Few human inventions combine wonder, science, and elegance like the hot air balloon. As the first aircraft capable of carrying people into the sky, it marked the beginning of our pursuit of flight—a dream that dates back centuries. The history of hot air balloons is not just a story of technical ingenuity but also one of public spectacle, royal interest, and daring adventurers who quite literally rose to new heights.

From Myth to Flame: Early Inspirations for Balloon Flight

Long before humanity grasped the principles of buoyancy and heat, civilizations across the globe were fascinated by the idea of flight. Greek mythology tells of Icarus, who flew too close to the sun with wings of wax. In China, Kongming lanterns—small airborne paper lanterns propelled by heat—date back to the 3rd century BCE and foreshadow the concept of hot air lift.

But it wasn’t until the 18th century in France that humans would transform this dream into something tangible.

The Montgolfier Brothers and Their Fiery Invention

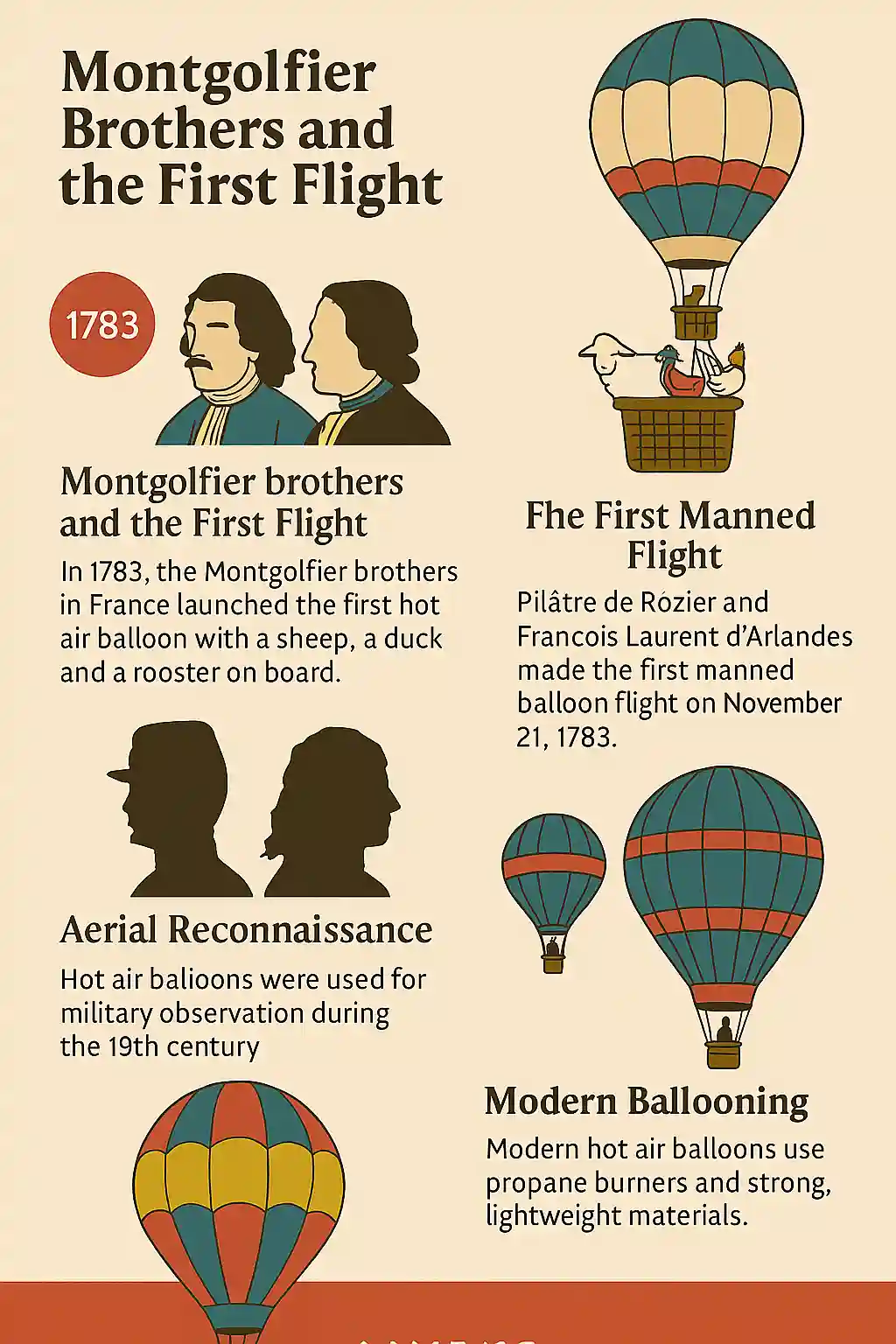

The history of hot air balloons officially took off in 1783 with Joseph-Michel and Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier, two French paper manufacturers. Inspired by the way smoke rises from a fire, the brothers believed they could harness this force to lift an object. Their earliest experiments involved paper balloons floating toward the ceiling, but they soon scaled up their ambitions.

In June 1783, the Montgolfiers launched a balloon filled with hot air in Annonay, France. It soared nearly 6,000 feet high and traveled over a mile before descending safely. This public demonstration stunned the crowd and caught the attention of King Louis XVI.

Later that year, with royal support, they launched a larger balloon from the Château de Versailles, carrying a sheep, a duck, and a rooster. The animals returned unharmed, proving that living beings could survive airborne travel.

Shortly after, on November 21, 1783, the first manned flight took place. Pilâtre de Rozier and François Laurent d’Arlandes soared over Paris for 25 minutes in a balloon constructed of silk and paper. Humanity had officially conquered the sky.

Competition Heats Up: Hydrogen vs. Hot Air

While the Montgolfiers pioneered hot air flight, rival inventors quickly explored hydrogen as a lighter-than-air alternative. Jacques Charles, a physicist, launched the first hydrogen balloon in December 1783—just weeks after the Montgolfier brothers’ manned flight. Hydrogen balloons could travel farther and stay aloft longer but were far more dangerous due to their flammability.

Still, hot air balloons retained their allure for public demonstrations and short-range travel. The Smithsonian Institution offers detailed historical exhibits explaining the early competition between hydrogen and hot air (source).

Aerial Warfare: Balloons in Battle

Though they may seem whimsical, hot air balloons have seen military use. During the French Revolutionary Wars, observation balloons were used to monitor enemy movements from above. The American Civil War also saw limited balloon use for reconnaissance.

Perhaps most famously, during the Siege of Paris (1870-71), hot air balloons carried mail and messengers over enemy lines. These daring flights helped maintain communication when the city was surrounded by Prussian forces.

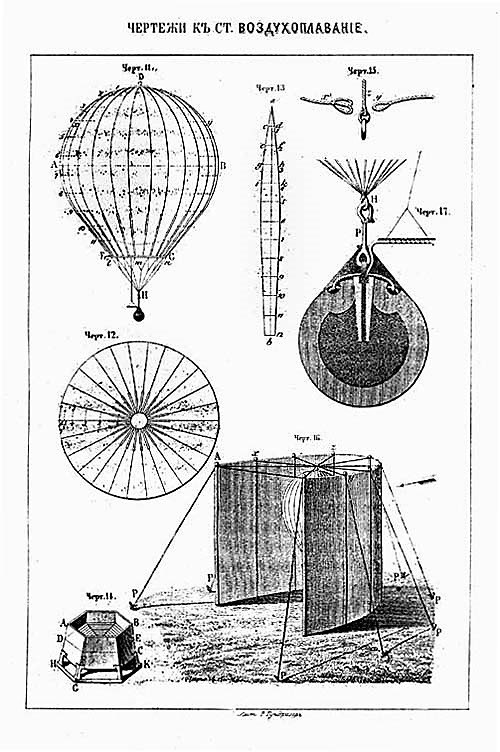

The Evolution of Ballooning Technology

By the 19th century, ballooning had become both a scientific pursuit and a source of entertainment. Adventurers like Jean-Pierre Blanchard and Sophie Blanchard performed public ascents, often ending in fiery or spectacular descents.

In 1906, Alberto Santos-Dumont developed a steerable balloon, blending hot air buoyancy with rudimentary propulsion—a precursor to the airship.

Modern ballooning technology now includes propane burners, synthetic materials for the envelope, and GPS tracking. The balloon’s basic principle—warm air rises—remains unchanged, but its execution has become far safer and more precise.

The History of Hot Air Balloons in America

Ballooning found eager adopters in the United States. The first American ascent occurred in 1793, when Jean-Pierre Blanchard flew a hydrogen balloon over Philadelphia with the blessing of President George Washington.

By the 20th century, hot air balloons became part of popular culture. Balloon races, fairs, and festivals—such as the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta (source)—attract hundreds of thousands of spectators annually. These events celebrate not only the thrill of flight but also the visual spectacle of hundreds of colorful balloons painting the sky.

The National Balloon Museum in Iowa chronicles the evolution of ballooning in the U.S. (source), highlighting both recreational and scientific uses over the decades.

Scientific Ballooning: Reaching the Edge of Space

Though often associated with leisure, hot air and gas balloons have also served science. NASA and other research institutions use high-altitude balloons to study cosmic rays, atmospheric chemistry, and even conduct near-space photography. Some balloons now reach altitudes of over 120,000 feet, skimming the edge of the stratosphere.

Unlike rockets, these balloons are reusable, relatively low-cost, and ideal for long-duration studies. The NASA Balloon Program Office provides insight into these missions (source).

Modern Records and Notable Flights

Modern ballooning has seen some incredible feats:

-

In 1999, Bertrand Piccard and Brian Jones completed the first non-stop, round-the-world flight in a balloon.

-

In 2012, Felix Baumgartner ascended 128,000 feet in a helium balloon before skydiving to Earth, breaking the sound barrier in freefall.

These modern achievements reflect how far ballooning has come from the days of silk envelopes and open flames.

Why Balloons Still Matter Today

In an age of jets and rockets, hot air balloons may seem quaint. But their significance remains. They represent the first successful attempt to leave the Earth’s surface—not by force, but by embracing the natural laws of heat and air.

Moreover, they continue to inspire awe. Watching a hot air balloon ascend at dawn, silently drifting over the landscape, is one of the purest reminders of humanity’s eternal quest for wonder.