On an autumn morning in Leipzig in 2022, staff at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology threw their director into a pond. It was not a prank gone wrong but an improvised celebration: their boss, a soft-spoken Swedish geneticist who had spent decades coaxing fragments of DNA out of dusty bones, had just won the Nobel Prize. That splash in the courtyard is a fitting image for the Svante Pääbo biography: a life in which seemingly inert remains suddenly come alive, changing how we see ourselves and our place in history.

Over four decades, the Svante Pääbo biography traces the journey of a young medical student smuggling tissue samples out of a museum to a paleogenetics pioneer whose work revealed that living people carry genetic traces of Neanderthals and other extinct cousins. His research helped show that our species is not a neat, isolated branch of the tree of life, but the product of ancient entanglements, migrations and encounters written into our genomes.

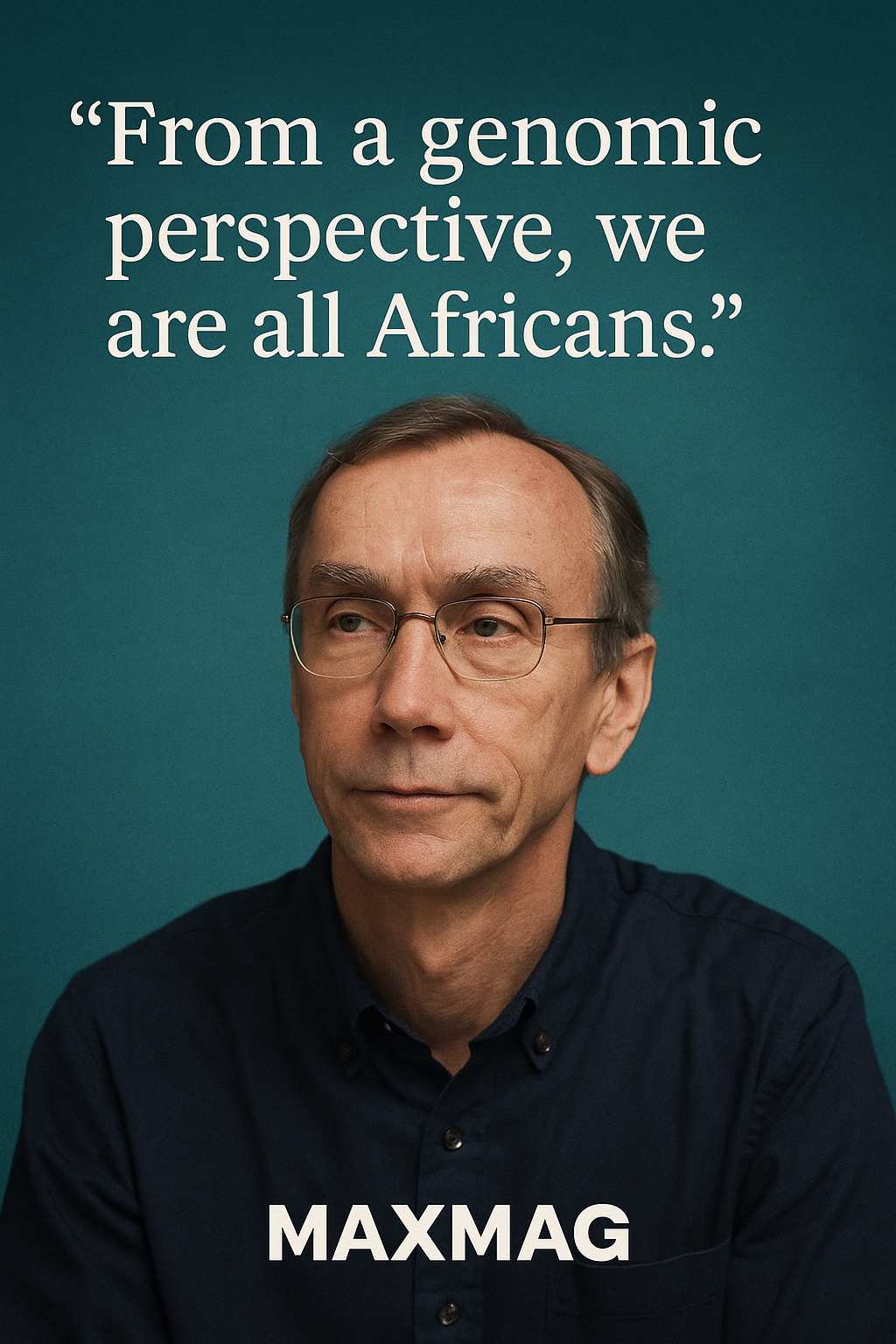

Svante Pääbo at a glance

- Who: Svante Pääbo, Swedish evolutionary geneticist and paleogenetics pioneer.

- Born: 20 April 1955, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Field and era: Ancient DNA research and human evolution, late 20th and early 21st century.

- Headline contributions: Sequencing Neanderthal DNA, discovering the Denisovans and showing that Neanderthal DNA persists in modern humans.

- Why he matters today: His work reshaped human evolution history, influencing medicine, archaeology and debates about what makes our species unique.

Early Life and Education of Svante Pääbo

A childhood between secrecy and science

The story behind the Svante Pääbo biography begins in post-war Stockholm, where he was raised by his mother, the Estonian-born chemist Karin Pääbo. She had fled Soviet occupation as a refugee, bringing with her a belief in education and perseverance. His father, biochemist Sune Bergström, was already on his own trajectory toward the Nobel Prize. But their relationship was complicated: Pääbo was the child of an extramarital affair, and his father visited his “second” family only occasionally and discreetly.

As a boy, Pääbo devoured adventure stories and archaeology books, imagining desert digs and ancient tombs. He was drawn to history as much as to biology, a tension that would later define his career. At home, chemistry and science were normal parts of conversation. Yet the family secret around his father’s double life also impressed on him how identity can be fragmented, how one person can belong to several worlds at once. It’s not hard to see echoes of this in his later fascination with hybrid human histories.

From Uppsala lectures to the first risky experiments

In the 1970s, Pääbo enrolled at Uppsala University, initially following a conventional path in medicine and molecular biology. He trained as a doctor, learned the language of enzymes and viruses, and wrote a PhD thesis on how an adenovirus protein helps the virus evade the immune system. Yet the lectures and lab courses did not quite quench his curiosity. The young student who had once dreamed of pyramids and mummies still felt the pull of history.

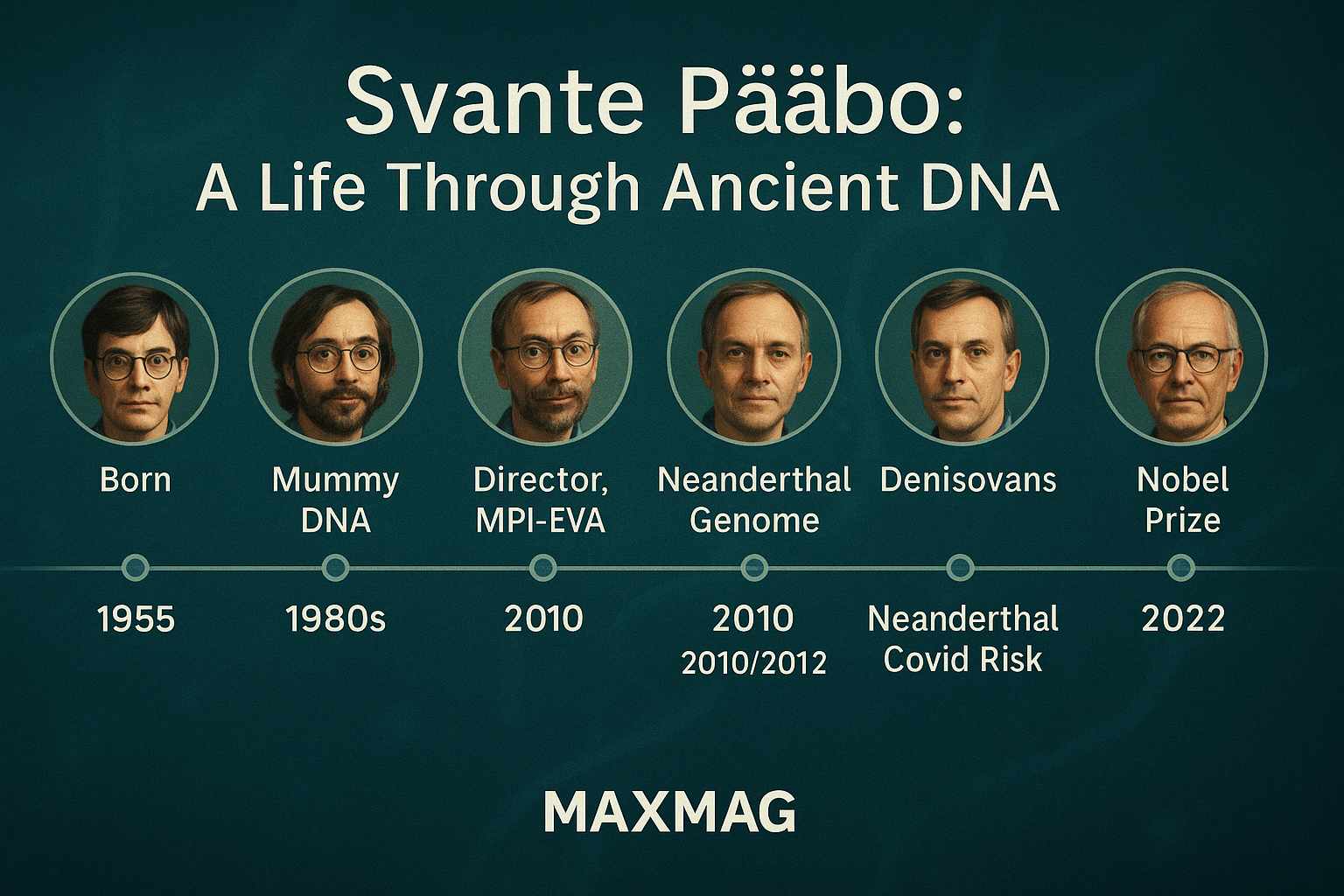

One day, that itch turned into action. Fascinated by Egyptian mummies, he began quietly collecting tiny tissue samples from museum specimens with the idea of looking for DNA. It was a technically audacious and professionally risky move: many senior scientists believed ancient DNA could not survive in usable form, and the field was rife with false claims. Over time, he managed to amplify genetic material from a 2,400-year-old mummy of a young boy, one of the first convincing demonstrations that ancient human DNA could be retrieved at all. That small experiment, done on the margins of his official work, hinted at a radically new way to study the past.

Svante Pääbo biography and the Birth of Paleogenetics

A risky experiment that would define the Svante Pääbo biography

In the mid-1980s, when Pääbo set out to find DNA in mummies and fossils, many colleagues saw ancient DNA research as a scientific sideshow. There were sensational claims about dinosaur DNA and other impossibilities, almost all of which collapsed under scrutiny. Against this backdrop, the Svante Pääbo biography stands out because he treated the challenge like a forensic investigation rather than a treasure hunt. He worried obsessively about contamination, repeated experiments, and insisted on independent confirmation.

When he moved through postdoctoral positions in Zurich and then at the University of California, Berkeley, under evolutionary biologist Allan Wilson, Pääbo began to crystallise the principles of what would become paleogenetics: ultra-clean labs, strict separation of modern and ancient samples, and a sceptical mindset that assumed contamination until proven otherwise. He was not just an evolutionary genetics pioneer; he was building the toolkit that would allow others to trust results in a field long seen as “kind of a joke”.

Neanderthals enter the story

The great turning point in the Svante Pääbo biography came with Neanderthals. These Ice Age relatives of ours had fascinated scientists for more than a century, but their bones seemed stubbornly silent about their genes. In the 1990s, Pääbo and colleagues managed to sequence fragments of mitochondrial DNA from a Neanderthal bone found in the Neander Valley in Germany. It was a tiny piece of the genome, but it showed that Neanderthals were genetically distinct from modern humans and chimpanzees.

That success proved that hominin DNA could survive for tens of thousands of years and be distinguished from the genetic noise of microbes and modern handlers. From there, the ambition grew: if fragments from a single mitochondrial genome were possible, why not aim for the entire nuclear genome of Neanderthals? It was an audacious proposal at a time when sequencing a single human genome still felt monumental and expensive. Yet this is where Pääbo’s mix of stubbornness and vision came to the fore.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Svante Pääbo

Sequencing the Neanderthal genome and beyond

In 2010, an international team based at the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, led by Pääbo, announced the first draft sequence of the Neanderthal nuclear genome. Using bone fragments from Neanderthals in Croatia and elsewhere, they pieced together billions of DNA letters and compared them with modern human and chimpanzee genomes. The work showed that people outside Africa carry roughly 1–2% Neanderthal DNA, the result of ancient interbreeding between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals tens of thousands of years ago. It was a landmark in the Neanderthal genome project and a central chapter in any Svante Pääbo biography.

For readers who want a technical overview of how that genome was assembled and analysed, the US National Human Genome Research Institute has archived a detailed report on the first complete Neanderthal genome sequence and its implications for human evolution. The paper rewrote human evolution history by making interbreeding, not isolation, central to our species story.

Discovering the Denisovans

If Neanderthal DNA made headlines, another discovery arguably had an even stranger flavour. In a Siberian cave called Denisova, archaeologists found a tiny bone fragment from a girl who lived around 50,000 years ago. When Pääbo’s team sequenced its DNA, they realised it did not match Neanderthals or modern humans. It represented a previously unknown lineage, now called the Denisovans. Suddenly the map of ancient human diversity became more crowded, with ghost populations whose traces survive mainly in genomes rather than in well-preserved skeletons.

Denisovan DNA turned up especially in people from parts of Asia and Oceania, contributing to traits such as adaptation to high altitude in Tibetans. This was paleogenomics functioning almost like time travel: from a single phalanx bone, the team reconstructed not just an individual but an entire population’s evolutionary story. For the Svante Pääbo biography, it underlined how ancient DNA research can reveal worlds that traditional archaeology barely hints at.

From Neanderthals to Covid-19 in the Svante Pääbo biography

Pääbo’s work did not stay confined to distant prehistory. In 2020, he and colleague Hugo Zeberg reported that a genetic risk factor for severe Covid-19 is linked to a Neanderthal-derived stretch of DNA on chromosome 3. People who carry that segment are more likely to need intensive care if infected with the coronavirus. In other words, a fragment of DNA inherited from an encounter between ancient humans and Neanderthals may still influence who gets sicker in a modern pandemic.

This line of work illustrates how the Svante Pääbo biography bridges evolutionary genetics and contemporary medicine. Paleogenetics is not only about reconstructing the past; it can help explain why some immune responses, metabolic traits or disease risks are distributed unevenly across today’s populations.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Clean rooms, contamination fears and patience

Anyone leafing through the Svante Pääbo biography quickly sees that his successes are rooted in methodical paranoia. Ancient DNA is fragile and easily swamped by modern contaminants: a few stray skin cells from a researcher, a flake of dust, a drop of saliva. In Leipzig, Pääbo’s lab developed elaborate clean-room procedures—full-body suits, filtered air, UV-irradiated surfaces—to minimise contamination. Samples are handled separately, lab personnel rotate between “dirty” and “clean” areas, and negative controls are built into every experiment.

This culture of caution spread globally as other groups entered ancient DNA research. Laboratories in Copenhagen, Boston and many other cities adopted similar protocols, turning paleogenetics into a mature discipline rather than a fringe curiosity. Pääbo’s insistence that surprising results be treated with scepticism until confirmed by independent labs helped build trust in a field prone to sensationalism.

Building a global network of collaborators

The Svante Pääbo biography is also a story of collaboration. Ancient DNA work is impossible without archaeologists willing to share rare bones and teeth, museum curators granting access to collections, and statisticians and computational biologists able to handle vast genomic datasets. From the 1990s onwards, Pääbo cultivated relationships with excavation teams around the world, from Croatia’s Vindija Cave to the Denisova Cave in Siberia.

At the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, where he has been director since 1997, he presided over an interdisciplinary environment that brought together linguists, primatologists, archaeologists and geneticists under one roof. This institutional context—part German research powerhouse, part intellectual crossroads—was crucial in turning ancient DNA research into a central pillar of human origins research.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Debates over what DNA can really tell us

Like any influential scientist, Pääbo has attracted criticism as well as accolades. Some archaeologists worry that the glamour of DNA risks overshadowing careful excavation and contextual interpretation. They fear that the Svante Pääbo biography, with its emphasis on genomes, might be read as implying that genetics alone can answer questions about culture, behaviour or identity.

Pääbo himself has often pushed back against this caricature, stressing that DNA is one line of evidence among many. Ancient genomes can reveal kinship patterns, population movements and episodes of mixing between groups, but they cannot tell us directly about language, ritual or meaning. His best work is most powerful when integrated with radiocarbon dates, artefact styles and environmental reconstructions rather than replacing them.

Misreadings of Neanderthal ancestry

Another recurring misconception concerns Neanderthal DNA in modern humans. After the Neanderthal genome results, headlines sometimes suggested that people with more Neanderthal ancestry might be more “primitive” or that population differences could be ranked along a ladder of progress. The scientific findings did nothing of the sort. Neanderthal contributions include variants that influence immunity, skin physiology and other traits, some helpful, some harmful in modern environments.

In interviews and in his book Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes, Pääbo has emphasised that the genetic distance between Neanderthals and modern humans is surprisingly small and that our uniqueness as a species likely lies in subtle regulatory changes, not in crude measures of “how Neanderthal” someone is. The more nuanced reading of the Svante Pääbo biography is not about hierarchy, but about entanglement: we are a composite species, shaped by many ancestors.

Why the Svante Pääbo biography Matters for Evolutionary Genetics and Wider Society

Redrawing the human family tree

Before Pääbo’s generation of ancient DNA work, many textbooks still portrayed human evolution as a relatively tidy succession: archaic species giving way to modern humans in a mostly linear fashion. The Svante Pääbo biography upended that picture. With Neanderthals, Denisovans and other archaic hominins all leaving genetic traces in different modern populations, the story looks less like a straight line and more like a braided river, with channels that separate, reconnect and sometimes vanish.

This has deep cultural resonance. It challenges myths of purity and singular origins, replacing them with an image of humanity as a network of exchanges. It suggests that what makes us “modern” was forged through contact, not isolation—a point that matters in contemporary debates about migration, identity and belonging.

From lab benches to newspaper front pages

When the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Pääbo in 2022 “for his discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution”, it was a recognition not just of technical feats but of a shift in perspective. The award sparked widespread media coverage, including a detailed Washington Post story on the scientist who deciphered the Neanderthal genome, which introduced his work to readers who might never open a specialist journal.

That public visibility matters. It brings evolutionary genetics into mainstream conversation and shows that questions about deep time—who we are, where we come from—are not just academic curiosities but part of our shared cultural landscape. In that sense, the Svante Pääbo biography is also a story about science communication and the power of narrative.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Family secrets and chosen families

The human side of the Svante Pääbo biography is as layered as his scientific work. For years, his father’s public silence about their relationship was a source of pain, even as Pääbo watched him receive his own Nobel Prize in 1982. Decades later, Pääbo would receive the same honour, creating a strangely symmetrical family history in which father and son, largely estranged in public, share the world’s most prestigious scientific award.

In his memoir, Pääbo writes candidly about his bisexuality and his early assumption that he was gay, before falling in love with American primatologist and geneticist Linda Vigilant. The couple have children together and have co-authored papers, blending personal and professional lives. Reading the Svante Pääbo biography as a family story, one sees not a lone genius in a tower but a man negotiating complex loyalties, identities and responsibilities.

What drives him?

Those who know Pääbo often describe him as both intense and playful: someone who can obsess over a lab protocol and then happily debate science fiction or politics over a beer. He has spoken about being driven partly by curiosity—wanting to know what is knowable about the past—and partly by a feeling of obligation to the dead, a sense that ancient individuals deserve to have their stories told as accurately as possible.

This mix of rigour and imagination is visible throughout the Svante Pääbo biography. He is not content with dry technical achievements; he wants those achievements to connect back to big, almost philosophical questions about consciousness, culture and what distinguishes Homo sapiens from other hominins.

Later Years and the Ongoing Chapter of Svante Pääbo biography

From director to elder statesman of paleogenetics

As he enters his seventies, Pääbo remains active in research but increasingly plays the role of elder statesman in paleogenetics. His Max Planck department continues to produce high-profile papers on ancient genomes—from Neanderthal families found in Siberian caves to the genetic history of early Europeans—while younger colleagues take on more of the day-to-day leadership.

Yet the Svante Pääbo biography is clearly not finished. New techniques, such as the recovery of ancient RNA and proteins, are beginning to complement DNA studies, opening fresh windows onto how extinct species functioned. Pääbo has been cautiously enthusiastic about these developments, reminding colleagues that each new molecule brings its own challenges of preservation and contamination.

Engaging with new ethical frontiers

In recent interviews, Pääbo has also reflected on the ethical limits of his field. He has expressed scepticism about the idea of “de-extincting” Neanderthals or other hominins, arguing that we lack the knowledge—and probably the moral framework—to bring back close human relatives as experimental subjects. Instead, he suggests, the responsible path is to keep learning from ancient DNA while respecting both the dead and the living communities connected to archaeological remains.

That stance positions the Svante Pääbo biography within broader discussions about genetics, consent and the treatment of ancestral remains—issues that will only grow more urgent as sequencing technologies become cheaper and more powerful.

The Lasting Legacy of Svante Pääbo biography

Changing how we think about what makes us human

Looking back, what makes the Svante Pääbo biography distinctive is not just a list of discoveries but a way of reframing humanity. Before his work, Neanderthals were often portrayed as crude foils to our supposed sophistication. Today, thanks in part to his research, they appear as close cousins with whom we shared genes, diseases and perhaps even stories around campfires.

His legacy extends beyond human evolution history into medicine and public imagination. Knowing that a slight tweak in a gene inherited from Neanderthals can influence Covid-19 severity, or that high-altitude adaptation in Tibetans may come from Denisovan DNA, reminds us that our bodies are time capsules. The Svante Pääbo biography teaches that the past is not behind us; it is inside us, in every cell.

Why this story matters now

In an era marked by polarisation and resurgent ideas of genetic “purity,” the Svante Pääbo biography offers a different narrative: one of mixture, entanglement and shared ancestry. It shows that science can undermine simplistic stories of “us” and “them” by revealing how much of “them” is in us, and vice versa.

Ultimately, understanding the Svante Pääbo biography helps us understand something larger about our world. It underscores that big scientific breakthroughs often come from people willing to cross boundaries—between fields, between countries, between past and present. And it suggests that humility, rigour and imagination are not just virtues in a lab; they are tools for living with the knowledge that we are, quite literally, the sum of countless ancestors whose voices we are only beginning to hear.

Frequently Asked Questions about Svante Pääbo biography

Q1: Who is Svante Pääbo and why is the Svante Pääbo biography important?

Q2: What was Pääbo’s biggest scientific breakthrough?

Q3: What are Denisovans, and how did Pääbo help discover them?

Q4: How does the Svante Pääbo biography connect ancient DNA to modern health?

Q5: Why did Svante Pääbo receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine?

Q6: What is the lasting legacy of the Svante Pääbo biography for science and society?