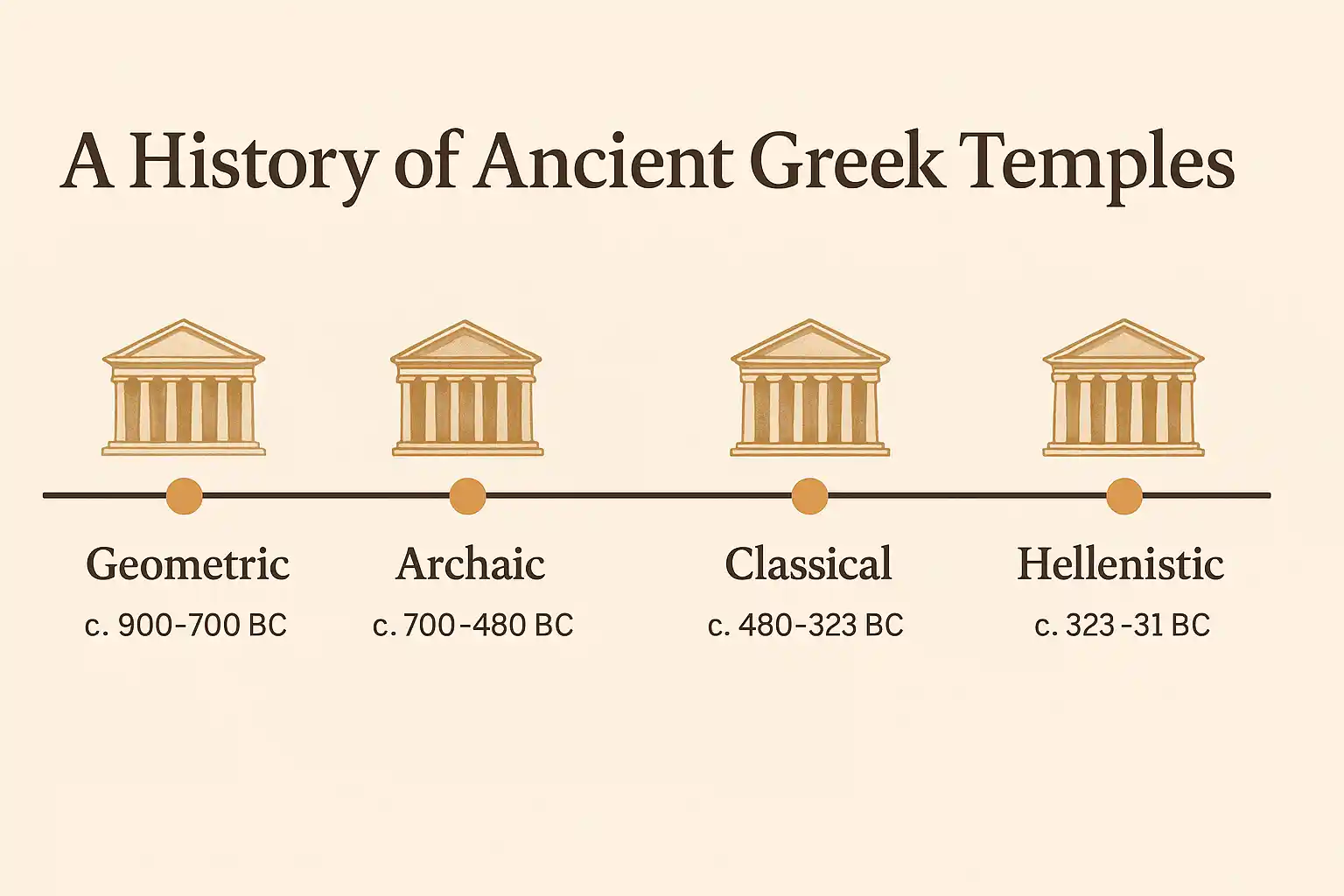

The majestic temples of Ancient Greece remain some of the most iconic and enduring symbols of classical architecture. From the Parthenon on the Acropolis to the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, these structures weren’t just places of worship—they were marvels of geometry, mathematics, art, and political expression. But how exactly were these awe-inspiring temples built, especially with limited tools and no modern machinery?

This article explores the intricate process of how the magnificent temples in Ancient Greece were constructed, from the quarrying of stone and transportation logistics to the role of skilled labor, engineering innovations, and religious symbolism. Each column and carving tells a story—not only of faith but also of intellectual mastery and cultural power.

The Vision: Temples as Expressions of Divine Order

Greek temples were not just homes for gods—they were physical representations of divine order and harmony on Earth. The temples honored deities like Athena, Apollo, Zeus, and Hera, each with carefully chosen orientation and design elements aligned with cosmology and ritual practices.

A temple’s purpose was to house a cult statue of the god or goddess and provide a sacred place for offerings. The temples themselves were not for congregational worship; rituals typically occurred outside at altars. This makes the temple more of a divine residence than a gathering space.

Site Selection and Orientation

Choosing the temple’s location was the first vital step. Ancient Greek temples were often built on elevated ground—acropolises or hills—signifying the closeness to the heavens. Engineers used astronomy to align temples with celestial events. For instance, the Parthenon is aligned east-west so that the rising sun could illuminate the cult statue of Athena on key holy days.

This integration of architecture and astronomy reveals the Greeks’ deep spiritual relationship with nature and cosmos—a fact still studied today by researchers at institutions like the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Quarrying and Transporting Stone

The majority of temples were built from limestone or marble. Quarries like those on Mount Pentelicus and Naxos were key sources for high-quality marble. Quarrying was a labor-intensive task, requiring iron tools like chisels, levers, and hammers to extract massive blocks.

Transporting these blocks to the temple site required logistical brilliance. Workers used wooden sledges, carts, and sometimes even ships to move materials. Special roads were carved through the mountains to accommodate the movement of heavy loads, and pulley systems were used at construction sites to raise and position the stones with precision.

Some studies suggest marble blocks were coated with wet clay and dragged over stone tracks, minimizing friction—a method confirmed by experiments documented by researchers at MIT’s Department of Materials Science.

Foundation and Platform

Temples were constructed on a stepped platform called a stylobate. This raised base ensured structural integrity and enhanced visibility. Foundations were often built from limestone, which was then topped with marble.

Interestingly, the Greeks applied optical illusions. The stylobate was not perfectly flat—it curved slightly upward in the center to counteract the natural sagging appearance of straight lines over long distances. This subtle curve created an illusion of perfection when viewed from below.

Columns, Capitals, and Orders

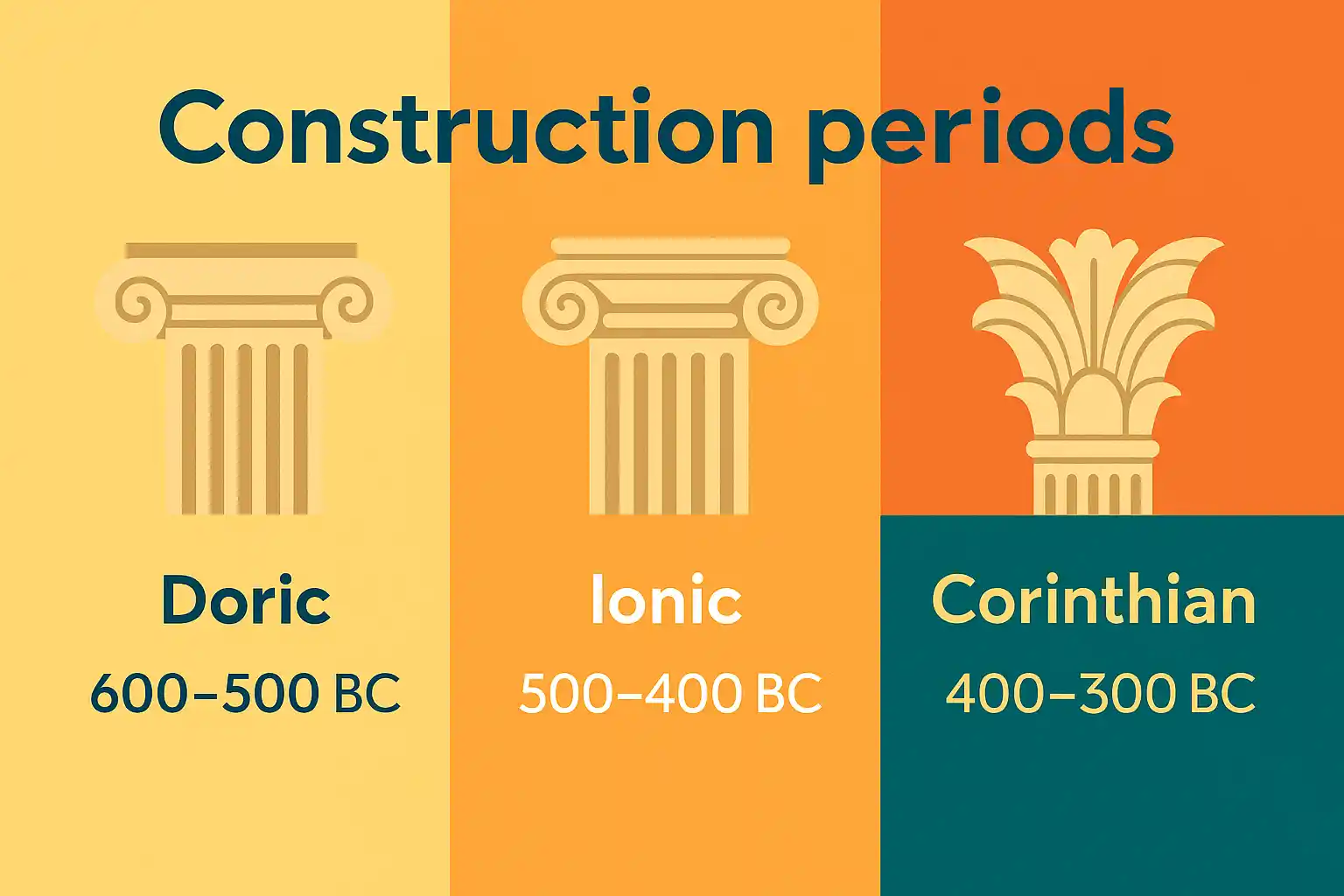

The columns were among the most iconic features of Greek temples, built in three primary architectural styles: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.

-

Doric: Thick, plain columns with no bases, found in temples like the Parthenon.

-

Ionic: Slimmer columns with scrolled capitals, used in the Temple of Athena Nike.

-

Corinthian: Ornate columns with acanthus leaf capitals, seen later in the Hellenistic period.

Each column was made of several drums stacked atop each other with metal dowels for alignment. Fluting (vertical grooves) was carved into the columns after stacking, ensuring a seamless appearance.

What’s extraordinary is that no two columns were exactly alike. Ancient Greek architects accounted for perspective and made slight adjustments in column dimensions and spacing for visual harmony.

Wooden Scaffolding and Rope Pulleys

Without cranes, Greek builders relied on ingenious methods of hoisting. Wooden scaffolding provided access to higher levels, and teams of workers operated rope and pulley systems. This coordination required precise communication and skilled labor, often overseen by a master architect or tekton.

Temples could take decades to complete, and their construction involved a highly organized labor force including slaves, skilled artisans, masons, and even mathematicians. Their combined efforts transformed raw stone into structures that withstood the test of time.

Sculptural Decoration and Symbolism

Temples were not just feats of engineering—they were also masterpieces of sculpture. The metopes, friezes, and pediments were richly decorated with mythological scenes depicting gods, heroes, and battles like the Gigantomachy or the Trojan War.

For instance, the Parthenon frieze shows a Panathenaic procession, celebrating Athenian unity and religious devotion. The use of high-relief sculpture added depth, movement, and storytelling to the temple’s surface.

These works were not purely decorative—they conveyed political and moral ideals, symbolized the city’s divine favor, and immortalized its historical narrative.

Explore more classical sculpture insights at the Getty Museum’s antiquities collection.

The Role of Color and Painting

Contrary to popular belief, Greek temples were not blank white monuments. They were vibrantly painted, a practice called polychromy. Reds, blues, and golds were used to color statues, columns, and carvings. Traces of pigments have been found on many ruins, and modern reconstructions now attempt to recreate their original hues.

Color served symbolic purposes—blue for divine realms, red for vitality, and gold for the gods. Even the cult statues inside temples, often made of chryselephantine (gold and ivory), glowed under natural light filtered through architectural openings.

Religious Rituals and Temple Life

While the temples were not used like modern churches, they played a vital role in Greek religious life. Priests and priestesses conducted daily offerings and maintained the cult statue of the deity. Festivals like the Panathenaia or Delphic Games included processions, sacrifices, music, and dramatic performances, often centered around the temple complex.

Temples were also repositories of wealth—offering treasuries and sacred dedications, sometimes used by city-states to display power and prestige. The Temple of Apollo at Delphi, for instance, housed offerings from across the Hellenic world and served as a hub of divine prophecy.

Mathematical Precision and Proportional Harmony

Greek temples followed rigorous proportions. The Golden Ratio (1.618…), a principle of aesthetic harmony, was used to determine dimensions between columns, height to length, and space in architectural elements. This ratio helped create visual balance and remains influential in art and architecture today.

In fact, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences notes the legacy of Greek proportions in Renaissance and modern design (source).

Legacy and Preservation

Many ancient temples fell into ruin through earthquakes, wars, or conversion into churches and mosques during later empires. Yet the basic structure often remained—proof of their engineering brilliance.

Modern efforts have been made to preserve and restore temples like the Parthenon, with the help of 3D scanning, architectural archaeology, and international collaboration. These restoration efforts continue to reveal new insights about ancient materials, techniques, and innovations.

Conclusion

The magnificent temples of Ancient Greece were far more than beautiful buildings. They were spiritual sanctuaries, technological triumphs, and cultural statements carved in stone. Constructed with astonishing precision, rooted in mathematical harmony, and adorned with sacred symbolism, these temples remain some of the greatest testaments to human creativity and devotion.

Even today, their influence can be felt in the neoclassical architecture of courthouses, museums, and monuments across the globe—a living echo of the gods, builders, and ideals of ancient Hellas.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How long did it take to build a Greek temple?

Q2: Were Greek temples open to the public?

Q3: What tools did the Greeks use for construction?

Q4: Why did they curve the foundations and columns?

Q5: Were temples painted originally?

Q6: Which was the most famous ancient Greek temple?