The Dogon people of Mali are renowned not only for their distinctive cultural heritage but also for a profoundly symbolic belief system that has fascinated scholars, anthropologists, and even astronomers around the globe. Nestled in the cliffs of the Bandiagara Escarpment, the Dogon community has maintained its ancient traditions largely untouched by outside influence. Known as the “Star People,” they hold a complex cosmology rooted in myth, ritual, and celestial observation. At the heart of Dogon mythology lies a creation story that intertwines the spiritual and the cosmic, reflecting knowledge that many believe was far ahead of its time.

What sets Dogon mythology apart from other African spiritual systems is its multilayered fusion of science, religion, and metaphysics. These myths do not merely explain the natural world but serve as blueprints for architecture, farming, and social hierarchy. Every Dogon village is an embodiment of cosmological order, with houses, altars, and communal spaces reflecting celestial patterns and divine logic. The stories of the Nommo and Amma are not static tales but living beliefs, re-enacted through ritual dances, carvings, and oral storytelling that continue to thrive today.

The Dogon People and Their Spiritual Framework

Residing in the remote, rugged cliffs of central Mali, the Dogon people have long lived in harmony with nature, protected by geographical isolation that helped preserve their unique culture. Their mythology forms a foundation not only for religion but also for ethics, agricultural practices, governance, and the arts. Dogon mythology is not a simple collection of stories—it is a deeply integrated belief system that offers an all-encompassing view of life and the cosmos.

Each component of the Dogon worldview serves a sacred function. The creator god, Amma, established not just the universe but also the sacred order of society. From the configuration of family compounds to the conduct of seasonal farming, every Dogon action is connected to the myths handed down from ancestors. Children are initiated into this spiritual framework gradually, learning cosmological truths through coded language, masked ceremonies, and proverbs that reflect deep philosophical insights. Spiritual leaders known as Hogon act as the custodians of Dogon knowledge, guiding the community in both worldly and metaphysical matters.

The Sirius Mystery: Astronomy in Dogon Mythology

Perhaps the most enigmatic and compelling aspect of Dogon mythology is its apparent knowledge of astronomical facts that were only verified by modern science in the 20th century. According to oral traditions, the Dogon have long known that Sirius, which they call Sigi Tolo, is not a single star but a binary system with a dense companion star named Po Tolo. This star, said to be small and extremely heavy, supposedly revolves around Sirius in a 50-year elliptical orbit—a claim that eerily aligns with findings made using advanced telescopic technology.

How the Dogon acquired this knowledge is the subject of considerable debate. Some scholars, such as the French anthropologist Marcel Griaule, posited that this knowledge predated colonial influence and might suggest lost ancient contact with advanced civilizations. Skeptics argue that this information may have been introduced by outsiders and integrated into the Dogon belief system over time. Nevertheless, the fact remains that the Dogon people describe celestial phenomena with extraordinary precision.

According to a detailed Smithsonian Institution feature, Dogon granaries, shrines, and village layouts are meticulously aligned with key astronomical events, including the positions of the moon and specific stars. Further evidence comes from the Dogon’s description of a third star, Emme Ya, which they claim orbits Po Tolo and may have its own satellite. While this body remains undetected by scientists, the level of detail in these myths continues to spark curiosity and admiration.

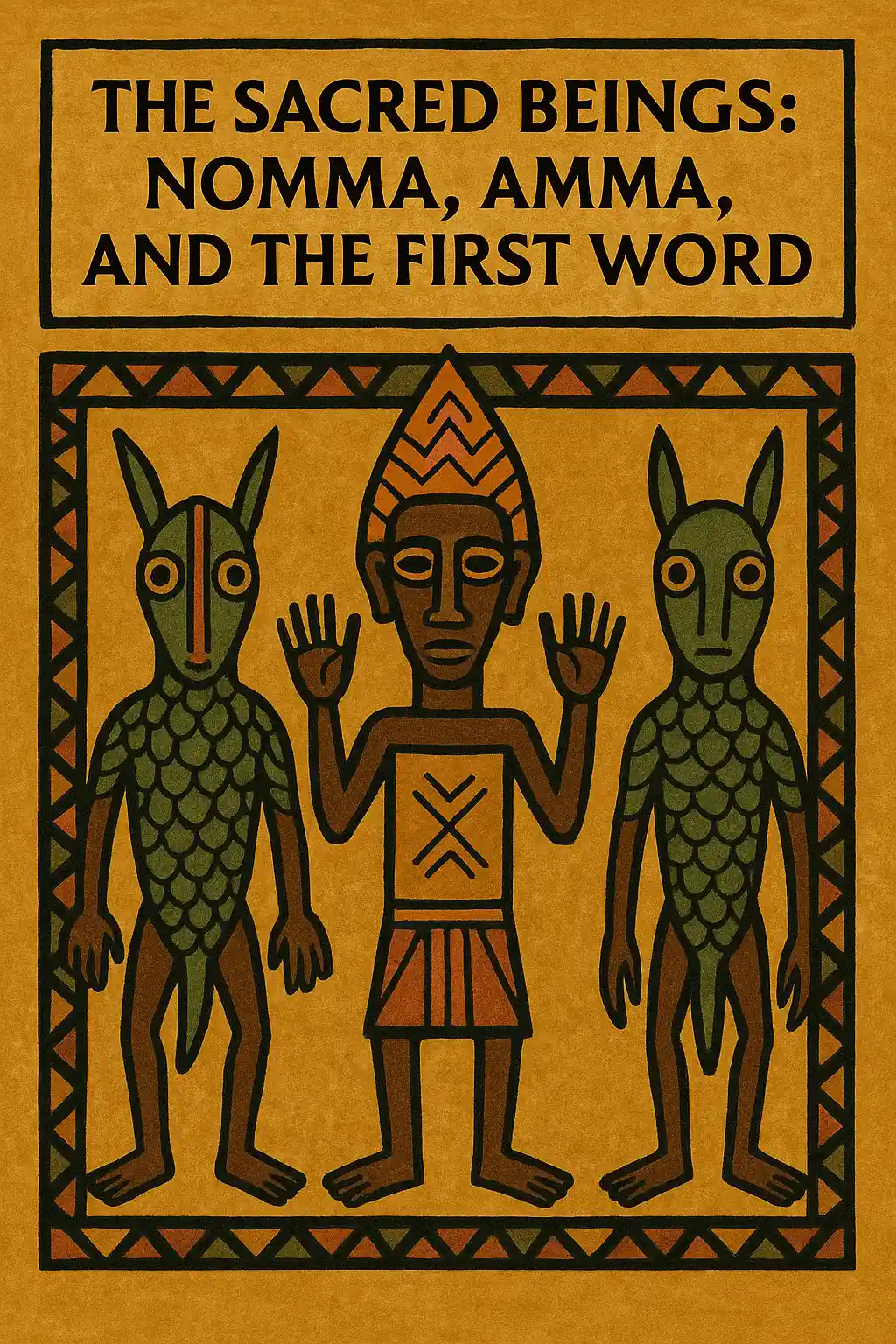

The Sacred Beings: Nommo, Amma, and the First Word

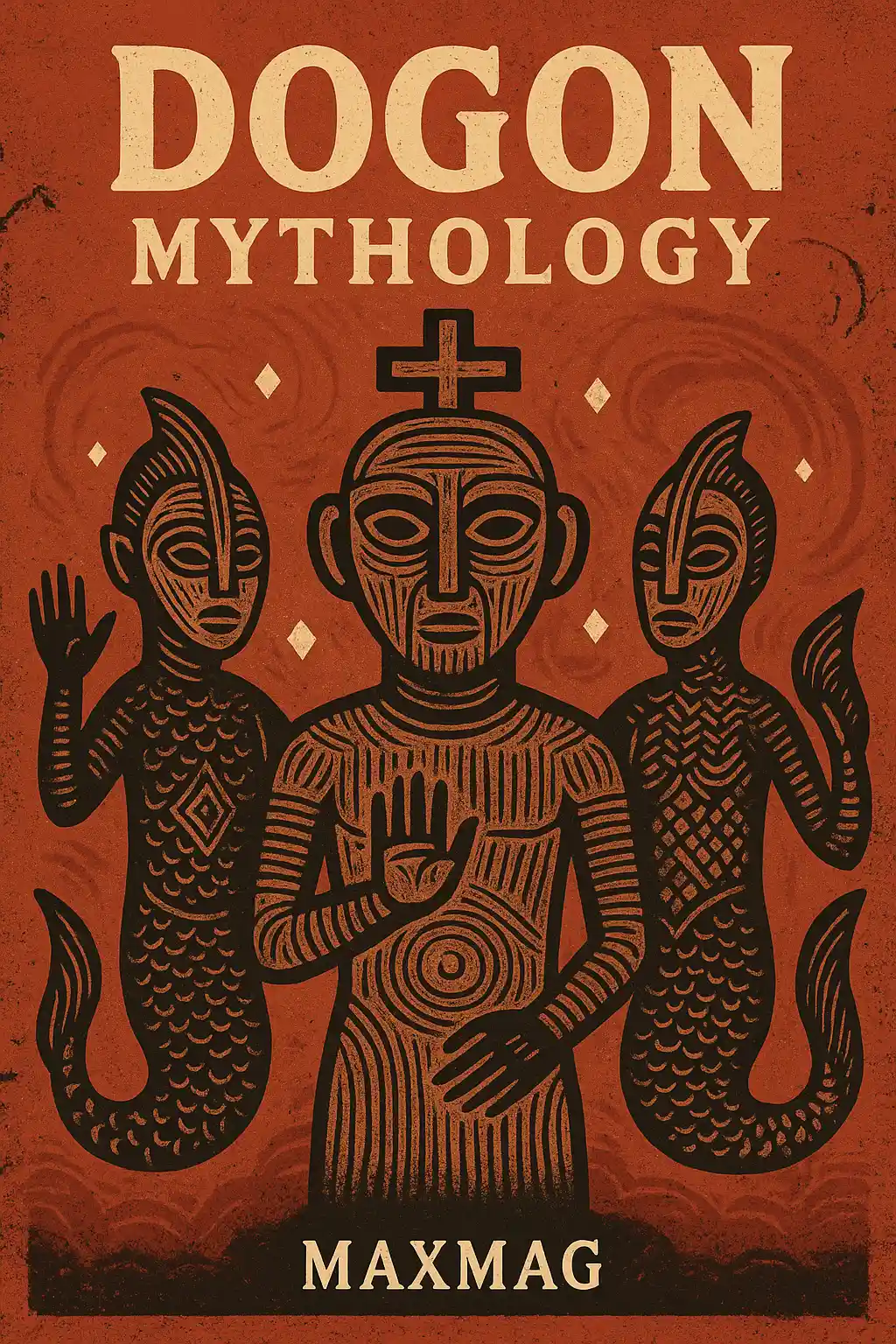

In the cosmological hierarchy of Dogon mythology, Amma occupies the highest position as the supreme creator. The act of creation began with the formation of the universe from a primordial egg, where all potential life and order were contained. However, Amma’s initial attempt to create the world was interrupted by chaos, symbolized by the disobedient figure Yurugu. To restore cosmic balance, Amma brought forth the Nommo—twin beings, often portrayed as amphibious creatures, half-human and half-fish, who descended from the sky in a spinning ark of fire.

These Nommo were not just divine messengers; they were responsible for organizing the chaos of the universe, creating the four cardinal elements (earth, fire, water, air), and introducing humans to speech, agriculture, and spirituality. The first Nommo sacrificed himself to save creation, and from his dismembered body, the rest of the cosmos was structured. This motif echoes creation myths across cultures where sacrifice leads to life—reaffirming the universal themes found in Dogon mythology.

Language holds immense power in this system. The Dogon believe that the Nommo’s first utterance brought the world into resonance, aligning chaotic vibrations into ordered sound and form. Thus, speech is sacred; it is seen not merely as communication but as the creative force of the divine.

Cosmology of Duality: Order and Disorder in Dogon Belief

At the core of Dogon mythology is the principle of duality—the ongoing tension between order and disorder, life and death, male and female, water and fire. These opposites are not viewed as contradictory but as interdependent forces whose interaction sustains the balance of the universe. This belief is embodied in the tale of Yurugu, a failed creation who represents disobedience, incompleteness, and disorder. Yurugu’s rejection of harmony is said to have introduced disharmony into the universe, necessitating the intervention of the Nommo.

Villages are laid out to mirror the human body, reflecting the idea that each person is a microcosm of the cosmos. Male and female granaries stand opposite each other to maintain symbolic equilibrium. Festivals, dances, and even farming techniques are conducted with attention to the balance of opposing forces. The elders teach that any upset in this harmony—such as drought, illness, or social unrest—is a reflection of cosmic disarray that must be remedied through sacrifice and ritual.

These ideas are etched into everyday life. From the construction of altars to the symbolism of iron tools and sacred masks, Dogon beliefs about balance extend into every material and social decision.

Masks and Myth: Ritual Expression in Dogon Ceremonies

One of the most visually striking aspects of Dogon spirituality is the use of masks during religious ceremonies. Far from being mere artistic expressions, these masks are tangible representations of mythological beings and ancestral spirits. Worn primarily during the Dama funeral rite and the generational Sigi festival, these masks serve as bridges between the physical and spiritual realms. Each mask holds a specific identity, representing anything from animals and ancestors to cosmic forces.

The Kanaga mask embodies the axis of the world, while the Satimbe mask honors female spiritual power. There are more than 70 types of masks used during Dogon rituals, each with its own precise meaning and cosmic alignment. These masks are crafted by highly trained artisans and passed through generations.

The American Museum of Natural History has exhibited many of these masks, highlighting their cosmological meaning and extraordinary craftsmanship. Every performance involving these masks is a sacred reenactment of creation, sacrifice, and renewal.

The Importance of Agriculture and Ancestral Worship

Agriculture is more than sustenance in Dogon society—it is sacred duty. Each planting and harvest season is preceded by elaborate rituals designed to honor Amma, the Nommo, and the ancestors who watch over the land. Millet, beans, and onions are planted according to celestial patterns, and special offerings are made to ensure fertility, rainfall, and protection from pests.

Ancestral altars are central to every Dogon village. Constructed from sacred earth and placed at key intersections, these altars are where families offer food, drink, and symbolic items to maintain connection with the spiritual realm. Death is not an end but a transition. The dead are believed to take on new roles as guardians and intermediaries who influence everything from weather to fertility.

Such beliefs are shared across various African spiritual systems. For example, Zulu Mythology also places strong emphasis on ancestors, sacrifice, and the unity between the physical and spiritual worlds. This interconnected worldview strengthens communal bonds and emphasizes the cosmic significance of daily tasks.

The Cultural Survival of Dogon Mythology

In the modern world, Dogon traditions have faced challenges from multiple fronts, including religious conversion, globalization, and tourism. Yet despite external pressures, Dogon mythology endures. Its survival is partly due to the secretive nature of its transmission. Knowledge is passed orally from elder to youth, often through sacred language and coded gestures that outsiders cannot easily decode.

Researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder highlight that many Dogon communities resist overt external influence by limiting sacred rituals to initiated members only. While tourism brings economic opportunities, it also risks commodifying spiritual objects. Local leaders now advocate for cultural preservation methods that emphasize authenticity and context.

Though many Dogon youth are exposed to Islam and modern lifestyles, core rituals, ancestral offerings, and cosmological teachings continue, often in more discreet forms. The resilience of Dogon mythology reflects a profound spiritual legacy that still shapes the identity and rhythm of everyday life in Mali.