdoors, saw travel as a vital part of scientific life, and relished debates that many might have found exhausting. His letters reveal both warmth towards friends and a sharp tongue for those he considered opponents of progress.

These human details keep the Ernst Haeckel biography from becoming an abstract list of works and theories. They remind us that the creator of meticulous plates and sweeping evolutionary schemes was also a man who laughed, grieved, argued and aged.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Ernst Haeckel

Aging professor and shifting scientific tides

As the twentieth century dawned, biology was changing rapidly. New techniques, from improved microscopy to early genetics, began to challenging some of Haeckel’s formulations. Younger scientists were less interested in grand philosophical systems and more focused on Mendelian inheritance, chromosomes and experiments that could be repeated and quantified.

Haeckel, now an established elder statesman, watched these developments with mixed feelings. He welcomed evidence that strengthened evolution, but he also clung to certain ideas – including strong versions of recapitulation – that were losing favour. The later chapters of any Ernst Haeckel biography capture this sense of a pioneer partly overtaken by the very movement he helped launch.

Retreat, reflection and final works

In his later years, Haeckel spent more time in his house and garden in Jena, surrounded by mementos of his travels and work. He continued to write, revising and re-issuing earlier books, engaging in public debates, and refining his philosophical arguments. At the same time, he struggled with physical ailments and the sense that a new scientific generation saw him as controversial or outdated.

He died in 1919, shortly after the First World War, in a Europe transformed by industrialised conflict and political upheaval. The world of salons, sea voyages and leisurely correspondence that fills much of the Ernst Haeckel biography had vanished. What remained were his books, his plates, his museum and a complicated intellectual inheritance.

The Lasting Legacy of the Ernst Haeckel biography in Modern Science

Between inspiration and warning

Today, scientists and historians approach Haeckel with a mixture of admiration and caution. His extraordinary illustrations still inspire biologists, artists and designers. His efforts to connect evolution, development and ecology anticipated themes that remain vital in twenty-first-century research. Yet his errors and prejudices, especially in embryology and race theory, serve as warnings about the risks of stretching data to fit a grand narrative.

In this sense, the Ernst Haeckel biography functions as a case study in the history of science: a reminder that progress is messy, that pioneers often combine insight with bias, and that no single thinker owns a scientific field. The secondary keyword “Ernst Haeckel legacy” captures this dual character – both a source of enduring ideas and a bundle of problems to confront.

Why Ernst Haeckel still matters

Understanding the Ernst Haeckel biography helps us see how biology became a modern discipline rooted in both careful observation and sweeping historical stories. His life connects microscopic organisms to global philosophies, classroom diagrams to political debates, and the quiet work of drawing to the noisy controversies of public science. When we trace that arc, we gain a clearer sense of how scientific authority is built, challenged and revised.

In an era when images, infographics and viral diagrams shape public opinion about genetics, climate and pandemics, Haeckel’s story feels unexpectedly current. His successes show the power of visual explanation; his failures show how easily that power can mislead. To follow the Ernst Haeckel biography from Potsdam to Jena, from the Mediterranean shore to the pages of philosophy and politics, is to follow the tangled rise of modern science itself.

Frequently Asked Questions about Ernst Haeckel biography

Below are answers to some common questions readers have after encountering the life and work of this influential, controversial biologist.

Q1: Who was Ernst Haeckel and why is he important in biology?

Q2: What does “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” mean in the Ernst Haeckel biography?

Q3: How did Ernst Haeckel biography intersect with Charles Darwin’s ideas?

Q4: Why are Ernst Haeckel’s embryo drawings controversial?

Q5: Where can I see the art featured in the Ernst Haeckel biography today?

Q6: What is the legacy of Ernst Haeckel biography in modern science and culture?