On a humid Gulf Coast morning in the 1930s, a boy in Alabama leaned so close to a fire-ant mound that it seemed to fill his entire world. Decades later that boy, Edward Osborne “E.O.” Wilson, would be hailed as “Darwin’s natural heir”, twice win the Pulitzer Prize and help invent the modern language of biodiversity. An honest E.O. Wilson biography is not just the story of a shy Southern child who loved insects; it is a map of how one mind tried to connect genes, societies and entire ecosystems into a single story about life on Earth.

This E.O. Wilson biography matters now because so many of the arguments he started are still with us. What do we owe the millions of species with whom we share the planet? How much of our behaviour is written in our genes, and how much is culture? Can the tools of biology really explain everything from ant trails to human wars? Wilson’s answers made him a pioneering evolutionary biologist, a lightning rod for controversy and, in his later years, one of the loudest voices calling for a global rethink of our relationship with nature.

Edward O. Wilson at a glance

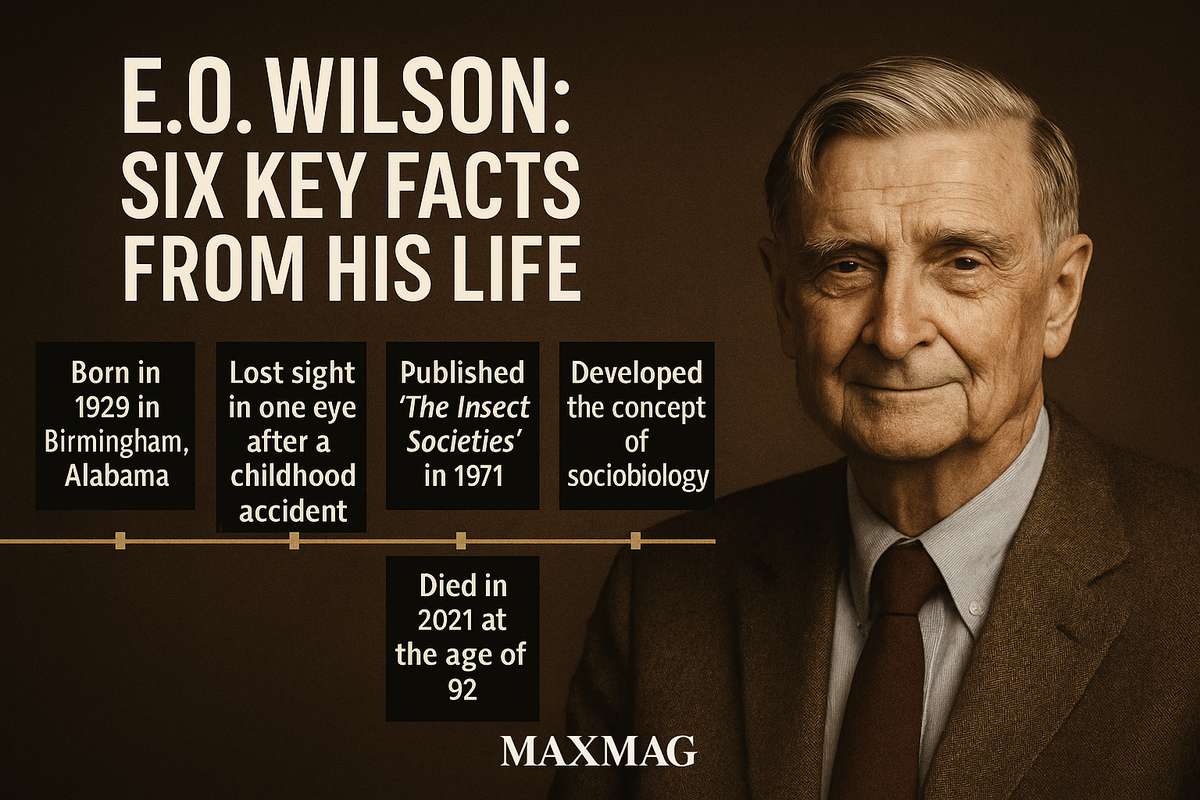

- Who he was: American biologist, myrmecologist and writer, born in 1929 in Birmingham, Alabama, and a central figure in 20th-century evolutionary biology.

- Field and era: From the post-war boom in ecology to the age of climate anxiety, he helped shape the history of sociobiology, island biogeography and conservation biology.

- Headline contributions: Ant biology, the theory of island biogeography, the controversial field of sociobiology, the biophilia hypothesis and the “Half-Earth” conservation proposal.

- Why he matters today: Any serious E.O. Wilson biography doubles as a guide to modern debates about biodiversity loss, human nature and the future of the planet.

Early Life and Education of E.O. Wilson

Southern childhood and a damaged eye

Edward Osborne Wilson was born on 10 June 1929 in Birmingham, Alabama, and grew up shuttling between towns in Alabama, Florida and the U.S. capital. His parents divorced when he was seven. That same year, a fishing accident left him blind in one eye; a spine from a fish hit his right pupil, which later had to be removed. With no depth perception but unusually sharp close-up vision in his remaining eye, he turned his attention to things that could be studied at arm’s length: ants, spiders, butterflies, anything that moved through grass and leaf litter.

In this sense, the E.O. Wilson biography begins as an accident of biology. The injury pushed him away from birds and large animals and into the miniature world where insects “run the world”, as he later liked to say. Instead of football fields, his playground became roadside ditches and vacant lots where he could squat for hours, notebook in hand, tracing the paths of ant columns.

From Eagle Scout to aspiring entomologist

As a teenager Wilson threw himself into scouting, earning the rank of Eagle Scout and serving as nature director at a Boy Scout summer camp. The badge work gave him a framework: collect, label, identify. Soon he began a formal survey of the ants of Alabama, corresponding with professional myrmecologists at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. That project led him in 1942 to one of his first scientific “finds”: the initial record of invasive fire ants established in the United States, near the port of Mobile.

It is easy, reading an E.O. Wilson biography in hindsight, to see destiny in these childhood obsessions. But at the time, he was simply a boy who found stability in a world of species labels and specimen jars. While his family life shifted around him, ants behaved predictably: they followed scent trails, defended their nests and raised their brood with mechanical dedication.

University of Alabama to Harvard

Money was tight, and Wilson worried that he would never afford college. Turned down for military service because of his eyesight, he enrolled instead at the University of Alabama, where he earned a B.Sc. in 1949 and an M.Sc. in 1950. His talent quickly became obvious, and with support from senior scientists he moved to Harvard for doctoral work. In 1955 he completed his PhD in biology and, that same year, married Irene Kelley, beginning a partnership that would last more than six decades.

A concise wrap-up of his early years might say this: the foundations of any E.O. Wilson biography are Southern landscapes, a damaged eye and an unfashionable passion for insects, all channelled through an education system that, almost by chance, opened the doors of Harvard to a young man from Alabama.

E.O. Wilson biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

How ants became the heart of the E.O. Wilson biography

Joining the Harvard faculty in 1956, Wilson began as an ant taxonomist, specialising in the painstaking work of describing new species and reconstructing their evolutionary relationships. To many colleagues, this looked like an obscure corner of zoology. Wilson saw something else: a way to use ant societies as a laboratory for understanding how evolution shapes cooperation, conflict and division of labour.

His field expeditions to Cuba, Mexico, the South Pacific and Melanesia produced hundreds of new species and an extraordinary mental library of social behaviours. Watching ants build nests, divide tasks and wage war, he began to ask a question that would define the E.O. Wilson biography as a sociobiology pioneer: if natural selection can build complex societies in insects, what might the same evolutionary logic say about birds, mammals and even humans?

Island biogeography and a new way of seeing ecosystems

In the 1960s Wilson teamed up with Princeton ecologist Robert MacArthur to tackle a different puzzle: why some islands are rich in species while others are poor. Rather than treating each island as a unique curiosity, they looked for general rules, balancing rates of colonisation and extinction. Their 1967 book, The Theory of Island Biogeography, proposed that the number of species on an island reflects a dynamic equilibrium shaped by island size and distance from the mainland, a conceptual leap that reshaped ecology and laid foundations for modern conservation biology history.

The model’s power lay in its simplicity. It invited conservation planners to see nature reserves, national parks and forest fragments as “islands” in a sea of human land use. A small reserve carved out of farmland might hold fewer species than a large, connected one. This insight would later feed directly into Wilson’s Half-Earth proposal and the broader E.O. Wilson legacy as a conservation strategist.

From insects to sociobiology pioneer

Wilson’s next leap was more controversial. In The Insect Societies (1971) he argued that the same evolutionary pressures that shape ant and bee colonies might also guide the behaviour of other animals. Four years later, in Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, he extended this logic to humans, suggesting that some aspects of our social life — aggression, altruism, even hierarchy — might have deep biological roots.

The E.O. Wilson biography of this period is the story of a scientist trying to construct a unified language for behaviour across species. To non-specialists, “sociobiology” can sound abstract, but the core idea is straightforward: evolution doesn’t stop at the neck. Just as natural selection shapes limbs and organs, it can also shape tendencies in social behaviour, nudging populations toward strategies that, on average, help genes survive in future generations.

Whether that insight was daring or dangerous would become the central debate of his career.

Key Works and Major Contributions of E.O. Wilson

Books that changed biology

Wilson’s bibliography reads like a tour of modern evolutionary thinking. After The Theory of Island Biogeography and Sociobiology, he turned to human culture in On Human Nature (1978), a book that explored how evolutionary pressures might interact with ethics, religion and politics. It won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction. In 1990, he and the German zoologist Bert Hölldobler published The Ants, an 800-page encyclopaedia of ant biology that also won a Pulitzer — a rare honour for a technical scientific work.

Other titles pushed his ideas into new territory. Biophilia (1984) introduced the notion that humans have an innate affinity for other forms of life, a concept that has become a staple in environmental psychology. Consilience: The Unity of Knowledge (1998) argued that the sciences, humanities and arts are ultimately connected by a set of shared principles — a consilience theory of knowledge that remains provocative in university debates. Late in life he wrote The Diversity of Life, The Future of Life and the autobiographical Naturalist, works that cemented the narrative side of the E.O. Wilson legacy.

From laboratory to global biodiversity debates

From the 1980s onwards, Wilson shifted from mainly laboratory and theoretical work toward global conservation. He was instrumental in framing biodiversity as a central scientific and moral issue, insisting that the accelerating loss of species was not just sad but dangerous, undermining the stability of ecosystems that support human societies. He helped inspire projects such as the Encyclopedia of Life and, later, the E.O. Wilson Biodiversity Foundation, which seek to document and protect the planet’s species.

For readers coming fresh to an E.O. Wilson biography today, these conservation ideas may feel familiar — we live in an age saturated with climate and extinction news. But when Wilson began writing about them, he was among a small group pushing biodiversity from a specialist concern to a mainstream topic.

Teaching, mentoring and public engagement

At Harvard, Wilson was known as a demanding but generous teacher. His lectures on ants, evolution and conservation drew not only biology students but also philosophers, writers and future policymakers. He encouraged students to develop their own field projects, pushing them to look closely at the “little things” in overlooked habitats — vacant lots, roadside verges, city parks.

Outside the classroom he wrote essays for general audiences and appeared in documentaries, sometimes with David Attenborough, to explain why ants and beetles matter as much as lions and whales. This public-facing work is part of the reason any modern E.O. Wilson biography feels less like a private academic story and more like a chapter in the broader history of biodiversity advocacy.

In short, his key works fuzzed the boundaries between research, philosophy and activism, making him not only an evolutionary biology pioneer but also a rare scientist who wrote as comfortably for Science as for readers in a suburban book club.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Field notebooks and “little things that run the world”

Wilson’s method combined old-fashioned natural history with modern mathematical thinking. He spent months in the field, knees in the mud, collecting specimens and filling notebooks with observations. Back in the lab, he worked with collaborators to turn those notes into models and theories, searching for patterns that would hold true beyond a single species or place.

His insistence on knowing organisms in detail — the way ant workers differ from soldiers, how queens found new colonies, when nuptial flights took place — gave his broader claims about sociobiology and biodiversity a grounding that critics, even when they disagreed, had to respect. In the E.O. Wilson biography as a working scientist, the microscope and the chalkboard were always in dialogue.

Collaboration across disciplines

Wilson’s most famous collaborations were with other scientists: Robert MacArthur on island biogeography, William Bossert on pheromones, Daniel Simberloff on experimental island ecology, Bert Hölldobler on ant societies. But he also worked with philosophers, theologians and writers, particularly in the Consilience years, to test whether his biology-first worldview could accommodate art, ethics and religion.

This willingness to talk across boundaries helped make him a consilience theory advocate at a time when many academics were retreating into narrower specialities. It is another thread that runs through any rich E.O. Wilson biography: the belief that the sciences and humanities are not enemies but potential partners in understanding human nature.

The section’s takeaway is simple: Wilson’s “secret” method was not a secret at all. It was curiosity plus collaboration, applied over many decades to questions that most people thought were either too small (ants) or too big (the fate of the planet) to tackle.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions in the E.O. Wilson biography

Why the E.O. Wilson biography of sociobiology sparked protests

When Sociobiology: The New Synthesis appeared in 1975, much of the biology community welcomed its sweeping synthesis. But the final chapter, which extended sociobiological thinking to humans, set off a political storm. Left-leaning critics, including some of Wilson’s own Harvard colleagues such as Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin, accused him of promoting biological determinism and providing cover for racism and sexism.

The conflict moved beyond academic journals. At a 1978 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, protesters rushed the stage and dumped a pitcher of water over Wilson’s head while chanting accusations. To many onlookers, the scene crystallised the fault line in late-20th-century science: could you talk honestly about the evolved roots of human behaviour without sliding into crude genetic explanations for complex social problems?

Wilson always insisted that his position was misread — that he believed culture and learning played vast roles, but that our species is not a blank slate. The best E.O. Wilson biography will acknowledge that, while sociobiology has evolved into fields like behavioural ecology and evolutionary psychology, the fears it provoked about misuse of biology in politics have not disappeared.

Debates over kin selection and multilevel selection

Late in life, Wilson courted fresh controversy by arguing that a central concept in evolutionary biology, “kin selection”, had been overstated as an explanation for altruism in animals. In a 2010 paper in Nature he and co-authors proposed that group-level selection — the idea that natural selection can act on groups as well as individuals — could better explain how complex societies evolve in some cases. This drew sharp criticism from Richard Dawkins and others who felt he was undermining decades of work in population genetics.

For non-specialists, this quarrel can seem esoteric, but it reveals something important about the E.O. Wilson biography as a scientist: he was willing to revise his views, even on topics that had helped make his name. To the end, he was arguing about the mechanics of evolution in the pages of top journals.

Support for flawed research and the question of legacy

After his death, historians examining Wilson’s correspondence found letters in which he defended psychologist J. Philippe Rushton, whose work on race and intelligence has been widely condemned as scientifically unsound and racist. Wilson’s advocacy included helping shepherd one of Rushton’s papers through peer review. Critics argue that this reflects a serious blind spot and sits uneasily alongside his public image as a champion of biodiversity and humanist ethics.

A fair E.O. Wilson biography needs to hold these pieces together: the visionary ecologist and writer, and the senior scientist whose judgement about colleagues could falter. His story illustrates how even celebrated figures in modern science can make troubling decisions, and why scientific communities must keep re-examining their heroes.

Impact on Biology and on Wider Society

Biodiversity as a public word

Wilson did not invent the term “biodiversity”, but he helped turn it into a household word. Through books, lectures and interviews, he argued that the web of life — from soil microbes to rainforests — underpins human wellbeing in ways we barely grasp. He compared species to rivets in an aeroplane wing: you can lose a few without catastrophe, but if you keep popping them out, eventually the structure fails.

His proposal that humanity should set aside roughly half the Earth’s land and sea area for nature, the “Half-Earth” idea, was deliberately bold. Critics said it was unrealistic or ignored the needs of people living in those regions. Wilson replied that it was meant as a guiding star, not a detailed zoning plan — a way to force conversations about how much of the planet we are willing to leave for other species.

An E.O. Wilson biography as environmental history

Seen against the backdrop of 20th- and early 21st-century science, the E.O. Wilson biography doubles as a history of environmentalism. He began his career in an era when many biologists focused on cataloguing species and describing their anatomy. He ended it in a world of international climate negotiations, mass-extinction warnings and global biodiversity targets, arguing that we were in danger of “impoverishing the world” if we allowed ecosystems to unravel.

For students, activists and policymakers, his books became bridges between technical research and public debate, helping translate dry data into stories that could influence parliaments and classrooms.

Influence on culture and ideas

Wilson’s notion of biophilia influenced architecture, urban planning and mental health research, lending scientific weight to the idea that humans thrive when they have daily contact with green spaces and other species. His work on sociobiology and evolutionary psychology seeped into popular discussions about parenting, gender and violence, sometimes in ways he might not have endorsed.

Through these channels, the E.O. Wilson legacy spread far beyond biology departments. He became a reference point in arguments about human nature, often invoked — sometimes fairly, sometimes not — as a symbol of the belief that biology matters in explaining our behaviour.

To get a sense of his broad public impact, one can read the memorial tribute in the Harvard Gazette, which describes how colleagues saw him as both a meticulous myrmecologist and a world-spanning thinker about conservation and culture.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Southern manners, global concerns

Colleagues often described Wilson as soft-spoken, unfailingly polite and personally modest. He carried a hint of Southern formality into Harvard lecture halls, preferring careful understatement to academic swagger. Yet behind the gentle manner was a steely willingness to defend ideas he thought important, whether about sociobiology, conservation or the future of universities.

The E.O. Wilson biography is full of anecdotes about his patience with students and his delight in field trips. Even late in life, he would kneel in the dirt with schoolchildren, helping them identify ants and spiders, insisting that science begins with simply noticing what lives under your feet.

Science, religion and humanism

On questions of faith, Wilson described himself as a kind of deist or scientific humanist. He had grown up in a Baptist environment but drifted from organised religion as a young man. Rather than denounce belief outright, he argued that religions are cultural products shaped by evolution, and he called for an “alliance” between science and faith communities to protect the natural world.

His 2006 book The Creation was framed as a letter to a Southern Baptist pastor, appealing to shared values in defence of biodiversity. This strand of the E.O. Wilson biography shows a man trying to bridge, rather than deepen, the divides between scientific and religious worldviews.

Family life and late-career routine

Wilson and his wife, Irene, were married for 66 years, raising a daughter, Catherine. Friends recall a disciplined daily routine: writing in the morning, meetings and students in the afternoon, reading in the evening. Even as honours piled up — the National Medal of Science, major international prizes, countless honorary degrees — he kept to a simple schedule built around work and family.

This constancy gives the E.O. Wilson biography an oddly domestic backdrop. The man whose ideas sparked global debates about human nature and biodiversity mostly lived in quiet New England suburbs, commuting to an office filled with books, specimens and, inevitably, ants preserved in alcohol.

Later Years and Final Chapter of E.O. Wilson

From emeritus professor to global elder statesman

Wilson formally retired from Harvard in the 199s but remained scientifically active for decades, publishing books, mentoring younger scientists and advising conservation projects around the world. He championed efforts to restore Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park, worked on plans for a new reserve in the Alabama delta near his childhood haunts and continued to refine the Half-Earth vision.

In these years, the E.O. Wilson biography reads less like that of a laboratory scientist and more like a roaming ambassador for biodiversity, flying from conferences to field sites to award ceremonies, always with a message about the urgency — and possibility — of protecting life on Earth.

Death and immediate reactions

Wilson died on 26 December 2021 in Burlington, Massachusetts, at the age of 92. Tributes poured in from scientists, conservationists and readers around the world. The National Geographic Society called him “one of the foremost naturalists in both science and literature”, while obituaries traced his path from Alabama boy to global figure.

A detailed National Geographic obituary underlined how his work on ants had grown into a broader campaign to place biodiversity at the centre of public life and policy. For many readers, that piece was their first encounter with an E.O. Wilson biography, arriving, poignantly, just as his voice left the stage.

His passing closed a chapter in 20th- and 21st-century science, but it did not resolve the debates he helped ignite. Those continue in classrooms, conservation meetings and online arguments about human nature.

The Lasting Legacy of E.O. Wilson biography

Science after Wilson

What, then, remains after we turn the last page of an E.O. Wilson biography? In science, his fingerprints are on multiple fields. Ecologists still use island-biogeography frameworks to design reserves. Behavioural scientists still argue about the balance between genes and culture. Conservation biologists still cite his warnings about mass extinction and his insistence that protecting half the planet is not a fantasy but a moral starting point.

Even when later data modify or overturn some of his specific claims — as happens to all scientific theories — the broader patterns he mapped out continue to guide research questions and conservation strategies.

Why his story matters beyond biology

Beyond science, the E.O. Wilson biography offers a model of how one person can move from a narrow speciality into questions of global ethics without abandoning rigour. He never stopped being, at heart, an ant man. But he refused to let that identity limit his ambition. Instead, he used what he learned from ants — about cooperation, conflict and interdependence — to think about cities, religions, economies and our obligations to future generations.

In an age of polarised debate, his attempt to build bridges between scientific humanism and religious traditions, between evolutionary biology and the humanities, remains instructive. You don’t have to agree with every part of the E.O. Wilson legacy to see the value of this bridge-building.

Understanding our world through the E.O. Wilson biography

Ultimately, understanding the E.O. Wilson biography means grappling with large questions: How much of human behaviour is shared with the rest of life? How many species are we willing to lose? Can scientific knowledge really be unified into a single story, or will it always be a patchwork of perspectives? Wilson’s answer was that we must at least try to weave the pieces together, because the stakes — for culture, for ethics, for the future of biodiversity — are too high to leave the connections unexplored.

That is why, long after his lifetime, the E.O. Wilson biography will remain required reading for anyone who wants to understand not just ants or evolutionary theory, but the wider drama of how modern science is reshaping our view of what it means to be human on a crowded, fragile planet.

Frequently Asked Questions about E.O. Wilson biography

Below are some common questions readers ask when they first encounter the life and work of E.O. Wilson, along with concise answers that highlight key themes of the E.O. Wilson biography.

Q1: Who was E.O. Wilson, in simple terms?

Q2: Why is the E.O. Wilson biography so closely linked to ants?

Q3: What is sociobiology, and why was it controversial in the E.O. Wilson biography?

Q4: How did E.O. Wilson influence modern conservation biology?

Q5: Did E.O. Wilson change his mind about any major scientific ideas?

Q6: What can readers today learn from the E.O. Wilson biography?