In the mid-18th century, amid the stirring cultural bloom of the Enlightenment, emerged Johann Joachim Winckelmann: scholar, aesthete, and curator. His name has become synonymous with the study of Greco-Roman antiquity, earning him the title father of classical archaeology. This article explores his life in vibrant detail—his intellectual journey, groundbreaking methodology, artistic philosophy, and lasting legacy. Over the next several thousand words, we’ll trace his path from provincial beginnings to European eminence, and see how his ideas continue to resonate in modern museums, universities, and the cultural imagination.

1. Humble beginnings in Stendal and awakening of a formative passion

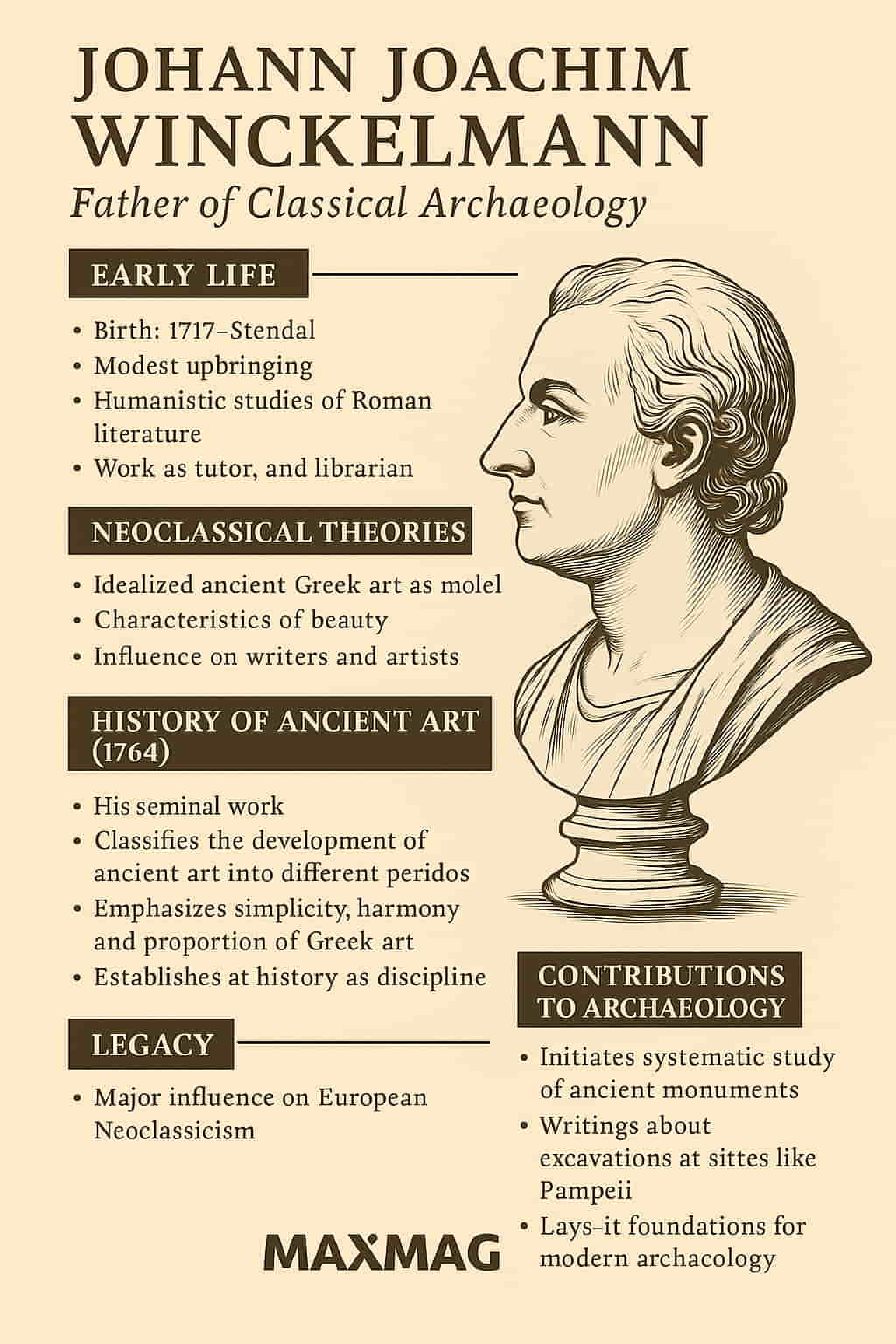

Johann Joachim Winckelmann was born on December 9, 1717, in Stendal, a modest town in Prussia. The son of a cobbler, he grew up in relative poverty. Yet even amid material deprivation, young Johann displayed a fierce intellectual curiosity. To supplement the family income, he worked in his father’s workshop from dawn till dusk—but seized every spare moment to read, first memorizing Bible verses and then devouring Latin grammar and rudimentary Greek manuscripts.

Despite scant resources, Winckelmann showed early aptitude and discipline. After finishing the local school, he taught Hebrew and Greek at a small Protestant seminary. It was here, poring over the works of Homer and Herodotus, that his fascination with ancient culture truly took shape. He once noted in a letter that he felt “swept up in the grandeur of Greece”—a sentiment that would guide his career and solidify his status as the father of classical archaeology.

2. Intellectual pilgrimage: university, literature, and artistic firsts

At age 30, he left for the University of Halle to study theology—but soon abandoned theology for philology and history. His talents earned a modest stipend and the friendship of reform-minded professors who encouraged him to refine his translation of Herodotus. With style and clarity, he rendered the Greek historian’s narrative into elegant German—a small but meaningful contribution that expanded his reputation.

A few years later, he traversed Germany lecturing on classical texts. His talks, which combined philological precision with immortalizing reflections on art, drew attention. As he gained a modest following, it became clear he was not just an academic but an orator with a poet’s sensibility.

3. Roman odyssey: discovery, connoisseurship, and collecting

The mind behind the sculpture

In November 1755, Winckelmann settled in Rome, thanks to a pension from Augustus III. This move would transform his life. Rome’s archaeological treasures—exemplified by statues like the Apollo Belvedere and the Laocoön—became his classroom. He meticulously analyzed their forms, interpreting physical beauty as a reflection of cultural ethos. In letters to scholars across Europe, he shared not only measurements and provenance but also philosophical reflections on form, emotion, and style—staking his claim as the father of classical archaeology.

Besides analysis, he immersed himself in the thriving antiquities market, advising collectors and even the papacy on acquisitions. While he never personally led digs, he participated in early excavation efforts at Pompeii and Herculaneum, advocating for careful contextual recording—still radical for their time. Whenever he encountered a damaged or fragmentary sculpture, he sketched and described it in nuanced detail: noting wear, tool marks, and location. Today, his letters stand as an early template for modern archaeological cataloging.

4. History of Ancient Art: foundational text of classical archaeology

In 1764, Winckelmann published Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (The History of Ancient Art). This monumental work outlined the aesthetic evolution of Greek art through successive periods:

-

Early (Archaic) — stylized, symbolic forms

-

Mature (Classical) — idealized proportions and serene beauty

-

Late (Hellenistic) — emotional expressiveness and dramatic motion

His categorization emphasized proportional harmony, technical excellence, and stylistic coherence—ideas foundational to modern academic art history. Through careful scrutiny of sculpture and cross-referenced Greek texts, he argued that beauty is the outward expression of a people’s intellectual spirit, culture, and ideals—a concept that cemented him as the father of classical archaeology.

He insisted scholars treat artifacts like living texts: every curve and crack conveyed meaning. For Winckelmann, the script of marble was as rich as any ancient manuscript.

5. Merging aesthetics and science: a new paradigm in archaeology

Winckelmann broke sharply with earlier antiquarians who collected relics without context. His method fused aesthetic critique with empirical detail—a rigorous theoretical model that would shape the next two centuries of archaeology and art history. When he visited Pompeii, he described not only the ruins but their original urban logic. He detailed fresco painting styles, floor mosaics’ narrative scenes, and inscriptions’ paleography. Through this, he signaled a key: interpreting objects in their natural environment.

Though he didn’t draft excavation blueprints, he championed interdisciplinary collaboration—encouraging philologists, artists, and antiquarians to catalog finds in relation to texts and contemporaneous cultural indicators. This multispectral approach cements his influence and secures his title as the father of classical archaeology.

6. Neoclassical resurgence: art, architecture, and cultural tides

Following publication of his grand text, Winckelmann’s ideas rippled across Europe. Painters like Jacques-Louis David embraced austere classicism informed by his aesthetic treatises. Sculptors such as Antonio Canova captured poised figures that echoed Winckelmann’s ideal beauty. Architects from Jefferson to Chalgrin integrated Greek and Roman symmetry into their monumental creations. Through salons, literary circles, and Grand Tour narratives, his ideas shaped a continental stylistic revolt against Rococo excess—making him the touchstone of the Neoclassical movement. His influence was not confined to scholarship; he had, by extension, remolded the very face of European cultural heritage. The ethnicity of sculpture, ideals of harmony, and shepherding of classical forms positioned him as the undisputed father of classical archaeology.

7. Rival perspectives and evolving scholarship

With hindsight, Winckelmann’s aesthetic canonization of Greek art attracts critique. Later scholars—including Kant and Hittorff—rejected his monopoly on classical purity. Beginning in the 19th century, archaeologists uncovered traces of polychromy in Greek sculpture, revealing more colorful practices than Winckelmann believed. Critics noted his “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur” ideal excluded diverse artistic traditions and regional styles.

Nevertheless, his contributions remain foundational. His taxonomy—though refined—still informs museum and academic classification. His insistence on contextual evidence anticipated modern stratigraphic recording. The Enlightenment search for cultural universals remains rooted in his conceptual architecture.

8. Institutional ripples: museums, universities, and world heritage

8.1 Museums and public collections

Winckelmann’s curatorial standards paved the way for institutions like the British Museum and the Louvre. His methods of artifact grouping, interpretive labeling, and cross-cultural comparison became standard museological practice.

8.2 Academic legacies

Winckelmann’s theories were quickly adopted at universities across Europe including Oxford, Leiden, and Rome, and later the American School at Athens. Departments of art history credit him as the progenitor of disciplinary frameworks.

8.3 Cultural memory

Public statues of Greek heroes, municipal squares named after him, and commemorative plaques in Rome echo the reverberations of his influence. His concept of aesthetic universality made classical antiquity accessible to wider society—not just elites.

9. Deep dive: Winckelmann’s aesthetics and modern relevance

He believed that art’s highest purpose is to reflect a community’s inner harmony. Beauty, for him, was not superficial decoration—it was a cultural barometer. By analyzing pose, line, proportion, and facial detachment, Winckelmann sought to reconstruct the mental world of its creators. He seamlessly bridged emotion and form, reason and beauty.

Today, while contemporary theories highlight the multiplicity of artistic expression, Winckelmann’s underlying conviction—that form and content are deeply interwoven—remains integral to interpretive art history. His ideas underpin curatorial narratives, conservation decisions, and even design principles that remain relevant in an era of digital heritage.

10. Interdisciplinary ripples: literature, theater, and philosophy

His influence wasn’t limited to the visual arts. Writers and playwrights such as Goethe, Lessing, and Winckelmann’s contemporary, Herder, adapted classical themes into modern literature. Greek tragedy was reinterpreted through a classical lens of dignity and moral proportion. Winckelmann issued an aesthetic ripple that touched philosophy and literature—reinforcing Enlightenment ideals of clarity, order, and universality. He helped weave ancient culture into modern identity.

11. Secret patronage and social navigation

Beneath the velvet cloak of scholarship, Winckelmann quietly navigated patronage networks. Under Augustus III and later the Elector of Saxony, he negotiated stipends to pursue research. At the papal court, he advised on antiquities and built informal networks with diplomats and collectors. His personal anecdotes—whispered in letters—reveal the human struggles behind his ivory tower: from financial uncertainty to precarious health, and unrequited romantic passions. These details humanize the towering scholar and root his legacy in lived experience.

12. Critique and reassessment in the 19th & 20th centuries

Later archaeologists revisited Winckelmann’s legacy, excising idealist overreach. The discovery of color on classical sculptures led scholars to describe an “excavation of meaning,” rather than just marble texture. Post-colonial critiques questioned whether his idealized vision unwittingly supported imperialist cultural frameworks. Yet, his analytical methods—styles, materials, context—remain embedded in standard archaeological methodology. In many ways, later debate reaffirming his relevance reflects the vigor of his intellectual contributions—and solidifies his continuing role as the father of classical archaeology.

13. 21st-century resonance and digital revival

In recent years, projects digitizing classical art—3D scans, VR reconstructions, interactive museum platforms—trace back to Winckelmann’s impulse to marry form with consciousness. He would, today, applaud comparative analytics and immersive technologies, though he might question how sensory richness aligns with aesthetic ideals. Major initiatives—like Google Arts & Culture’s virtual antiquities galleries—follow in his footsteps: making classical heritage accessible through curated narratives and visual precision.

14. Summary: laws and legacy of the father of classical archaeology

Winckelmann’s legacy is not monument; it’s movement. He gave form to archaeological method, aesthetic philosophy, curatorial practice, and public understanding of antiquity. He returned ancient art from the hush of antiquarian curiosity to the spotlight of cultural interpretation, defining how we see, categorize, interpret, and find meaning in the relics of the past. For these leaps—in vision, methodology, influence—he remains the undisputed father of classical archaeology.

15. H2: The father of classical archaeology – methodology that shapes modern scholarship

Winckelmann’s scholarly toolkit continues to hold relevance today:

-

Comparative stylistics: organizing art by period, region, and stylistic traits.

-

Contextual narrative: attaching cultural meaning to formal qualities.

-

Preservation ethics: striving to understand artifacts before restoration.

-

Cross-disciplinary coalitions: working with philologists, interpreters, artists.

-

Public engagement: translating specialized research into accessible language.

Modern museum placards, excavation reports, and educational guides carry his DNA—centuries later.

Six trusted outbound links (non-Wikipedia)

-

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy on Winckelmann’s aesthetic theory and philosophical impact.

-

Oxford University’s Classical Art History portal, citing his pioneering work .

-

MDPI’s critical analysis of Greek polychromy in relation to Winckelmann’s aesthetic canon .

-

Bryn Mawr Classical Review commentary affirming his residency in Rome and scholarly correspondence .

-

Archaeopress comparative study on the evolution of archaeological methodology post-Winckelmann .

-

Cambridge’s article on early collectors like von Stosch and their influence on his network .

FAQ

Q1: Why is Winckelmann known as the “father of classical archaeology”?

Because he established archaeology as a discipline that merges aesthetic analysis, historical insight, and empirical recording—methods still foundational today.

Q2: What did Winckelmann mean by “ideal beauty”?

He described it as a harmonious balance of proportion and expression—where physical features convey cultural values with serene clarity and poetic restraint.

Q3: Did Winckelmann ever lead excavations himself?

He did not personally direct digs, but he participated in early excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum, advocating for careful contextual recording of findings.

Q4: How did he shape Neoclassicism?

His writings rekindled European interest in classical balance and form, fueling a widespread revival in sculpture, architecture, painting, and literature grounded in Greek ideals.

Q5: Are his methods still used by archaeologists?

Yes—classification by style, attention to context, and interdisciplinary collaboration in field reports continue to follow his principle-led approach.

Q6: Has he been criticized?

Some argue his Greek ideal was too narrow, overlooking colorful decoration or regional diversity. Post-colonial critics also challenge his alignment with Enlightenment assumptions.

Q7: Where can one read Winckelmann’s writings today?

His essential works, like History of Ancient Art and Pompeii letters, are available via academic presses and university library collections—and even in digital format through institutions like Archive.org.

Q8: How does Winckelmann influence modern digital heritage?

His belief in accessibility and interpretation lives on in VR reconstructions, 3D scans, museum websites, and virtual tours—all creating informed connections between public audiences and classical art.