The rain clung to her parka, the mist swallowing the volcanic slopes as she crawled through mud and bamboo toward a family of mountain gorillas. In that moment, Dian Fossey was not a visiting scientist or a tourist on safari; she was an intruder trying to earn the trust of animals that had every reason to fear humans. Any serious Dian Fossey biography begins in this thin, cold air of Rwanda’s Virunga Mountains, where a solitary woman chose to share her life with an endangered species and, in doing so, changed the story of wildlife conservation forever.

Her name is now inseparable from the phrase “gorilla conservation pioneer.” Yet the path that led her from a difficult childhood in San Francisco to the high ridges between Rwanda and what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo was anything but straightforward. Fossey’s story is one of obsession as much as idealism, of small moments of tenderness with animals and fierce confrontations with people, and of a life that ended violently in the place she loved most.

This is not just the tale of a single scientist. Told properly, the Dian Fossey biography is also a chapter in primatology history, in 20th-century conservation science and in the ongoing global argument about how far we are prepared to go to protect other species. Her work helped pull mountain gorillas back from the brink of extinction, but it also forced the world to confront uncomfortable questions about power, colonial legacies and who gets to speak for wildlife.

At a glance: who was Dian Fossey?

Before diving into the details of the Dian Fossey biography, here is the story in brief:

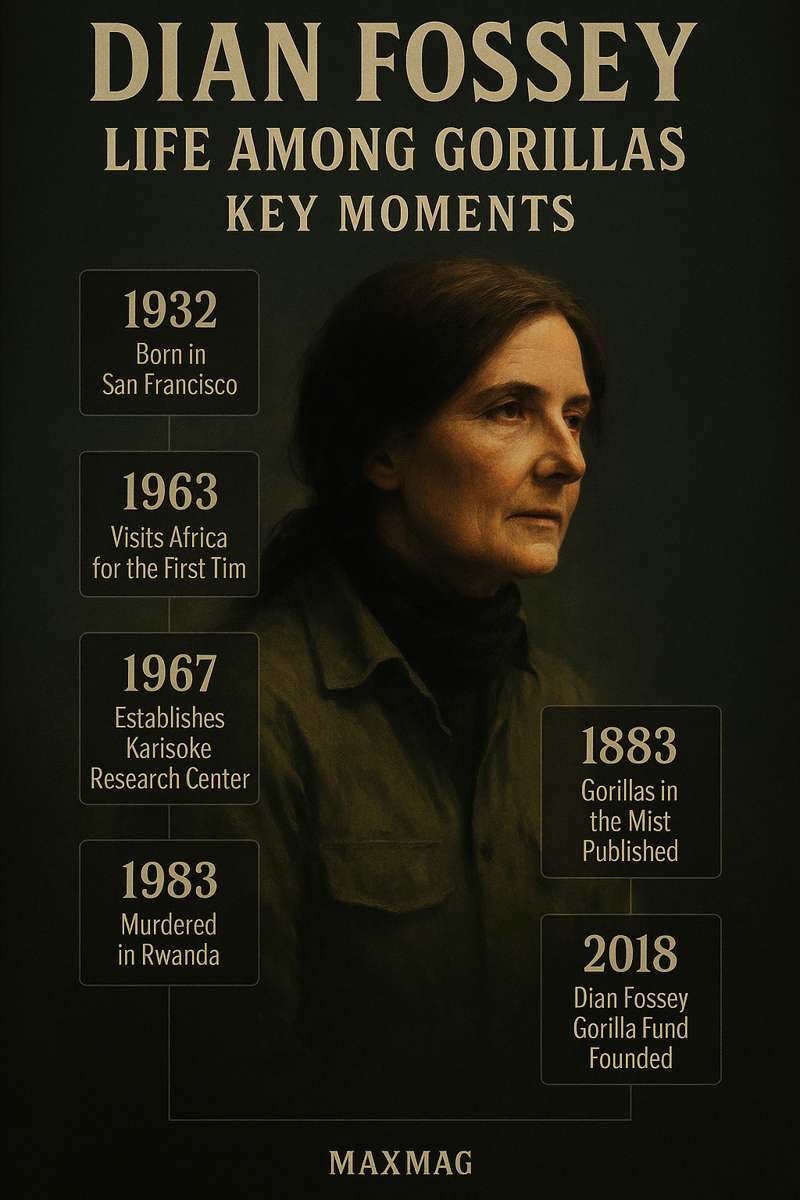

- American primatologist born in 1932, San Francisco, California.

- Field: primatology and wildlife conservation, focused on mountain gorillas in Rwanda’s Virunga Mountains.

- Founded the Karisoke Research Center in 1967 to study and protect gorillas in Volcanoes National Park.

- Author of the landmark book Gorillas in the Mist, which helped redefine public perceptions of great apes.

- Murdered in 1985 at her remote cabin in Rwanda, her death still surrounded by speculation and unresolved questions.

- Her work continues through the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International and modern gorilla conservation programs.

Early Life and Education: The First Chapters of the Dian Fossey biography

Childhood in San Francisco and a restless imagination

Dian Fossey was born on January 16, 1932, in San Francisco, into a family that looked stable from the outside but was emotionally fractured from early on. Her parents divorced when she was still a child, and a strict stepfather would come to dominate the household. Formal affection was scarce, and Fossey often sought refuge in books, horses and animals rather than in people. That combination of emotional distance from her human family and acute sensitivity toward non-human creatures would echo through the rest of the Dian Fossey biography.

Horses were her first obsession. As a teenager she became a strong rider, working in stables and finding in those animals a kind of honest companionship she rarely felt at home. The discipline of caring for large, powerful animals, learning their moods and movements, trained her eye and her patience. Long before she saw her first gorilla, she was already learning how to watch another species closely without demanding that it bend to her will.

From misfit student to committed therapist

Academically, Fossey’s path was uneven. She studied at the College of Marin and later at San Jose State College, where she eventually earned a degree in occupational therapy. She was not yet the iconic primatologist who would reshape conservation; she was a young woman trying to find a stable profession in post-war America. Her work with disabled children and adults taught her how to listen to bodies and behaviors rather than just words.

In occupational therapy, Fossey learned to observe small movements, to understand how tiny adjustments could change a person’s quality of life. Those clinical skills, rooted in compassion and attention, would later translate unexpectedly well to field research. The mountain gorillas she would come to know in Rwanda did not speak, in any human sense, but they communicated volumes with a glance, a chest beat, a shift of weight on a branch.

Saving for a dream: Africa on the horizon

By the early 1960s, Fossey felt restless. She was working in a hospital in Louisville, Kentucky, well regarded by colleagues but increasingly aware that a conventional life in American healthcare would never satisfy her. When she first encountered photographs and writings about Africa’s wildlife, something clicked. She took out a bank loan, saved obsessively and in 1963 finally booked a trip that would bend the entire Dian Fossey biography toward the African continent.

On that first journey, she visited Olduvai Gorge and met the paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey and his wife Mary, whose work on human origins had already attracted international attention. Leakey was intrigued by her intensity and her clear love for animals. At the time, he was quietly assembling what would become the legendary trio of “Trimates”: Jane Goodall for chimpanzees, Birutė Galdikas for orangutans and, he suspected, Dian Fossey for gorillas.

How the Dian Fossey biography turns to Africa and the birth of big ideas

A Dian Fossey biography shaped by Louis Leakey

If there is a single turning point in the Dian Fossey biography, it is the moment Louis Leakey decided she might be the right person to live among wild gorillas. Three years after that first encounter at Olduvai, he wrote to her with a proposition: return to Africa, not as a tourist but as a long-term researcher. She would have to leave her job, her relationships and the only life she knew. She said yes.

Leakey believed that women, often socialized to observe and to nurture, could be unusually effective in long-term fieldwork with great apes. Fossey, like Goodall before her, arrived in East and Central Africa with little formal training in primatology but immense determination. Out of that gamble grew a new era in primate science and a set of field methods that would influence primatology history for decades.

Crossing into the Virunga Mountains

In 1966, Fossey began her first serious attempts to study mountain gorillas in what was then the Congo, only to be forced out by political instability. By 1967, she had shifted to Rwanda and founded the Karisoke Research Center in the saddle between Mount Karisimbi and Mount Bisoke, more than 3,000 meters above sea level. There, amid constant rain and cold, a different kind of science took shape.

The gorillas she encountered were not used to benign humans. Many had only ever seen poachers. To get close enough to study them, she had to build trust one small gesture at a time. Fossey crawled on her knuckles, mimicked their vocalizations, chewed the same plants and averted her gaze when a silverback looked uneasy. These were not standard lab protocols; they were acts of immersion, rooted in the idea that to understand another species, you must meet it on its own terms.

The birth of a gorilla conservation pioneer

As weeks turned into months, she watched family groups form, split and reunite. She learned to recognize individuals by their noses, scars and idiosyncrasies. Her notebooks filled with data on diet, social hierarchy, maternal behavior and vocal patterns. But alongside the tables and sketches, another realization took hold: the mountain gorillas were in danger of disappearing within her lifetime. In those damp tents and rough wooden cabins, the Dian Fossey biography stopped being just a story of scientific curiosity and became the story of a gorilla conservation pioneer willing to confront anyone she believed threatened her study animals.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Dian Fossey

Karisoke: a laboratory in the clouds

From 1967 onward, Karisoke became the beating heart of Fossey’s career. At its peak, the camp housed trackers, local staff and visiting students, all focused on one thing: observing mountain gorillas in their natural habitat day after day. The Karisoke Research Center produced detailed long-term records of individual gorillas and family groups, providing a data set that modern conservation scientists still use.

Among her most important findings were insights into gorilla social behavior. She documented how females transfer between groups, how males compete and cooperate, and how young gorillas learn through play. She described vocal repertoires and subtle gestures that revealed a rich emotional life behind their imposing frames. In an era when gorillas were still widely seen as fearsome brutes, her records painted a different picture: dignified, gentle apes with complex social bonds.

Gorillas in the Mist and the popular Dian Fossey biography

In 1983, Fossey published Gorillas in the Mist, a book that wove her field notes, personal experiences and conservation battles into a single narrative. More than any scientific article, this book shaped the public’s understanding of mountain gorillas and cemented the Dian Fossey biography in popular culture. It was part natural history, part memoir, part warning.

Readers met individual gorillas as characters rather than specimens: Digit, the young male who would later be killed; the imposing silverbacks who tolerated her presence; the shy infants whose curiosity slowly overcame their fear. Fossey’s language was often lyrical, at times sentimental, but it never lost sight of the ecological stakes. She argued that gorillas were not only worthy of protection; they were mirrors, revealing both the best and worst of human behavior.

How Gorillas in the Mist cemented the Dian Fossey biography in culture

The book’s success led to the 1988 film adaptation of the same name, starring Sigourney Weaver. While the film simplified and dramatized events, it fixed Fossey in the global imagination as a fierce, uncompromising defender of nature. The phrase Dian Fossey biography became shorthand for a certain kind of environmental heroism: a lone scientist living in extreme conditions, sacrificing personal comfort for a cause that transcended her own life.

That cultural image had tangible effects. Donations to gorilla conservation increased, and eco-tourism began to grow, bringing money into Rwanda and neighboring countries. At the same time, it risked flattening a complicated woman into a single archetype: the saintly martyr of the Virungas. Later accounts, including memoirs by former staff and a critical reassessment by biographers, would complicate that picture, revealing a more contradictory and sometimes troubling personality.

Scientific legacy and modern conservation science

Scientifically, Fossey’s data helped prove that mountain gorillas are not naturally aggressive toward humans and that, with patience and respect, they can be habituated without losing their wild behaviors. Those findings underpin today’s carefully managed gorilla tourism and anti-poaching strategies. Modern articles on the species’ recovery, such as a Smithsonian overview of mountain gorilla recovery, trace a direct line from her early patrols and field observations to today’s more sophisticated conservation programs.

Her work also fed into broader debates in 20th-century conservation science about the role of field biologists as advocates. Should scientists remain detached observers, or do they have a responsibility to intervene when the species they study is under threat? Fossey’s answer was clear: neutrality, in the face of extinction, was not an option.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Living like a local in the forest

Fossey’s methods were immersive to a degree that startled some of her contemporaries. She lived year-round at high altitude, in makeshift huts and later a basic cabin, enduring constant mud, cold and isolation. Students who joined her often found the conditions unbearable. Paths had to be hacked out each day with machetes through head-high vegetation; food and supplies were carried in by porters on narrow, slippery trails.

This rough physical existence was not incidental to her science; it was part of it. Fossey believed that only by matching, as far as possible, the gorillas’ daily rhythms could she begin to see the forest as they did. She rose early, tracked them for hours and often returned in darkness. The rhythm of the Karisoke camp was dictated not by conferences or grant deadlines but by the movements of gorilla families across the slopes.

Collaborating, but on her own terms

Although she is often portrayed as a solitary figure, Fossey did collaborate with other scientists, photographers and institutions. The National Geographic Society provided crucial financial support and global visibility. She worked with field assistants from Rwanda and neighboring regions, whose tracking skills and local knowledge were indispensable. Yet she remained protective, sometimes fiercely so, of her study site and her data.

This controlling streak strained relationships with visiting researchers and students. Some later described a camp atmosphere that could swing from inspiring to hostile, depending on Fossey’s mood and her perception of others’ loyalty. For a modern reader of the Dian Fossey biography, these accounts are a reminder that scientific pioneers are rarely easy colleagues. The same ferocious dedication that safeguarded the gorillas also made her resistant to compromise.

Field methods that changed primatology

At a technical level, Fossey helped refine what primatologists now call “habituation”: the gradual process of getting wild animals used to human observers without food rewards or force. Instead of feeding gorillas, she mimicked their behaviors and respected their personal space, allowing them to set the pace of contact. Over time, juveniles came closer, sometimes touching her or investigating her equipment.

Her detailed field notes, photographs and later film footage created a template for long-term behavioral studies of great apes. In this sense, the Dian Fossey biography sits alongside those of Jane Goodall and Birutė Galdikas as a cornerstone of modern primate research, shaping how scientists design and interpret studies of our closest relatives.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

The ‘war on poachers’

Fossey is often celebrated as a hero who stood up to poachers, and there is truth in that. She organized patrols to dismantle snares, confronted men she believed were killing gorillas and used funds from what she called the Digit Fund to support anti-poaching work. But her tactics could be extreme. Some accounts describe her capturing poachers, humiliating them, even physically punishing those she considered repeat offenders.

Supporters argue that she was operating in a context where official law enforcement was weak, underfunded and sometimes corrupt. Critics counter that her approach reflected an older, colonial style of conservation that treated local communities as enemies rather than partners. Any honest Dian Fossey biography has to hold both truths: she helped save gorillas and, at times, harmed relationships with the very people whose cooperation would be essential for long-term conservation.

Accusations of racism and cultural blindness

In recent years, scholars and activists have revisited Fossey’s writings and actions through a more critical lens. Some of her descriptions of local people are framed in starkly negative terms, and former colleagues recall moments in which she expressed open contempt for those she believed were complicit in poaching. These stories raise uncomfortable questions about how race, power and privilege operated in her work.

It is tempting to smooth these edges out of the Dian Fossey biography, to keep the comforting picture of a pure conservation saint. But doing so would erase the very tensions that make her story important to current debates. Modern gorilla conservation organizations in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo now emphasize community-based approaches, recognizing that long-term protection depends on local people seeing economic and cultural value in keeping gorillas alive. In many ways, their work is both an extension of and a correction to Fossey’s legacy.

Myths from page, screen and rumor

The success of Gorillas in the Mist and its film adaptation also generated myths. Some viewers came away believing that Fossey single-handedly saved the mountain gorillas or that she was universally beloved by her staff and neighbors. Later investigations and memoirs show a more complicated reality, with internal disputes, professional rivalries and serious questions about her mental health in the years before her death.

A deeper reading of the Dian Fossey biography reveals a person who could be generous and inspiring one day, paranoid and confrontational the next. These contradictions do not erase her achievements, but they do remind us that social movements and scientific revolutions are often driven by flawed individuals.

Impact on Primatology and on Wider Society

Rewriting the image of the gorilla

Before Fossey, gorillas in popular culture were often monsters: King Kong on the Empire State Building, rampaging beasts in pulp magazines. Her writings and photographs helped replace that caricature with what she called “gentle giants,” highly social animals with intricate family lives.

This shift in perception mattered. When people saw gorillas as savage, their disappearance could be shrugged off as inevitable or even welcome. Once the public began to see them as intelligent, vulnerable beings with emotions, their possible extinction became a moral problem. The Dian Fossey biography thus contributed not just to primatology, but to a broader cultural shift in how humans view non-human animals.

From field station to global charity

After her death, the Digit Fund she founded was renamed the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International. Now based in Atlanta, it operates research, education and community programs across Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, continuing and expanding the work she began at Karisoke.

Through school programs, local employment, health initiatives and scientific training, these organizations embody a more holistic vision of conservation than was common in Fossey’s day. Yet they still trade on the power of her story. Donors respond to the narrative of a woman who gave her life for gorillas, and that narrative, the living Dian Fossey biography, continues to generate resources that protect animals on the ground.

Influence on global conservation debates

Fossey’s example sits at the intersection of several ongoing arguments in conservation: Should reserves prioritize strict protection or sustainable use? How much should tourism be encouraged as a source of funding? Who should control conservation policy in post-colonial nations? Her skepticism about mass tourism clashes with today’s reality, in which carefully managed gorilla trekking provides vital income for governments and communities.

At the same time, her insistence that conservation cannot be effective without tackling poaching and corruption remains highly relevant. For many activists and scientists, the Dian Fossey biography serves as a cautionary tale about both the power and the limits of individual heroism in environmental struggles.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Relationships, solitude and the pull of the forest

Fossey’s personal life was marked by intense relationships and long stretches of solitude. She had romantic ties, including an engagement and later a complex partnership with photographer Bob Campbell, but those relationships were often overshadowed by her commitment to the gorillas and to Karisoke.

In her cabin, she kept a menagerie of rescued animals: dogs, a monkey, injured birds. These companions, along with the gorillas themselves, formed a kind of chosen family. Former colleagues describe evenings of laughter and storytelling around kerosene lamps, but also periods when she withdrew into herself, smoking heavily and brooding over perceived enemies.

Beliefs about animals and humans

Fossey believed that animals, especially gorillas, possessed emotional and moral qualities that many humans underestimated. She wrote of their patience, their gentleness, their capacity for grief and affection. At the same time, she could be harsh in her judgments of people, especially those she believed were harming the forest.

This sharp contrast runs through the Dian Fossey biography: a woman capable of great tenderness toward animals and great suspicion toward humans. Some saw in this a kind of misanthropy, a belief that humanity as a whole was fundamentally destructive. Others interpreted it as the understandable response of someone who had spent years watching poachers dismantle the lives of the creatures she loved.

Later Years and the Final Chapter of Dian Fossey’s Life

Escalating tensions and personal strain

By the early 1980s, Fossey was internationally famous but increasingly isolated at Karisoke. Her “war” against poaching intensified, as did her conflicts with park authorities and some international conservation groups who favored tourism-based strategies. She feared that poorly managed tourism would stress gorillas and expose them to disease.

At the same time, accounts from visitors and staff suggest that her mental health was deteriorating. She became more suspicious, convinced that people were plotting to undermine her work or steal her data. The final pages of the Dian Fossey biography are filled with this sense of siege: a scientist at odds with institutions she believed should have been her natural allies.

The night of the murder

On December 27, 1985, Fossey was found murdered in her cabin at Karisoke, her skull split by a machete blow. The room had been ransacked, but money and valuables remained, complicating the theory of simple robbery. Rwandan courts later convicted her American research assistant in absentia, but he denied involvement, and the evidence has long been disputed.

Other theories point to poachers seeking revenge, to political interests angered by her opposition to certain development policies, or to personal vendettas. A detailed New Yorker narrative on Dian Fossey’s death captures the atmosphere of rumor and unanswered questions that followed. To this day, no consensus exists about who killed her or why.

Burial among the gorillas

Fossey was buried in the gorilla graveyard at Karisoke, near the bodies of Digit and other gorillas killed by poachers. Visitors to the ruins of the camp still see her simple grave, marked by a stone bearing her name. That choice of resting place closes the physical circle of the Dian Fossey biography: she now lies in the same forest where she spent her most intense years, protected, in a sense, by the animals she tried to protect.

The Lasting Legacy of the Dian Fossey biography

From near extinction to cautious recovery

When Fossey began her work, estimates suggested that only a few hundred mountain gorillas remained in the wild. Poaching, habitat loss and political instability all threatened to push them over the edge. Thanks in part to her early interventions, and to the organizations that followed, mountain gorilla numbers have since climbed into the hundreds, with some surveys suggesting more than 1,000 individuals today.

This rebound is one of conservation’s rare good-news stories, and the Dian Fossey biography occupies a central place in that narrative. Yet it is a fragile success, dependent on continued funding, political stability and careful management of tourism. The lessons of her life — the dangers of ignoring local communities, the importance of long-term research, the costs borne by individuals who challenge powerful interests — remain as relevant as ever.

How her story shapes modern conversations

Today, when conservationists debate how to balance strict protection with community needs, or how to navigate the ethics of wildlife tourism, Fossey’s name still surfaces. Her legacy is invoked both by those who stress the urgency of defending endangered species and by those who argue that conservation must address historical injustices and present-day inequalities.

Understanding the Dian Fossey biography helps us understand more than one woman’s life. It illuminates the tangled relationships between science and storytelling, between Western researchers and African landscapes, between individual passion and systemic change. Above all, it forces us to ask what we owe to other species — and what we are willing to risk, or sacrifice, to keep them from vanishing into the mist.

Frequently Asked Questions about Dian Fossey biography

Q1: Who was Dian Fossey and why is the Dian Fossey biography so influential?

Q2: What were Dian Fossey's main scientific contributions to primatology?

Q3: How did Dian Fossey help protect mountain gorillas from extinction?

Q4: Why was Dian Fossey a controversial figure in conservation history?

Q5: What do we know about Dian Fossey's murder and the investigations that followed?

Q6: How can someone today continue the work described in the Dian Fossey biography?