The Carl Linnaeus biography often begins with a boy in a Swedish parsonage, quietly dismantling flowers as if they were intricate toys. In the early 18th century, when most people knew only the plants that fed or cured them, this child was already treating petals and stamens as clues in a grand puzzle. Decades later, that same boy would be celebrated and criticised in equal measure as the man who tried to bring order to the living world by giving every species a Latin name.

Any Carl Linnaeus biography has to grapple with a double legacy. On the one hand, he was a botany pioneer who gave scientists a common language and helped make modern biology possible. On the other, some of his categories – especially his views on human “varieties” – helped lay foundations for ideas that would later be weaponised in racist theories. Between those two poles lies the real story: a driven, sometimes stubborn Swedish scientist who believed that naming nature was the first step to understanding it.

At a glance:

- Who: Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), Swedish botanist, physician and naturalist.

- Field and era: Botany and taxonomy during the age of Enlightenment science.

- Headline contributions: Developed the Linnaean system of classification and popularised binomial nomenclature for naming species.

- Why he matters today: His taxonomy history shapes how biology, conservation and natural history museums still organise life on Earth.

Early Life and Education of Carl Linnaeus

To understand the Carl Linnaeus biography, it helps to start in Råshult, a small village in southern Sweden. Born in 1707, Carl was the son of a Lutheran pastor who loved gardening almost as much as scripture. The parsonage grounds were packed with flowers, herbs and fruit trees, and young Carl learned their names as other children learned nursery rhymes. Plants, for him, were never just scenery; they were companions with identities waiting to be discovered.

School, however, was less enchanting. Linnaeus struggled with the classical curriculum, full of rhetoric and theology. His teachers dismissed him as a weak student and steered him towards a manual trade. One sympathetic master noticed the boy’s passion for plants and recommended that he study medicine instead, which at the time was deeply entangled with botany. That suggestion quietly altered the course of the Carl Linnaeus biography.

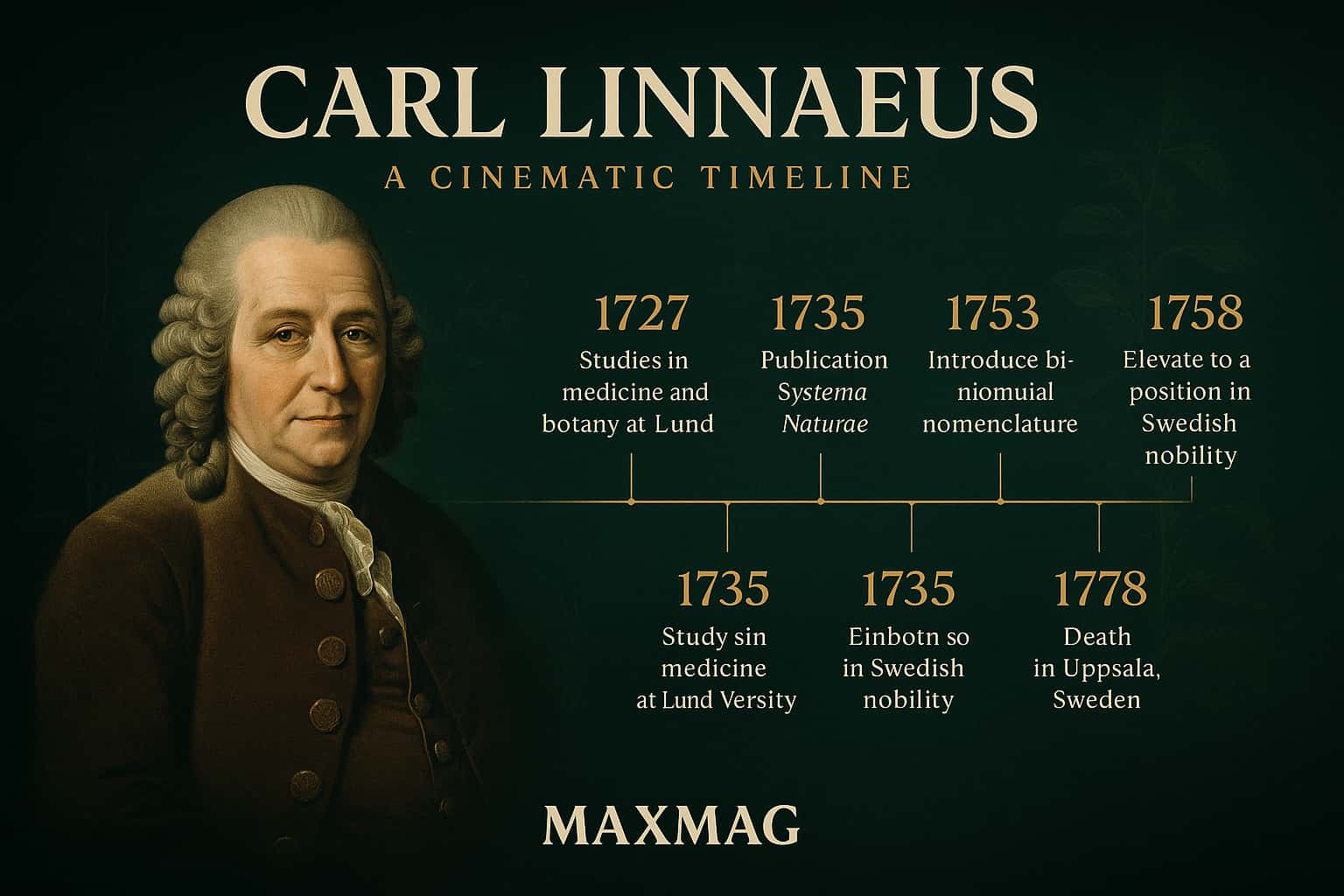

At the universities of Lund and later Uppsala, Linnaeus found his world expanding. Sweden’s emerging scientific community was small but ambitious, eager to be part of the wider European conversation in natural history. At Uppsala, he haunted the botanical garden and began sketching out his own ideas on how plants might be grouped by their reproductive organs – a daring move in a culture that still viewed sexuality as something to be downplayed, not dissected in public lectures.

There was nothing inevitable about his rise. Linnaeus depended on the patronage of senior scholars and wealthy supporters who lent him rooms and resources, sometimes in exchange for tutoring their children. In these precarious years, he learned to navigate the social side of Enlightenment science: flattery, dedication letters, and the careful management of professional rivalries. The shy boy from Råshult was becoming a confident participant in the history of biology.

By the time he completed his medical degree in the Netherlands, Linnaeus had a clear goal: to create a systematic, usable way of naming and classifying the teeming diversity of life. The seeds of the future Carl Linnaeus biography – the image of the scientist who named nature – had already been planted in those student gardens and lecture halls.

Carl Linnaeus biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

The section of any Carl Linnaeus biography that covers his big ideas usually begins not in a library, but on the road. In 1732, Linnaeus set out on a long, harsh journey through Lapland in northern Sweden, commissioned to document plants, animals and minerals. He walked for months through bogs and forests, sleeping in rough huts and eating whatever he could find. It was fieldwork on a scale few naturalists of his time attempted.

On that Lapland expedition, Linnaeus saw how chaotic nature could seem when you were knee-deep in it. He encountered plants that looked similar but were not, and insects that shared features but behaved differently. This was taxonomy history written in mud and mosquito bites. He realised that if natural history was to move beyond mere curiosity, it needed a clear structure – a way to say, with some precision, what counted as the same species and what did not.

From these experiences emerged the Linnaean system. Linnaeus proposed that all living things could be organised into nested groups – species, genera, families, orders, classes and kingdoms – based on shared characteristics. It was like designing a set of labelled drawers for the living world, each species a file in the right compartment. For an era hungry for system and order, this spoke directly to the spirit of Enlightenment science.

Reading the Carl Linnaeus biography as a story of classification

Seen through a modern lens, the Carl Linnaeus biography is a case study in how a simple idea – grouping organisms by shared traits – can transform an entire field. Before Linnaeus, natural history was a patchwork of local naming traditions and private catalogues. After him, scientists across Europe could speak a common language about species, even when they disagreed about deeper questions such as how life began or whether it changed over time.

Another crucial element was binomial nomenclature, the two-part naming system that still underpins modern biology. Linnaeus suggested that every species should have a generic name (its genus) and a specific epithet (its species). Homo sapiens, for instance, would be just one species within the genus Homo. This innovation made species names shorter, more stable and easier to compare. In the crowded marketplace of Enlightenment ideas, this particular invention has outlived almost everything else.

At the time, Linnaeus saw himself less as an original theorist and more as an organiser. He referred to himself, half-modestly, as “a clerk of nature”. The Carl Linnaeus biography, then, is not about sudden flashes of inspiration, but about the patient labour of sorting, grouping and renaming – a kind of intellectual bookkeeping that turned out to be revolutionary.

By the mid-18th century, his classification scheme had attracted both followers and critics. Some naturalists resented his focus on reproductive organs, finding it indelicate or too narrow. Others worried that his tidy system glossed over the complexity of living things. Yet even many critics still used his categories in practice. Linnaeus had reshaped the chessboard on which the debates of biology would be played.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Carl Linnaeus

No Carl Linnaeus biography is complete without a close look at his books. His most famous work, Systema Naturae, began as a slim pamphlet in 1735 and grew into a multi-volume catalogue of the known living world. It was updated repeatedly during his lifetime, reflecting new discoveries sent by students and correspondents from distant colonies. Each new edition made his classification more detailed and, in many minds, more authoritative.

Alongside this stood Species Plantarum, published in 1753, which systematically described plant species using the binomial names that would become standard. Modern botanists still treat that book as the starting point for official plant nomenclature. When conservationists or researchers today argue over the status of a rare plant, they often trace its name back to a decision Linnaeus made in those pages.

He also wrote textbooks that functioned as teaching tools for generations of students. These works were not just lists; they contained condensed lectures on how to observe, classify and describe. In an age before online databases and digital herbariums, Linnaeus’s books were a kind of portable infrastructure for scientific knowledge, carried in the luggage of travellers and stashed on the shelves of universities and academies.

How the Carl Linnaeus biography intersects with his great books

In many ways, the Carl Linnaeus biography is inseparable from the publication history of these volumes. Each new edition of Systema Naturae marked a milestone in his status. Early versions were printed in small runs for a relatively narrow circle. Later ones spread across Europe and beyond, making his system the default starting point for anyone serious about natural history. The evolution of his books mirrors the rise of a new scientific culture that valued standardisation and reference.

His works also helped tie Sweden into a global network of science. As students trained in Uppsala travelled to places like North America, South Africa and East Asia, they sent back specimens and reports, adding material to their mentor’s classifications. Modern natural history museums, including major institutions such as the Smithsonian Institution, still house collections that reflect this Linnaean impulse to gather, label and compare.

From a distance, these achievements can look almost bureaucratic. But to contemporaries, they were thrilling. Linnaeus had given scholars a ladder to climb into the dizzying diversity of life. His key works transformed disorganised cabinets of curiosities into something closer to a global catalogue, a foundation on which later biology and ecology could build.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

The Carl Linnaeus biography is not just a list of books and dates; it is also a story about how science was done in the 18th century. Linnaeus was both a field naturalist and a desk worker, comfortable trudging through wetlands and just as comfortable surrounded by dried specimens. He relied heavily on careful observation, often stressing that students should trust what they could see and dissect rather than inherited descriptions.

At Uppsala University, he turned his lectures into performances. Students later recalled how he would walk them through the botanical garden, stopping at each bed to explain how a plant fit into his system. He used the garden itself as a living diagram of his taxonomy, a teaching approach that feels surprisingly modern. For many young scholars, their personal Carl Linnaeus biography began in those outdoor lessons, under the Nordic sky.

Collaboration was central to his work. Linnaeus trained a cohort of “apostles” – talented students he sent around the world to collect plants and animals. These apprentices travelled to places as far-flung as Japan, West Africa and the Caribbean, sometimes at great personal risk. Their letters and specimens poured back into Uppsala, allowing Linnaeus to expand his system far beyond the species he had personally seen.

In practice, this meant that Linnaeus’s methods blended solitary analysis with a loose, global network of observers. He treated his students as extensions of his own eyes, trusting their descriptions but ultimately reserving the final judgment on how a new species should be named. It was an early, imperfect version of a research group, with Linnaeus as principal investigator.

His working style could be intense. Accounts from colleagues mention a man who rose early, worked late and sometimes neglected other duties in his fixation on classification. Yet he also maintained a busy medical practice for part of his career, treating patients and writing prescriptions. In a way, the tension between healing individual bodies and cataloguing the living world is one of the quieter threads running through the Carl Linnaeus biography.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

No serious Carl Linnaeus biography can ignore the controversies attached to his name. The most troubling centre on his classification of humans. In later editions of Systema Naturae, Linnaeus divided Homo sapiens into “varieties” based largely on geography and physical traits. While he did not rank these human groups as explicitly as some later thinkers, his work helped normalise the idea that humanity could be carved into biological categories tied to perceived character traits.

These categories became raw material in the nineteenth century for racial theories that claimed a scientific basis for hierarchy. It would be unfair to blame that entire history on Linnaeus, but equally unfair to treat his classification of human varieties as a harmless quirk of taxonomy. Modern historians of science often position him as an early, complicated figure in the genealogy of scientific racism.

He also attracted criticism from other naturalists who disagreed with his methods. The French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, for example, disliked rigid systems and argued that living things were shaped by their environments in ways that resisted neat classification. Their debate helped sharpen the larger questions of biology and showed that Enlightenment science was not a monolith but a field of competing visions.

Myths and oversimplifications in the Carl Linnaeus biography

Over time, a few myths have attached themselves to the Carl Linnaeus biography. One is that he single-handedly created the idea of species. In reality, earlier thinkers had already spoken of species, but with less precise definitions. Linnaeus’s real contribution was to give the concept a practical, repeatable form through binomial nomenclature and hierarchical grouping.

Another misconception is that his system remains unchanged. In fact, modern systematics, guided by genetics and evolutionary theory, has dramatically reshaped many branches of the tree of life. Whales are no longer grouped with fish, and birds are recognised as living dinosaurs. Yet even as scientists revise the branches, they still use Linnaean ranks and Latin names as a shared scaffold. It is a reminder that the Carl Linnaeus biography is not a museum piece but part of an ongoing conversation about how we map life.

Recognising these nuances does not erase his problematic ideas, but it allows us to see him as a product of his time and as someone whose work took on meanings he could not have predicted. That complexity is where many modern readers find the most value.

Impact on Biology and on Wider Society

The impact of the Carl Linnaeus biography reaches far beyond the pages of his books. By standardising names, he made it possible for scientists in different countries to know they were talking about the same species. This sounds simple, but it transformed everything from medicine to agriculture. A plant known by half a dozen folk names could now be pinned down to a single Latin binomial, helping physicians avoid dangerous confusion and botanists share reliable information.

His system also helped natural history museums and botanical gardens become more than just curiosity cabinets. They could now organise their collections in a way that told clear stories about relationships between species. Many institutions still label exhibits with Latin names rooted in Linnaeus’s decisions, even when the underlying evolutionary relationships have been updated by DNA studies and phylogenetics.

Outside professional biology, Linnaeus shaped how ordinary people encounter nature. Field guides, wildlife documentaries and even smartphone apps that identify plants are built on the assumption that each species has a stable name. That assumption, born from Enlightenment science and the Linnaean system, helps anchor public debates about conservation and biodiversity loss. It is easier to worry about the fate of a species when it has a clear identity.

Modern science journalism, including outlets such as the New York Times science section, still relies on this taxonomic backbone when explaining everything from emerging diseases to climate-threatened ecosystems. Species names act as coordinates in a vast map of life, and Linnaeus was one of the first to draw the grid.

In this sense, the Carl Linnaeus biography is not only about a Swedish scholar; it is also about how classification quietly shapes public understanding of science and the environment.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

The formal achievements of the Carl Linnaeus biography can obscure the man’s more intimate side. Linnaeus was, by most accounts, devoutly religious. He saw the natural world as a reflection of divine order and often described his work as uncovering the patterns set by a creator. For him, taxonomy was not an attempt to control nature but to read it more clearly.

He married Sara Elisabeth Moraea, the daughter of a prominent physician, and together they had several children. Family life unfolded alongside his academic duties, with children sometimes drafted into helping in the garden or sorting specimens. His surviving letters suggest a man who could be affectionate and proud, especially when one of his sons followed him into botany.

Linnaeus’s personality was not universally charming. Some contemporaries found him vain or overly protective of his ideas. He was keenly aware of his status as a Swedish scientist on an international stage and could react sharply to perceived slights. Yet students often remembered him as inspiring and generous with his time, particularly when discussing botany.

Domestic scenes in Uppsala – dinners with visiting scholars, long evenings in a study filled with dried plants and handwritten notes – form the quieter backdrop to the more dramatic episodes of travel and discovery. They remind us that the Carl Linnaeus biography is as much about a working household as about a lone genius.

His private faith and his public science were not separate domains. For Linnaeus, classification was a way of honouring what he saw as a designed universe. That conviction gave him confidence, but it also made it harder for him to accept ideas that challenged his sense of fixed order, such as the possibility that species might change over time.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Carl Linnaeus

In his later years, the Carl Linnaeus biography shifts from energetic exploration to a slower rhythm. By the 1760s, he was an established figure at Uppsala, his fame extending well beyond Sweden. Honours poured in: foreign academies elected him as a member, and visitors came from across Europe to meet the man who had named so much of nature.

Age, however, brought health problems. Linnaeus suffered from strokes that gradually limited his ability to work. As his physical strength declined, he delegated more teaching and research to his students and family members. The man who had once traversed Lapland on foot now spent more time in his beloved garden, moving slowly among the beds he had arranged so carefully.

There is a quiet poignancy in these final chapters. The world of science was already beginning to move beyond some of his assumptions. Ideas about the mutability of species were circulating, and political changes in Europe were reshaping the networks of empire and exploration that had fed his taxonomy. Yet Linnaeus remained convinced of the enduring value of his system, and in many respects he was right.

He died in 1778, leaving behind not just books and specimens but a way of thinking about life that would outlive him by centuries. The closing scenes of the Carl Linnaeus biography – a respected professor fading from public view – stand in contrast to the continued prominence of his methods in modern biology.

The Lasting Legacy of Carl Linnaeus biography

Today, the lasting legacy of the Carl Linnaeus biography can be felt in classrooms, laboratories and protected forests around the world. Every time a new species is described and given a Latin binomial, it adds another leaf to a tree of life first formalised in Linnaean terms. Even though evolutionary theory and genetics have transformed our understanding of how that tree grew, the basic language of genus and species remains.

His influence also lives on in debates over how to balance stability and change in scientific names. Taxonomists regularly argue about whether to rename species when new genetic data rearrange their relationships. At the heart of those arguments lies a question Linnaeus would recognise: what matters more, preserving a familiar label or updating our maps of nature to reflect new knowledge?

Why the Carl Linnaeus biography still matters in the age of genomics

In the age of DNA sequencing and big data, it might seem strange that a system devised in the 1700s still anchors biology. Yet that is precisely why the Carl Linnaeus biography continues to attract attention. His classification gave scientists a shared starting point, making it possible to plug genetic and ecological information into an existing framework rather than building a new one from scratch.

Beyond science, Linnaeus’s story raises questions about how knowledge is shaped by culture and power. His work depended on specimens gathered from colonised lands, and his human classifications intersected with emerging ideas about race. Understanding this history helps us see modern biology more clearly – not as a purely neutral enterprise, but as a human project with roots in specific times and places.

That, ultimately, is the enduring value of the Carl Linnaeus biography. It invites us to look at the names on museum labels, in field guides and in scientific papers, and to ask who chose them, why they were chosen, and how they continue to shape our view of life on Earth.

Frequently Asked Questions about Carl Linnaeus biography

Q1: Who was Carl Linnaeus and why is he important in biology?

Q2: What is binomial nomenclature and how did Linnaeus use it?

Q3: How did the Carl Linnaeus biography influence later scientists like Charles Darwin?

Q4: Why is Carl Linnaeus criticised for his ideas about human races?

Q5: Did Carl Linnaeus do much fieldwork himself, or mainly work from books?

Q6: Where can I see the legacy of Carl Linnaeus today?