Few civilizations have left a legacy as luminous as that of ancient Greece. While their philosophers laid the groundwork for Western thought, their inventors and engineers built the very instruments that transformed ideas into action. The marvels of ancient Greek technology reveal a people who blended intellect with craft, reason with experimentation — and whose imagination still powers modern science.

From Myth to Mechanism: The Birth of Ancient Greek Technology

Long before modern machines, the Greeks were already bridging myth and mechanics. The same culture that dreamed of gods in chariots of fire also learned to harness wind, water, and motion. Far from being mere philosophers, the Greeks were master builders, astronomers, and innovators.

In the Mycenaean era, early engineers carved roads through mountains and built tunnels with geometric precision. The famous drainage project of Lake Copais — a vast network of channels and underground ducts — remains one of the earliest large-scale hydraulic feats known to humankind. It was not chance but Greek engineering that turned a swamp into fertile land.

Even in those early centuries, measurement, proportion, and mathematical logic guided every creation. This systematic approach would later define the classical world’s architecture and mechanics.

As noted in a New York Times feature on rediscovered inventions, historians are still uncovering evidence of Greek mechanical genius that predated Roman or even Renaissance breakthroughs.

A Civilization of Thinkers and Builders

By the 5th century BCE, innovation had become an inseparable part of daily life. Cities like Athens, Corinth, and Syracuse became living laboratories where geometry met practicality.

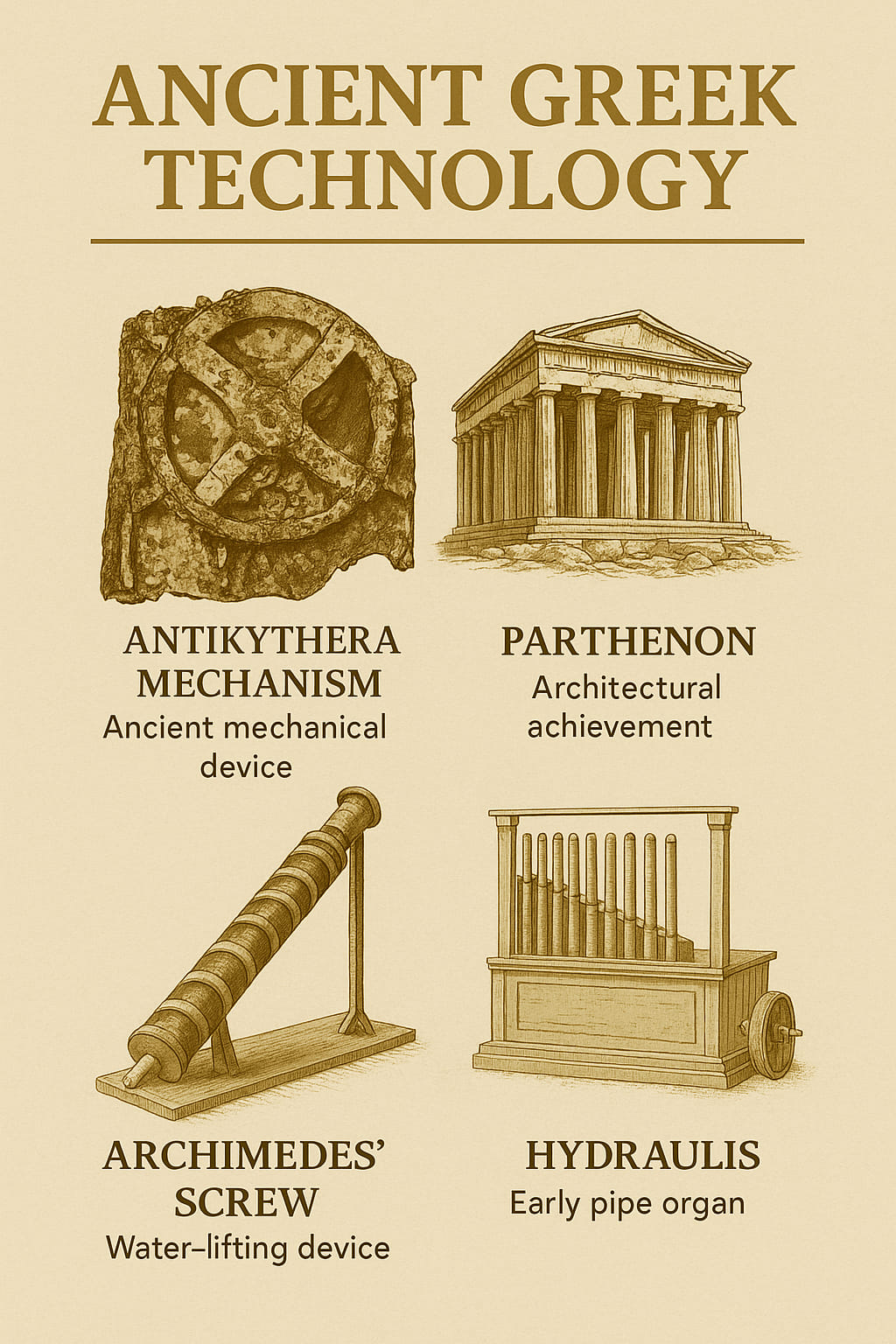

Greek architects designed temples that seemed effortless in symmetry yet required immense mathematical sophistication. The Parthenon’s subtle optical illusions — columns swelling at the middle, steps curving upward — are not decorative quirks but a reflection of ancient Greek technology applied to art and proportion.

Meanwhile, in the agora and the workshops, artisans and scholars collaborated. Potters used early forms of turntables; shipbuilders in Piraeus refined triremes that sliced through the Aegean like mechanical dolphins; and scientists such as Archytas and Ctesibius turned curiosity into invention.

The Golden Age of Greek Engineering

What made this civilization exceptional was its courage to experiment. The Greeks didn’t only observe nature — they imitated it. In Alexandria and Syracuse, thinkers constructed devices that echoed the movement of stars or the pressure of wind.

Archimedes, perhaps the most brilliant mind of all, formulated the laws of buoyancy and invented the “Archimedean screw,” a tool still used for irrigation today. Hero of Alexandria created the world’s first steam-powered mechanism, the aeolipile — a spinning sphere propelled by hot air jets, centuries before the industrial revolution. His automata — coin-operated fountains, self-opening temple doors, and even mechanical theaters — blurred the line between magic and mechanics.

These mechanical inventions were not curiosities but prototypes of future machines. The Antikythera mechanism, a sophisticated bronze device discovered in a shipwreck, could predict eclipses and planetary motions. Modern researchers call it the first analog computer — tangible proof of a technological mind millennia ahead of its time.

According to research published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology,, recent 3D reconstructions confirm the Antikythera mechanism’s complexity, suggesting that ancient engineers understood mechanical computation far earlier than once believed.

The City as Machine: Water, Fire, and Order

Urban life in Greece also reflected engineering genius. The Hippodamian grid, developed by the planner Hippodamus of Miletus, turned chaotic settlements into organized, navigable cities — the ancestor of modern urban planning.

Public water systems, pressurized fountains, and aqueducts turned cities into dynamic organisms. The tunnel of Eupalinos on Samos, carved simultaneously from both ends of a mountain, remains a triumph of geometric calculation. For the first time, technology was used to serve citizens rather than rulers — a hallmark of ancient Greek technology that separated it from other ancient powers.

Even entertainment bore traces of mechanical mastery. Amphitheaters were built with acoustic precision, ensuring that a whisper on stage could reach the furthest row. The hydraulis — a water-driven organ — filled arenas with music, a forerunner of the pipe organ that would dominate European cathedrals a thousand years later.

From Battlefield to Workshop: The Mechanics of Power

The same ingenuity that built temples also forged weapons. Greek warfare demanded mobility, precision, and discipline — traits reflected in their engineering.

The Macedonian phalanx employed the sarissa, a six-meter spear designed for strategic reach. Siege engines like the catapult, perfected by engineers under Dionysius of Syracuse, revolutionized combat. Yet, unlike later empires, the Greeks saw machines not only as instruments of war but as extensions of intellect — proof that thought could reshape matter.

This respect for design extended to maritime dominance. The trireme — a triple-decked galley of astonishing speed — embodied efficiency and elegance. Its oarsmen moved in perfect rhythm, turning human muscle into synchronized power. Each element, from hull shape to weight balance, reflected centuries of accumulated Greek engineering wisdom.

The Human Spark Behind the Mechanism

At the heart of every discovery lay the same impulse: curiosity. Whether it was Pythagoras exploring harmony through numbers or Theophrastus cataloguing plants, the Greeks sought patterns in chaos. They understood that knowledge without application was incomplete — that the universe could be measured, tested, and built upon.

This spirit still resonates. When we design a water turbine, a sundial, or a mechanical clock, we echo their legacy. Modern robotics, astronomy, and architecture trace intellectual lineage to their prototypes. The Greeks may not have had electricity, but they electrified thought itself.

Eternal Echoes of a Technological Soul

To speak of ancient Greek technology is to acknowledge a civilization that refused to separate art from science. Every device was a dialogue between beauty and necessity. From the polished marble of the Parthenon to the gears of the Antikythera mechanism, the message endures: perfection lies where precision meets imagination.

In the ruins of temples and fragments of bronze, we glimpse not the past, but the promise — a reminder that progress begins when we dare to ask, “How does the world work?” and “How can we build it better?”

Frequently Asked Questions About Ancient Greek Technology

What were the most important inventions of ancient Greek technology?

Greek engineering laid the foundation for mechanics, geometry, and hydraulics, influencing modern fields from civil engineering to robotics.

Because it teaches that invention is not just technical but philosophical — it begins with curiosity and ends with purpose.