Henri Lefebvre’s reflections on the “everyday life of the city” invite us to reimagine how we inhabit space, time, and social routines. Often overshadowed by more conventional Marxist thinkers, Lefebvre stands out for focusing not on factories or revolutions—but on boredom, routine, sidewalks, and coffee shops. His enduring project was the critique of everyday life Lefebvre developed over decades: a philosophical rebellion against the quiet tyranny of the ordinary.

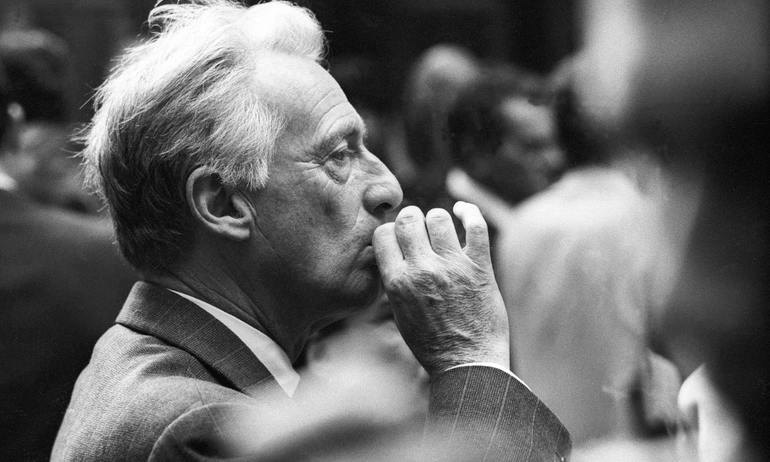

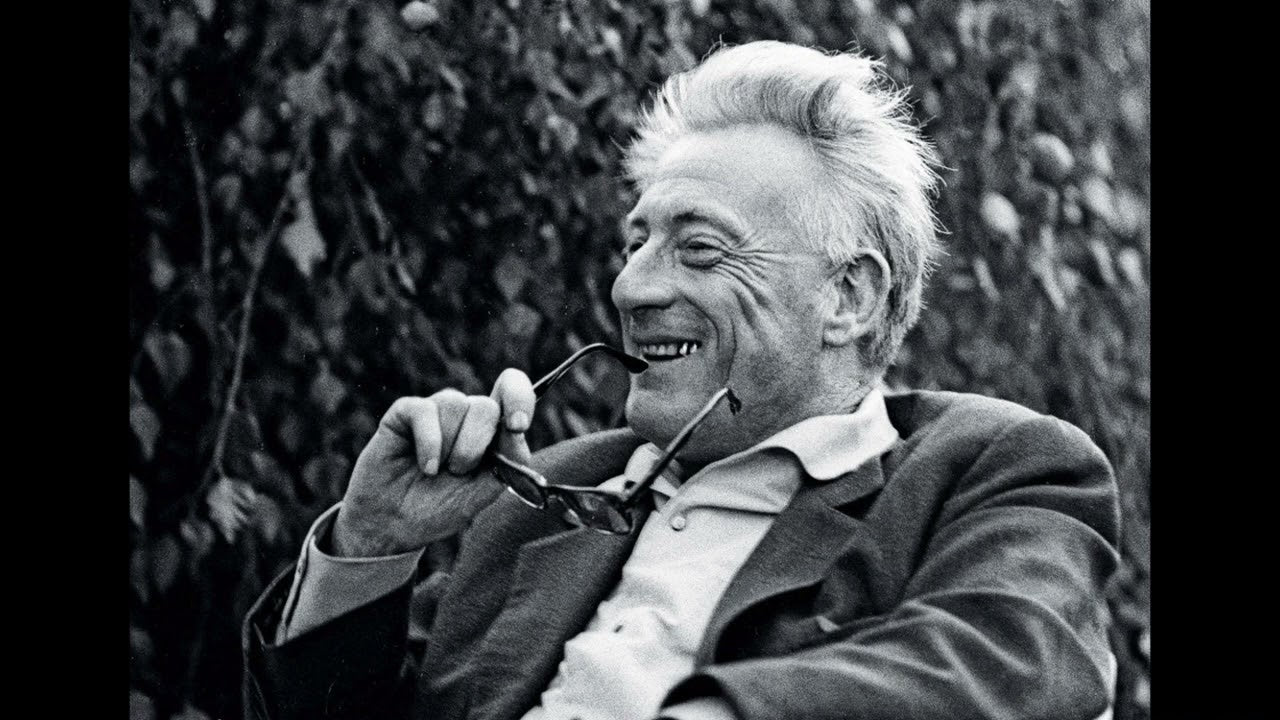

The Man Behind the Theory

Born in southwestern France in 1901, Lefebvre came of age in an era of upheaval and transformation. Initially devoted to literature and poetry, he gradually entered the philosophical world, drawn to Marxist theory but unafraid to deviate from its orthodoxies. His intellectual independence ultimately led to a break with the French Communist Party in 1958. Rather than dwell in ideological abstraction, Lefebvre turned his gaze to the streets—to how people live, where they walk, and how power expresses itself in the most unnoticed dimensions of daily life.

Critique of Everyday Life Lefebvre: A Radical Perspective

Lefebvre’s major intellectual contribution lies in his trilogy Critique of Everyday Life, published across more than three decades (1947, 1961, 1981). In these works, he argued that everyday life is where ideology seeps in most deeply. We often believe that routine is neutral—unchanging, insignificant—but Lefebvre insisted it is where power hides in plain sight.

Under capitalism, even our most mundane choices—what to eat, how to commute, how to relax—are shaped by market forces. The critique of everyday life Lefebvre offers is not cynical; it’s liberating. Once we realize that daily life is socially constructed, we can begin to reimagine it and reclaim agency.

“To change life, we must first change space,” he famously said—suggesting that the fight for liberation is as much about reconfiguring our environments as it is about reshaping laws or economies.

The Colonization of Daily Life by Capital

For Lefebvre, capitalism is not just an economic system; it is a cultural logic that infiltrates our private spaces. Consumerism, advertising, and mediated entertainment are not neutral or harmless. They drain spontaneity from life and replace it with repetition—what Lefebvre called “cyclical time.” The result is alienation, a dulling of the senses.

Rather than creating our own rhythms and rituals, modern individuals adopt those imposed by mass media and corporations. Lefebvre saw this colonization as one of the greatest dangers of modernity, and it formed the backbone of his critique of everyday life Lefebvre.

An excellent example is the shopping mall. Far from being a simple place to purchase goods, it becomes a controlled environment where desires are manufactured, and human interaction is commodified. Similarly, television reshapes how families gather, replacing real conversation with passive consumption.

Urban Space: Power Made Visible

In The Production of Space (1974), Lefebvre extended his theories to geography and urbanism. He argued that space is never just a background. It is produced, organized, and owned. Cities are shaped not only by architects or planners but by financial institutions, legal systems, and political ideologies.

The layout of a city—from roads to zoning laws—serves particular interests. A gated community, a luxury high-rise, or a privatized park reflects deeper social stratifications. Space becomes the medium through which power operates. As part of the critique of everyday life Lefebvre, this insight revealed how even the design of a park bench can reinforce hierarchies.

Think of gentrification—not merely as real estate turnover but as a cultural and spatial transformation that redefines who belongs where.

Lefebvre’s ideas now echo in the practices of urban theorists, planners, and activists across the globe. Organizations like Project for Public Spaces draw upon his work to advocate for inclusive, citizen-centered design.

Reclaiming the Right to the City

In his 1968 work Le Droit à la ville (The Right to the City), Lefebvre called for more than reform: he envisioned a radical reinvention of urban life. The city, he claimed, should not be a tool of capitalism or surveillance. It should be a space for play, creativity, and encounter.

The critique of everyday life Lefebvre puts forth in this book has been foundational for movements like Occupy Wall Street and grassroots urban initiatives worldwide. From participatory budgeting to car-free zones, his influence is visible in modern efforts to reclaim cities for the people who live in them—not just those who profit from them.

This idea has taken root in American urban justice movements, like those supported by The Center for Community Progress, advocating for equitable development and resisting displacement.

Resistance and Renewal in Everyday Life

Despite his bleak diagnoses, Lefebvre was not a pessimist. He believed that everyday life, once recognized as a terrain of struggle, could also become a site of renewal. Resistance doesn’t require grand gestures. It may appear in the way people organize neighborhood potlucks, reclaim public squares, or defy consumerist logic by creating art, gardening, or simply pausing for real conversation.

By recognizing the constructed nature of routines, individuals and communities can begin to reassert their rhythms and values. This is the optimistic core of the critique of everyday life Lefebvre: the possibility of transforming alienated routines into creative practices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Who was Henri Lefebvre?

Henri Lefebvre was a French Marxist philosopher and sociologist known for his work on everyday life, urban theory, and space. He was one of the first to analyze how capitalism influences daily routines and public environments.

What is the “critique of everyday life”?

It’s a framework developed by Lefebvre to analyze how capitalist systems infiltrate and shape our daily routines. It argues that mundane life—meals, leisure, conversations—is a key site of ideological control and potential resistance.

Why is urban space important in Lefebvre’s theory?

Lefebvre believed that space is socially produced and reflects power relations. Cities are not neutral; they are structured in ways that serve specific economic and political goals.

What does “right to the city” mean?

It refers to the idea that all urban residents—not just the wealthy or powerful—should have access to the resources, design, and participation in the shaping of their cities.

How can we apply Lefebvre’s ideas today?

His work encourages us to re-examine our routines, reclaim public spaces, and resist consumerist norms. Movements for walkable cities, community gardens, and co-housing all resonate with his vision.

Conclusion

Henri Lefebvre challenges us to look where we least expect to find power: in the everyday. His work invites not just scholars and city planners but all of us to examine the rhythms that govern our lives. The critique of everyday life Lefebvre proposed is as relevant now as it was half a century ago, offering tools to understand—and reshape—the cities we live in and the lives we lead.