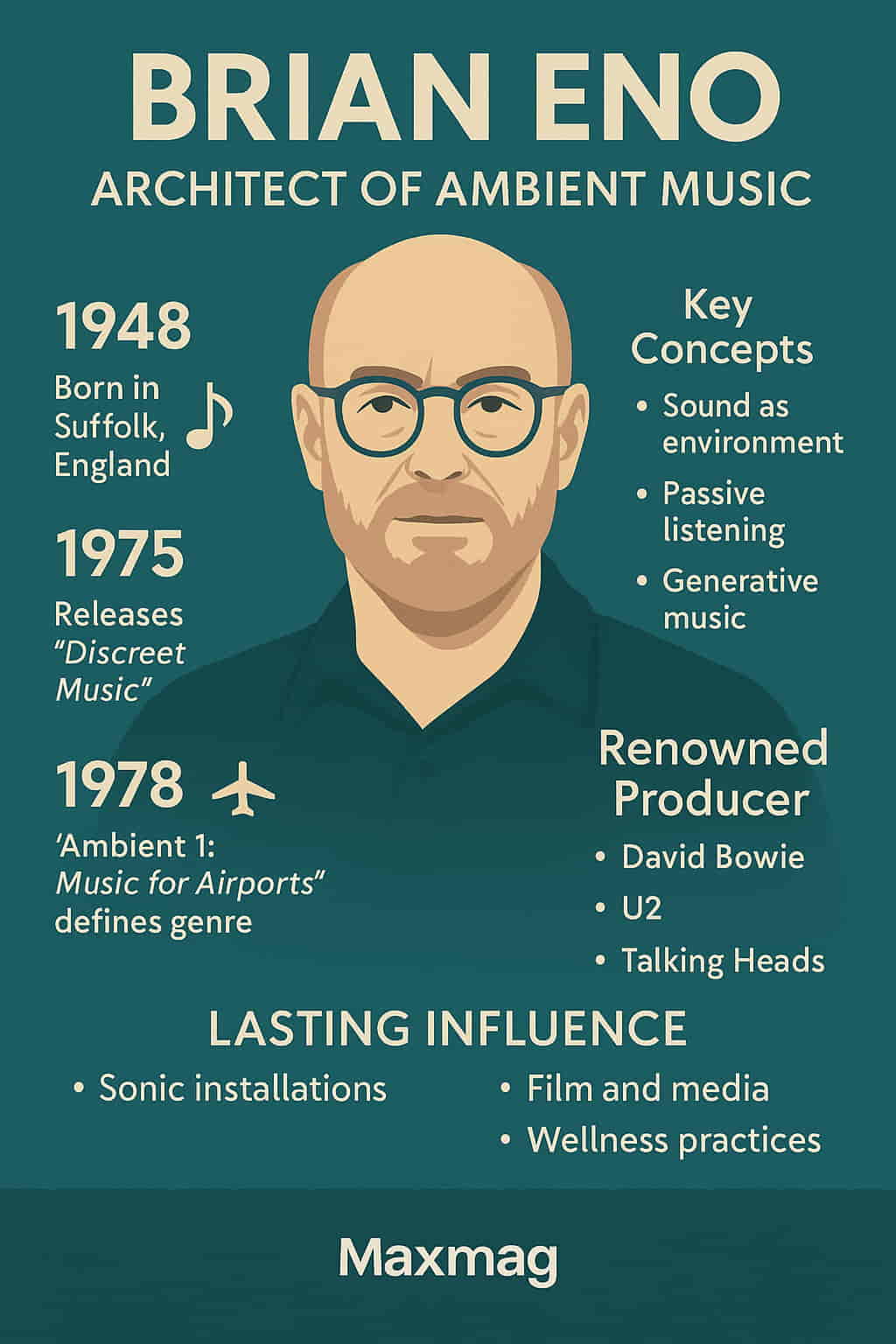

Brian Eno’s name is more than a footnote in music history—it’s a towering symbol of experimentation, innovation, and artistic vision. As a composer, producer, visual artist, and thinker, Eno has blurred the lines between sound and silence, between art and life. With each project, he invites audiences to listen, not just hear—to be immersed in experiences instead of being told what to feel. Central to his enduring legacy is what we now call Brian Eno ambient music: a genre, philosophy, and creative method that reshaped not only music but how we interact with space, time, and emotion.

From his early days with Roxy Music to producing U2, David Bowie, and Talking Heads, to creating sonic installations and generative music apps, Eno has repeatedly challenged conventions. He treats music like a landscape—something to inhabit rather than consume. Let’s explore the life and impact of this artistic polymath and unpack how Brian Eno ambient music has become a cornerstone of 21st-century sonic culture.

Early Life: The Making of an Experimental Mind

Brian Peter George St John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno (yes, that’s his full name) was born in 1948 in Woodbridge, Suffolk. His father repaired clocks and his mother was a devout Catholic with a flair for singing, laying the groundwork for both scientific curiosity and artistic sensibility. Growing up in post-war England, Eno was surrounded by radios, amateur music-making, and a growing interest in modern art.

But it wasn’t until he entered Ipswich Art School and later Winchester School of Art that Eno truly began to question the structures of traditional music. He was drawn not to pop bands or orchestras, but to avant-garde composers like John Cage and minimalist artists like La Monte Young. These influences taught him that art could be interactive, that process could matter more than product, and that sound itself could be manipulated in entirely new ways.

Eno began experimenting with tape machines, feedback loops, and found sounds. Rather than learning to play instruments in the traditional sense, he approached sound as texture and design. These foundations would one day give birth to Brian Eno ambient music, a genre rooted in experimentation, chance, and subtlety.

The Roxy Music Chapter: Embracing Eccentricity

Eno’s first taste of public success came when he joined Roxy Music in 1971. Though not a trained musician, he became the band’s sonic architect, manipulating synthesizers, tape delays, and various effects during live shows. Dressed flamboyantly, often overshadowing frontman Bryan Ferry in visual appeal, Eno helped shape the band’s glam-art sound.

Despite creative success, tensions with Ferry prompted Eno to leave the band in 1973 after two albums. But this was a blessing in disguise. Eno was now free to pursue his artistic ambitions on his own terms—without compromise or constraint.

His early solo albums (Here Come the Warm Jets, Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy) fused rock with abstract textures and proto-punk energy. Yet even these works hinted at a broader artistic vision—one that would come to full expression in the formation of Brian Eno ambient music.

Defining a New Genre: Brian Eno Ambient Music

In 1975, a life-altering moment occurred. After an accident that left him bedridden, Eno listened to a record of harp music at a very low volume. He realized the music mixed with the ambient sounds of the room—the rain, distant cars, creaking furniture—and created a new kind of listening experience. It wasn’t active listening, but passive immersion. The idea of music as an environmental texture—not demanding attention, but coexisting with one’s surroundings—took root.

This epiphany gave birth to Discreet Music (1975), followed by Ambient 1: Music for Airports (1978). These albums laid the groundwork for what is now widely known as Brian Eno ambient music: compositions designed not to entertain, but to enhance atmosphere. Unlike classical music or rock, ambient tracks often lack a beat, traditional melody, or dramatic arcs. Instead, they slowly evolve, encouraging introspection and calm.

Eno didn’t just create ambient music—he defined it. He introduced the term “ambient music” in liner notes and interviews, establishing a language that would inspire generations of composers, film scorers, and even wellness practitioners.

Brian Eno Ambient Music and Its Expanding Influence

The philosophy behind Brian Eno ambient music has reached far beyond the arts. Airports, hospitals, yoga studios, and even meditation apps now incorporate ambient compositions to ease tension, reduce stress, and create harmonious environments. Eno’s vision proved ahead of its time—decades before mental wellness became a mainstream priority.

His ambient work found its way into films, galleries, and installations. Museums such as The Tate Modern and The Museum of Modern Art have featured his sonic and visual exhibitions. In these spaces, visitors don’t merely look at art—they walk through soundscapes. Eno designs experiences that shift perception and slow down time.

Eno’s influence also shaped the emerging genre of generative music—pieces created by systems that evolve over time without human intervention. Eno’s own generative apps like Bloom, Trope, and Scape let users co-create ambient landscapes, reinforcing the idea that ambient is not just for listening—it’s for living.

A Masterful Producer: Elevating Other Artists

While his solo work defined a genre, Eno’s collaborations elevated mainstream music. His partnership with David Bowie on the “Berlin Trilogy” (Low, Heroes, Lodger) helped Bowie transition from glam rock to experimental icon. Eno introduced Bowie to tape loops, non-linear composition, and minimalist structures—techniques drawn directly from his ambient toolkit.

Eno also became a guiding force for U2. As co-producer of The Unforgettable Fire, The Joshua Tree, and Achtung Baby, he infused atmospheric layering into their rock sound, balancing intimacy and scale. These albums became some of the most influential in modern music history.

With Talking Heads, Eno pushed the boundaries of punk and funk. On Remain in Light, he and David Byrne explored polyrhythms and electronic textures, blending African rhythms with ambient sensibilities. This album laid the groundwork for the ‘worldbeat’ genre and remains one of the most innovative albums of the 1980s.

Visual Arts, Books, and Public Thinking

Eno is not just a composer—he’s a philosopher of creativity. His visual art installations, often involving lights and slow-moving images, mirror his ambient soundscapes. His book A Year with Swollen Appendices (1996) blends diary entries with essays on music, technology, and politics.

He frequently speaks at art forums, tech conferences, and cultural summits. His topics range from climate change to artificial intelligence. In all these talks, he champions collaboration, unpredictability, and “scenius”—a term he coined to describe collective genius rather than individual brilliance.

In recent years, he has collaborated with physicists, AI engineers, and activists to explore how music and data can inform environmental awareness. One such project involved mapping deforestation using soundscapes derived from satellite data.

Recent Projects and the Living Legacy of Eno

Eno continues to create into his 70s with the same vigor that marked his early years. His 2022 album FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE focused on climate anxiety and spirituality. Its ambient qualities were darker, colder—designed to evoke reflection in an age of ecological uncertainty.

In 2024, Gary Hustwit premiered the documentary Eno, a generative film where each screening is unique. This revolutionary cinematic approach mirrors Eno’s generative philosophy and marks a first in documentary filmmaking. Every audience sees a different Eno, hears a different story.

His continued work with Lightform (projection-mapping software) and art-science labs reflects a restless mind, constantly reinventing form and content. Eno doesn’t just make music—he makes tools for perception.

The Enduring Power of Brian Eno Ambient Music

Today, Brian Eno ambient music is foundational to film soundtracks, video game scores, sleep playlists, and immersive wellness programs. Artists from Aphex Twin to Jon Hopkins, from Björk to Max Richter, credit Eno as a primary influence.

Music therapists use ambient sound to help patients with anxiety and PTSD. Educators play ambient tracks to help students concentrate. Architects consult sonic designers to tune the acoustic mood of public spaces—often citing Eno’s work as the standard.

His sound, once considered fringe or “background,” is now recognized as profoundly human. Ambient music doesn’t shout; it listens.

FAQ

What is Brian Eno best known for?

He is best known as the pioneer of ambient music and a groundbreaking producer for artists like David Bowie, U2, and Talking Heads.

How did Eno define ambient music?

He defined it as music that is “as ignorable as it is interesting”—designed to enhance an environment without overtaking it.

What tools does he use for generative music?

Eno uses software systems, tape loops, and mobile apps like Bloom to create ever-evolving soundscapes.

Has he written any books or theory?

Yes. His book A Year with Swollen Appendices is part diary, part creative manifesto. He also frequently lectures on art, science, and culture.

Is Brian Eno still making music?

Absolutely. His most recent projects include ambient albums, visual exhibitions, and the first generative documentary film (Eno, 2024).