On a winter night in post-war Paris, a tall, intense scientist paced between benches at the Institut Pasteur, watching flasks of E. coli cloud and clear under different sugars. Those unremarkable bacteria were, for him, a stage on which one of the deepest dramas in biology was playing out: how cells decide which genes to switch on and off. The Jacques Monod biography is, at its heart, the story of how one French molecular biologist helped uncover that hidden logic – and then turned the same analytical gaze on politics, philosophy and the human condition itself.

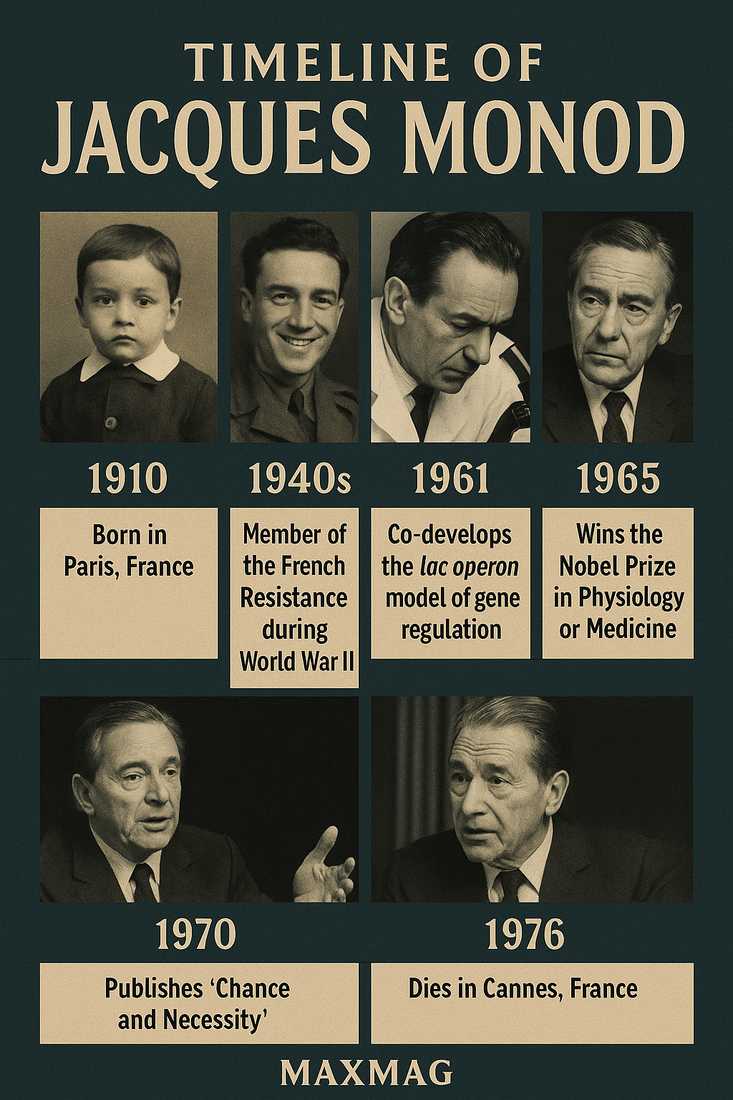

The Jacques Monod biography runs from comfortable bourgeois roots to wartime resistance, from painstaking experiments to a Nobel Prize, and from the fine structure of gene regulation to sweeping claims about the role of chance in the universe. He was a molecular biology pioneer who argued that life was the product of randomness filtered by necessity, yet he also believed that this stark view could be the basis for a new humanism. Understanding his life means tracing both the pipette work and the polemics, the petri dishes and the public debates.

Jacques Monod biography at a glance

- Who: Jacques Monod, French molecular biologist and biochemist.

- Field and era: Mid-20th-century science, especially the early history of molecular biology.

- Headline contributions: Co-creator of the operon model of gene regulation and Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine (1965).

- Why he matters today: His ideas on gene control, scientific freedom and the role of chance still shape how we think about biology and modern science.

Early Life and Education in the Jacques Monod biography

From Paris to the Sorbonne: first chapters in the Jacques Monod biography

Jacques Lucien Monod was born in Paris in 1910, into a cultivated, middle-class family that valued books as much as comfort. His father, a Frenchman who had lived in California, and his American mother created a bilingual, bicultural home that quietly primed him for an international outlook. The young Monod grew up in a city buzzing with art and ideas, but he was just as captivated by the quiet order of shells, stones and insects – early hints of a mind drawn to patterns in nature.

In his teens, the future molecular biology pioneer moved with his family to the south of France, to Cannes, where the sea and its teeming life seduced him into zoology. He began formal studies in the natural sciences at the Sorbonne, discovering that the discipline he loved was in the midst of transformation. The classical, descriptive biology of his early textbooks was giving way to a more quantitative, experimental approach. The Jacques Monod biography is inseparable from this broader shift: a generation trying to turn biology into a rigorous, almost physical science.

Apprenticeship in the laboratory and the birth of a researcher

As a young researcher, Monod learned the craft of experimentation in modest French laboratories, then in more modern facilities abroad. He spent time in Strasbourg and then in the United States, where he was exposed to cutting-edge work in genetics and biochemistry. Those experiences convinced him that the future of biology lay in understanding life at the molecular level – in the precise, mechanistic language already transforming physics and chemistry.

Returning to France, he joined the Institut Pasteur, an institution steeped in the traditions of microbiology and vaccines, but increasingly open to the new molecular biology. Here, in cramped labs filled with the smell of broth and disinfectant, he developed the careful, comparative style of experimentation that would later underpin his lac operon theory. The early chapters of the Jacques Monod biography are less about individual eureka moments than about a steady sharpening of questions: not just what cells do, but how they decide to do it – and when.

By the late 1930s, Monod had become a committed experimentalist with an increasingly clear sense of direction. The young biologist standing by his culture flasks was already asking the question that would define his life: how do living systems make choices?

Jacques Monod biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

The war years: resistance, risk and scientific interruption

The Second World War ripped through European lives, and the Jacques Monod biography is no exception. Mobilised in 1939, he soon joined the French Resistance, taking on the dangerous work of organising clandestine networks and coordinating communications. For a scientist who prized clarity and order, the chaos of occupation was a brutal lesson in contingency – the same notion of chance that would later appear at the heart of his philosophy.

During these years, his research was inevitably disrupted, but the experience sharpened his sense that science could not be separated from politics and ethics. The fight against fascism deepened his conviction that scientific honesty and intellectual freedom were non-negotiable. When he finally returned full-time to the laboratory after the war, he did so with the determination of someone who had seen how fragile civilisation could be, and how essential truth-telling was in any field, including biology.

From growth curves to the operon model of gene regulation

Back at the Institut Pasteur, Monod threw himself into the study of bacterial growth. On the surface, it might have looked like a narrow topic: how bacteria grow on different sugars. But buried in those growth curves was a puzzle about decision-making. When bacteria are offered two sugars, why do they consume one first and only later the other? This simple observation, known as diauxic growth, became a doorway into the molecular logic of gene control.

Working with colleagues like François Jacob, he developed the operon model of gene regulation. In essence, the lac operon theory suggested that a cluster of genes responsible for processing lactose could be turned on or off as a unit, controlled by a repressor protein and a stretch of DNA acting as a switch. For non-specialists, one way to picture it is to imagine a factory that can power up an entire production line only when the right raw material arrives. This was a turning point in the history of molecular biology: a concrete, testable way to understand how genes respond to the environment.

These ideas did not emerge in isolation. They were part of a wider movement to fuse genetics and biochemistry, and to see DNA, RNA and proteins as elements in a tightly choreographed system. The Jacques Monod biography cannot be separated from this broader effort to build a unified, mechanistic picture of life – a picture that would soon become standard in university curricula and classic NIH overviews of molecular biology and gene regulation.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Jacques Monod

The operon concept and a new language for molecular biology

The operon model quickly became one of the central concepts in molecular biology. It provided a vocabulary – promoters, operators, repressors – for talking about how genes are controlled. This framework helped transform a scattered collection of experiments into a coherent theory of gene regulation. Within a few years, the lac operon theory was in textbooks and lectures around the world, an anchor point for students trying to navigate the new terrain of DNA and RNA.

Monod’s work was not simply about naming parts. He insisted on connecting molecular mechanisms to functional questions: why would a bacterium bother to regulate a particular enzyme? The answer, he argued, lay in efficiency. Cells are like tight-fisted businesses, deploying expensive machinery only when it brings a return. In this sense, the Jacques Monod biography is a case study in how a scientist can link abstract molecular biology theory to everyday metaphors that make sense to non-experts.

Nobel recognition and the consolidation of a molecular biology pioneer

In 1965, Jacques Monod shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with François Jacob and André Lwoff, a formal recognition of their role in building the foundations of molecular genetics. By then, the operon model had become a symbol of the new discipline: clean, elegant and experimentally grounded. The award cemented his status as a leading molecular biology pioneer and placed his name alongside the biggest figures of 20th-century science.

The Nobel Prize also altered the trajectory of the Jacques Monod biography. Overnight, he became not just a researcher but a public figure, expected to comment on scientific policy, education and even the philosophy of biology. He took that role seriously, using his reputation to argue for research funding, open inquiry and a secular, rational view of the world. At the same time, he continued to publish technical work, never fully abandoning the bench for the podium.

His scientific papers, many co-authored with Jacob and others, mapped out an expanding landscape of regulatory circuits. They laid the groundwork for later discoveries in gene networks, development and cell signalling – fields that are now central to modern biomedicine and biotechnology.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Partnership with François Jacob and the Pasteur environment

One of the striking features of the Jacques Monod biography is how closely it is intertwined with that of François Jacob. The two men formed one of the legendary partnerships in 20th-century science, trading ideas in long, cigarette-smoke-filled conversations that ranged from experimental design to politics and literature. Their different temperaments – Monod the more austere and philosophical, Jacob the more narrative and reflective – complemented each other.

The Institut Pasteur itself played a crucial role. It was more than a workplace; it was a community that linked microbiologists, immunologists and geneticists in overlapping circles. Monod’s methods drew on this environment: he insisted on rigorous controls, quantitative measurements and relentless cross-checks. To younger colleagues, he could seem demanding, but also fiercely loyal when he believed in an idea. The Jacques Monod biography shows a scientist who saw collaboration not as optional but as the lifeblood of serious research.

A style that fused intuition and discipline

Monod’s working style combined flashes of intuition with methodical discipline. Colleagues recall him scribbling equations and sketches of regulatory loops on scraps of paper, then insisting that every model be pinned down by hard data. In this, he anticipated the systems-biology perspective that treats cells as dynamic networks rather than collections of isolated genes.

For non-experts, one way to picture his approach is to imagine a composer who hears a symphony in his head but then sits down to painstakingly score every instrument. The Jacques Monod biography is full of such moments where a hunch becomes a hypothesis, and then a carefully orchestrated experiment.

This mix of imagination and rigour helped define what many now think of as the “Pasteur style” of research: bold in ideas, conservative in evidence, and deeply aware of the stakes for medicine and society.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

“Chance and Necessity” and the philosophical storm

In 1970, Monod published Chance and Necessity, a book that attempted to extract a philosophy of life from the lessons of molecular biology. He argued that randomness at the level of mutations, combined with the necessities imposed by natural selection, could explain the complexity of living beings without recourse to purpose or design. For many readers, this was a startlingly stark vision of the universe.

The book transformed the Jacques Monod biography from the story of a laboratory scientist into that of a public intellectual. It also drew heavy criticism, not only from religious thinkers but from some historians and philosophers of science who felt he overstated the reach of his ideas. Debates about the Chance and Necessity thesis reached the pages of major newspapers and magazines, including long essays in outlets like the science section of The New York Times, where the implications of modern biology for human meaning were fiercely contested.

Misunderstandings about determinism in the Jacques Monod biography

A common misconception is that the Jacques Monod biography describes a man who believed everything was predetermined and that human freedom was an illusion. In fact, his emphasis on chance was meant precisely to carve out a space for genuine novelty in nature. If mutations are random, and if history is shaped by contingent events, then the future is not written in advance.

Monod did argue that there is no external purpose guiding evolution, but he also believed that humans, as conscious beings, could create their own values. His critics sometimes caricatured him as a cold determinist, but a closer reading of his work shows a complicated, often uneasy attempt to reconcile a scientific worldview with ethical commitment. The Jacques Monod biography is better understood not as a manifesto for nihilism but as an invitation to rethink what responsibility means in a universe without guarantees.

These controversies highlight one of his enduring legacies: the insistence that scientists cannot retreat from philosophical and political questions, even when their answers are uncomfortable.

Impact on Molecular Biology and on Wider Society

From gene regulation to biotechnology and medicine

The technical contributions traced in the Jacques Monod biography ripple through today’s laboratories and clinics. The operon model of gene regulation became a template for understanding how cells control everything from metabolism to development. Variations on this theme underpin our grasp of antibiotic resistance, cancer pathways and the design of synthetic gene circuits.

For example, modern biotech companies routinely engineer bacteria and yeast to produce drugs, enzymes and materials. These engineered systems rely on regulatory switches not so different from the lac operon theory that Monod helped develop. When a company designs a microbe that turns on a therapeutic protein only in response to a specific signal, it is, in a real sense, extending the logic first worked out in those Pasteur flasks.

A model for scientific citizenship in 20th-century science

Beyond the lab, Monod’s career offers a model of what it means to be a scientific citizen. He spoke out on issues ranging from nuclear disarmament to academic freedom, drawing on his wartime resistance experience and his sense of moral obligation. The Jacques Monod biography thus sits at the crossroads of molecular biology and civic life, showing how a researcher can use scientific authority without abandoning self-criticism.

In a period when public trust in science is often contested, his insistence on clarity, honesty and the willingness to say “I don’t know” feels particularly relevant. His legacy reminds us that the methods of the lab – scepticism, openness to evidence, and transparent debate – can also serve as political virtues.

Taken together, his scientific and social impacts mark him as one of the defining figures in the history of molecular biology and modern intellectual life.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

An austere humanist with musical tastes

The man who appears in the Jacques Monod biography was not only a Nobel laureate, but also a musician, reader and committed humanist. He was an accomplished cellist, and chamber music offered him both solace and structure. Friends recall evenings where he moved almost seamlessly from discussing gene regulation to debating Mahler or Bach.

Philosophically, he was a secular humanist, convinced that ethics must be built without recourse to supernatural authority. This did not make him indifferent to suffering; on the contrary, his wartime experiences and his reading in existential philosophy left him acutely aware of human vulnerability. The Jacques Monod biography shows someone who tried to live in accordance with his principles, even when that meant taking unpopular stands.

Family life and the strains of ambition

Like many high-achieving scientists, Monod wrestled with the tension between professional ambition and family responsibilities. His long hours at the Institut Pasteur and his growing role in international scientific bodies inevitably took a toll on his private life. Accounts from those close to him describe a man who could be absorbed, even distant, when wrestling with a difficult problem, yet attentive and generous in quieter moments.

These complexities give the Jacques Monod biography a human texture. He was neither a saint nor a villain, but a person trying to balance competing demands: curiosity and care, solitude and solidarity, the pull of the lab and the claims of those he loved.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Jacques Monod

Leadership at the Institut Pasteur and final research efforts

In his later years, Monod served as director of the Institut Pasteur, steering the historic institution through a period of change. He championed basic research, arguing that practical advances in medicine depended on a deep understanding of fundamental processes. The administrative burdens were heavy, but he approached them with the same intensity he had once devoted to his flasks of bacteria.

Even as he took on leadership roles, he kept a close eye on new developments, including the rise of recombinant DNA techniques and early biotechnology. The final chapters of the Jacques Monod biography show a scientist who, while rooted in the first generation of molecular biology, remained open to the new tools and questions of post-war biology.

Illness, reflection and the closing of a life

Illness eventually forced him to slow down, but even then, he remained engaged with the philosophical and ethical questions raised by modern biology. He continued to write and to give interviews, defending both the autonomy of science and the need for scientists to speak plainly about uncertainty. As his health declined, he became more reflective, but not less convinced that chance and necessity offered the most honest description of life’s unfolding.

When he died in the 1970s, obituaries around the world emphasised not only his Nobel Prize but his broader role in shaping the culture of science. The Jacques Monod biography thus closes not with a single final discovery, but with a body of work – experimental, institutional and philosophical – that continued to influence laboratories and lecture halls long after his death.

The Lasting Legacy of Jacques Monod biography

From textbooks to debates about human meaning

Today, students encounter Monod’s ideas early in their training: in diagrams of the lac operon, in discussions of gene regulation, and in histories of molecular biology that trace how DNA went from a mysterious chemical to the central concept of the life sciences. The Jacques Monod biography is woven into these stories as a key thread, one that ties together experiments, institutions and philosophical arguments.

But his influence goes beyond the classroom. Debates about evolution, randomness and purpose still draw, knowingly or not, on the framework he proposed in Chance and Necessity. When contemporary thinkers argue about whether life has a built-in direction or whether we are the products of blind processes, they are, in effect, revisiting questions that Monod helped pose in the language of 20th-century science.

Why the Jacques Monod biography still matters

In an era of gene editing, personalised medicine and synthetic biology, the issues raised in the Jacques Monod biography feel newly urgent. How do we balance the power to manipulate life with humility about what we do not yet understand? How do we talk honestly about chance and risk without paralysing ourselves with fear? Monod’s insistence on lucidity – on seeing the world as it is, not as we wish it to be – remains a valuable guide.

Ultimately, the enduring appeal of the Jacques Monod biography lies in its combination of intellectual ambition and moral seriousness. He treated biology not as a narrow technical field, but as a window onto human existence. To study his life and work is to confront, again, the unsettling but liberating possibility that meaning is something we create together, in full awareness of the chance events that brought us here.

Frequently Asked Questions about Jacques Monod biography

Q1: Who was Jacques Monod and why is his biography important in molecular biology?

Q2: What is the operon model that features in the Jacques Monod biography?

Q3: Why did Jacques Monod write “Chance and Necessity” and what was controversial about it?

Q4: How did Jacques Monod’s wartime experiences shape his scientific career?

Q5: What is Jacques Monod’s legacy for today’s biologists and students?

Q6: Is Jacques Monod’s emphasis on chance compatible with human freedom and values?