In the early nineteenth century, if you wanted to understand the planet, you did not reach for a textbook – you reached for Alexander von Humboldt. Today, the Alexander von Humboldt biography reads like a prequel to our own age of climate anxiety: a story about a restless Prussian aristocrat who crossed jungles and volcanoes to prove that nature is not a collection of objects, but an interconnected web of life.

He measured air pressure on Andean summits, sketched rivers from dugout canoes, talked politics with presidents and poets, and warned that deforestation and plantations could change the climate. In his lifetime he was celebrated from Paris to Philadelphia as a scientific explorer, a founder of ecology and an early climate change pioneer. In ours, his name has faded, even as his ideas quietly structure modern environmental thought.

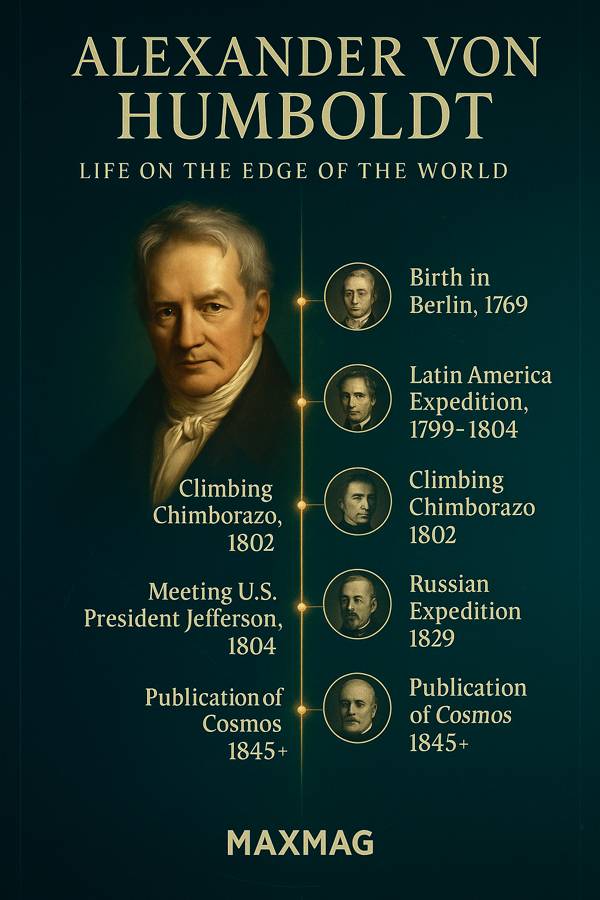

Alexander von Humboldt at a glance

- Who: Prussian naturalist, geographer and explorer (1769–1859).

- Field and era: Late Enlightenment and Romantic science; a bridge between eighteenth-century classification and modern ecology.

- Headline contributions: Pioneered the geography of plants, mapped climate zones with isothermal lines, popularised the idea of nature as an interconnected system, and anticipated human-driven climate change.

- Why he matters today: His holistic, “Humboldtian science” underpins environmental history, climate science and sustainability debates in the twenty-first century.

Early Life and Education of Alexander von Humboldt

Berlin childhood in a divided household

Alexander Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich von Humboldt was born in Berlin in 1769, into a noble but emotionally cold Prussian family. His father, an army officer and court official, died when the boy was nine, leaving Alexander and his older brother Wilhelm under the strict rule of their calculating mother. Tutors drilled the brothers in languages and philosophy, but Alexander preferred sketching plants, collecting insects and wandering the countryside with a sample box – early signs of the restless, empirically minded naturalist he would become.

From bored bureaucrat to underground scientist

Obedient to family expectations, Humboldt trained not as an explorer but as a mining official. He studied at the Freiberg School of Mines in Saxony, immersing himself in geology, chemistry and the physics of gases at a time when mining accidents and toxic fumes made such knowledge literally vital. In his twenties he inspected mines, reorganised operations and – unusually for a nobleman – founded a school to educate miners, a sign of the social conscience that runs through the Alexander von Humboldt biography. In the shafts beneath Freiberg he experimented with underground plants, gas measurements and ventilation, producing early work on plant physiology and the chemistry of air.

Intellectual formation in the age of Kant and Goethe

At university in Göttingen and later in Jena and Berlin, Humboldt encountered the ideas of Immanuel Kant on physical geography and the Romantic poets who saw feeling and imagination as part of knowledge. He befriended Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who encouraged his interest in the “metamorphosis” of plants – how form and function changed across environments. These encounters mattered. They pushed Humboldt beyond narrow technical training towards a bold vision: a science that would combine rigorous measurement with a sense of nature as a living whole, an ambition that would drive the entire Alexander von Humboldt biography.

By his early thirties, Humboldt had savings from his inheritance, a head full of Enlightenment theory and Romantic philosophy, and a growing impatience with office life. The stage was set for the voyage that would change both his life and the history of environmental science.

Alexander von Humboldt biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

How Latin America reshaped the Alexander von Humboldt biography

In 1799, Humboldt left Europe with the French botanist Aimé Bonpland on what would become a five-year expedition through the Spanish Americas. They climbed Tenerife’s Pico del Teide, navigated the Orinoco and its tributaries in a carved canoe, crossed the Andes at extreme altitude and travelled through today’s Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Mexico and Cuba. Everywhere, Humboldt measured, sketched and collected: temperature, magnetism, plants, rocks, languages, trade routes. His field notebooks turned the countryside into a living laboratory.

It was in these years that a key theme of any Alexander von Humboldt biography took shape: the insistence that no phenomenon made sense in isolation. In the Andean highlands he saw how vegetation changed with altitude much as it did with latitude in Europe. In tropical valleys he observed how deforestation shrank lakes and altered rainfall. In plantations he linked soil exhaustion and erosion to monoculture. These were not separate curiosities; they were pieces of a single pattern.

Inventing the geography of plants

Humboldt’s famous Essai sur la géographie des plantes (“Essay on the Geography of Plants”) distilled those observations into a new discipline. Instead of just classifying species, he mapped where they grew and why, overlaying altitude, temperature and humidity on a cross-section of the Andes to show plant communities stacked like bands on a mountain. The resulting “Naturgemälde” – literally a “painting of nature” – is often called a founding document of biogeography and a milestone for ecologists who study how climate shapes life.

Seeing climate change before the term existed

In the valley of Lake Valencia in what is now Venezuela, Humboldt noticed that cutting forests for plantations coincided with falling water levels. He argued that tree loss reduced shade, evaporation and moisture in the soil, making the local climate hotter and drier – a remarkably early description of human-induced climate change. Later he drew isothermal lines across maps of the world to compare climate zones, laying groundwork for the history of climatology and today’s global change science.

These insights, born from climbing volcanoes and watching rivers, are why many historians now describe Humboldt as a climate change pioneer and a central figure in environmental history – long before those terms existed.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Alexander von Humboldt

Personal Narrative: turning data into story

Back in Europe after 1804, Humboldt settled in Paris, then the nerve centre of scientific life. There he began turning boxes of specimens and notebooks into books. His Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent was not just a dry report; it blended atmospheric descriptions of tropical storms, volcanoes and forests with precise tables of measurements. Charles Darwin later carried this travelogue on the Beagle and said it shaped his own sense of what a scientific explorer could be.

Kosmos: a biography of the universe

In his seventies, Humboldt undertook his most audacious project: Kosmos, a multi-volume attempt to describe the physical universe as a unified whole. Based on public lectures in Berlin, Kosmos ranged from nebulae to mosses, from the history of astronomy to indigenous knowledge in the Americas. It tried to show that the same laws governed stars, storms and human societies, and that understanding the world scientifically could deepen, not diminish, our sense of wonder. The work cemented his reputation as a philosopher of nature and a key figure in Romantic science.

From volcanoes to magnetism: the polymath at work

Beyond books, Humboldt made technical contributions across disciplines. He studied volcano chains to argue they lined up over deep fissures in the Earth’s crust, helping shift geology away from the older “Neptunist” idea that rocks formed only from ancient oceans. He mapped variations in Earth’s magnetic field, documented the decrease of temperature with altitude, and quantified how ocean currents cool coasts, anticipating the concept of upwelling. Modern ecologists and geoscientists still cite him as a founder of ecological sciences between Linnaeus and Darwin, and as a key figure in the origins of global Earth system thinking.

Taken together, these works mean that any serious Alexander von Humboldt biography is also a history of early nineteenth-century science itself, from plant geography to geomagnetism.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

The craft of “Humboldtian science”

Humboldt was not a solitary genius sketching in a notebook; he was a master organiser of what later scholars call “Humboldtian science” – large-scale, comparative measurement of the natural world. He travelled with some fifty of the most advanced instruments of his day, from barometers and sextants to cyanometers that graded the blue of the sky. Back at his desk, he turned columns of numbers into comparative tables, graphs and maps, believing that visualisation could reveal patterns invisible in lists.

Networks of collaborators across continents

The Alexander von Humboldt biography is also the story of a man plugged into a vast correspondence network. He exchanged letters and specimens with botanists, astronomers and politicians from Mexico City to St. Petersburg. His closest field collaborator, Aimé Bonpland, collected plants and helped manage the day-to-day hardships of travel; later, in Paris and Berlin, printers, engravers and translators helped turn Humboldt’s findings into beautifully produced volumes. That collaborative infrastructure allowed him to integrate local knowledge – from Indigenous guides to colonial administrators – into a global picture.

Writing style: data wrapped in drama

Unlike many scientific pioneers, Humboldt wrote for a wide audience. His books mixed lyrical passages about fireflies over the Orinoco with discussions of atmospheric electricity. He believed that to persuade readers to care about nature, one had to make them feel it. That narrative flair explains why his works were devoured not only by scientists but also by poets, artists and statesmen – and why a modern Alexander von Humboldt biography must treat him as both data-driven observer and literary stylist.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Politics, empire and anti-slavery convictions

Humboldt travelled through colonial territories but was no simple celebrant of empire. In Cuba he denounced slavery and racial hierarchies, arguing in his political writings that nature’s diversity gave no support to ideas of racial inequality. Some critics thought he should have attacked colonial powers more directly, but his anti-slavery stance was clear in private letters and public works. He became a hero to figures in Latin American independence movements, even as he tried to maintain a scientist’s distance from partisan struggle.

Between Romantic prose and hard numbers

Later generations sometimes caricatured Humboldt as more of a Romantic writer than a rigorous scientist, especially as laboratory-based, specialised disciplines rose to prominence. Yet careful studies of his methods show that his lyrical sentences sat atop an enormous foundation of measurements and comparative tables. If anything, his challenge to today’s scientists is whether climate change and biodiversity loss can be communicated without some of that emotional range.

Why history forgot – and is rediscovering – him

One of the puzzles of the Alexander von Humboldt biography is how someone once hailed as second in fame only to Napoleon could slide into relative obscurity in the English-speaking world. Historians point to the rise of English-language science, anti-German sentiment after two world wars, and increasing specialisation that left little room for a generalist cosmographer. Recent scholarship and popular biographies have begun to reverse that forgetting, framing him as a missing link in the story of environmentalism and the history of climatology.

Impact on Science and on Wider Society

Inspiration for Darwin, Thoreau and beyond

Charles Darwin called Humboldt one of the greatest scientific travellers who ever lived. Reading Personal Narrative helped convince Darwin that a voyage could be a legitimate scientific project, not just an adventure. Henry David Thoreau’s nature writing and the emerging field of ecology borrowed Humboldt’s habit of tracing connections between forests, soil, water and human activity. Through such figures, the Alexander von Humboldt biography quietly shaped the development of evolutionary theory and environmental philosophy.

Shaping American ideas of nature

Humboldt never lived in the United States, but his 1804 visit and his books deeply influenced American art, literature and politics. An exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum has documented how his ideas about the sublime landscape, scientific exploration and environmental interconnectedness shaped painters of the American West, early conservation thinking and even debates about democracy and empire. This Smithsonian exhibition on Humboldt’s impact in America shows how a Prussian naturalist helped define the way a young republic saw its mountains and forests.

Reading the Alexander von Humboldt biography through modern climate science

In recent years, environmental historians and journalists have highlighted Humboldt as a “forgotten father of environmentalism” who recognised the dangers of human-driven climate change more than two centuries ago. A widely read Atlantic essay has argued that his view of nature as an interconnected web, and his warnings about deforestation and resource extraction, offer a powerful lens for thinking about today’s climate crisis. That Atlantic portrait of Humboldt as a pioneering environmental thinker captures how modern climate change pioneers still stand in his shadow.

Put simply, the reach of the Alexander von Humboldt biography extends from nineteenth-century botanical gardens and observatories to today’s debates over planetary boundaries and sustainability.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

A secular mystic of the natural world

Humboldt was not conventionally religious, but he wrote about nature with something close to spiritual intensity. In letters he described standing on mountain ridges and feeling that the Earth below and sky above formed a single, living organism. This blend of rational analysis and almost mystical awe helped him appeal both to scientifically minded readers and to those seeking meaning in the natural world – a balance that modern environmental communicators still struggle to achieve.

Friendships, loyalties and solitary habits

Personally, Humboldt could be both generous and exhausting. Friends recalled his rapid-fire conversations, darting from volcanoes to politics without pause. He cultivated intense friendships – with Bonpland, with the botanist Carl Sigismund Kunth, with politicians and artists – yet never married and often worked late into the night, hunched over maps and manuscripts. The Alexander von Humboldt biography is dotted with scenes of this solitary labour amid the bustle of Berlin salons.

A life lived in a Berlin apartment – and on the page

In his later decades, Humboldt lived in a modest apartment near the royal palace in Berlin, where visitors found piles of books, boxes of specimens and half-finished drafts of Kosmos. Courtiers, students and foreign dignitaries filed through, hoping for a conversation with the world-famous scientific explorer. The home became a kind of informal salon of Humboldtian science, where discussions of isothermal lines and the geography of plants flowed as easily as gossip about European politics.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Alexander von Humboldt

Russian expedition and the final data harvest

Remarkably, in his sixties Humboldt undertook another major journey, this time across the Russian Empire. Sponsored by the tsar, he travelled to the Urals and Central Asia, gathering data on geology and climate to compare with his Latin American observations. The expedition refreshed his comparative climate studies and fed directly into later volumes of Kosmos, underscoring how the Alexander von Humboldt biography is punctuated by bursts of fieldwork even in old age.

The struggle to finish Kosmos

Back in Berlin, Humboldt wrestled with the enormous task of finishing Kosmos. He complained in letters that he was drowning in material, yet he refused to simplify the project. The later volumes, some published posthumously from his notes, bear the marks of that struggle: digressive, encyclopaedic, but still driven by the desire to hold the world together in a single vision.

Death and global mourning

Humboldt died in Berlin in 1859 at the age of eighty-nine. Newspapers from New York to Melbourne reported his death; public ceremonies honoured him in cities across Europe, the Americas and Australia. Obituaries hailed him as a universal scholar, the greatest geographer of his time, and a founder of modern environmental thinking. It was a fitting end to a life spent trying to measure the Earth and, at the same time, to enlarge humanity’s sense of belonging within it.

The Lasting Legacy of the Alexander von Humboldt biography

Why his vision still matters

In the twenty-first century, the Alexander von Humboldt biography feels startlingly contemporary. His insistence that nature is a web of relationships – between climate, plants, animals, soils and human societies – aligns closely with the systems thinking of modern ecology and Earth system science. His warnings about deforestation and climate change resonate with current debates over carbon budgets and tipping points. His belief that science must be both quantitatively rigorous and emotionally compelling may be one of his most important lessons for our age.

To read a thoughtful Alexander von Humboldt biography today is to be reminded that our environmental crises are not just technical problems but failures of imagination. Humboldt offers a model of a scientist who was also a storyteller, a climate change pioneer who understood that seeing the planet as one interconnected whole could inspire both humility and action. Understanding his life and work does more than fill a gap in the history of science; it helps us see our own relationship with the Earth with sharper, more connected eyes.

Frequently Asked Questions about Alexander von Humboldt biography

Q1: Who was Alexander von Humboldt and why is he important?

Q2: How did the Alexander von Humboldt biography influence Charles Darwin?

Q3: In what way did Humboldt anticipate climate change science?

Q4: What is meant by “Humboldtian science”?

Q5: Why did Alexander von Humboldt become less well known over time?

Q6: What can modern readers learn from the Alexander von Humboldt biography today?