On a cold November day in 2011, news spread that Lynn Margulis had died at 73, after a stroke at her home in Amherst, Massachusetts. For most people outside science, the name barely registered. Yet anyone who has spent time with a serious Lynn Margulis biography soon discovers a story as disruptive as any in modern biology: a scientist who insisted that cooperation, not just competition, runs evolution, and who refused to back down even when almost everyone told her she was wrong.

This Lynn Margulis biography is also the story of how a young Chicago student became one of the twentieth century’s most stubborn and imaginative evolutionary thinkers. Her serial endosymbiosis theory – the idea that key parts of our cells began as independent bacteria – helped to rewrite cell evolution. Her collaboration on the Gaia hypothesis, which described Earth as a self-regulating system, pushed biology into conversation with planetary science. And along the way, she built a reputation as a scientific rebel who delighted in argument as much as in microbes.

At a glance:

- Who: Lynn Margulis, American evolutionary biologist and microbiologist.

- Field and era: Evolutionary biology and geosciences, mainly from the 1960s to the early 2000s.

- Headline contribution: Developed modern endosymbiotic theory, showing that complex cells evolved through long-term cooperation between microbes.

- Why she matters now: Her work underpins today’s symbiosis-rich view of life and shapes debates in microbiology, ecology and astrobiology.

What follows is not just a list of dates and papers, but a narrative Lynn Margulis biography: the early defiance, the landmark 1967 article that journals kept rejecting, the heated arguments with neo-Darwinists, the international honours, and the messy, sometimes uncomfortable controversies that came later. Together, they sketch a life spent insisting that living things – including humans – are far more entangled with microbes and with each other than we like to imagine.

Early Life and Education in the Lynn Margulis biography

Chicago beginnings in the Lynn Margulis biography

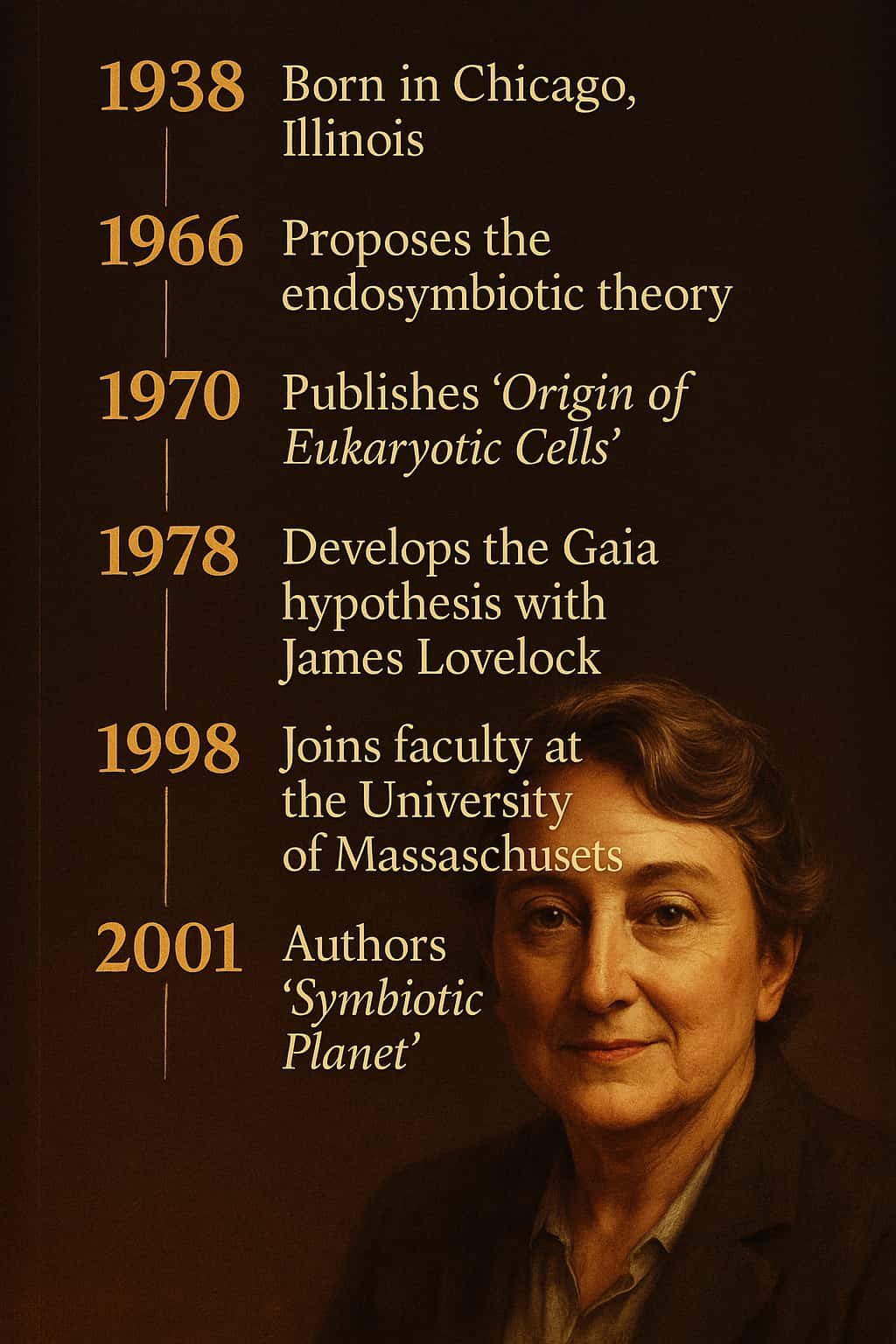

Lynn Petra Alexander was born on 5 March 1938 in Chicago, Illinois, the eldest of four daughters in a Jewish family. Her father, Morris, was a lawyer who also ran a small road-paint company, and her mother, Leona, managed a travel agency. It was not an obviously scientific household, but it was one that valued argument and independence – traits that would become central to any serious Lynn Margulis biography.

As a teenager she attended Hyde Park High School, close to the University of Chicago. By her own account she was not a model pupil, more interested in books and conversation than in behaving. But she was precocious. At fifteen she entered the University of Chicago’s Laboratory Schools and quickly gravitated towards science, drawn by the sense that biology still had deep unanswered questions about life itself.

Universities, mentors and first experiments

Margulis earned a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts from the University of Chicago in 1957, but her interests were already narrowing towards genetics and protozoa – single-celled organisms that seemed to blur the line between plants and animals. She moved to the University of Wisconsin–Madison for a master’s degree in genetics and zoology, working on Euglena, a microscopic swimmer that photosynthesises like a plant but moves like an animal.

Those early studies introduced her to the world of organelles – mitochondria, chloroplasts, and other tiny compartments inside cells. She learned that these structures had their own membranes and curious behaviours. The textbooks presented them as standard fixtures of complex cells. Margulis began to suspect that the standard story was incomplete.

For her PhD, she went to the University of California, Berkeley, studying cell biology under zoologist Max Alfert. At the same time, she took a research post at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, juggling life as a young mother – she had married fellow student Carl Sagan and already had children – with demanding lab work. That interplay between personal upheaval and relentless science appears in nearly every nuanced Lynn Margulis biography, because it shaped both her ambition and her impatience with institutions that underestimated her.

Lynn Margulis biography and the Birth of Her Big Ideas

“On the Origin of Mitosing Cells” and the endosymbiotic leap

Any Lynn Margulis biography has to linger over a single paper: “On the Origin of Mitosing Cells”. Written in the mid-1960s, when she was still publishing under her first married name Lynn Sagan, it proposed a bold answer to a longstanding puzzle: where did the complex cells of animals, plants and fungi come from?

The serial endosymbiosis theory she laid out suggested that mitochondria and chloroplasts began life as independent bacteria. Long ago, she argued, these free-living microbes entered into other cells and set up permanent residence. Over millions of years they became indispensable partners, turning what began as symbiosis – living together – into a single, integrated cell.

At the time, evolutionary biology was dominated by neo-Darwinism, which treated random mutation and natural selection as the main engines of change. Margulis did not reject those forces, but she thought they were only part of the story. Her endosymbiotic theory presented symbiosis itself as a creative engine of evolution: cells could acquire new abilities not just through slow mutation, but by merging with other organisms.

Journals were not impressed. The manuscript was reportedly rejected by more than a dozen editors before the Journal of Theoretical Biology finally published it in 1967. For years, many colleagues dismissed it as imaginative but unlikely. A careful Lynn Margulis biography has to capture this long, grinding resistance: the conferences where she was told her ideas were “too speculative”, the slow accumulation of evidence from molecular biology, and the eventual, grudging shift towards acceptance.

From theory to evidence: symbiogenesis vindicated

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, advances in genetics transformed the debate. Researchers showed that mitochondria and chloroplasts have their own DNA, distinct from the DNA in the cell nucleus, and that this genetic material closely resembles bacterial genomes. This was exactly what serial endosymbiosis theory predicted. Over time, endosymbiotic theory moved from fringe speculation to textbook orthodoxy.

For Margulis, it was vindication, but not closure. She continued to refine the theory, elaborating how multiple symbiotic events – not just one merger – shaped cell evolution. Her books, including Origin of Eukaryotic Cells and Symbiosis in Cell Evolution, presented a sweeping history of life dominated by microbial mergers. Today, university courses on evolution routinely describe endosymbiosis, often drawing on resources like the University of California, Berkeley’s clear overview of Margulis’s work on endosymbiotic theory, which traces how her ideas reshaped the history of evolutionary thought.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Lynn Margulis

Endosymbiotic theory and the remaking of cell evolution

A central thread in the Lynn Margulis biography is serial endosymbiosis theory itself. It did more than relocate a few organelles; it reframed complex life as the product of ancient mergers. Mitochondria brought efficient energy production. Chloroplasts brought photosynthesis. Other, more speculative symbioses might underlie structures like cilia and flagella. Whether every detail of her symbiogenesis programme stands the test of time, the broader picture – that cooperation between species can drive evolutionary innovation – now permeates evolutionary biology.

Gaia and a living planet

Margulis’s collaboration with British chemist James Lovelock on the Gaia hypothesis pushed her far beyond microbiology. Gaia proposed that life and the physical environment form a tightly coupled system: organisms help regulate planetary conditions – like temperature and atmospheric composition – in ways that keep Earth habitable. In their joint papers, Margulis brought her intimate knowledge of microbes to Lovelock’s planetary models, arguing that bacterial metabolism plays a major role in shaping the atmosphere.

The earliest versions of Gaia were widely criticised as mystical or teleological, as if Earth itself were being presented as a conscious organism. Margulis insisted that no such mysticism was needed: feedback loops between microbes, plants, oceans and rocks could explain the apparent self-regulation. She argued that if you want to understand climate history, you must take microbial evolution seriously.

Five kingdoms, many microbes

Another recurring theme in any in-depth Lynn Margulis biography is her work on classifying life. She became one of the strongest proponents of the five-kingdom system – animals, plants, fungi, protists and prokaryotes – at a time when molecular biology was encouraging new schemes, such as Carl Woese’s three-domain model. Margulis thought that, despite its flaws, the five-kingdom system captured the ecological and structural differences that mattered most, especially for microbes.

In later years, as genetic data multiplied, most biologists moved away from five kingdoms. Margulis remained sceptical of the new taxonomies, seeing them as too abstract and too rooted in a gene-centred view of life. Whether one agrees or not, her insistence on including morphology, ecology and symbiosis in classification kept alive an important tension between DNA-based trees and a more organismal, ecological understanding of biodiversity.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Teaching, motherhood and the Lynn Margulis biography

For more than two decades at Boston University and then at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Margulis was not just a writer of landmark papers but a teacher and mentor. Students remember laboratories overflowing with cultures of microbes and with diagrams linking cell structures to evolutionary stories. She was famous for her rapid speech, her willingness to argue, and her expectation that students think for themselves rather than defer to authority.

The Lynn Margulis biography is, unusually for a scientist’s life, also a story about family. She married Carl Sagan in 1957, soon after her undergraduate degree, and they had two sons before divorcing in 1964. Later she married crystallographer Thomas Margulis and had two more children before that marriage also ended. She liked to say she had “quit her job as a wife twice” and was blunt about the difficulty of combining motherhood, marriage and high-level science.

Collaboration as a way of thinking

Margulis’s commitment to symbiosis in nature was mirrored in the way she worked. She often collaborated, most famously with her son Dorion Sagan, with whom she wrote a string of books that translated complex ideas in evolutionary biology into vivid prose for general audiences. Her partnerships with Lovelock and with other geoscientists showed a similar pattern: she brought deep microbiological knowledge and a fearless imagination; her collaborators often brought mathematical, geological or atmospheric expertise.

In interviews, she described science not as a detached, objective march towards truth, but as a messy human enterprise full of prejudices, fads and forgotten ideas. That sensibility runs through the best versions of the Lynn Margulis biography: a constant awareness that scientific consensus is contingent, and that outsiders can sometimes see connections insiders miss.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

A controversial chapter in the Lynn Margulis biography

Margulis revelled in scientific argument, but some of her positions drew harsh criticism. She was an outspoken critic of “ultra-Darwinism”, the gene-centric view popularised by figures like Richard Dawkins. She once said that natural selection “eliminates and maybe maintains, but it doesn’t create”, a line that infuriated colleagues who felt she was downplaying the creative power of mutation and selection.

In the 2000s, her scepticism extended into more problematic territory. She co-authored a paper suggesting that spirochete bacteria might play a direct role in AIDS, a claim that was at odds with the well-established role of HIV. Critics accused her of lending her reputation to AIDS denialism, and the episode is now widely seen as a serious misstep. In other interviews she voiced doubts about the official account of the 9/11 attacks, including suggestions of controlled demolition, further alienating many scientists who admired her earlier work.

Myths about Gaia and “mystical” science

Another persistent misconception in public discussions of the Lynn Margulis biography concerns the Gaia hypothesis. Popular books and documentaries sometimes present Gaia as if Margulis endorsed a literally conscious Earth. In fact, she repeatedly rejected that framing, emphasising that the hypothesis described feedback processes, not planetary intention. For her, Gaia was not a goddess to be worshipped but a set of coupled biological and geophysical cycles that deserved serious study.

These controversies complicate any attempt to turn her life into a simple story of heroic insight. They show a scientist whose scepticism could both illuminate and mislead, whose willingness to challenge consensus sometimes took her into cul-de-sacs. A balanced Lynn Margulis biography has to hold both realities at once.

Impact on Evolutionary Biology and on Wider Society

Re-centring microbes in the history of life

Margulis’s most enduring impact within evolutionary biology is the way she forced scientists to take microbes seriously as creative agents in evolution. By showing that major innovations – like the complex cell itself – likely arose from symbiosis, she helped launch what some historians of science call a “microbial turn” in evolutionary thinking. Today, research on microbiomes, horizontal gene transfer and symbiotic partnerships across the tree of life all echo themes she championed.

A good Lynn Margulis biography has to highlight how far-reaching that shift has been. Where older textbooks treated bacteria as primitive loners, modern accounts describe intricate networks of microbial cooperation, from lichens and coral reefs to the bacteria in our own guts. Margulis did not discover these relationships, but she provided a powerful conceptual framework – symbiogenesis – that encouraged biologists to see them as central rather than peripheral.

Influence beyond biology: from astrobiology to environmentalism

Beyond her own field, Margulis influenced emerging disciplines like astrobiology. NASA supported her work on microbial evolution and organelle heredity, recognising that understanding how life reshapes a planet is essential for searching for life beyond Earth. Profiles from NASA’s astrobiology programme describe her as a “scientific rebel” whose ideas about symbiosis and planetary life cycles helped shape how researchers think about habitable worlds.

Environmental thinkers and activists also seized on the Gaia metaphor, sometimes in ways that made mainstream scientists uneasy. Margulis herself was comfortable with that tension. She believed that seeing Earth as a dynamic, co-evolving system of life and rocks could foster a deeper sense of responsibility, even if the language occasionally slid into poetry.

Her public impact is captured powerfully in a Washington Post obituary, which described her as “a rebel within the realm of science” whose advocacy of symbiosis helped change evolutionary biology. That assessment, written in the immediate wake of her death, has aged well: much of what was once dismissed as heresy is now built into the way we teach the history of life. That nuanced Washington Post portrait of Lynn Margulis’s life and work remains a useful snapshot of how the scientific establishment came to terms with her influence.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Stubborn, funny, sometimes infuriating

Virtually every colleague’s recollection in a detailed Lynn Margulis biography mentions her personality. She was funny, earthy in her language, impatient with what she saw as intellectual laziness. She delighted in informal conversation as much as formal lectures, and she was perfectly happy to argue in public with famous figures in her field.

She described herself as an agnostic and a staunch evolutionist, but insisted that current evolutionary theory was incomplete. That combination – strong commitment to evolution, sharp criticism of how it was framed – often confused outsiders, who sometimes lumped her in with anti-evolutionists. She bristled at this, insisting that her quarrel was with a narrow, gene-centred view of evolution, not with the fact of evolution itself.

Relationships, losses and daily life

Away from the lecture hall, Margulis lived in a rambling house in Amherst, surrounded by books, papers and samples from fieldwork. Friends describe a chaotic, welcoming atmosphere, full of visiting students, collaborators and family. Her children – Dorion, Jeremy, Zachary and Jennifer – each navigated growing up in the orbit of a mother whose work often came first.

Later in life she formed a long-term partnership with Spanish biologist Ricardo Guerrero. They worked together on research and field courses, particularly in Spain, where Margulis developed a strong affection for certain landscapes. When she died, her ashes were scattered in some of her favourite research sites near Amherst – a final gesture that fits the ecological sensibility that runs through the Lynn Margulis biography.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Lynn Margulis

Honours and late-career recognition

By the 1990s and 2000s, Margulis was no longer a marginal figure. She was elected to the US National Academy of Sciences, awarded the US National Medal of Science, received the Darwin–Wallace Medal from the Linnean Society of London, and garnered honorary degrees from universities around the world. Scientific societies that had once ignored her now invited her as a keynote speaker and celebrated her as a pioneer of modern symbiosis research.

Yet even at the height of recognition, she remained outside the mainstream in certain respects. Her continued scepticism of gene-centric evolution, her defence of some unpopular scientific ideas, and her willingness to embrace colourful metaphors kept her at arm’s length from the most conservative corners of evolutionary biology.

Stroke, death and immediate reflections

On 22 November 2011, Lynn Margulis died after a haemorrhagic stroke at her home in Amherst. Colleagues from across the world wrote tributes, many of them published in journals like Science, Nature and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. They remembered a “visionary biologist”, a “tireless champion of the microbial world”, and a scholar who forced others to grapple with ideas they would rather have ignored.

In these memorials, we see the closing pages of the Lynn Margulis biography: a once-mocked idea now central to textbooks; a once-maverick scientist now hailed as a major figure in twentieth-century science; and a set of unresolved debates about where the balance lies between mutation, selection and symbiosis in the grand story of life.

The Lasting Legacy of Lynn Margulis biography

If there is a single thread that runs through the Lynn Margulis biography, it is the insistence that life is more collaborative and more entangled than our stories usually allow. Her serial endosymbiosis theory made it impossible to think of complex cells as isolated inventions; they are living mosaics of ancient partnerships. The Gaia hypothesis, stripped of its mystical misreadings, invited scientists to see life and planet as a coupled system, not as separate stages and actors.

Her intellectual legacy lives on in multiple ways: in the widespread acceptance of endosymbiotic theory; in the explosion of microbiome research that treats symbiosis as routine; in astrobiology’s search for planetary signatures of life; and in environmental thought that borrows her planetary perspective. Even the controversies that clouded her later years serve as a reminder that the same stubbornness that fuels great insights can also lead thinkers into error.

Understanding the Lynn Margulis biography does more than honour a single scientist. It refines our picture of evolution itself, from a brutal contest of isolated individuals to a sprawling, messy history of alliances, mergers and feedback loops. In an era when human actions are transforming Earth’s systems, that shift in perspective – from separation to entanglement – may be her most important gift.

Frequently Asked Questions about Lynn Margulis biography

Q1: Who was Lynn Margulis, in simple terms?

Q2: What is endosymbiotic theory in the Lynn Margulis biography?

Q3: How is the Gaia hypothesis connected to Lynn Margulis?

Q4: Why was Lynn Margulis considered controversial?

Q5: How has the Lynn Margulis biography influenced modern evolutionary biology?

Q6: What should I read if I want to explore the Lynn Margulis biography further?