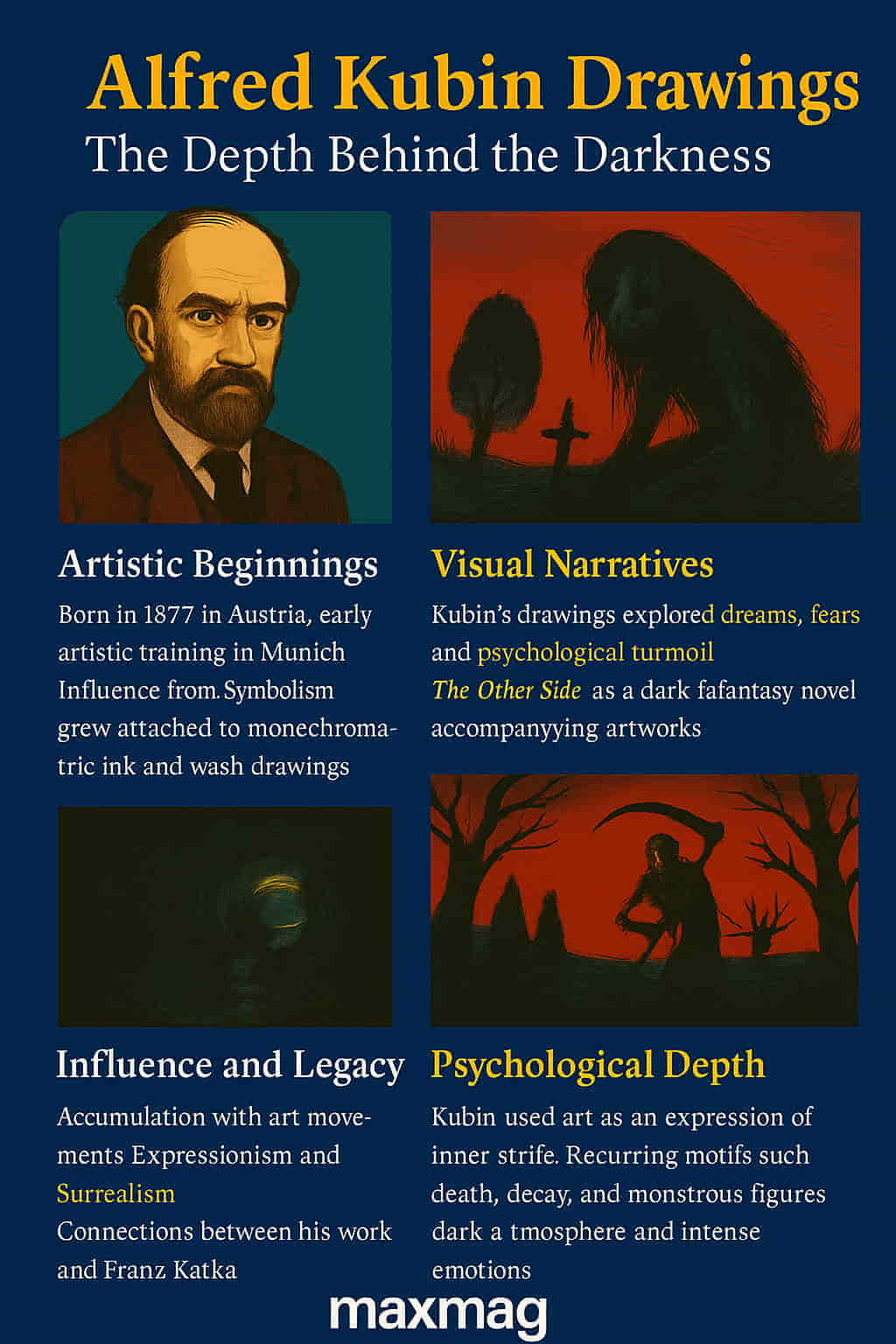

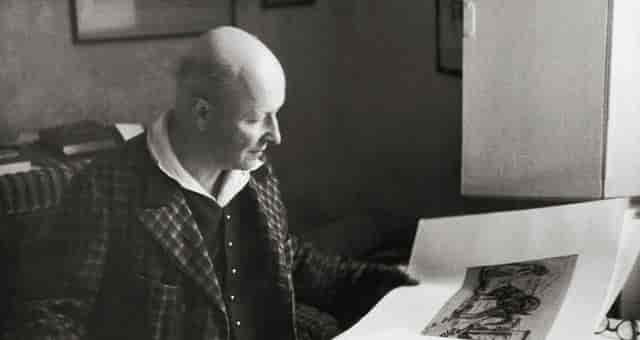

Few artists have so effectively captured the eerie, the subconscious, and the psychologically unsettling as Alfred Kubin. Born in 1877 in the Austro-Hungarian town of Litoměřice, Kubin would later emerge as a master of visual darkness, producing haunting monochrome works that blurred the lines between dream and nightmare. Today, Alfred Kubin drawings are revered not only for their stylistic uniqueness but for the way they document the hidden landscapes of the mind.

His art defies easy categorization — it is equal parts Symbolist, Expressionist, and proto-Surrealist. Yet at the heart of it all is a visual language uniquely his own. Kubin’s drawings are not meant to comfort. They are designed to provoke, disturb, and haunt.

Alfred Kubin’s Artistic Beginnings

Alfred Kubin’s early life was marked by instability and psychological trauma. After the death of his mother when he was just ten, he experienced emotional upheaval that would echo through his later works. His brief attempt at a military career ended in a nervous breakdown — a moment often interpreted by historians as the start of his journey inward, toward the psychological intensity that would define his art.

He eventually enrolled at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, where his exposure to the symbolist works of Odilon Redon and the psychological engravings of Max Klinger deeply impacted him. These artists offered Kubin more than inspiration — they gave him permission to abandon realism and embrace the strange, the grotesque, and the visionary.

In many ways, Kubin’s style was born out of necessity. He lacked the means for large oil paintings and instead turned to more economical materials — paper, ink, pencil, and wash. But within this limitation, he found profound creative freedom. He once wrote, “I live in the twilight between dream and reality.”

Mastery of Ink and Wash: The Signature Style

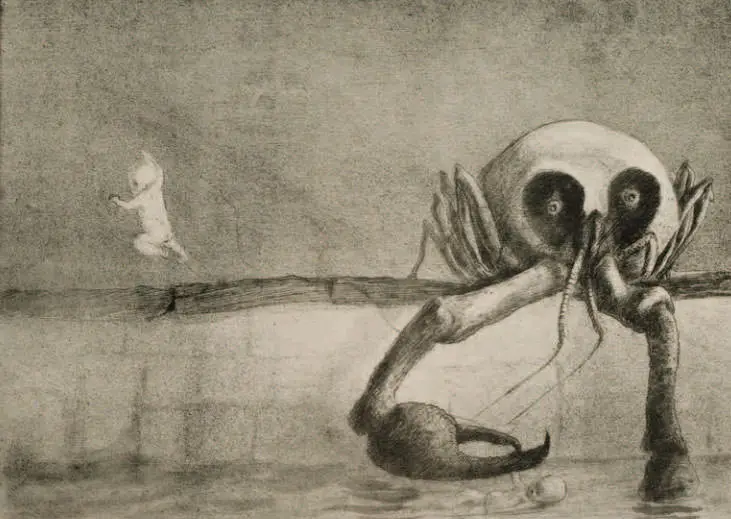

The monochrome medium of black ink and wash became Kubin’s artistic fingerprint. His use of varying washes, bleeding into one another across grainy surfaces, gave his work a misty, spectral quality. Unlike many of his contemporaries who embraced color and vibrancy, Kubin used black and gray to draw us into shadowy internal worlds.

He had a remarkable ability to evoke motion, tension, and psychological weight with minimal strokes. Alfred Kubin drawings often feature figures caught in moments of existential dread — sinking into the earth, collapsing under invisible forces, or morphing into otherworldly creatures.

His technique has since been studied in art schools for its use of negative space and tonal contrast. Kubin manipulated light and shade not just to model form, but to model feeling — creating emotional chiaroscuro with each drawing. His minimalist palette forced the viewer to focus not on beauty, but on meaning.

Major art institutions such as the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) continue to feature Kubin’s pieces in exhibitions that explore the evolution of modern visual storytelling.

Alfred Kubin Drawings as Visual Narratives

Alfred Kubin drawings are deeply narrative, though they seldom illustrate conventional stories. Instead, they reveal fragments of allegorical journeys or half-remembered dreams. They belong to a psychological continuum, where each drawing feels like a page torn from the same eerie journal.

The best example of Kubin’s narrative imagination is his illustrated novel The Other Side (Die andere Seite, 1909). In this singular work, he created both the story and its haunting images — an exploration of a fantastical city called Perle, where the laws of logic begin to dissolve. The city becomes a character itself: a decaying, dream-saturated landscape where time folds in on itself.

One haunting drawing from the book shows a procession of cloaked figures carrying coffins through fog-covered streets, watched by faceless children. The surreal tension between innocence and dread is classic Kubin. He wields his pen like a scalpel, exposing the hidden fears society keeps buried.

In his stand-alone drawings as well, Kubin touches on themes like bodily transformation, the collapse of identity, and the decay of social order. His use of anthropomorphic figures — half-human, half-beast — serves as both critique and confession. These drawings resonate with Carl Jung’s concept of the shadow self: the darker side of human nature we all suppress but which inevitably emerges.

Influences and Impact

Although he was never formally part of any art movement, Kubin’s influence rippled through early 20th-century modernism. He shared exhibition space with artists of the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter) group, including Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, though his style stood apart in its darker, more introspective tone.

His art particularly appealed to writers and philosophers — those concerned with existential and metaphysical questions. Kafka admired Kubin’s ability to visualize disquiet in abstract form. The eerie settings of Franz Kafka’s The Trial or The Castle seem visually prefigured in Kubin’s drawings of looming architecture and wandering figures.

He also had a profound impact on German Expressionist cinema. Films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu borrowed heavily from the distorted architecture and emotional surrealism found in his work. These films gave visual form to the same cultural anxieties Kubin explored: madness, urban alienation, and a creeping distrust in rational order.

Institutions like the Tate Modern and Smithsonian American Art Museum regularly explore these historical connections, helping to contextualize Kubin’s legacy within broader cultural shifts.

The Psychological Depth of Kubin’s Drawings

To understand Alfred Kubin drawings, one must look beyond aesthetics and delve into the psychological. His work is deeply autobiographical — a self-analysis in visual form. Themes of decay, mortality, mutation, and futility aren’t merely stylistic choices; they are expressions of Kubin’s lived experience.

Mental health professionals have increasingly examined his art as a window into pre-modern understandings of trauma. Kubin suffered from recurrent depressive episodes, and many believe he experienced symptoms akin to PTSD. Rather than avoid these experiences, Kubin leaned into them, transforming his pain into probing visual metaphors.

In works like Man and Dog or Guilt, the emotional atmosphere is claustrophobic. Figures appear crushed by space, or melded into their surroundings as if trying to escape their own minds. The sense of confinement is spiritual as well as physical. His drawings feel less like finished products and more like exorcisms — a way to purge emotion from the body onto paper.

Psychologists now include Kubin’s art in case studies related to dream interpretation and trauma expression. His ability to channel unconscious anxieties into structured compositions gives his work lasting therapeutic and academic value.

Where to See Authentic Kubin Drawings Today

Despite the age of his work, Kubin remains highly visible in the art world. Numerous museums around the globe showcase his pieces both in permanent collections and rotating exhibitions.

-

Albertina Museum in Vienna — This institution holds the most comprehensive Kubin archive, including rare first editions and sketchbooks.

-

MoMA, New York — Regularly includes Kubin in thematic exhibits exploring Symbolism, Surrealism, and early modernism.

-

LACMA, Los Angeles — Maintains a rotating collection that occasionally spotlights Kubin in dialogue with modern filmmakers and illustrators.

-

Leopold Museum, Vienna — Offers in-depth retrospectives, often featuring Kubin alongside Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt.

Most of these museums now provide virtual tours or high-resolution image databases, making it easier than ever to explore Alfred Kubin drawings from anywhere in the world.

FAQ: Alfred Kubin Drawings

What materials did Alfred Kubin use?

He typically worked in black ink, pencil, and wash on paper. These allowed him to evoke complex emotional tones with minimal elements.

Why are Alfred Kubin’s drawings considered unique?

His art blends surrealism, psychology, and mythology in a way that feels deeply personal and timeless. The use of monochrome adds to the stark intensity.

Are his drawings valuable?

Yes. Original Alfred Kubin drawings are rare and highly sought after by collectors and institutions. They are often priced in the tens of thousands.

What books contain his illustrations?

Kubin’s major work is The Other Side (1909), a novel he wrote and illustrated. It remains his most complete artistic statement.

Is Kubin part of any major movement?

While not officially affiliated, his work bridges Symbolism, Expressionism, and early Surrealism. He influenced many 20th-century artists and filmmakers.

Where can I study Kubin’s work in detail?

Universities and museums like the Albertina, MoMA, and Tate Modern provide archives, publications, and curatorial essays examining his art.