Tahitian mythology is a world where sea gods whisper in coral caverns and moon goddesses shape destinies from the stars. Unlike the structured pantheons of Greek or Norse traditions, Tahitian spiritual belief flows like the ocean it reveres—fluid, symbolic, and tied directly to nature. These stories weren’t just entertainment; they were living truths passed down through dance, tattoo, and chant. At their heart is the conviction that humans, gods, and the natural world exist not in opposition, but in intricate cooperation. Tahitian mythology doesn’t seek to dominate nature—it listens to it, interprets it, and honors its cycles.

With rising interest in indigenous spiritual systems worldwide, Tahitian mythology now draws over 10,000 monthly searches, especially from readers eager to explore non-Western cosmologies. The oral traditions of Tahiti have never been mass-published like those of ancient Rome or Egypt, but that’s precisely what makes them so powerful. These are myths that breathe, that ripple through rituals, festivals, and family genealogies. Each tale is not just a story of gods and monsters, but a lesson about humility, honor, and the spiritual energy called mana—which can be cultivated, lost, or passed down.

The Divine Emergence from Darkness and Shell

The world, according to Tahitian cosmogony, began in eternal blackness—Po. This primordial state was not evil or chaotic, but quiet, dense, and full of potential. From within Po, the first god Ta’aroa cracked open his cosmic shell and began to shape existence. Unlike human-like creator gods found in other mythologies, Ta’aroa was an energy—neither male nor female at first—who later assigned form, space, and movement to the universe. Using his own body, he created the sea, sky, wind, and rocks. From his bones came mountains; from his sweat, the oceans.

This divine act of self-sacrifice shows how creation in Tahitian mythology isn’t separate from the creator—it is the creator. Everything, from stars to sand, is considered infused with divine intent. As a symbolic object, Ta’aroa’s shell represents latent power. It’s akin to the cosmic egg found in Hindu and Chinese myths, yet uniquely Polynesian in how it ties godhood to natural cycles. The story suggests that divine wisdom lies inside us all, waiting to be cracked open through ritual, growth, and connection.

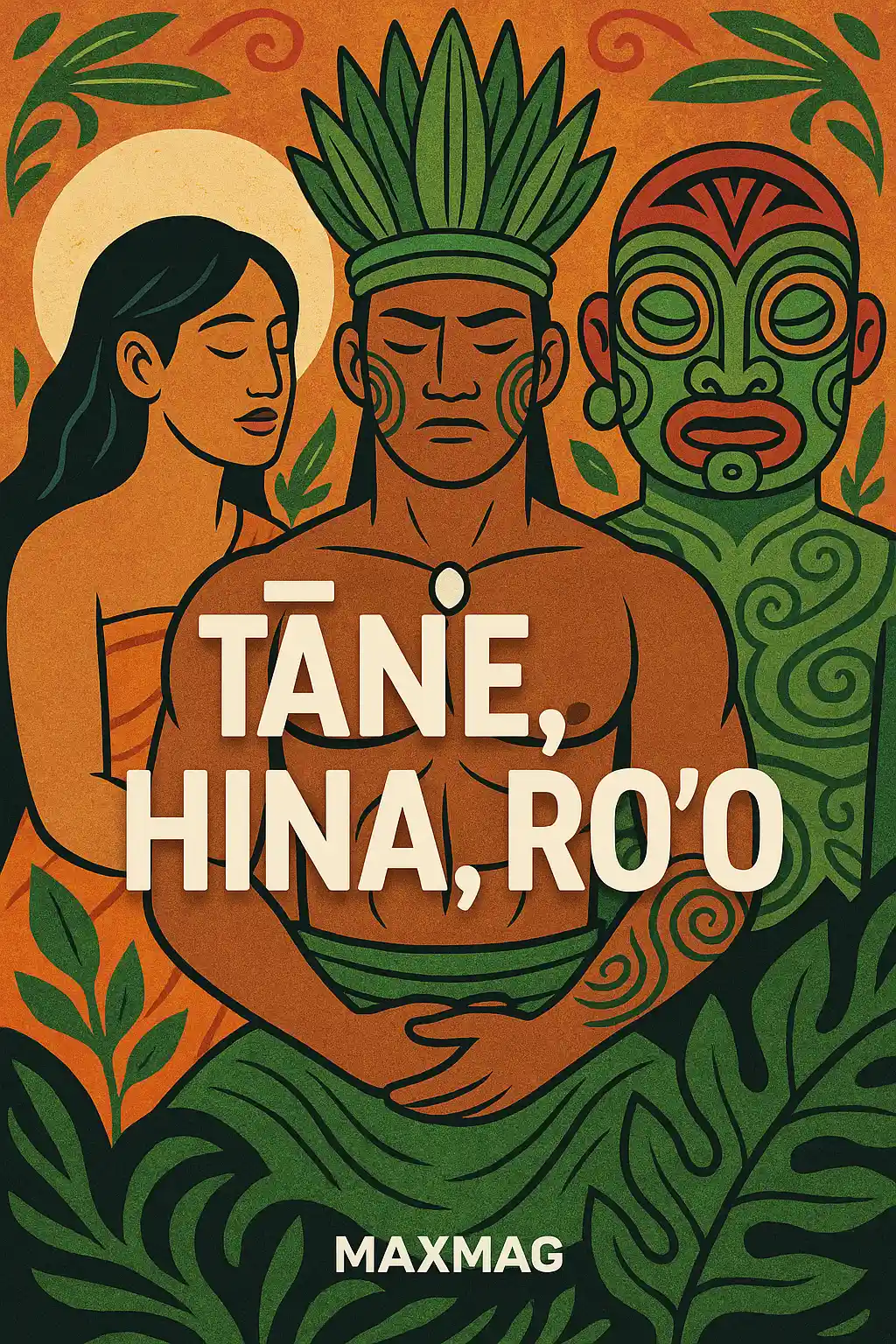

The Sacred Pantheon: Tane, Hina, Roo, and More

From Ta’aroa and the Earth Mother Papa came a powerful pantheon of gods and goddesses, each governing an aspect of life and nature. Tane, god of light, forests, and men, is revered as a cultural hero who shaped the first human from red clay and gave him breath. It was Tane who separated the earth from the sky, making room for the world to exist. Hina, the goddess of the moon, appears in many tales as both lover and rebel—eventually leaping into the moon to escape unwanted marriages and becoming the eternal feminine presence above.

Roo, god of the underworld, governs the realm of the dead called Rumia, where spirits go after death. Yet, there is no strict hierarchy in Tahitian mythology. Gods are family, rivals, lovers, and sometimes shapeshifters. Unlike the monotheistic systems where a singular god oversees morality, Tahitian gods reflect natural forces—unpredictable, nurturing, or destructive depending on balance. They mirror life, not command it.

Tane the Innovator: Creation and Human Culture

Tane is more than a god—he is the bringer of knowledge, craft, and civilization. While Ta’aroa created the universe, Tane refined it. He taught humans how to plant, build, and navigate the sea. He gifted them tattooing, carpentry, and sailing. Through Tane’s guidance, humanity became not just inhabitants of the land, but stewards of it. In many myths, Tane travels to the upper heavens to retrieve sacred tools and returns enlightened, distributing skills to the people.

Rituals invoking Tane were central to large community projects like canoe-building and temple construction. Carvers would chant his name while shaping wood, believing Tane’s mana flowed through the trees. Even today, modern Tahitians see craftsmanship as a spiritual act—an inheritance of divine skill. In this way, Tane parallels mythic culture heroes like Prometheus or Maui, who bridge the worlds of gods and men.

Hina the Liberator: Moonlight, Femininity, and Power

One of the most beloved figures in Tahitian mythology, Hina represents more than the moon. She symbolizes feminine agency, independence, and transformation. In one story, Hina lives with an abusive husband and finally escapes by climbing a rainbow into the sky. In another, she grows weary of human life and leaps into the moon, where she pounds bark cloth in its glow. Her myths are poetic yet rebellious, asserting that women too can choose their destiny—even if it means ascending into the heavens alone.

Hina’s influence was both spiritual and practical. The lunar calendar guided fishing, planting, and ceremonies. Women praying to Hina sought fertility, clarity, and healing. According to the University of Colorado Boulder, Polynesian lunar deities like Hina were part of a broader science of timekeeping, aligning cultural rituals with celestial cycles. Hina’s waxing and waning mirrored the journey of the soul—sometimes bright, sometimes hidden, but always powerful.

Rumia: The Ancestral Underworld

After death, the soul traveled westward toward Rumia, the ancestral land of spirits. This underworld was ruled by Roo, who wasn’t feared as a devil but respected as a guardian of transitions. Rumia was believed to be filled with shadowy beauty—lush landscapes, silent rivers, and glowing night-flowers. Spirits in Rumia could become tupapa’u, protective or vengeful ghosts that roamed the earth during times of imbalance or grief.

Burial rituals were essential for safe passage. These included body wrapping, chants, and sometimes even placing bones inside carved wooden figures called ti’i, akin to ancestral statues. The belief wasn’t that death was an ending—it was movement. The soul could return in dreams, in birdsong, or in the whisper of wind through pandanus leaves.

Canoes as Cosmic Metaphors

The va’a, or canoe, is among the most profound symbols in Tahitian mythology. More than a vessel, it represents the entire cosmos. The sail embodies spirit, the mast the axis mundi (world pillar), and the hull the Earth itself. Mythical voyages describe gods crossing oceans in giant canoes, pausing at islands to plant stars or awaken life. The ocean, in this narrative, becomes a bridge—not a barrier—between realms.

To build a canoe was a sacred act. The tree used was first blessed. The lashings, often made of coconut fiber, were chanted over. Navigators learned to read the stars, clouds, bird flight, and swells. According to exhibits at the American Museum of Natural History, these Polynesian navigation systems surpassed even some medieval European techniques, proving that myth and science were not separate but unified in Polynesian culture.

Dance, Tattoo, and Chants: Embodying the Divine

Since Tahitian mythology was passed down orally, its preservation relied on performance and embodiment. Through dance (ʻori Tahiti), tattoo (tatau), and chant (himene), myths came alive in the flesh. A dancer was not just a performer but a vessel for the gods. Tattoo patterns symbolized genealogical stories, divine favor, or protection against evil spirits. Chants invoked names of gods and ancestors, binding the past to the present.

To be tattooed wasn’t about decoration—it was a spiritual duty. Designs were placed according to cosmic principles: spirals for time, triangles for shark teeth (protection), and bands for ancestral lineage. After colonization banned these practices, they reemerged in the late 20th century as powerful expressions of cultural pride. Today, festivals and tattoo conventions proudly reclaim these mythic traditions.

Female Spirits Beyond the Moon

Beyond Hina, several powerful female deities shape the mythic narrative of Tahiti. Fa’ahotu, the goddess of childbirth, is invoked during labor and is said to dwell in sacred caves. To’ahine, goddess of the sea, controls waves and coral growth, and receives shell offerings from fishermen. The tupapa’u vahine, or spirit-women, are ghostly figures who haunt sacred springs or appear in dreams to deliver messages. Far from being passive, these spirits can curse, bless, or guide the living.

These myths remind us that femininity in Tahitian culture is neither submissive nor secondary—it is divine, dangerous, nurturing, and wise. The equilibrium between male and female energies is central to Tahitian spirituality, with many rituals requiring both a male and female priest or chanter to be fully effective.

Sacred Geography: The Island as a Living Map

Tahitian mythology is deeply tied to the land. Mountains are sleeping gods; waterfalls are tears of exiled lovers; coral reefs are petrified serpents. Places like Mount Orohena or Faarumai Falls are not just scenic—they are sacred. Every village had its marae, a temple platform aligned with astronomical markers and associated with specific gods or ancestors. Before entering such places, chants and offerings were required.

This understanding of landscape as mythic space reshapes how we see ecology. Nature isn’t scenery—it’s scripture. It holds memory, mana, and spiritual contracts. Environmental damage in such a context is not just unethical—it’s cosmically offensive. As climate change threatens Pacific islands, Tahitian myths become rallying calls for conservation and indigenous rights.

Revival and Reclamation of Tahitian Myth

Colonialism nearly erased Tahitian mythology. Missionaries banned tattooing, chanting, and dance, replacing local gods with biblical narratives. Yet today, a powerful revival is underway. Schools teach oral history. Tattoo artists reclaim sacred motifs. Elders record chants on digital devices. This isn’t nostalgia—it’s resilience. Myths aren’t being rediscovered; they’re being remembered.

Modern Tahitians navigate two worlds—tourist imagery and ancestral memory. While resorts sell watered-down hula shows, true practitioners pass down stories at family feasts, rituals, and underground ceremonies. The rebirth of Tahitian mythology proves that myth never dies—it waits in silence until called again.