Long before his famous line that “nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution”, Theodosius Dobzhansky was a shy boy collecting beetles in Kiev. A strong Theodosius Dobzhansky biography begins not in the lecture halls of New York, but in the upheaval of the Russian Empire, where a young naturalist learned to see variation everywhere. At a time when Mendelian genetics and Darwin’s theory of natural selection seemed to be pulling apart, he would help fuse them into a single story about how life changes. That story – of fruit flies in dusty field stations, fierce arguments about race and religion, and a conviction that evolution could sit alongside faith – still shapes how we think about human nature today.

For readers who meet him first through a Theodosius Dobzhansky biography rather than a laboratory bench, what matters is not just his equations but the drama around them: exile and reinvention, scientific revolutions, and the moral questions that come with studying human difference. He was a pioneer of evolutionary genetics, a migrant scholar who helped build the modern synthesis, and a public intellectual who insisted that biology had something important to say about democracy, equality and belief.

At a Glance: Theodosius Dobzhansky

- Who: Russian-born American geneticist and evolutionary biologist.

- Field and era: Evolutionary genetics pioneer of the mid-20th century, central to the modern synthesis of evolution.

- Headline contributions: Bridged genetics and Darwinian evolution, transformed fruit fly studies into a model for understanding how species change, and popularised the idea that “nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution”.

- Why he matters today: His ideas underpin how scientists think about genetic variation, human diversity and the relationship between science, faith and society.

Early Life and Education of Theodosius Dobzhansky

From Nemyriv to Kiev: a childhood of insects and upheaval

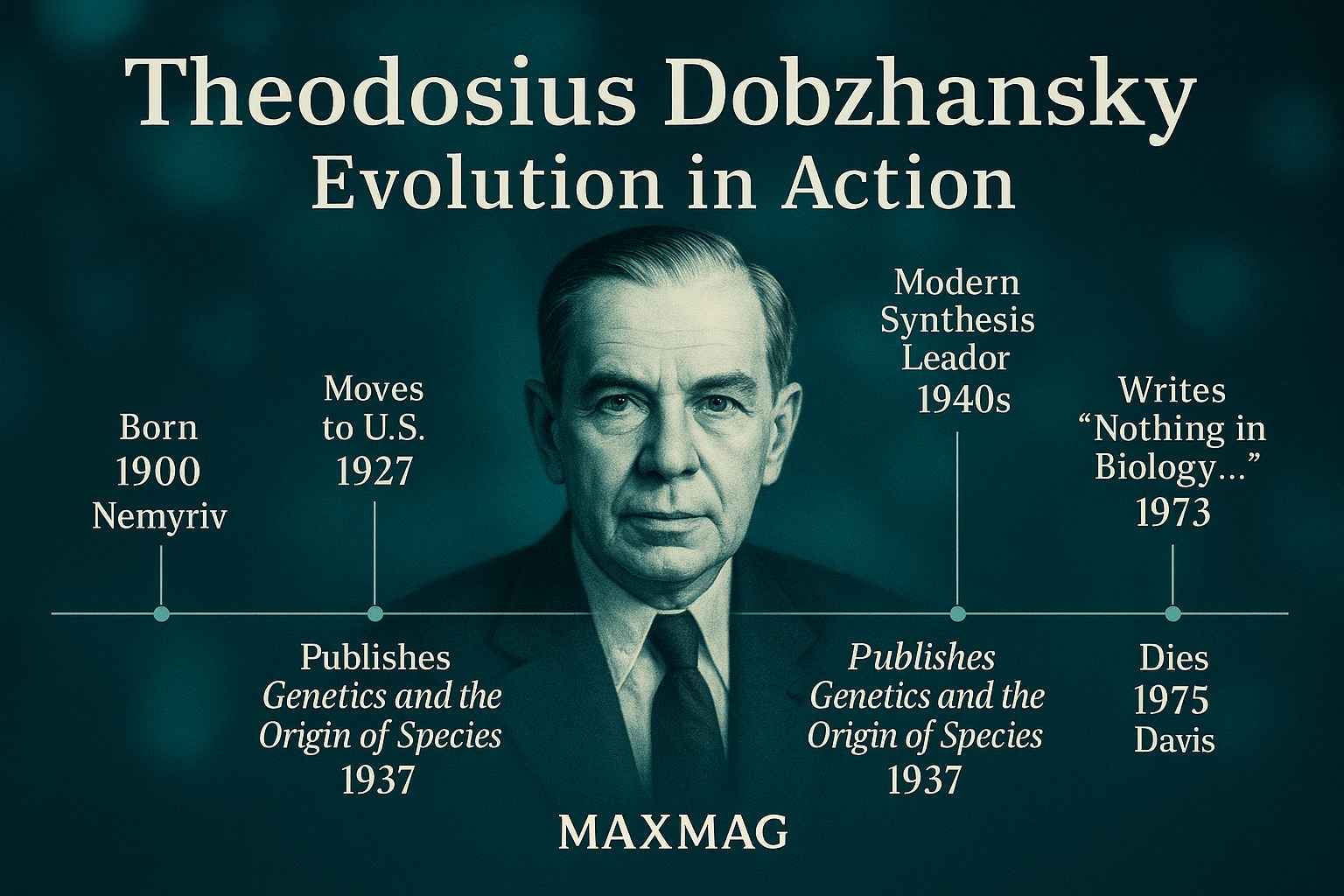

Theodosius Dobzhansky was born in 1900 in Nemyriv, a small town in what is now Ukraine, into a modest family headed by a mathematics teacher and a mother who prized learning. His unusual first name came from a local saint to whom his parents had prayed for a child. In a country shaken by political unrest and war, the young boy found a kind of quiet order in nature, pinning butterflies and beetles, turning their patterns into a private catalogue of the living world. That early fascination with variation – why one insect’s wings differed slightly from another’s – would follow him for the rest of his life.

University years: discovering genetics in a changing world

When the family moved to Kiev, Dobzhansky’s world widened. He studied biology at the University of Kiev just as genetics was beginning to reshape the life sciences. In lecture halls darkened by power cuts and civil war, he absorbed both classical natural history and the new Mendelian view of inheritance. He specialised in entomology, learning how to classify insects and read tiny anatomical differences as clues to evolutionary history. Under the influence of the geneticist Yuri Filipchenko in Leningrad, he encountered fruit flies – Drosophila – and the idea that laboratory organisms could serve as powerful tools for understanding evolution itself.

By the mid-1920s, the future subject of any Theodosius Dobzhansky biography was already clear: he would be a scientist who moved easily between fieldwork and theory, between collecting trips and chromosome maps. But he was also living in a Soviet Union where science and politics were increasingly entangled. The chance to leave for the United States in 1927, on a Rockefeller Foundation fellowship, was both an escape and a leap into the unknown.

Theodosius Dobzhansky biography and the Birth of Modern Evolutionary Genetics

Crossing the Atlantic: Columbia University and the Drosophila school

Dobzhansky arrived in New York just after Christmas 1927, stepping into the legendary “fly room” at Columbia University. There he joined Thomas Hunt Morgan’s Drosophila group, a tight-knit team that had already shown how genes sit on chromosomes and how they can be mapped. In this cramped laboratory, jars of fruit flies lined the shelves like strange, living test tubes. For Dobzhansky, the experience was transformative. He saw that the same insects he had chased as a boy could, in the right setting, illuminate the deepest questions about how species change and how new ones emerge.

From Kiev classrooms to California labs: a turning point in the Theodosius Dobzhansky biography

When Morgan moved to the California Institute of Technology, Dobzhansky followed, trading East Coast winters for the light of Pasadena. There he began the blend of field and laboratory work that would define the Theodosius Dobzhansky biography as a story of evolutionary genetics in action. He and his colleagues trapped wild fruit flies in canyons and orchards, then brought them back to the lab to study their genes. The point was simple yet revolutionary: by measuring genetic variation in natural populations, one could watch evolution as an ongoing process, not just as history inferred from fossils.

At a time when some biologists doubted that small genetic changes in local populations could explain the large-scale patterns seen in palaeontology, Dobzhansky’s work argued the opposite. Microevolution in flies, he suggested, could indeed explain macroevolution over deep time. That bridge between scales would become one of his most enduring contributions.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Theodosius Dobzhansky

Genetics and the Origin of Species: a book that changed biology

In 1937, Dobzhansky gathered his ideas into a compact, deceptively modest book: Genetics and the Origin of Species. Written for biologists rather than mathematicians, it translated the new language of population genetics into concepts that naturalists and field workers could use. The book showed how mutation, natural selection, migration and genetic drift operate together in real populations, and how they can, over time, produce new species. It quickly became a cornerstone of the modern synthesis, the fusion of Mendelian genetics with Darwinian evolution that reshaped 20th-century biology.

Today, historians of science routinely treat this volume as a turning point in evolutionary thought. For anyone reading a serious Theodosius Dobzhansky biography, the book is one of the central characters: a slim work that opened the door to an entire research programme in evolutionary genetics. An online copy of the original 1937 edition is still available through Rockefeller University’s digital archive, giving modern readers a direct sense of how fresh and bold those ideas were when they first appeared.

Fruit flies and genetic diversity: evolution in real time

Beyond his books, Dobzhansky was best known among scientists for a long series of papers titled “Genetics of Natural Populations”. In them, he and his collaborators used fruit flies, especially Drosophila pseudoobscura, to measure how gene frequencies vary in the wild. They discovered that natural populations carry far more genetic diversity than many theorists had expected. Instead of a single, “best” version of a gene sweeping to fixation, many populations maintained a balance of different variants, a pattern known as balanced polymorphism.

This work turned the idea of a static species on its head. In Dobzhansky’s hands, a species became a dynamic swarm of changing gene frequencies, always in flux, always responding to environment and chance. That vision has permeated evolutionary genetics ever since, influencing everything from conservation biology to our understanding of how pathogens adapt to drugs.

“Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution”

In 1973, Dobzhansky published what may be the most quoted essay in biology, with the ringing title “Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution”. Written amid rising battles over creationism in American schools, the essay argued that evolution was the unifying principle that made sense of everything from fossils to embryology. Without evolution, he insisted, biology is just “a pile of sundry facts” – scattered observations without a narrative. With evolution, the facts form a coherent story about change, adaptation and common ancestry.

For many readers, this essay is their entry point into any Theodosius Dobzhansky biography. It shows him not as a narrow specialist but as a thinker concerned with the place of science in culture, with the way evolutionary ideas intersect with education, religion and democratic debate.

Taken together, Dobzhansky’s books and essays helped to establish evolutionary genetics as a central framework for modern biology, rather than a niche subfield.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Between field and lab: a hybrid way of doing science

Dobzhansky’s working style did not fit easily into simple categories. He was neither a pure theoretician nor a scientist who spent all his time in the lab. Instead, he built a career on moving back and forth between fieldwork and controlled experiments. He collected fruit flies in deserts, forests and orchards, then analysed their chromosomes under the microscope, hunting for inversions and other structural changes that might affect evolution.

That hybrid method made his work particularly compelling. Rather than rely solely on equations or on museum specimens, he tried to show how genetic processes played out in living, breathing populations. In doing so, he helped transform evolutionary biology from a largely historical discipline into something closer to a real-time science.

Collaborators, students and the making of a school

Dobzhansky was also a builder of scientific networks. At Columbia, Caltech and later Rockefeller University, he trained students who would become major figures in their own right, including population geneticists like Bruce Wallace and Richard Lewontin. His seminars were famously energetic, combining tough questions with humour and a willingness to speculate. Visitors recall evenings of loud debate, cigarettes and black coffee, where ideas about evolutionary genetics and human nature jostled with politics and philosophy.

This collaborative style helped turn the Theodosius Dobzhansky biography into more than a lone-genius story. His influence spread through a generation of evolutionary biologists who adopted his emphasis on genetic variation, on populations rather than idealised types, and on the value of bringing different methods together.

In short, his working life offers a template for how ambitious science can be both deeply technical and broadly human.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Race, genetics and the fight against pseudoscience

One of the most sensitive chapters in any Theodosius Dobzhansky biography concerns race. Writing in the shadow of Nazi atrocities and in the midst of segregation in the United States, he argued fiercely against the idea that “race” fixed a person’s destiny. In books such as Heredity, Race, and Society and Genetic Diversity and Human Equality, he tried to recast race not as a set of rigid types but as patterns of gene frequencies that blur into one another across populations. He maintained that the biological basis for ranking human groups in a hierarchy simply did not exist.

His stance invited both praise and criticism. Some activists felt he clung too tightly to the term “race” instead of abandoning it altogether. Others accused him of underestimating the social realities that genetic language could reinforce. Yet Dobzhansky’s central point – that genetic variation within groups is often greater than variation between them – has become a cornerstone of modern discussions about human diversity.

Debates over religion, evolution and “modern science”

Dobzhansky also found himself in the middle of arguments about whether a committed Christian could genuinely accept evolution. He described himself as a theistic evolutionist, seeing evolutionary processes as the means by which a creator brought the world into being. For some secular colleagues, this sounded like unnecessary compromise; for some religious leaders, it sounded like heresy. Yet he was adamant that accepting evolution did not mean abandoning moral or spiritual questions.

In essays and public lectures, he challenged both fundamentalists and scientific materialists who treated evolution as a weapon in a culture war. Instead, he cast it as a powerful, but limited, scientific framework for understanding life’s history – one that still left room for philosophical reflection.

Public reception: from specialist circles to the New York Times

Dobzhansky’s ideas sometimes spilled out of specialist journals into the broader press. A review by Harrison E. Salisbury in The New York Times of his book Heredity and the Future of Man highlighted his refusal to pin human worth on genetics alone, noting that he and other scientists could not even agree on how to define race. For Salisbury, this underscored a central message: that human beings are not locked into fixed biological castes, and that our cultural choices matter.

These controversies remind us that the Theodosius Dobzhansky biography is not just the story of technical advances. It is also about how scientific ideas circulate in society, and how they can be used – or misused – in arguments about identity and power.

Impact on Evolutionary Genetics and on Wider Society

Shaping the modern synthesis

Within evolutionary biology, Dobzhansky is often named alongside figures like Ronald Fisher, J.B.S. Haldane and Ernst Mayr as one of the architects of the modern synthesis. His particular contribution was to show, through data, how genetic mechanisms could produce the kinds of changes Darwin had only inferred. By measuring mutation rates, selection pressures and gene flow in real populations, he translated evolutionary theory into numbers and maps.

This work gave biologists a unified language for talking about adaptation and speciation. It made evolutionary genetics a central, organising discipline rather than a peripheral curiosity. Many modern textbooks, and indeed many current controversies over topics like climate-driven adaptation or antibiotic resistance, still lean on the concepts he helped popularise.

Influence on debates about human nature

Outside the lab, Dobzhansky’s insistence on the importance of genetic diversity fed into broader debates about human nature. He argued that the openness of human evolution – the fact that our species is genetically varied and culturally inventive – underpins both our creativity and our moral responsibility. In this sense, the Theodosius Dobzhansky biography belongs not only to the history of science but also to the history of political thought. His reflections on democracy, individuality and equality continue to surface in discussions about everything from personalised medicine to the ethics of genetic engineering.

His impact, then, is both technical and deeply cultural: he changed how scientists think about evolution, and he gave the wider public a new vocabulary for talking about human difference.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Faith, doubt and the human condition in the Theodosius Dobzhansky biography

Dobzhansky’s private beliefs were complex. Raised in the Eastern Orthodox tradition, he remained a communicant of the church even as he embraced evolutionary science. He saw no contradiction in this, arguing that evolution was simply the method by which creation unfolded. At the same time, he wrestled with questions about suffering, purpose and the limits of human knowledge, particularly in the wake of global wars and genocides.

This mixture of faith and doubt made him wary of simple slogans. He criticised both those who treated evolution as a new dogma and those who clung to literalist readings of scripture. For readers of a modern Theodosius Dobzhansky biography, this religious dimension is crucial: it helps explain why he invested so much energy in addressing teachers, clergy and lay audiences, not just fellow scientists.

Marriage, friendships and the emotional landscape of a scientist

In 1924, Dobzhansky married Natalia “Natasha” Sivertzeva, herself a geneticist. Their partnership was both personal and intellectual; they shared years of migration, laboratory moves and the challenges of building a scientific life in a new country. Friends recall a household filled with books, lively conversation and the occasional clash of strong personalities.

He also developed deep friendships with colleagues and students, including Francisco Ayala and others who would carry his ideas forward. These relationships gave his work a sense of continuity. When we read a Theodosius Dobzhansky biography today, we are often reading, indirectly, the memories of those who sat in his seminars or argued with him late into the night about genes, God and human destiny.

Seeing Dobzhansky as a husband, friend and mentor as well as a scientist rounds out the picture, reminding us that big theories are made by people with ordinary joys and sorrows.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Theodosius Dobzhansky

Illness, loss and a final burst of work

The last years of Dobzhansky’s life were marked by both grief and productivity. His wife Natasha died in 1969, a devastating loss. Around the same time, he was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and told he might have only a few years to live. Rather than withdrawing, he continued to write and lecture, taking up an emeritus position at the University of California, Davis, where he joined his former student Francisco Ayala.

It was during this period that he composed “Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution”, a late-career manifesto that distilled decades of thought into a few luminous pages. He worked almost to his final day, dying in 1975 in Davis, with his ashes later scattered in the Californian wilderness.

Remembering a life in science

After his death, colleagues produced biographical memoirs that captured both his scientific achievements and his idiosyncratic personality: the booming voice, the love of metaphor, the impatience with sloppy thinking. These tributes, alongside the growing historical literature on the modern synthesis, ensure that any serious Theodosius Dobzhansky biography today is built on rich sources rather than legend.

In these accounts, one sees a man who was unafraid of conflict, yet deeply committed to dialogue – a scientist who believed that understanding evolution was part of understanding what it means to be human.

The Lasting Legacy of the Theodosius Dobzhansky biography

A pioneer whose ideas still evolve

Half a century after his death, Dobzhansky’s influence is still visible across evolutionary genetics. Concepts he helped popularise – balanced polymorphism, the importance of genetic diversity, the integration of microevolution and macroevolution – now seem almost obvious. Yet they were not obvious when he began arguing for them. The very fact that students today can take these ideas for granted is part of the legacy charted in any Theodosius Dobzhansky biography.

At the same time, some of his views have been revised or challenged. New data from molecular biology, genomics and behavioural genetics have refined earlier models. This is as he would have wanted: science, for Dobzhansky, was a process, not a monument. What endures is not a fixed doctrine but a way of thinking about variation, change and the open-ended nature of human evolution.

Why his story matters now

In an era of gene editing, genomic surveillance and renewed arguments over evolution in schools, the questions that animated Dobzhansky have not gone away. How should societies talk about genetic differences without sliding into old prejudices? Can religious and scientific communities find common ground without diluting either faith or rigour? What does it mean to say that humans can, in some measure, “direct their evolution”?

By following the arc of the Theodosius Dobzhansky biography – from a beetle-collecting boy in the Russian Empire to a leading voice in American science – we gain more than a portrait of one man. We gain a lens on the 20th century’s struggles over knowledge, identity and power, and a set of tools for thinking about our own century’s dilemmas.

In the end, understanding the Theodosius Dobzhansky biography helps us understand something larger: how the story of evolution became a central story about who we are, where we came from and how we might choose to live together on a changing planet.

Frequently Asked Questions about Theodosius Dobzhansky biography

Q1: Who was Theodosius Dobzhansky and why is his biography important?

Q2: What is Dobzhansky best known for in evolutionary genetics?

Q3: What does the phrase “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution” mean?

Q4: How did Dobzhansky view the relationship between race, genetics and human equality?

Q5: Was Dobzhansky religious, and did that conflict with his science?

Q6: How does Dobzhansky’s work influence science and society today?