In the long, careful history of laboratory science, the story that sits at the heart of any serious Kary Mullis biography sounds almost like fiction. A chemist driving along a dark California highway in 1983 has a sudden idea about copying DNA, an idea so simple and so powerful that it will split biology into “before” and “after” PCR.

By the time he died in 2019, Kary Banks Mullis had become one of the most celebrated and contentious figures in modern molecular biology. Nobel laureate, PCR pioneer, surfer, LSD experimenter, climate and HIV/AIDS contrarian – a Kary Mullis biography is as much about a rebellious personality as it is about the invention that allowed scientists to amplify a single fragment of DNA into billions of copies in a few hours.

At a Glance: Kary Mullis

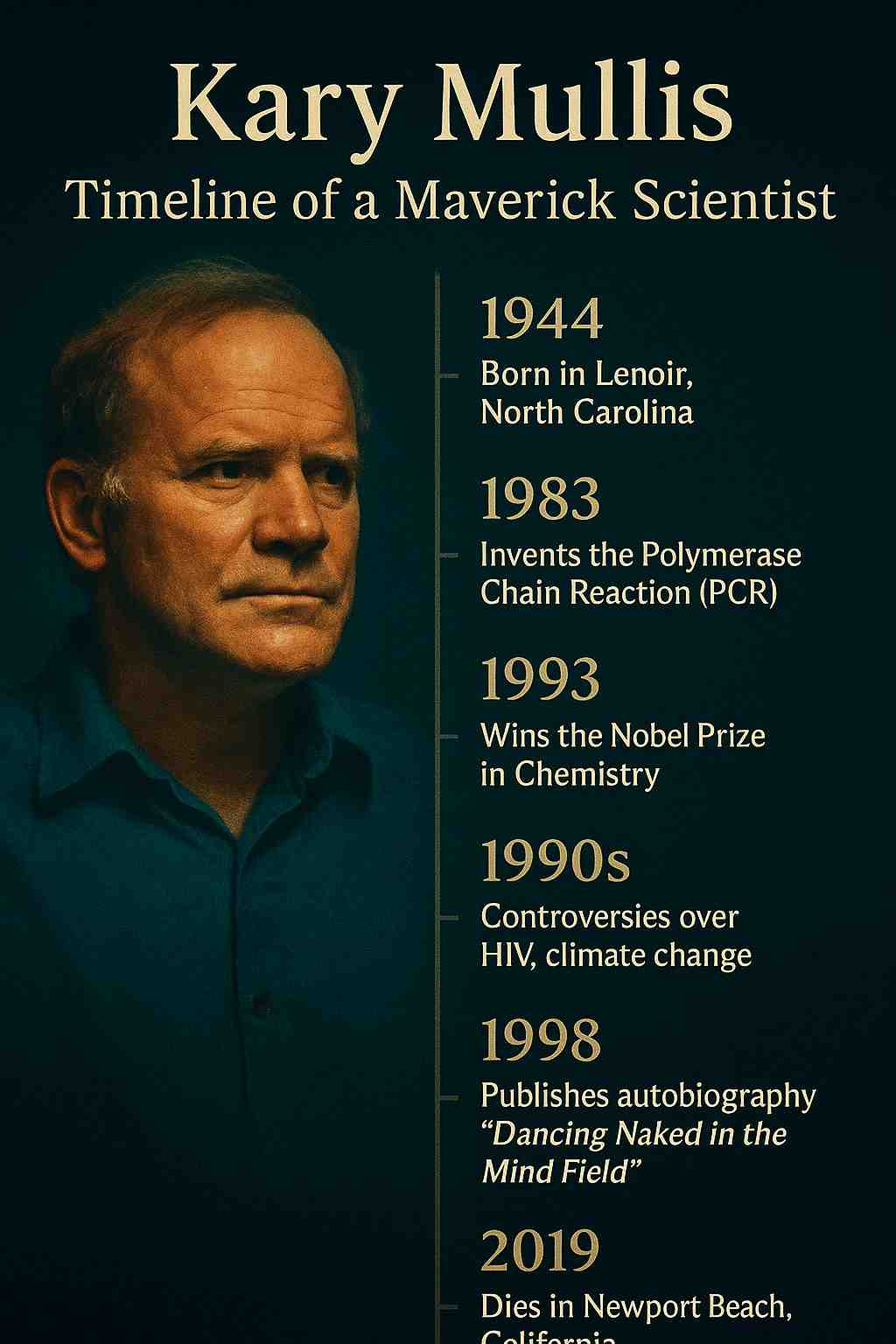

- Who: Kary Banks Mullis (1944–2019), American biochemist and molecular biology pioneer.

- Field & era: Biochemistry and DNA technology during the late 20th century’s biotechnology revolution.

- Headline contribution: Invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a method to amplify DNA billions of times.

- Why he matters today: PCR underpins everything from COVID-19 tests to forensic DNA profiling, while the Kary Mullis biography illuminates how one disruptive mind can reshape modern science – for better and sometimes for worse.

Early Life and Education of Kary Mullis

Growing up curious in the American South

Kary Banks Mullis was born on 28 December 1944 in Lenoir, North Carolina, near the Blue Ridge Mountains, and grew up in a family with farming roots. As a child he prowled basements and fields, fascinated by spiders, improvised experiments and the small ecosystems of rural life. Those early years, recalled later in his memoir, gave the Kary Mullis biography its first theme: a boy who preferred tinkering and testing things to simply accepting what adults told him.

From Georgia Tech to Berkeley: foundations of a Kary Mullis biography

After high school in Columbia, South Carolina, Mullis studied chemistry at the Georgia Institute of Technology, graduating in 1966. He flirted with chemical engineering and astrophysics, but chemistry’s mix of hands-on experiment and abstract theory won out. In the late 1960s he moved west to the University of California, Berkeley, for a PhD in biochemistry, immersing himself in the ferment of California’s science and counterculture.

Berkeley in that era was a crucible for both 20th century science and radical politics. Mullis later described learning as much from psychedelic trips and late-night conversations as from formal lectures. The future Nobel laureate was already a creature of two worlds: the rigorous, quantitative universe of nucleic acids, and a freewheeling personal life that would colour every chapter of this Kary Mullis biography.

Detours: fiction, bakeries and postdoctoral wanderings

After completing his doctorate, Mullis did not march straight into a conventional academic career. He took a postdoctoral fellowship in pediatric cardiology at the University of Kansas Medical School, then another in pharmaceutical chemistry at UC San Francisco. But he also veered off course, managing a bakery, writing science fiction and wondering whether he truly wanted a life of grant applications and tenure committees.

Those detours mattered. They meant that when he finally landed a job at a young biotechnology company, Cetus Corporation in Emeryville, California, he arrived not as a polished molecular biology insider but as an outsider: a skilled chemist who believed rules were optional and who saw the laboratory as another playground for bold ideas.

Kary Mullis Biography and the Birth of PCR

The highway revelation that defines the Kary Mullis biography

The central scene of any Kary Mullis biography takes place on a twisting Mendocino County road in 1983. Driving with his then-girlfriend, also a Cetus chemist, Mullis began to wonder if a pair of short DNA sequences – primers – could be used to mark the start and end of a target region in the genome. If a DNA polymerase could copy between those primers repeatedly, each cycle would double the amount of that specific DNA stretch.

What he imagined was an exponential copying machine: heat to separate the DNA strands, cool to let primers stick, extend with polymerase, then repeat. Each round would create more templates for the next; after 20 or 30 cycles, you could obtain billions of copies from an almost invisible starting sample. In the history of polymerase chain reaction, that was the conceptual leap, and it came not in a lecture hall but behind the wheel of a Honda.

From idea to experiment: skepticism in the lab

Back at Cetus, Mullis pushed to test his idea. The early experiments were messy. He used conventional DNA polymerases that fell apart at high temperatures, forcing the team to add fresh enzyme each cycle. Colleagues worried about controls, contamination and reproducibility. It was the kind of situation where many eccentric ideas quietly die.

But Mullis’s supervisor, Thomas White, recognised the potential and reassigned him to focus on the polymerase chain reaction full-time. Other scientists at Cetus, including Randall Saiki and Henry Erlich, were brought in as “top-notch experimentalists” to make the method work on a medically important target: the β-globin gene associated with sickle-cell disease. Their results, published in 1985, helped convince a skeptical community that PCR could transform molecular biology, even if it also complicated the question of how much credit any Kary Mullis biography should give to the inventor versus the team.

Taq polymerase and the leap to a biotechnology revolution

The real revolution came when Saiki and others introduced a heat-stable polymerase from the thermophilic bacterium Thermus aquaticus, known as Taq. Because Taq could survive the high temperatures used to separate DNA strands, the enzyme only needed to be added once at the start of a reaction. Suddenly PCR was cheaper, faster and easily automated – ready to power the biotechnology revolution, forensic DNA testing and, decades later, COVID-19 diagnostics.

In 1993, Mullis shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this work, and PCR quickly became the textbook example of how a simple conceptual breakthrough can reshape an entire field of 20th century science. Any serious Kary Mullis biography must hold those two realities together: PCR was both a team effort in a corporate lab and the product of one chemist’s audacious imagination.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Kary Mullis

From sickle-cell diagnosis to DNA forensics

The early scientific papers on PCR focused on diagnostics. By amplifying β-globin sequences, researchers could detect DNA signatures of sickle-cell anemia in patient samples with unprecedented sensitivity. Very quickly, other labs adapted PCR to track viral infections, identify genetic mutations and identify individuals through their DNA profiles. The technique became a cornerstone of forensic science, helping to solve crimes and exonerate the innocent by providing extremely precise genetic fingerprints.

In many ways, this is where a Kary Mullis biography intersects with public life. By making DNA evidence practical, PCR contributed to a broader conversation about justice, privacy and the power of biotechnology pioneer tools to change lives well beyond the lab.

Scientific writing and the story of PCR

Mullis was not just a bench scientist; he was also a storyteller. His Scientific American article “The Unusual Origin of the Polymerase Chain Reaction” and his book Dancing Naked in the Mind Field offered a highly personal version of polymerase chain reaction history – one in which a lone genius, fuelled by intuition and occasional LSD, rewrites the rules of biology.

Journalists and fellow scientists have since pointed out that this narrative smooths over the contributions of colleagues and understates how much refinement and engineering it took to turn the initial insight into a robust technology. Still, those writings are a crucial source for any Kary Mullis biography, revealing how the Nobel laureate wanted his own story told.

Beyond PCR: Altermune and “programmable immunity”

In later years, Mullis turned to immunology and entrepreneurship. With Altermune, a start-up he founded, he pursued the idea of “programmable immunity”: using specially designed nucleic acids called aptamers to redirect the body’s existing antibodies toward dangerous bacteria and other threats. A University of Texas news release described Altermune’s work in an Austin bioscience incubator, casting Mullis once again as an innovator pushing molecular diagnostics and therapeutics in new directions.

While these projects never rivalled PCR in impact, they show a restless mind unwilling to be defined solely by one invention, even one that had already revolutionised molecular biology.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

A chemist in a biologist’s world

Mullis often described himself primarily as a chemist, even as he worked in what most outsiders would label molecular biology. That outsider stance shaped his methods. He liked simple experimental setups, clear conceptual pictures and bold shortcuts, rather than the cautious incrementalism that marks much mainstream research. At Cetus he ran the DNA synthesis lab but was known as much for his improvisation as for his meticulousness.

This dual identity – both within the field and slightly apart from it – is critical to understanding the working style that runs through any Kary Mullis biography. It allowed him to see the polymerase chain reaction as a basic chemical process that could be tamed, but it also made other scientists uneasy about his disregard for standard protocols.

Collaboration and conflict at Cetus

Accounts from former colleagues paint a picture of an inventive but volatile co-worker. Mullis could be charming and funny, but he was also capable of fierce arguments and dramatic gestures. California Magazine later chronicled episodes that ranged from public disputes with partners to near-physical confrontations at staff gatherings.

Yet he also inspired loyalty. Thomas White stuck by him when others wanted him removed from projects, and multiple colleagues recognised that without Mullis’s conceptual leap and stubborn insistence on testing it, PCR might never have emerged in the form it did. The Kary Mullis biography is thus a case study in how difficult personalities and breakthrough ideas often travel together in the history of science.

Intuition, risk and the PCR pioneer mindset

Mullis’s own description of discovery was intensely intuitive. He credited daydreaming, surfing and chemically altered states with helping him see patterns that more conventional minds might miss. In his view, a good scientist was not merely a careful experimenter but a person willing to bet on unorthodox ideas. That attitude drove his PCR pioneer status – and later, as we shall see, led him into areas where intuition collided with hard evidence.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

The HIV/AIDS denial that shadows the Kary Mullis biography

No honest Kary Mullis biography can avoid his role in HIV/AIDS denialism. Despite having no research record in virology or epidemiology, Mullis repeatedly questioned the strong scientific consensus that HIV causes AIDS. He argued that he could not find a single paper definitively proving the link, a claim that has been thoroughly refuted by decades of research and clinical data. To understand the established view, readers can consult resources from major institutions such as the U.S. National Institutes of Health on HIV and its treatment.

Major medical institutions and public health agencies worldwide agree that HIV is the cause of AIDS, a conclusion supported by multiple lines of evidence: the isolation of the virus, its transmission patterns, the correlation between viral load and disease progression, and the dramatic effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy in reducing illness and death. Mullis’s public statements on this issue have been widely criticised by infectious disease experts and fact-checkers.

Climate change, ozone and “Nobel disease”

Mullis was equally skeptical about human-driven climate change and the scientific understanding of ozone depletion. In his view, global warming and the ozone hole were products of bureaucratic politics and groupthink rather than careful data. Science writers and skeptics have since pointed to him as an example of “Nobel disease” – the tendency of some laureates to adopt fringe positions outside their speciality, sometimes trading on their fame to promote ideas that experts in those fields reject.

For readers trying to make sense of the Kary Mullis biography, the key distinction is this: his brilliance in devising PCR does not automatically translate into authority on every scientific question, especially those in disciplines he never studied or worked in.

Myths about PCR and what Mullis actually claimed

In recent years, Mullis’s comments about PCR have been widely misused in debates about viral testing, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some activists have cherry-picked his remarks to claim that PCR “cannot” diagnose infection, ignoring the way the technique is used in combination with clinical judgment, viral culture and other tests. Molecular biology experts and science communicators have stressed that PCR is in fact a cornerstone of reliable diagnostics when properly calibrated, a view echoed in detailed reporting on PCR’s role as the COVID-19 “gold standard” test.

The nuance often lost in online arguments – and restored in a careful Kary Mullis biography – is that Mullis’s skepticism focused on how some people interpreted viral load numbers, not on the basic chemistry of PCR itself. The method remains rock-solid when used as intended.

Impact on Molecular Biology and on Wider Society

Rewriting the toolkit of modern science

Before PCR, amplifying a specific segment of DNA was slow, laborious and often impossible from tiny samples. After PCR, researchers in genetics, ecology, cancer biology and countless other fields gained the ability to copy any chosen fragment quickly and cheaply. The Nobel Committee itself has emphasised that Mullis’s invention made it possible to study genomes in detail and underpins everything from gene mapping to evolutionary studies.

In everyday terms, PCR is like giving scientists a photocopier for DNA. That “photocopier” now sits at the heart of projects ranging from the Human Genome Project to microbiome surveys – a reach that any Kary Mullis biography must treat as central.

Forensics, justice and the public imagination

PCR also changed the world outside the lab. By amplifying DNA from hair, blood or other trace evidence, forensic scientists could match suspects to crime scenes with extraordinary accuracy or clear people who had been wrongly convicted. Essays in legal and scientific outlets have described how DNA evidence, powered by PCR, contributed to hundreds of exonerations and reshaped public expectations of what “proof” looks like in court.

This side of the Kary Mullis biography speaks to his broader legacy: a technology that has saved lives by correcting miscarriages of justice, even as the inventor himself remained a chaotic and sometimes troubling public figure.

Pandemics and the gold standard PCR test

When SARS-CoV-2 emerged in 2019, PCR was quickly adapted to detect its genetic material in nasal swabs. Within months, laboratories worldwide were using polymerase chain reaction history and know-how to scale up COVID-19 testing. In-depth journalism has framed PCR as the “gold standard” for diagnosing the virus, underscoring how a 1980s idea became central to 21st century public health.

Mullis himself did not live to see this chapter – he died just months before the pandemic – but any modern Kary Mullis biography must acknowledge that the technique he conceived became one of the key tools for managing a global crisis.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Surfer, storyteller, provocateur

Away from the lab bench, Mullis cultivated a deliberately unconventional persona. He surfed, played guitar, told wild stories about fluorescent raccoons and paranormal encounters, and spoke openly about synthesising and taking LSD during his student days. Friends described him as funny, restless and brilliant; critics saw a man addicted to controversy.

These contrasts give the Kary Mullis biography much of its narrative tension. He did not fit the stereotype of the lab-bound introvert. Instead, he insisted that curiosity, risk-taking and a willingness to break taboos – scientific and social – were essential ingredients of creative work.

Relationships and the cost of eccentricity

Mullis married four times and had three children. His memoir and interviews are candid about the strains his lifestyle placed on relationships, from fiery romantic entanglements at Cetus to friendships tested by his outspoken views. Obituaries in major newspapers and magazines invariably mentioned his eccentricities alongside his scientific achievements, capturing a life that oscillated between acclaim and exasperation.

For readers of this Kary Mullis biography, those details matter not as gossip but as context: they show how the same traits that fuelled innovation – independence, disdain for authority, appetite for risk – also made sustained collaboration and stability difficult.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Kary Mullis

Life after the Nobel Prize

Winning the Nobel Prize in 1993 did not turn Mullis into an elder statesman of science. Instead, he became a travelling lecturer, consultant and occasional expert witness, appearing in court cases and on conference stages with equal flair. He consulted for biotech companies, dabbled in UV-sensitive materials and launched quirky ventures such as selling jewelry containing amplified DNA from famous dead people.

These ventures add colour to the Kary Mullis biography, but they also underline a basic fact: after PCR, there was no single project that defined his career. The invention that had brought him global fame remained his central contribution, even as he chased new ideas.

Illness, death and immediate legacy

Mullis died on 7 August 2019 in Newport Beach, California, reportedly from complications of pneumonia and heart disease. Tributes from scientists and commentators were strikingly mixed. Some celebrated the PCR pioneer whose insight had saved countless lives and enabled modern genomics; others emphasised the damage done by his AIDS denial and climate skepticism.

That tension is impossible to resolve fully, but a balanced Kary Mullis biography can at least make it visible: a life that combined extraordinary scientific creativity with public stances that often ran directly against the best available evidence.

The Lasting Legacy of the Kary Mullis Biography

Separating the invention from the inventor

Decades after the Mendocino highway epiphany, polymerase chain reaction is woven so deeply into molecular biology that students learn it as basic lab technique, not as recent innovation. That is the most tangible measure of Mullis’s impact. Long after individual controversies fade, PCR remains the quiet engine in thousands of experiments each day, a permanent fixture in the story told by any serious Kary Mullis biography.

What the Kary Mullis biography tells us about modern science

At the same time, the Kary Mullis biography is a cautionary tale. It reminds us that scientific authority is domain-specific; a Nobel Prize in Chemistry does not make someone an expert in epidemiology or climate science. It shows how media fascination with eccentric geniuses can blur the line between robust evidence and provocative opinion. And it illustrates how tools created for good – like PCR – can be misunderstood or misrepresented in public debates.

Understanding the Kary Mullis biography helps us understand something larger about our world: the double-edged nature of scientific progress. Breakthroughs such as PCR transform medicine, forensics and basic research, but they also depend on a culture that can celebrate disruptive thinkers while still insisting that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof.

In that sense, revisiting this Kary Mullis biography is not just an exercise in scientific history. It is a way of thinking about how we, as citizens and readers, navigate the promises and perils of modern science – and how we honour the inventions that change our lives without uncritically endorsing every idea voiced by their inventors.

Frequently Asked Questions about Kary Mullis Biography

Q1: Who was Kary Mullis and why is his biography important?

Q2: What exactly did Kary Mullis invent with PCR?

Q3: How did Kary Mullis's early life influence his later scientific work?

Q4: Why is Kary Mullis criticised for his views on HIV and AIDS?

Q5: How has PCR affected everyday life beyond the lab?

Q6: What can we learn from the contradictions in Kary Mullis's life story?