To tell an Ernst Mayr biography is to trace the arc of a century in which biology reinvented itself. When he was born in 1904, evolution was still a contested idea and genetics a young science; by the time he died, in 2005, evolutionary biology had become a mature discipline with its own theories, institutions and public debates – many of them shaped directly by him.

Across that long life, the Ernst Mayr biography weaves together unlikely strands: a bird-obsessed teenager in provincial Germany; a young doctor who abandoned medicine for tropical expeditions; an émigré curator at the American Museum of Natural History; a Harvard professor who argued passionately about what a species really is; and, in his later years, a philosopher of biology who insisted that life could not simply be reduced to physics or to genes alone.

Ernst Mayr biography at a glance

- Who: Ernst Mayr (1904–2005), German-born American evolutionary biologist, ornithologist and philosopher of biology.

- Field and era: Architect of the 20th-century “modern synthesis” of Darwinian evolution and genetics; a leading evolutionary biology pioneer.

- Headline contributions: The biological species concept theory, major work on speciation and peripatric speciation, and a powerful defence of “population thinking” over fixed racial or typological views of life.

- Why he matters today: From debates about what counts as a species to arguments over race, human nature and the limits of reductionism, much of modern science still lives in the world the Ernst Mayr biography helped create.

Early Life and Education of Ernst Mayr

From Bavarian childhood to bird-mad teenager

Ernst Mayr was born on 5 July 1904 in Kempten, in the Bavarian Alps, the second son of a lawyer who loved natural history and took his children on field trips. Those early walks, and access to a popular science magazine called Kosmos, helped turn a bright boy into an obsessive birdwatcher. When the family moved to Dresden after his father’s death, the city’s gymnasium and nearby wetlands became his real classroom. At 18, he joined the Saxony Ornithologists’ Association and began rubbing shoulders with older naturalists who recognised his talent.

The key figure was Erwin Stresemann, a leading ornithologist at the Berlin Museum of Zoology. Stresemann quickly decided that Mayr, who could already identify local birds on the wing, had the sharp eye and patience required of a systematist – someone who sorts the living world into meaningful categories. In an episode that appears in almost every serious Ernst Mayr biography, Stresemann challenged the student to distinguish nearly identical treecreepers from museum skins; Mayr passed, and with that test, his future in biology was effectively sealed.

Medicine abandoned for evolution

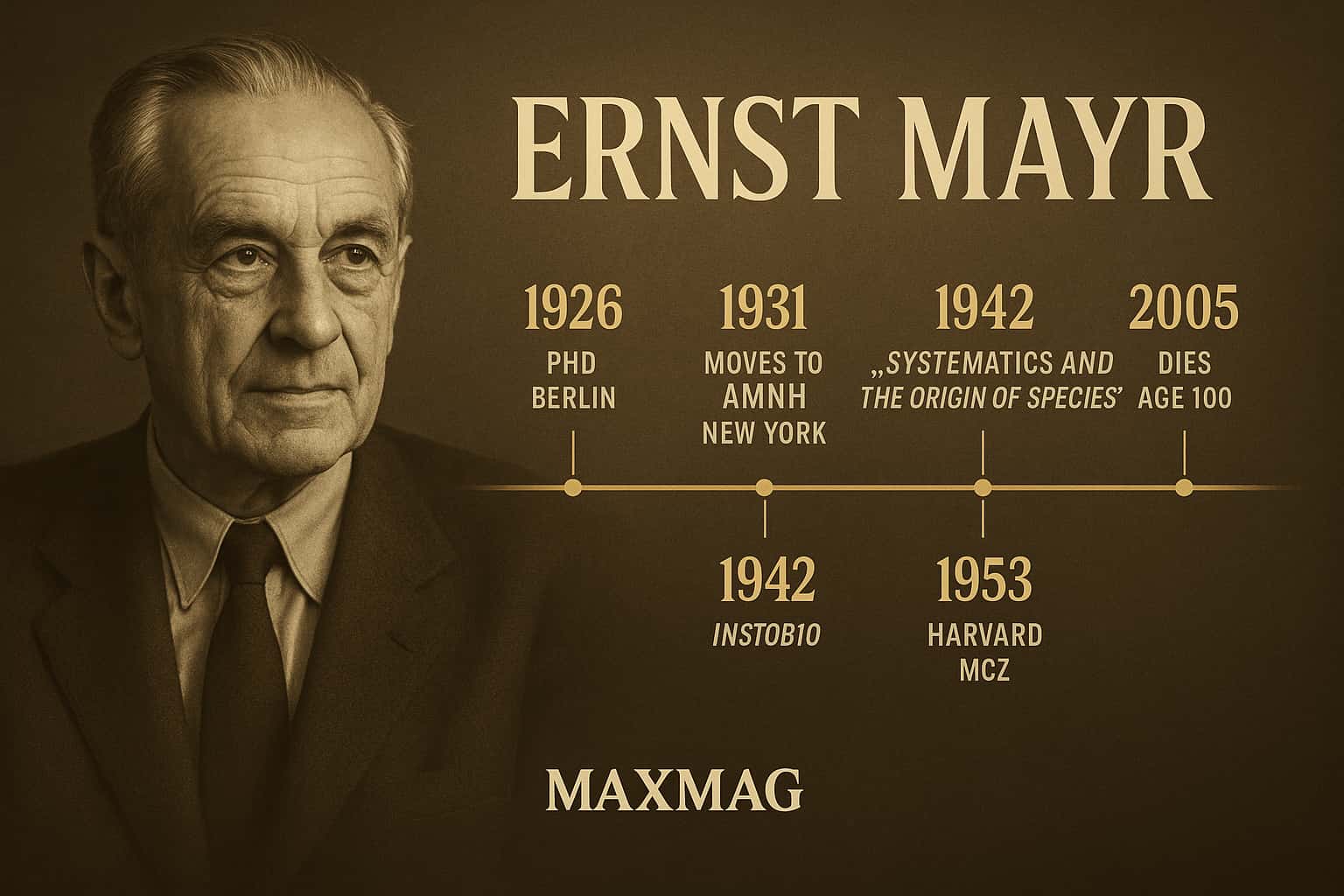

Formally, Mayr entered the University of Greifswald to study medicine, a respectable path in a Germany still recovering from the First World War. Informally, he spent as much time as possible birding and haunting museum collections. Stresemann eventually pushed him to make a choice: either remain in medicine or commit to biology and take a position at the museum – on condition he finish a doctorate in just 16 months. Mayr accepted, completed a PhD in ornithology at the University of Berlin in 1926, and never looked back.

That early turning point is more than a colourful detail in the Ernst Mayr biography. It marks the moment a would-be surgeon became a field naturalist and theorist, one whose later ideas about species, variation and evolutionary history grew out of staring at real birds in real landscapes rather than equations on paper.

Ernst Mayr biography and the Birth of Their Big Ideas

Field expeditions that colour any Ernst Mayr biography

If you picture the young Ernst Mayr, do not imagine a quiet academic behind a desk. Picture instead a lean figure hacking through New Guinea rainforest, a rifle over his shoulder, chasing birds of paradise for the Whitney South Sea Expedition. In 1928 he travelled through terrain that, to European science, was almost entirely unknown. The journey yielded thousands of bird skins and dozens of species new to science; Mayr would eventually name 38 new bird species and a similar number of orchids.

These expeditions, recounted vividly in interviews and memoirs, did more than fill museum drawers. They taught Mayr how populations vary from valley to valley, island to island. He saw that what looked like a single species in one place could be subtly different in another – differences that might eventually harden into separate species. The wilderness of the Cyclops Mountains and the Solomon Islands became, in effect, his outdoor laboratory in evolutionary biology history.

From red-crested pochard to species questions

One favourite story in the Ernst Mayr biography takes place not in the tropics but on a lake near Dresden. As a teenager, Mayr spotted a rare red-crested pochard, reported the sighting and was initially doubted. Only when the bird was shot by a hunter and confirmed by a museum did the young birder’s reputation rise. For Mayr, the lesson was not that he had been right, but that careful observation and documentation could change minds. In retrospect, it prefigured his later insistence that species are not abstract categories but real populations, living and changing in particular places.

By the time he was invited to the United States to work at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in 1931, the outlines of his big questions were set. How do new species arise? Are they sharply separated kinds, as older “typological” biology assumed, or products of continuous variation across geography and time? Those questions would drive the core of the Ernst Mayr biography for the next seven decades.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Ernst Mayr

The biological species concept theory

Mayr’s most famous contribution, and one that appears in almost every account of his legacy, is the “biological species concept”. In his 1942 book Systematics and the Origin of Species, written while at AMNH, he argued that a species is not simply a group of organisms that look alike. It is a population – or set of populations – whose members actually or potentially interbreed with one another and are reproductively isolated from other such groups.

This might sound technical, but it solved a long-standing puzzle: why species seem both real and fuzzy. By tying species to reproductive communities, Mayr shifted the focus from static “types” to dynamic populations. The idea reshaped evolutionary theory and remains a cornerstone in textbooks, even though biologists still argue over how to apply it in messy real-world cases like bacteria or ring species.

Architect of the modern evolutionary synthesis

In the 1930s and 1940s, a small group of thinkers – including Theodosius Dobzhansky, Julian Huxley, George Gaylord Simpson and G. Ledyard Stebbins – blended Darwin’s natural selection with Mendelian genetics and population thinking. Mayr was central to this modern evolutionary synthesis, bringing the perspective of the field naturalist and systematist.

Where geneticists worked with fruit flies in bottles, Mayr worked with finches, warblers and birds of paradise across continents and archipelagos. His message was simple but powerful: evolution happens in populations, in real places, shaped by geography, migration and reproductive barriers. That conviction, hammered home in works such as Animal Species and Evolution and later essays, made him one of the great discipline-builders of 20th-century science.

Peripatric speciation and the founder effect

Mayr also popularised the idea of peripatric speciation – a refined form of allopatric speciation in which small, isolated populations at the edge of a species’ range undergo rapid genetic change and split off as new species. He argued that when just a few colonists arrive on an island or remote patch of habitat, chance “founder effects” and intense natural selection can accelerate evolutionary divergence.

Decades later, experiments on lizards marooned on tiny Adriatic islands would be framed explicitly in terms of testing Mayr’s founder-effect speciation ideas – a reminder that the theories emerging from his fieldwork and synthesis were still shaping research well into the 21st century.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

How the Ernst Mayr biography reveals a working naturalist

The Ernst Mayr biography is, in part, a study in how a certain kind of scientist works. Mayr was, first and last, a naturalist. His method began with meticulous observation: measuring beaks, mapping ranges, paying attention to behaviours that might signal barriers to mating or dispersal. He valued long series of specimens, not as trophies, but as snapshots of variation over space and time.

At the American Museum of Natural History in New York, Mayr combined this old-fashioned natural history with new statistical and genetic tools. He organised seminars at the Linnean Society of New York, mentored young birders who would go on to become scientists in their own right and turned the museum into a hub of evolutionary biology pioneer work.

Harvard years and the Museum of Comparative Zoology

In 1953, Mayr moved to Harvard University as Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology and soon took over as director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), a post he held from 1961 to 1970. During those years, he not only expanded collections and staff but also helped shape the MCZ Library that now bears his name. Today, the Ernst Mayr Library of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard preserves his papers, correspondence and an extensive bibliography of his writings, making it a key resource for anyone exploring his life and work.

Harvard colleagues recall him as both courtly and fiercely opinionated, someone who could be withering in debate but generous with time and advice. Profiles by science writers have described him as “the Darwin of the 20th century” and “a living archive of biology”, a man who had seen the field change from expedition-driven taxonomy to molecular biology and genomics, and still had strong views about what mattered.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Beanbag genetics and the limits of reductionism

Mayr was never shy about criticising colleagues. One of his most famous jabs was at early mathematical population genetics, which he dismissed as “beanbag genetics” – too focused on changes in individual genes and not enough on whole organisms and real populations in nature.

The phrase stuck, and so did the argument. While modern evolutionary biology uses sophisticated models and molecular tools, many researchers still echo Mayr’s insistence that biology is not just physics plus chemistry; it is a historical science with its own concepts and levels of explanation. In his essays on the autonomy and philosophy of biology, Mayr argued that attempts to fully reduce life to physics had, in his view, failed.

Race, typology and the Ernst Mayr biography in the 21st century

In recent years, a new controversy has touched the Ernst Mayr biography. Scientific societies have debated whether prizes named after him should be renamed, citing worries about past views on race and eugenics. The re-examination comes at a time when many institutions are scrutinising the racial attitudes of 20th-century scientists.

The picture that emerges from historians is complex. On the one hand, Mayr came of age in a Europe where racial typologies were common; on the other, he spent much of his career dismantling the very idea of fixed “types” in biology. His advocacy of “population thinking” – the view that variation within species is fundamental, and that sharp racial categories are scientifically misleading – has been cited by some as a powerful tool against scientific racism.

These debates do not erase his scientific achievements, but they do show how any serious Ernst Mayr biography today must grapple with both his role as a 20th-century science pioneer and the evolving ethical standards by which we judge that history.

Impact on Evolutionary Biology and on Wider Society

Shaping how we talk about species

Mayr’s influence on evolutionary theory is easiest to see in how biologists talk about species. The idea that species are “metapopulation lineages” – evolving lineages of populations connected by gene flow – owes much to his biological species concept and to debates he helped frame. Even where researchers reject his exact definition, they usually do so in conversation with his work.

For conservationists, the questions Mayr raised remain urgent. Should a slightly different island form of a bird be managed as a distinct species, deserving its own protection, or treated as a regional variant? How we answer such questions affects laws, funding and even which habitats are saved from destruction.

Influence on public debates about evolution

Beyond academia, Mayr’s books and essays shaped broader cultural debates about evolution. Works such as The Growth of Biological Thought explored how the Darwinian revolution transformed not just biology but philosophy and theology, insisting that an evolving world left less room for fixed purposes and human exceptionalism.

His public comments, whether on the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (which he doubted would succeed) or on creationism, often made headlines and sparked discussion. For journalists and commentators writing about evolution in the late 20th century, citing Ernst Mayr became a shorthand for calling on the dean of evolutionary biology.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Family life behind the lab door

Away from lectures and seminars, Mayr’s private life was quieter. In 1935 he married Margarete “Gretel” Simon, a fellow German he had met in New York. The couple had two daughters and remained together until her death in 1990. Colleagues recall the Mayr household in Massachusetts as simultaneously European and American: strong coffee, precise manners, and a steady flow of students and visiting scientists.

He lived simply, devoted to his work but also to long walks and birdwatching well into old age. On his 100th birthday he gave interviews reflecting on a life in science, displaying both sharp memory and the bluntness of someone who had long ceased to worry about ruffled feathers.

Belief, atheism and ethics

On questions of religion, Mayr was clear-eyed and unapologetic. He described himself as an atheist with respect to a personal God, arguing that there was no evidence to support such a being and that evolutionary biology offered a powerful, naturalistic account of apparent design in nature.

Yet he was not a nihilist. His essays on “evolution and ethics” argued that moral systems arise from human social life and evolutionary history, not from divine command. In that sense, the Ernst Mayr biography is part of a broader 20th-century story: scientists wrestling with what it means to live in a world where humans are one evolved species among many.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Ernst Mayr

Writing into his nineties

One of the most striking facts in any Ernst Mayr biography is how productive he remained late in life. After retiring from Harvard in 1975, he continued to publish prolifically. Of his 25 books, more than half appeared after he turned 65; he kept writing well into his nineties, tackling everything from the philosophy of biology to the history of Darwinism.

This late-life productivity was not mere tidying up. Mayr used it to push arguments he felt had been misunderstood – stressing, for example, the importance of historical explanation in biology and the difference between proximate (mechanistic) and ultimate (evolutionary) causes. Generations of students encountered evolution not only through Darwin but through Mayr’s essays and textbooks.

Honours and the absence of a Nobel Prize

Over his career, Mayr accumulated scientific honours: the National Medal of Science, the Balzan Prize, the Crafoord Prize (sometimes called a “Nobel for biology”), the International Prize for Biology and many others. He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society and honoured by societies across the world. That he never received a Nobel Prize amused rather than embittered him; he liked to point out that there is no Nobel for evolutionary biology and that even Darwin would not have qualified.

Mayr died on 3 February 2005, aged 100, in a retirement community in Bedford, Massachusetts, after a short illness. Obituaries in major newspapers hailed him as a “seminal evolutionist” and “Darwin’s heir”, noting that his ideas had made the very notion of species central to modern biology. A detailed Washington Post obituary on Ernst Mayr emphasised how he connected Darwin’s theories with modern genetics and helped create the field of evolutionary biology.

The Lasting Legacy of Ernst Mayr biography

A template for evolutionary thinking

What, then, is the lasting legacy of the Ernst Mayr biography? At the most basic level, it is a set of ideas: that species are real, evolving populations; that geography and reproductive isolation are key to understanding biodiversity; that biology has its own concepts and cannot be fully reduced to physics; and that population thinking, not typology, is the proper way to understand variation in nature.

Those ideas continue to shape everything from conservation policy to the way we talk about human variation. When journalists today write about debates over speciation or the meaning of race, they are, often unknowingly, writing in a conceptual landscape that Mayr helped to build.

Where his influence still shows up

You can see traces of his work in experimental studies of founder effects on island lizards, in legal arguments over which endangered frogs count as distinct species, and in philosophical debates about whether biology can ever be a completely “unified” science. You can even see it in the way young scientists are trained: moving comfortably between genes and field observations, between statistical models and natural history notes.

For readers today, understanding the Ernst Mayr biography means more than learning about one distinguished scientist. It means seeing how modern evolutionary biology came to be – and recognising that our current arguments about biodiversity, race, human nature and the future of life on Earth all unfold in a world shaped by his questions and his answers.

Frequently Asked Questions about Ernst Mayr biography

Q1: Who was Ernst Mayr, in simple terms?

Q2: Why is the Ernst Mayr biography often linked to the phrase ‘Darwin of the 20th century’?

Q3: What is Ernst Mayr’s biological species concept?

Q4: How did Ernst Mayr influence modern evolutionary biology beyond species definitions?

Q5: Was Ernst Mayr involved in controversies about race and human variation?

Q6: Where can I read more detailed scientific discussion related to the Ernst Mayr biography?