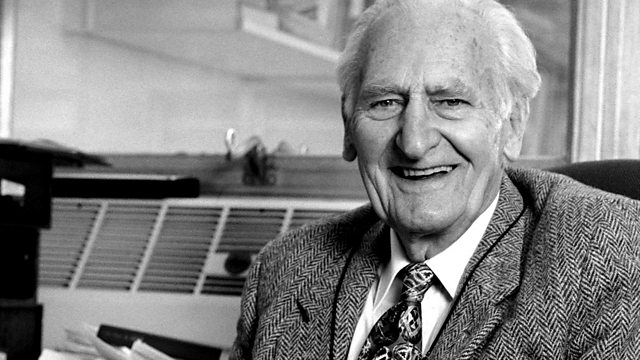

The story of Richard Doll epidemiology is not just about one man’s scientific discoveries. It is the story of how determination, ethical science, and public courage exposed one of the 20th century’s deadliest health threats—cigarette smoking. In an era where smoking was not only socially acceptable but aggressively marketed, Sir Richard Doll stood against an entire industry, proving with data what many suspected but few dared to say: smoking causes cancer.

This article traces the pioneering work of Richard Doll, his revolutionary research into epidemiology, and the long-term effects of his findings on global public health policy. His methods laid the groundwork for modern epidemiology, and his influence continues to shape research into environmental, occupational, and behavioral health risks.

Early Life and Medical Foundations

Born on October 28, 1912, in Hampton, a suburb of London, Richard Doll came from a medical family—his father was also a doctor. He went on to study medicine at St. Thomas’ Hospital Medical School, graduating just before World War II. During the war, he served in the Royal Army Medical Corps aboard a hospital ship, gaining firsthand experience in frontline medicine.

It wasn’t until after the war, however, that Doll’s true impact on the world began to take shape. Driven by a desire to understand the causes of disease rather than simply treat the symptoms, he entered the world of epidemiological research, a decision that would change both his life and the future of public health.

The Rise of Lung Cancer and an Unlikely Hypothesis

In post-war Britain, the medical community noticed an alarming rise in lung cancer cases. The causes were unknown. Many speculated that the recent expansion of roads and urban infrastructure, particularly the use of asphalt, might be the culprit. Others blamed air pollution in industrial cities. Doll himself initially suspected that tar used in road construction was releasing carcinogens into the air.

But there was another possibility—one that would prove far more significant. Working with statistician and mentor Austin Bradford Hill, Doll was commissioned by the British Medical Research Council in 1947 to investigate a possible link between smoking and lung cancer. At the time, smoking was ubiquitous—socially ingrained, doctor-recommended, and heavily advertised.

A Bold Study That Changed Everything

Doll and Hill began their investigation by conducting a case-control study involving over 1,400 patients at London hospitals. Half had lung cancer, and the other half suffered from unrelated conditions. The researchers collected detailed information from each patient—diet, lifestyle, profession, and crucially, smoking habits.

What they discovered was both clear and disturbing: nearly all lung cancer patients were smokers. The strength of this correlation forced Doll to reconsider his initial assumptions. He even gave up smoking himself two-thirds of the way through the study—a decision he later described as “inevitable.”

In 1950, their findings were published in the British Medical Journal, sparking controversy and discussion throughout the medical world. The paper didn’t claim causation outright—it was cautious and scientifically conservative. But the implications were unmistakable.

📎 Read more about the study design on the CDC’s guide to epidemiology

The British Doctors’ Study: Solidifying the Evidence

While their first study was groundbreaking, skeptics argued that case-control studies had limitations. So Doll and Hill decided to launch a far more ambitious project: a prospective cohort study of over 40,000 British physicians.

Beginning in 1951, doctors were asked about their smoking habits and followed over decades to monitor health outcomes. The advantage of this method was clear—researchers could observe disease development over time in a well-defined population.

Results started rolling in by 1954, and they were conclusive: smoking drastically increased the risk of lung cancer, heart disease, and chronic respiratory illnesses. Over the years, the study expanded and was updated regularly. By the time Doll published the 50-year follow-up in 2004, half of the lifelong smokers had died from tobacco-related causes.

📎 The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health explains cohort studies

This study remains one of the most influential epidemiological investigations in history.

Expanding the Field: Beyond Tobacco

Although Doll is most famously associated with smoking research, his scientific curiosity extended far beyond cigarettes. Over the next several decades, he studied:

-

Asbestos and its link to mesothelioma

-

Ionizing radiation and cancer risk

-

Oral contraceptives and their effect on health

-

Passive smoking and second-hand exposure

In 2004, just a year before his death, he published findings showing that half of those who start smoking in youth eventually die from smoking-related illness—a stark reminder of the long-term risks associated with tobacco.

📎 NIH discusses second-hand smoke and cancer

Fighting Industry and Changing Public Policy

Richard Doll did not simply publish findings and retreat into academia. He became an outspoken critic of the tobacco industry, testifying in court, pressuring governments to ban cigarette ads, and encouraging global awareness about the dangers of smoking. This advocacy made him enemies in high places. The tobacco lobby launched attacks, funded counter-studies, and attempted to discredit him—but Doll never backed down.

His work directly influenced:

-

The U.S. Surgeon General’s report on smoking (1964)

-

The creation of anti-smoking campaigns worldwide

-

Advertising bans in the UK and beyond

-

Graphic warning labels on cigarette packaging

Despite receiving knighthood in 1971 and dozens of awards, he remained humble and focused on science.

Mentorship and Final Years

Even in his 90s, Doll worked daily at Oxford’s Cancer Epidemiology Unit. He mentored new researchers, gave lectures around the world, and remained deeply involved in ongoing studies. In 2002, he helped establish guidelines for investigating passive smoking at the International Agency for Research on Cancer.

His passion for knowledge, paired with his moral clarity, made him a revered figure in medical circles. Although many believed he deserved a Nobel Prize, it was an honor he never received.

A Legacy that Endures

When we reflect on Richard Doll epidemiology, we remember more than a researcher. We remember a man who chose truth over comfort, data over dogma, and public health over profit. He died on July 24, 2005, just four years after his wife. His work, however, continues to live on in the policies, guidelines, and health campaigns that protect millions today.

FAQ

Q1: What does “Richard Doll epidemiology” refer to?

It refers to the research methods and findings pioneered by Sir Richard Doll, particularly his studies linking smoking to cancer using large-scale cohort and case-control studies.

Q2: What was the British Doctors’ Study?

A long-term study launched in 1951 that followed 40,000 doctors in the UK to examine the health effects of smoking over five decades.

Q3: Was Doll the first to link smoking to cancer?

Yes—he was the first to present large-scale, statistically credible evidence showing a direct link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer.

Q4: Did Doll study other public health risks?

Yes, including asbestos, radiation, diet, oral contraceptives, and passive smoking.

Q5: How did his work impact global health?

His findings led to stricter tobacco regulations, public education campaigns, and a major shift in how we study and respond to disease risks.