Across the tapestry of global myth, few ideas carry such deep emotional and philosophical weight as the notion of the underworld. It isn’t just a place of death; it’s a space where cultural attitudes about life, morality, and the soul converge. These mysterious dimensions have been imagined in countless ways across civilizations—some terrifying, others serene. In this extended examination of mythological underworld realms, we journey through the Greek Hades, Norse Hel, and Egyptian Duat to uncover what they reveal about the human relationship with death.

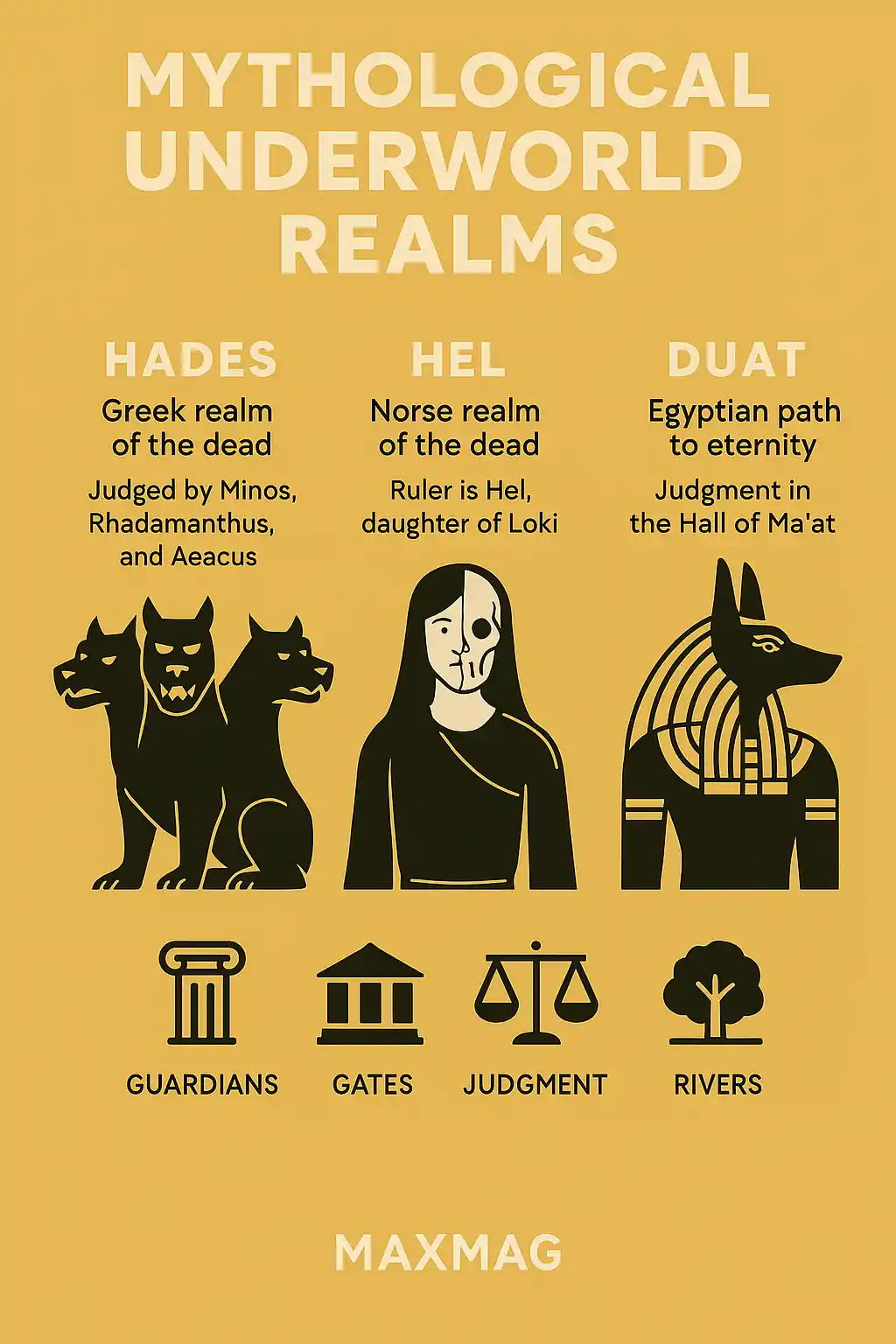

All three realms—though vastly different in atmosphere, structure, and purpose—share striking themes. From the role of judgment to the symbolism of rivers and guardians, they reflect our need to understand what happens after we die. Whether they offer punishment, peace, or purification, they mirror our deepest hopes and fears.

The Concept of the Underworld Across Mythologies

At its heart, the underworld serves as a metaphysical liminal space between the realm of the living and whatever comes next. While modern religions often present the afterlife as binary—heaven or hell—ancient cultures offered more intricate systems. Their mythological underworld realms were full of layers, guardians, trials, and transformations.

These realms are not simply “places.” They’re rich spiritual ecosystems where geography, morality, and cosmology intertwine. Souls didn’t just go to rest—they were judged, changed, or tested. The idea was not necessarily about reward or punishment but about cosmic balance.

Moreover, these underworlds are never random. They are structured, with rivers, gates, cities, and rulers, all contributing to their symbolic richness. They are, in many ways, reflections of the societies that created them.

Hades: The Shadowy Balance of Greek Belief

In ancient Greek thought, Hades is often misunderstood as a place of torment. But in reality, it’s a far more neutral and structured underworld. Named after its godly ruler, Hades is a realm where all souls—heroes and commoners, saints and villains—must travel after death.

Once the soul reaches the River Styx, Charon the ferryman transports it—provided the deceased was buried with an obol or coin. Those who were not properly buried wandered as ghosts, unable to find rest.

Upon arrival, the soul faces the triad of judges: Minos, Rhadamanthus, and Aeacus. These figures determine the soul’s destination:

-

Elysium: Reserved for heroes, poets, and the righteous—essentially the Greek version of paradise.

-

Asphodel Meadows: The middle ground, where average souls wander without suffering or joy.

-

Tartarus: A place of extreme punishment, not unlike the Christian hell, but reserved for oath-breakers, tyrants, and cosmic enemies like the Titans.

Interestingly, Hades also includes Lethe, the river of forgetfulness, where souls drink to forget their past lives before potential reincarnation. This idea of reincarnation influenced Greek philosophers like Pythagoras and Plato, whose concepts of the soul have echoed through centuries.

The mythological underworld realms in Greek culture reveal how the ancients viewed morality as deeply tied to remembrance, justice, and cosmic cycles—not just divine wrath.

To explore more about ancient beliefs in soul and rebirth, visit the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Classical Studies.

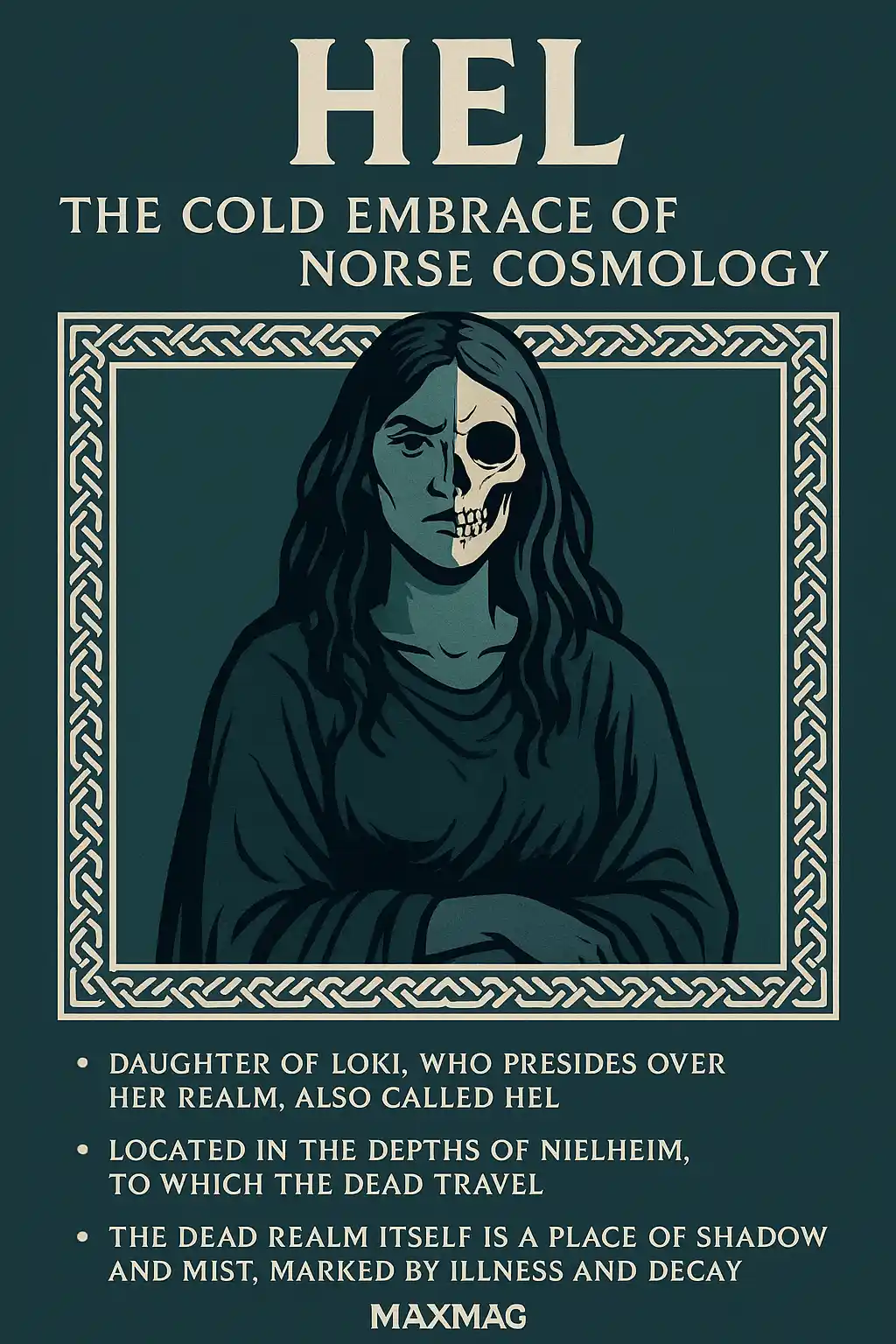

Hel: The Cold Embrace of Norse Cosmology

The Norse realm of the dead—Hel—offers a stark contrast to fiery hellscapes of later Christian imagination. Hel is a cold, misty domain beneath one of the roots of Yggdrasil, the World Tree. It is the final destination for those who die of disease, old age, or non-combat-related causes.

Hel, the goddess who rules this realm, is the daughter of Loki and the giantess Angrboda. Her appearance is dualistic—half of her face is beautiful and alive, the other half pale and corpse-like. This duality reflects the Norse ambivalence toward death: it is neither good nor evil, merely a natural end.

To reach Hel, the soul must cross the River Gjöll via the Gjallarbrú bridge, which is guarded by Móðguðr. The journey is long and perilous, echoing the belief that even after death, the soul must overcome trials.

Notably, Hel is not a place of punishment. It is simply the “other” destination from Valhalla or Fólkvangr, the realms reserved for warriors. In Norse mythology, mythological underworld realms like Hel carry no inherent shame—only a recognition that not everyone dies in battle.

Funeral rites, cremations, and ship burials were all part of the cultural preparation for the afterlife. The Vikings believed that memory was as valuable as gold, and Hel was a place where one might still be remembered by loved ones and gods.

Explore Viking burial customs and afterlife beliefs at The British Museum’s Norse Collections.

Duat: The Mysterious Egyptian Afterlife

Ancient Egyptian culture offered one of the most detailed and spiritually sophisticated visions of the underworld. The Duat was not merely a final resting place but a mystical passage—the terrain of gods, demons, and trials.

Each night, the sun god Ra would descend into the Duat aboard his solar barque, fighting off the serpent Apophis to ensure the rebirth of the sun each morning. This cyclical journey paralleled the soul’s own path after death.

The journey through the Duat was long and complex. The soul had to pass through twelve gates, recite magical spells (from the Book of the Dead), and face various guardian deities. The final judgment came in the Hall of Ma’at, where the heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of truth.

If the heart was heavier, it was consumed by Ammit. But if it balanced, the soul earned a place in the Field of Reeds—a paradise resembling an idealized version of Egypt.

Unlike other mythological underworld realms, Duat placed enormous value on personal ethics and knowledge. Even commoners were buried with scrolls, amulets, and maps to help navigate its perilous terrain.

This vision of the afterlife profoundly influenced later theological ideas, from the Christian judgment day to the Islamic concept of weighing deeds.

You can view authentic Book of the Dead artifacts through the Getty Museum’s digital archives.

The Architecture of Mythological Underworld Realms

What connects these seemingly unrelated realms—Hades, Hel, and Duat—is the structured nature of their cosmologies:

-

Geographic complexity: Each underworld is mapped with rivers, gates, palaces, and guardians. They’re not vague spiritual voids but architecturally defined domains.

-

Moral judgment: Whether via gods or balance scales, all souls are evaluated.

-

Symbolic guardians: Cerberus, Garm, and Ammit all serve as gatekeepers or punishers.

-

Cyclic rebirth: Especially in Egyptian and Greek myth, death is not the end but a doorway to another phase.

These traits suggest that mythological underworld realms were created not just to explain death but to give it purpose, order, and even hope.

The Modern Echoes of Mythological Underworld Realms

Today, the fascination with underworlds persists in storytelling, religion, psychology, and art. Modern authors like J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and Neil Gaiman draw inspiration from ancient myths to create new realms of the dead.

Carl Jung also tapped into underworld archetypes, proposing that journeys into darkness—literal or symbolic—are essential for psychological wholeness. This idea of “going below” as a rite of passage continues in modern therapy, film, and literature.

In many ways, these mythological underworld realms are mirrors—reflecting not only how cultures deal with death but also how they define life.

From Dante’s Inferno to Studio Ghibli’s “Spirited Away,” modern interpretations of the underworld show that these stories remain more relevant than ever.

For an academic dive into comparative mythology, see Joseph Campbell Foundation’s online resources.

Conclusion

Hades, Hel, and Duat each serve as cultural maps for what lies beyond the veil. They teach us that death is not just an end, but a profound continuation. In these mythological underworld realms, we find not only stories of punishment or paradise—but deep insight into how ancient people made sense of grief, justice, and the soul’s eternal journey.

They continue to fascinate us because they touch something eternal: our fear of death, our curiosity about what’s next, and our belief that some part of us might live on—in memory, in spirit, or in another world.