Hawaiian mythology is a vibrant tapestry of gods, spirits, and forces of nature passed down through generations of Polynesian voyagers and island-born descendants. Unlike Western mythologies stored in dusty volumes or museums, Hawaiian myths are alive—in the lava flowing from Kilauea, in the chants of the elders, and in every towering cliff or sacred grove preserved across the islands.

The Hawaiian Islands are one of the most isolated landmasses on Earth, and yet their mythology connects them to a vast oceanic family of cultures through shared roots in Polynesian cosmology. Still, Hawaii’s stories are deeply unique. With fiery goddesses, shape-shifting demigods, and living landscapes, Hawaiian mythology isn’t a distant past—it’s an active part of identity, spirituality, and everyday life in the islands today.

Origins of Hawaiian Mythology

Hawaiian mythology began long before the islands themselves were fully formed. As early as 500 AD, Polynesians from the Marquesas and Tahiti began arriving in Hawaii using celestial navigation. Alongside tools, crops, and domesticated animals, they brought their oral traditions—gods, chants, legends, and creation stories. These would eventually evolve into something distinctly Hawaiian.

Unlike modern religious texts, Hawaiian mythology was not written until Western contact centuries later. Knowledge was passed down by oral historians, genealogists, and hula practitioners, each trained to memorize long chants and complex family trees. Hawaiian cosmology does not separate the sacred from the natural—the two are one and the same. Mountains, trees, rivers, and lava are not scenery but embodiments of divine forces. Nature itself breathes, listens, and remembers.

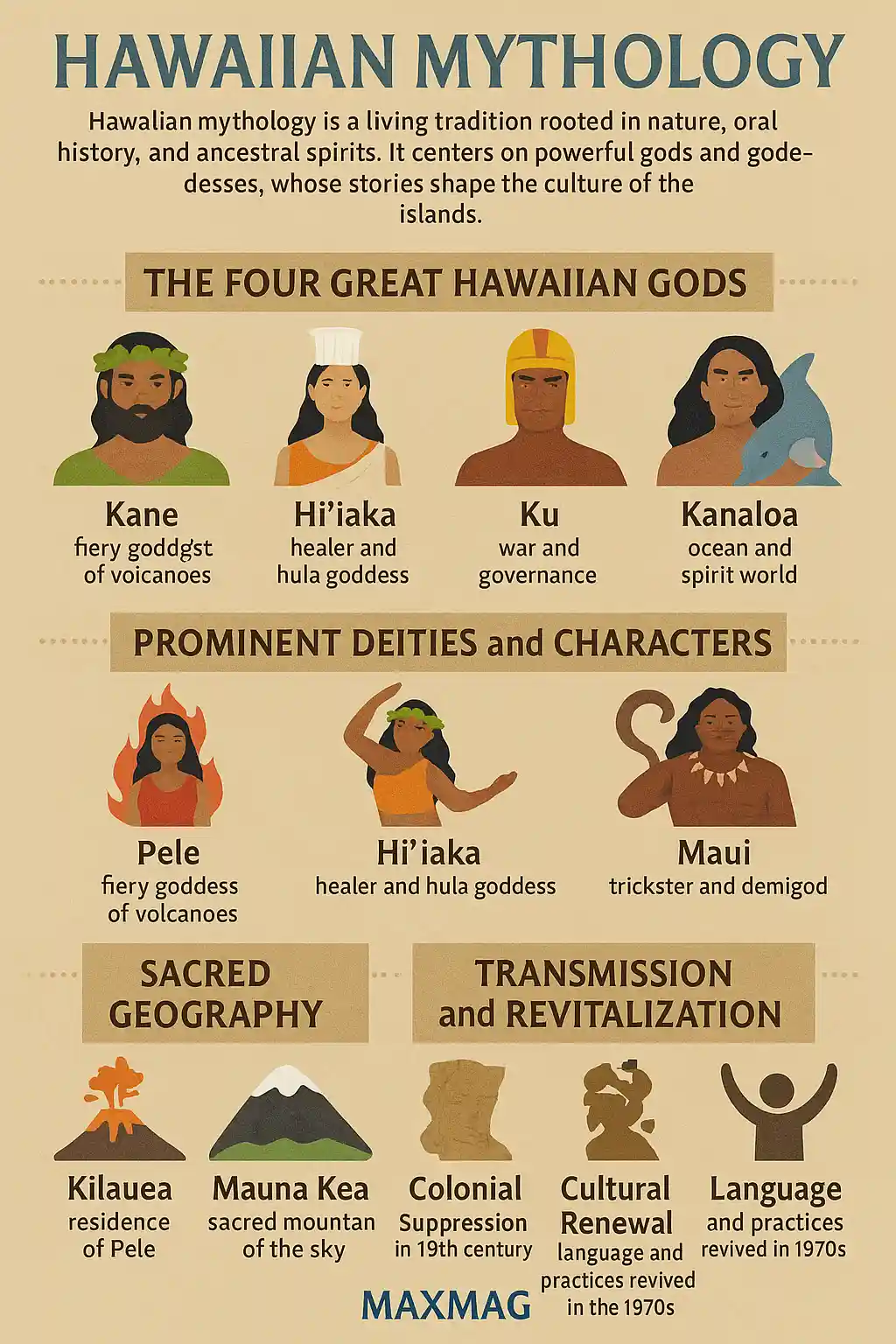

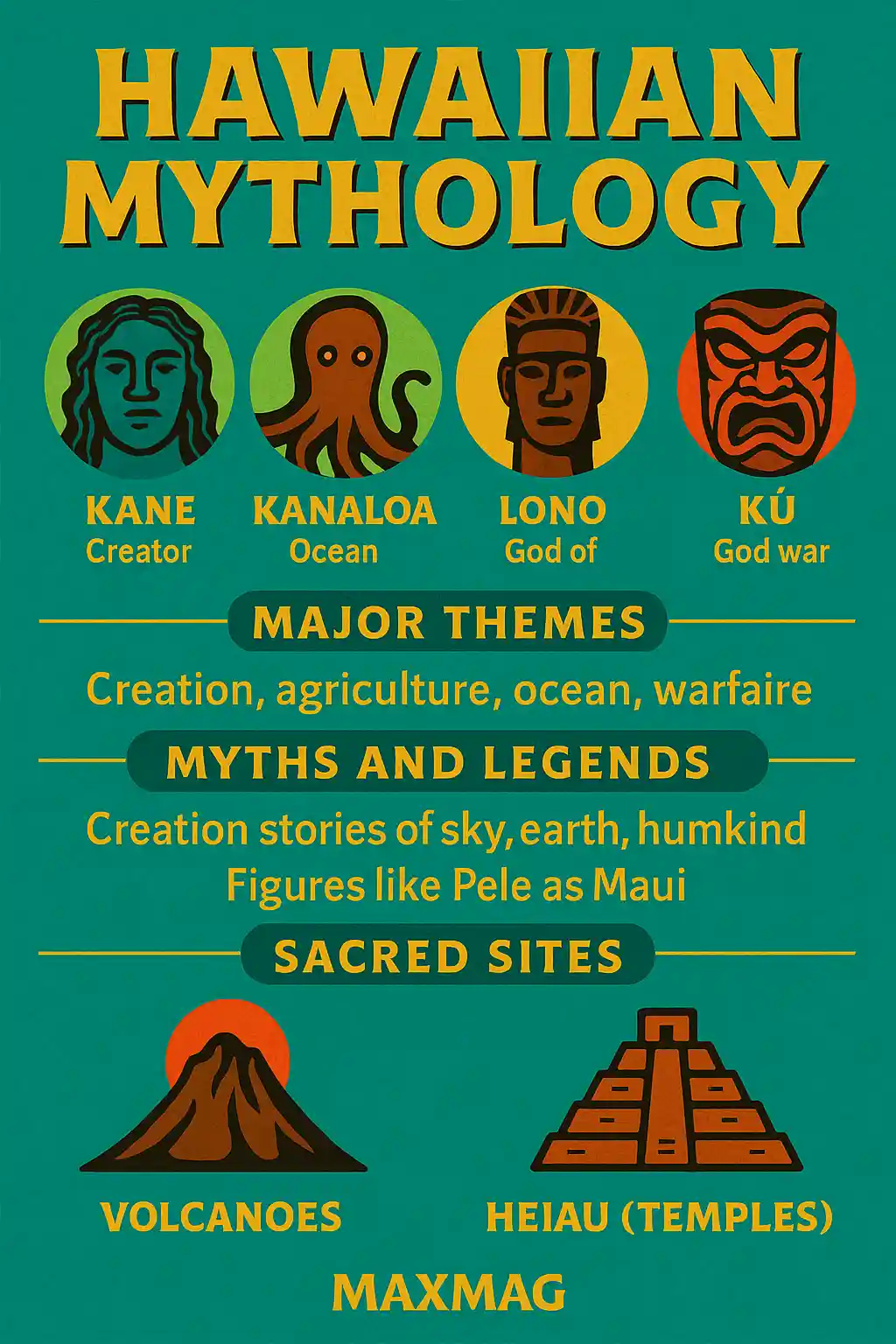

The Four Great Hawaiian Gods

At the heart of Hawaiian spirituality are four great gods—Kāne, Lono, Kū, and Kanaloa—each representing major natural forces and societal roles. They were worshipped by all classes of society and honored in temples known as heiau.

Kāne: The Creator of Life and Light

Kāne is often described as the chief god and source of all living things. He is associated with light, forests, freshwater, and creation. In some chants, Kāne was said to have formed the first human from red earth and animated him with divine breath.

Unlike Kū or Kanaloa, Kāne was not worshipped through human sacrifice. Instead, he was honored through offerings of water, fruit, flowers, and prayer. Freshwater springs called wai kāne (waters of Kāne) were revered as his gift to the world.

Lono: Peace, Agriculture, and Renewal

Lono governs rain, clouds, agriculture, and fertility. He is most famously associated with the Makahiki festival—a season of peace and prosperity lasting several months. During Makahiki, warfare was forbidden, taxes were collected, and communities celebrated with feasts, games, and ceremonies in his honor.

Lono’s arrival on earth is dramatized during the festival by parading carved images wrapped in white kapa cloth, carried along the coast to bless the land. When Captain Cook arrived during the Makahiki in 1778, some Hawaiians believed he might be Lono incarnate—a fatal misunderstanding that ended in violence.

Kū: The God of War and Political Power

Kū represents strength, leadership, war, and fishing. He was the only major god to receive human sacrifice, especially in luakini heiau (war temples). Chiefs often aligned themselves with Kū, invoking his favor before battles or conquests.

Yet Kū was not solely a violent figure. He was also the god of labor, particularly fishing and farming. His multifaceted personality reflects the complexity of Hawaiian society—where might and productivity went hand in hand.

Kanaloa: Oceanic Depths and Spiritual Balance

Kanaloa is sometimes considered a twin or counterpart to Kāne. He rules over the ocean, underworld, and realms of spirit and death. Navigators and healers often prayed to Kanaloa for protection during deep-sea voyages or spiritual rituals.

In myths, Kanaloa is also a challenger of authority, probing the boundaries between life and death, land and sea, sacred and profane. Dolphins, whales, and other sea creatures are said to be manifestations of his spirit.

Other Deities and Mythic Figures

While the four major gods formed the core of ancient worship, countless other deities and supernatural beings fill the stories of Hawaiian mythology.

Pele: Goddess of Fire and Volcanoes

Pele is one of the most iconic Hawaiian deities. She rules over lava, fire, lightning, and transformation. Residing in Halemaʻumaʻu crater at the summit of Kilauea volcano, Pele is revered not only for her destructive power but for her creative force. Each eruption is seen not just as disaster but renewal—the birth of new land.

In one myth, Pele traveled from Tahiti with her siblings, fleeing her jealous sister Namakaokahaʻi, a goddess of the sea. As Pele journeyed across the islands, she created volcanoes to make a new home. Ultimately, she found refuge in Kilauea, where her spirit still lives.

Locals often report sightings of a mysterious woman in red near eruption sites. Taking lava rocks from her domain is considered disrespectful—and many return them by mail after suffering misfortune.

Hiʻiaka: The Healer and Heroine

Hiʻiaka is Pele’s youngest sister and a powerful goddess of healing, forest life, and hula. Her most famous myth describes her perilous journey to retrieve Pele’s lover from Kauai. Along the way, she fights monsters, communicates with spirits, and spreads new forms of chant and dance.

Hiʻiaka represents balance, compassion, and loyalty. She is deeply honored by hula practitioners and forest conservationists alike. Ancient groves where she was said to rest are still preserved today.

Māui: The Trickster and Cultural Hero

Māui is perhaps the most popular demigod in Hawaiian and Polynesian mythology. He is clever, brave, and known for reshaping the world through bold acts. In Hawaiian stories, Māui slows the sun to give people longer days, lifts the sky to make room for trees, and fishes the islands up from the sea.

While playful and sometimes arrogant, Māui always uses his powers to help humankind. His tales blend humor with deep lessons about persistence, intellect, and risk.

Kamapuaʻa: The Pig Demigod and Lover of Pele

Kamapuaʻa is a shapeshifter who can transform between a wild pig and a handsome man. He is linked with water, agriculture, and the growth of forests. His stormy love affair with Pele—fire clashing with rain—is legendary. While their relationship is turbulent, their union symbolizes the elemental balance of the islands.

Kamapuaʻa is both revered and feared. He protects fertile lands but also plays tricks on mortals. Many valleys, waterfalls, and groves across Oʻahu and Maui are associated with his name.

Sacred Geography: Myth Written in the Land

One of the most profound aspects of Hawaiian mythology is its deep integration with the environment. Sacred geography is not metaphorical—it is literal. Mountains, rivers, lava flows, petroglyph fields, and even individual trees are considered the physical evidence of divine presence.

For instance, the Nā Pali cliffs are believed to be the home of ancestral spirits. The island of Molokaʻi is known for its powerful kahuna (priests). Kilauea is not just a volcano—it is Pele herself.

When developers seek to build on sacred mountains like Mauna Kea, many Hawaiians object not on environmental but on spiritual grounds. To disturb such places is to disrespect the gods and ancestors who dwell there.

The American Museum of Natural History and Smithsonian Institution have documented how sacred sites in Hawaii are inseparable from the culture’s oral tradition and belief systems. Unlike secular land use models, Hawaiian cosmology views place as personified.

Chants, Oral Traditions, and Lineage

Hawaiian mythology has survived centuries thanks to oral tradition. Chants (oli), songs (mele), and storytelling (moʻolelo) have preserved the genealogies of gods and humans alike. These were memorized by trained specialists, often attached to royal courts or religious orders.

Genealogies (moʻokūʻauhau) serve not only to record ancestry but to affirm divine origin. Many noble Hawaiian families trace their roots to gods like Kāne or Pele, giving them social status and spiritual authority.

Some chants are thousands of lines long, recited to honor the dead, mark transitions, or protect against spiritual harm. The knowledge embedded in them is poetic, layered, and full of symbolic meaning.

Today, efforts to preserve these traditions are supported by the University of Colorado Boulder, which works with local Hawaiian communities to digitize and archive oral histories and chant recordings.

Colonial Suppression and Cultural Revitalization

When Christian missionaries arrived in Hawaii in the 1800s, they outlawed many traditional practices. Hula, chant, and native religion were viewed as pagan and suppressed in schools, churches, and public spaces. Many stories were lost, sacred sites desecrated, and native beliefs marginalized.

But in the 1970s, the Hawaiian Renaissance began—a cultural movement aimed at restoring language, dance, navigation, and mythology. Hula schools (hālau) re-emerged, and elders began teaching moʻolelo again. Today, the Hawaiian language is taught in schools, chants are recorded, and children grow up learning the myths of their ancestors.

The University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa offers programs in Hawaiian religion, mythology, and cultural preservation. Festivals and ceremonies across the islands honor ancient traditions. Sacred sites are protected, not only for tourism, but as living repositories of ancestral wisdom.

Legacy of Hawaiian Mythology in the 21st Century

Hawaiian mythology is not a thing of the past. It informs the present and helps navigate the future. Myths are used to teach environmental stewardship, cultural pride, spiritual depth, and political awareness.

You might hear a grandmother remind her grandchild to respect the forest because Kamapuaʻa might be watching. Or see an offering left beside a freshwater spring in honor of Kāne. Or witness a hula telling the story of Hiʻiaka battling spirits.

These are not performances. They are continuations of belief. The gods still walk the land—not in temples, but in fire, rain, forests, and waves.

To explore the broader regional context of these traditions, see Polynesian Mythology Legends, which connects Hawaii’s stories with their oceanic cousins from Tahiti, Samoa, and beyond.

Frequently Asked Questions about Hawaiian Mythology

Q1: Who are the four main gods in Hawaiian mythology?

Q2: Why is Pele considered so important in Hawaiian beliefs?

Q3: How were myths passed down before written language?

Q4: Are Hawaiian myths still practiced or honored today?

Q5: How is nature connected to Hawaiian mythology?

Q6: How does Hawaiian mythology relate to other Polynesian myths?