Japanese mythology is a rich tapestry woven with celestial beings, ancestral spirits, and mythical creatures that have shaped the spiritual identity of Japan for centuries. Unlike monotheistic traditions, Japanese mythology offers a universe brimming with divine presences known as kami—a term that encapsulates gods, spirits, and even natural phenomena. These myths explain the origins of the islands, human existence, natural disasters, and the social order, all deeply embedded in the Shinto and Buddhist traditions.

In this article, we’ll explore the main gods and goddesses of Japanese mythology, the most enduring legends, creation myths, and how these beliefs continue to shape Japanese culture today. Whether you are a myth enthusiast or someone curious about spiritual traditions, the world of Japanese mythology offers an unforgettable journey into the mystical.

The Origins of the Universe in Japanese Mythology

The creation of the universe in Japanese mythology begins with chaos. In the beginning, there was a shapeless void called Ame-no-Minakanushi, the first kami to emerge. Following him, the cosmic balance unfolded with the appearance of two key deities: Izanagi and Izanami, the divine couple who were given the heavenly spear and tasked with creating the land.

From their union came the Japanese islands, known as the kuniumi, followed by the birth of numerous other gods (kamiumi). However, tragedy struck when Izanami died giving birth to the fire god Kagutsuchi. Overcome with grief, Izanagi ventured into Yomi, the land of the dead, to retrieve her. The myth mirrors themes in other cultures, such as the descent of Orpheus into Hades, but carries its own unique Shinto flavor. Izanagi’s purification after fleeing from Yomi led to the birth of three powerful deities: Amaterasu (sun goddess), Tsukuyomi (moon god), and Susanoo (storm god).

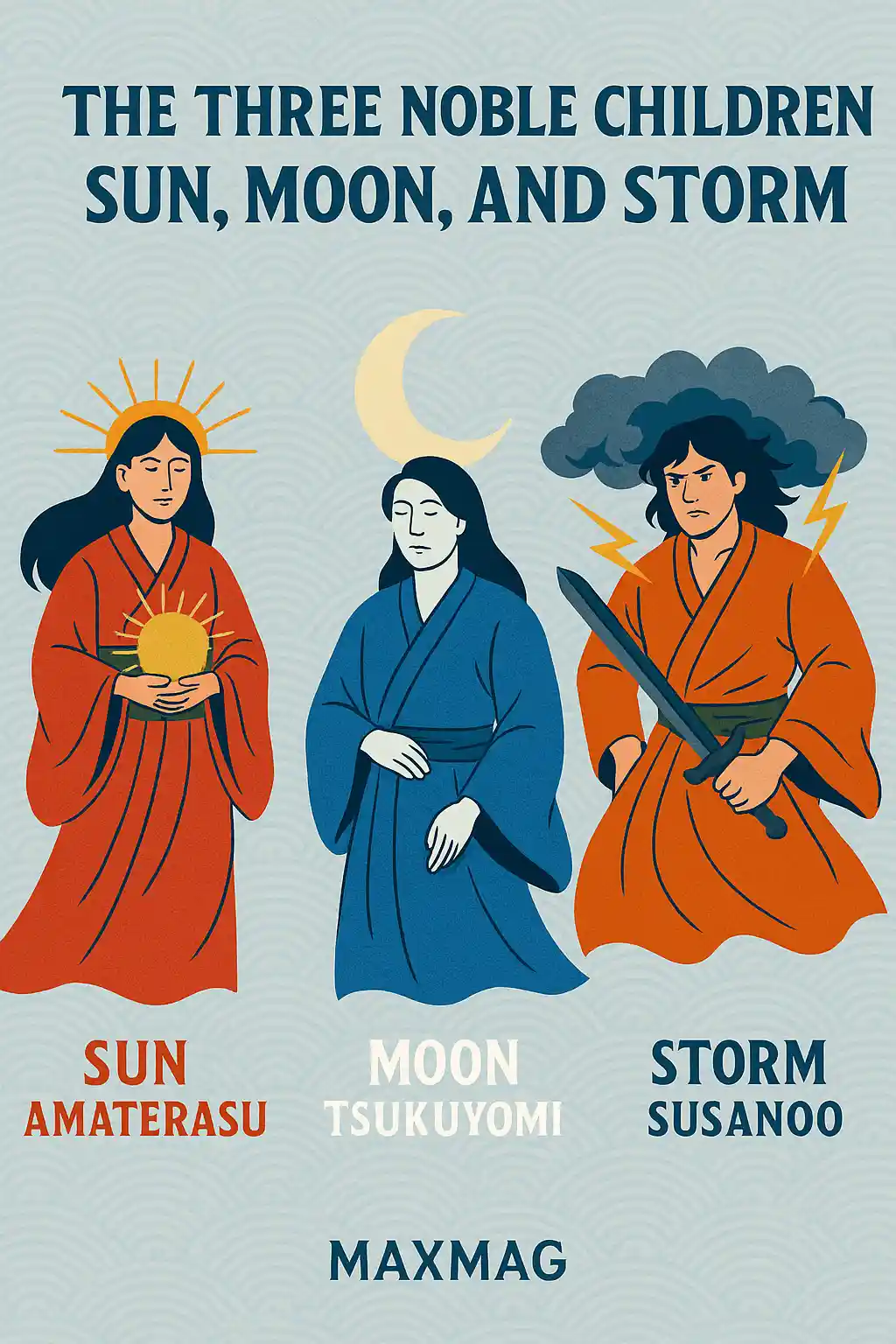

The Three Noble Children: Sun, Moon, and Storm

These three children of Izanagi represent fundamental forces of nature in Japanese cosmology:

-

Amaterasu, the sun goddess, is perhaps the most revered deity in Japan. The Imperial Family claims descent from her, which has helped legitimize their divine right to rule. Her story is crucial in understanding Japanese state religion.

-

Tsukuyomi, the moon god, is a lesser-known but significant figure who is often estranged from his sister due to acts of violence.

-

Susanoo, the chaotic storm god, is a central figure in various myths, such as the slaying of the eight-headed serpent Yamata-no-Orochi.

This triad continues to influence Shinto shrines and festivals. The Ise Grand Shrine, dedicated to Amaterasu, is one of the most sacred sites in Japan and a popular destination for pilgrims and tourists alike.

Kami: Spirits in All Things

Unlike Western mythology, Japanese mythology does not distinguish sharply between gods, spirits, and natural elements. Instead, the term kami covers a wide range of spiritual entities: from deities to ancestors to natural features like mountains, rivers, and wind. This reflects Shinto’s animistic roots, where every element of nature has its own spirit.

For example:

-

Mount Fuji is considered a sacred being.

-

Trees, particularly old ones, are often marked with shimenawa ropes to indicate the presence of a kami.

-

Even objects like swords, mirrors, and jewels—when imbued with history or ritual significance—can possess spiritual power.

This concept aligns closely with indigenous spiritual systems around the world. For those interested in comparative mythology, Slavic Mythology offers a similar reverence for nature spirits and deified natural phenomena. Read more about Slavic Mythology.

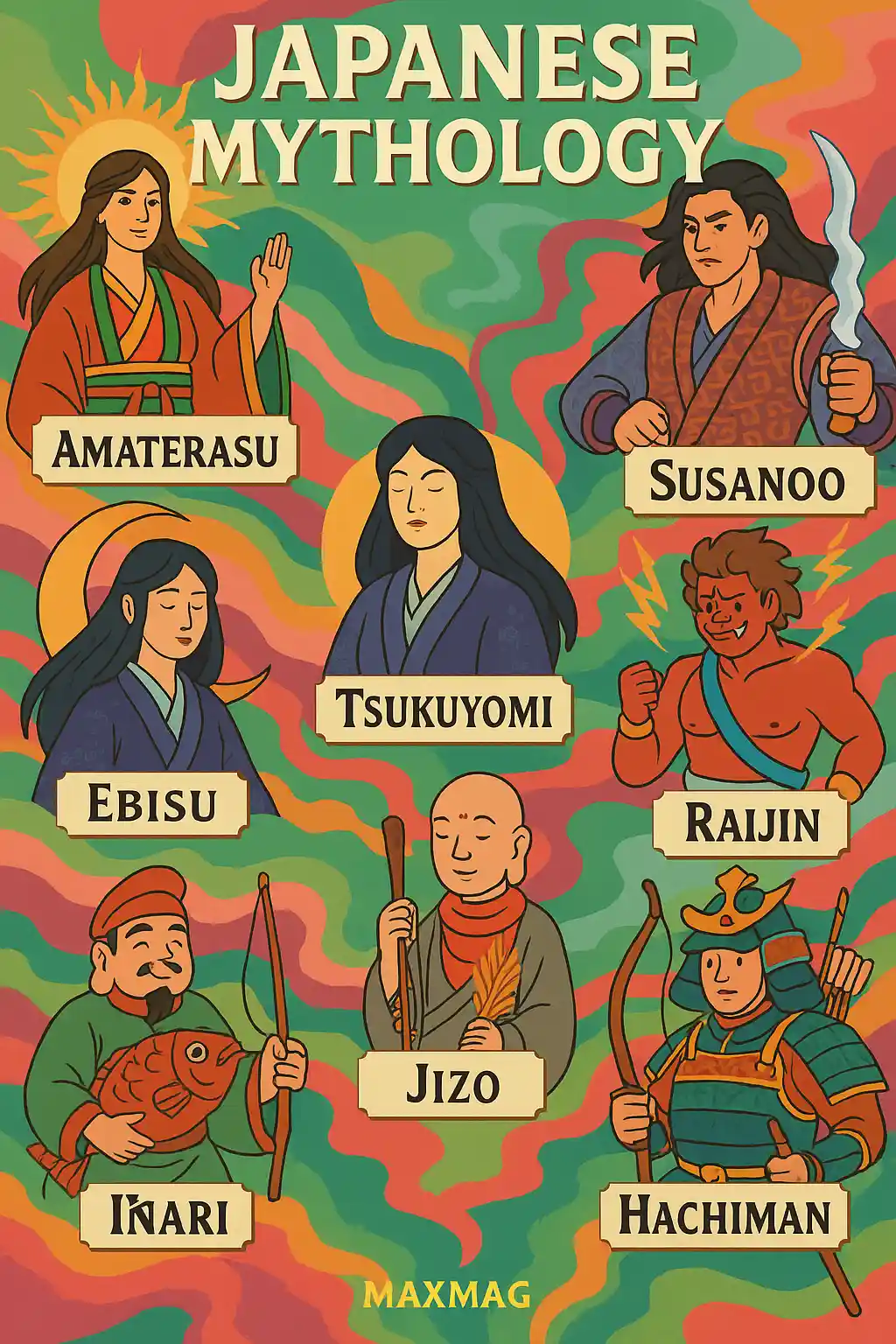

Key Deities and Legendary Figures

Here are some of the central figures of Japanese mythology:

1. Amaterasu

The sun goddess, whose myth involves hiding in a cave after a feud with her brother Susanoo, thus plunging the world into darkness. The gods eventually coaxed her out using a mirror and a celebratory dance—a myth still reenacted in Shinto rituals today.

2. Susanoo

Famous for his chaotic nature and eventual redemption through heroic acts like defeating Yamata-no-Orochi. His myth has similarities to dragon-slaying legends in European cultures.

3. Tsukuyomi

Though less emphasized, he embodies the mystical and distant qualities of the moon and is often seen as aloof and severe.

4. Inari

The kami of rice, agriculture, and prosperity. Often associated with foxes (kitsune) that serve as messengers, Inari is one of the most worshipped deities in Japan.

5. Hachiman

The god of war and protector of Japan, particularly revered by the samurai class.

6. Tenjin

A deified scholar and poet, Tenjin is worshipped as the god of learning and is often prayed to by students before exams.

Yokai: The Shape-Shifting Spirits and Monsters

One cannot speak of Japanese mythology without mentioning the yokai, supernatural creatures that include demons, goblins, ghosts, and shape-shifting animals. These beings often reflect cultural anxieties, natural disasters, and moral lessons.

-

Kappa – Water creatures that drag people into rivers unless appeased.

-

Tengu – Bird-like warriors who are both protectors and tricksters.

-

Kitsune – Fox spirits with magical powers and the ability to take human form.

-

Yuki-onna – The snow woman who appears during blizzards and lures travelers to their deaths.

The concept of yokai has been deeply influential in Japanese literature, manga, and even horror films. The Smithsonian Institution has extensively documented yokai in art and folklore, highlighting their relevance in Japan’s visual culture.

Shinto Rituals and Modern Practice

While Buddhism is a prominent religion in Japan, Shinto remains integral to cultural identity. Shinto rituals often involve:

-

Purification with water or salt.

-

Offerings of food, sake, or flowers to kami.

-

Festivals (matsuri) celebrating seasonal changes or historical events.

Shrines across Japan host yearly festivals that blend ancient myth with community celebration. These include dramatic reenactments of myths, such as the Ama-no-Iwato dance to lure out Amaterasu, or ritual prayers for bountiful harvests addressed to Inari.

Today, many Japanese people visit shrines on New Year’s Day (Hatsumode) or before significant life events—not necessarily as religious acts, but as cultural traditions rooted in Japanese mythology.

Buddhist Influences and Syncretism

From the 6th century onward, Buddhism began to intertwine with native Shinto beliefs. Rather than replacing the Shinto pantheon, Buddhist doctrines were adapted. Kami were sometimes seen as manifestations of Buddhist deities (a concept known as honji suijaku).

One striking example is the merging of the sun goddess Amaterasu with the bodhisattva Dainichi Nyorai in esoteric Buddhism. This syncretism blurred lines between the two traditions, enriching the mythological canon and temple iconography.

The American Museum of Natural History hosts exhibitions on Buddhism and Shinto syncretism, shedding light on how spiritual traditions evolve over time.

Japanese Mythology in Contemporary Culture

Myths never die—they evolve. Japanese mythology remains alive through:

-

Anime and manga, such as Naruto, Spirited Away, and Inuyasha, all of which feature kami, yokai, or legendary narratives.

-

Literature and poetry, especially in haiku and classic epics like The Tale of the Heike.

-

Video games, such as Okami, which retells the story of Amaterasu in the form of a white wolf.

Moreover, shrines like Fushimi Inari and Meiji Jingu are not only religious centers but also major tourist destinations. These sites allow visitors to witness living traditions rooted in Japanese mythology.

Two Additional Paragraphs (New)

Mythology as a Guide for Ethical Behavior

Beyond religious practice, many myths in Japanese folklore serve as ethical parables. Stories about yokai punishing greed, laziness, or disrespect for nature are often used to instill moral lessons in children. The tale of Urashima Taro, for instance, warns against ignoring the passage of time and the value of living in the present. In this way, mythology functions as a spiritual compass for social conduct.

The Preservation of Oral and Regional Traditions

Although popular myths are documented in ancient texts like the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, countless regional variations and oral stories still survive. These local legends are passed down through generations during village festivals, puppet plays, or storytelling by elders. They add texture to Japan’s mythological heritage, ensuring that the spirit of Japanese mythology remains dynamic and diverse across prefectures and islands.