In the cradle of civilization—between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers—human beings first turned their gaze skyward and asked where they came from. To answer those questions, they created gods, wrote myths, and built temples. These earliest stories form what we now call Mesopotamian mythology—the world’s oldest recorded mythological tradition.

It wasn’t just about belief; these stories defined how people viewed nature, kingship, morality, and mortality. The gods lived in temples, walked the streets in statue form, and shaped everything from law to the afterlife. They weren’t abstract deities but real presences within society, consulted through ritual and represented through art, prayer, and public ceremony.

The Civilizations That Built the Myths

The foundation of Mesopotamian mythology was laid by the Sumerians around 3100 BCE, who wrote in cuneiform and worshiped deities like Enlil, Enki, and Inanna. Their city-states—Ur, Uruk, Eridu—were spiritual hubs where myth and statecraft were deeply interwoven.

As the Akkadians rose to power, they adapted these myths into their own language, preserving and enhancing the legends. These stories didn’t remain static—they evolved with the political needs and theological shifts of their time. New gods were introduced, old stories reinterpreted, and divine hierarchies reshaped.

Later, the Babylonians elevated their city god Marduk and composed the Enuma Elish, a creation epic that doubled as national theology. The Assyrians, with their military dominance, recast gods like Ashur into symbols of conquest, transforming earlier myths into instruments of empire. Mythology became a tool of power, reinforcing kingship as divinely ordained and conquest as cosmically justified.

The Structure of the Cosmos

Mesopotamians imagined the universe as three layers: heaven (Anu’s domain), earth (human territory), and the underworld (Kur), ruled by Ereshkigal. The sky was a dome of stone, and beneath the earth flowed Apsu, the sweet-water ocean. Mountains were considered the realm of gods and demons, while rivers—especially the Euphrates and Tigris—were seen as gifts from divine forces, requiring constant appeasement.

The stars were not just celestial bodies but scribes of fate. Priests charted constellations to read omens, predict floods, and guide decisions on war and agriculture. Astronomy and astrology merged into a sacred science, forming the early roots of empirical inquiry blended with myth.

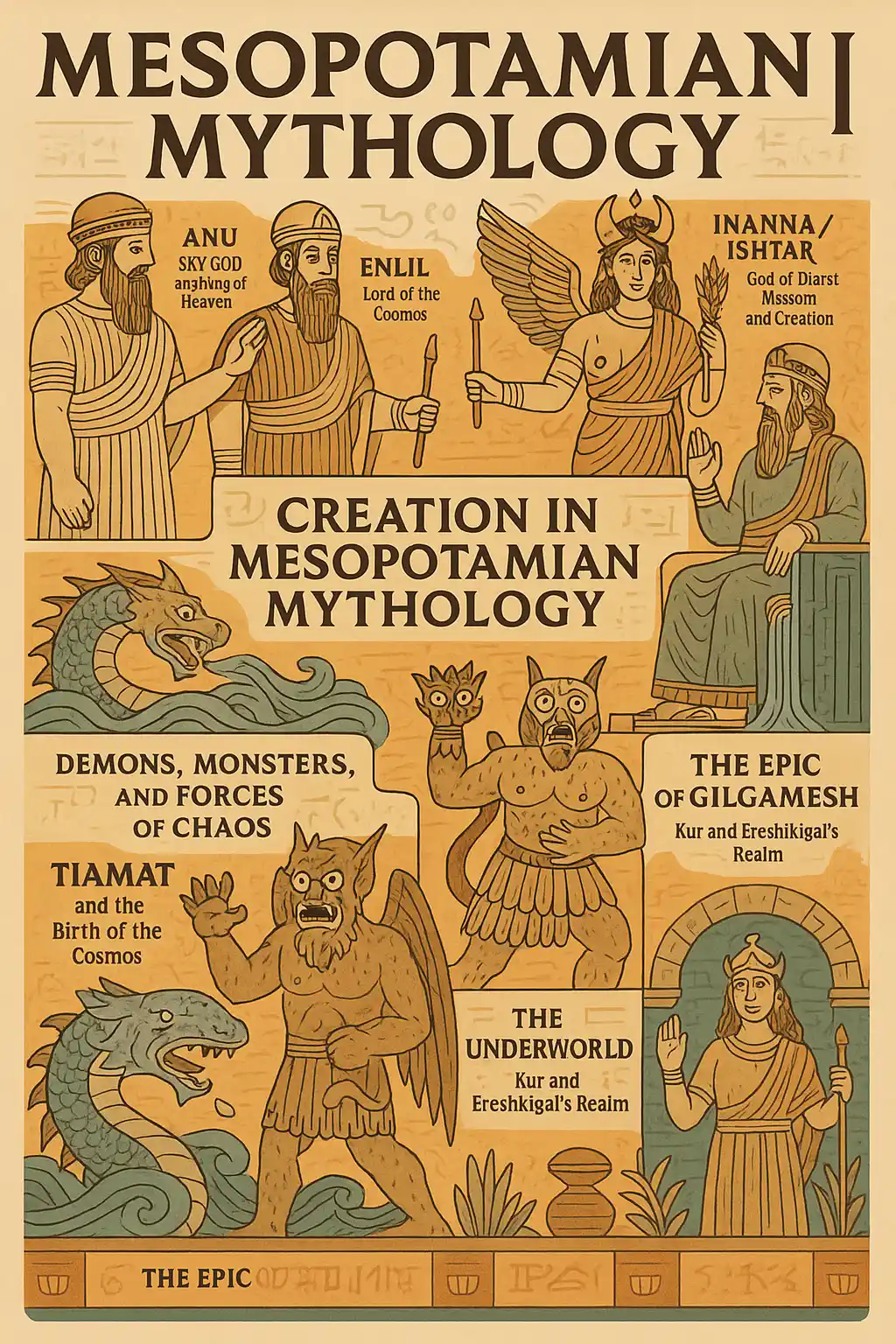

The Pantheon: Gods of Order and Chaos

The gods of Mesopotamian mythology formed a celestial court, not unlike a royal bureaucracy. At the head was Anu, the sky god, who bestowed kingship and divine favor. Enlil, his son, ruled the air, storms, and destiny, and was often the one to punish humanity for overstepping. Enki, god of freshwater and wisdom, acted as a trickster and protector of humankind, often working behind the scenes to balance justice and compassion.

Ishtar, or Inanna, stood at the heart of nearly every major myth. As a goddess of love, war, fertility, and political power, she embodied duality. She could seduce, destroy, bless, or curse. Her descent into the underworld—stripped of her power and reborn—became one of the oldest resurrection motifs in world mythology.

Other notable gods include Shamash, the sun god of justice, and Ninhursag, the earth mother and protector of birth and fertility.

The Creation of the World and of Mankind

The Enuma Elish, written on seven tablets, tells of a world born through cosmic struggle. After Apsu and Tiamat create the first gods, Apsu plans to destroy them for disrupting his rest. He is slain by Enki, prompting Tiamat to wage war against the younger gods. She births monsters and elevates Kingu, her consort, as her general.

Marduk, a young storm god, defeats Tiamat by trapping her in a net and splitting her body to form the heavens and the earth. With Kingu’s blood, he creates humans—not to rule, but to serve the gods. This myth is not only a creation story but also a justification for human subservience and ritual responsibility.

Daily Life Through Myth

Myths were not separate from daily life—they structured it. Farmers recited prayers before planting, artisans invoked gods of craftsmanship, and scribes trained in temple schools to copy sacred texts. Myths justified everything from tax collection to legal decisions. Even the practice of naming a child reflected the prevailing mythos; names often invoked a deity or wished divine favor.

Households had small altars. Amulets and protective charms featuring deities or demons were common. People lived with the constant awareness that the divine was not just above them—it was beside them, within their homes, and watching their behavior.

Magic, Divination, and Religious Power

Magic and religion were inseparable. Priests and exorcists read animal livers, threw bones, and interpreted dreams as divine messages. Diseases were seen as spiritual intrusions—curses, demonic possession, or divine displeasure. Healing involved both herbal remedies and ritual purification.

Demons were real forces. Lamashtu, for instance, threatened pregnant women, while Pazuzu—though a demon—could be summoned to protect against her. Protective spells, inscribed on tablets or figurines, were placed at doorways and bedsides. The supernatural world was vast, and humans had to navigate it carefully.

Gender, Power, and the Divine Feminine

The role of women in Mesopotamian mythology was multifaceted and powerful. Goddesses such as Ishtar, Ninhursag, and Nisaba (goddess of writing) held major religious roles. These figures weren’t merely consorts or mothers; they were creators, warriors, and enforcers of justice.

Inanna’s myths, in particular, contain some of the oldest reflections on gender duality, transformation, and agency. Her ability to descend into death and return alive positioned her as a bridge between the physical and spiritual worlds. Her symbols—lions, stars, and doves—speak to her wild paradox of ferocity and fertility.

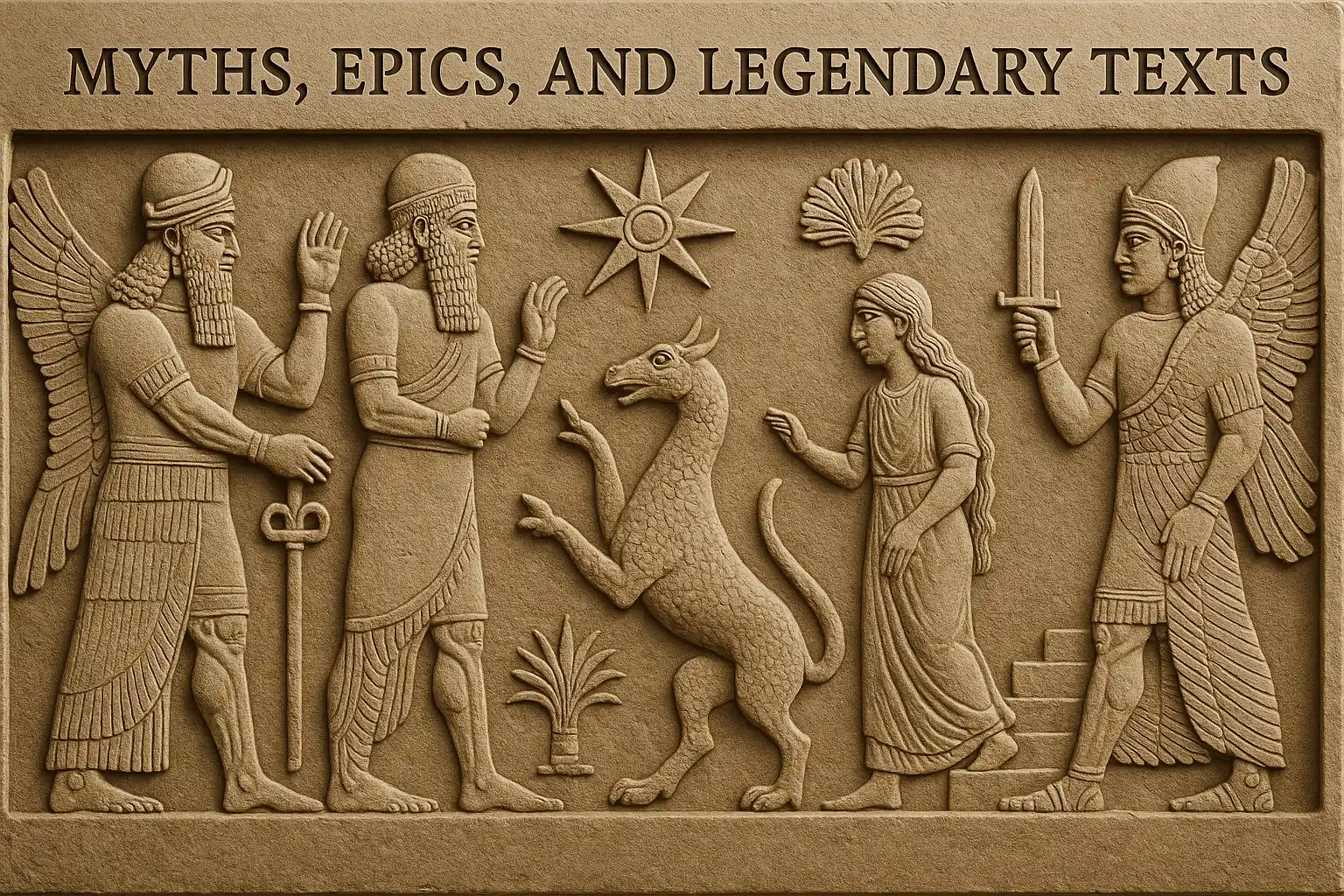

Myths in Art and Architecture

The gods and their stories were etched into every facet of ancient Mesopotamian life. Ziggurats—massive temple towers—symbolized mountains connecting heaven and earth. Relief carvings, cylinder seals, and statuary told visual stories of divine battles, godly unions, and mythical beasts.

Palaces and temples were inscribed with praises to the gods and mythic scenes meant to inspire awe and reverence. The Lamassu, guardian figures with wings and human faces, stood at palace gates to protect against chaos and invoke cosmic order. Through these depictions, mythology became a living part of the built environment.

Oral Tradition and Preservation

Before myths were etched in clay, they were sung, chanted, and passed from mouth to mouth. Professional storytellers, priests, and elders ensured the continuity of myth through ceremonies and public readings. The Epic of Gilgamesh itself likely began as a spoken tale long before it was committed to writing.

The invention of cuneiform transformed oral tradition into permanent memory. Clay tablets preserved myths that could be passed across kingdoms and centuries, allowing Akkadians and Babylonians to inherit Sumerian stories.

Comparative Myths: Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece

Many themes in Mesopotamian mythology reappear in Egyptian and Greek myth, though often with key differences. While Mesopotamian afterlife was bleak and silent, Egypt offered a path to judgment and renewal. Mesopotamian gods were capricious, while Greek gods often had more defined personalities and human flaws.

The idea of a hero’s journey—as seen in Gilgamesh—would echo in Hercules, Odysseus, and even modern narratives. Divine councils, trickster gods, resurrection myths, and the struggle between order and chaos are all motifs that began in Mesopotamia and echoed outward.

Modern Legacy and Influence

Elements of Mesopotamian mythology permeate modern faiths and literature. The idea of a great flood, found in the Epic of Gilgamesh, predates the biblical story of Noah. The structure of heaven and hell, the divine council, the rebellious god—these are all echoes of Mesopotamian thought.

Today, you can still explore these myths through museum archives like the British Museum or academic hubs such as the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago. Their digitized collections preserve the clay tablets and artifacts that once gave voice to the world’s first mythology.

Conclusion: Why These Stories Still Matter

The gods of Mesopotamia are long silent, their temples in ruin, their names half-remembered. But their stories remain. In a world of shifting belief and constant reinvention, Mesopotamian mythology endures as the first attempt to explain what it means to be human—flawed, mortal, curious, and yearning for meaning.

To understand these myths is to understand the birth of storytelling, religion, and civilization itself. They are not just relics of the past, but mirrors reflecting the roots of our shared humanity.