On a late-summer morning in 1928, in a cramped London laboratory piled high with forgotten petri dishes, a quiet Scotsman noticed that one of his bacterial cultures had gone wrong. A stray mould had crept across the plate – and, in a thin halo around it, the bacteria were dead. That moment, now retold in every Alexander Fleming biography, has become one of the founding stories of modern medicine. It marks the beginning of the antibiotic age, and with it a dramatic shift in humanity’s long fight against infection.

Yet the real Alexander Fleming biography is not just about a lucky spill of spores. It is the tale of a farmer’s son who became a meticulous hospital doctor, a First World War officer horrified by festering wounds, and a patient observer of tiny details that others missed. It is also a story about how scientific credit is shared – or not – and about the uneasy legacy of antibiotics in a world now wrestling with drug-resistant “superbugs”.

Alexander Fleming at a glance

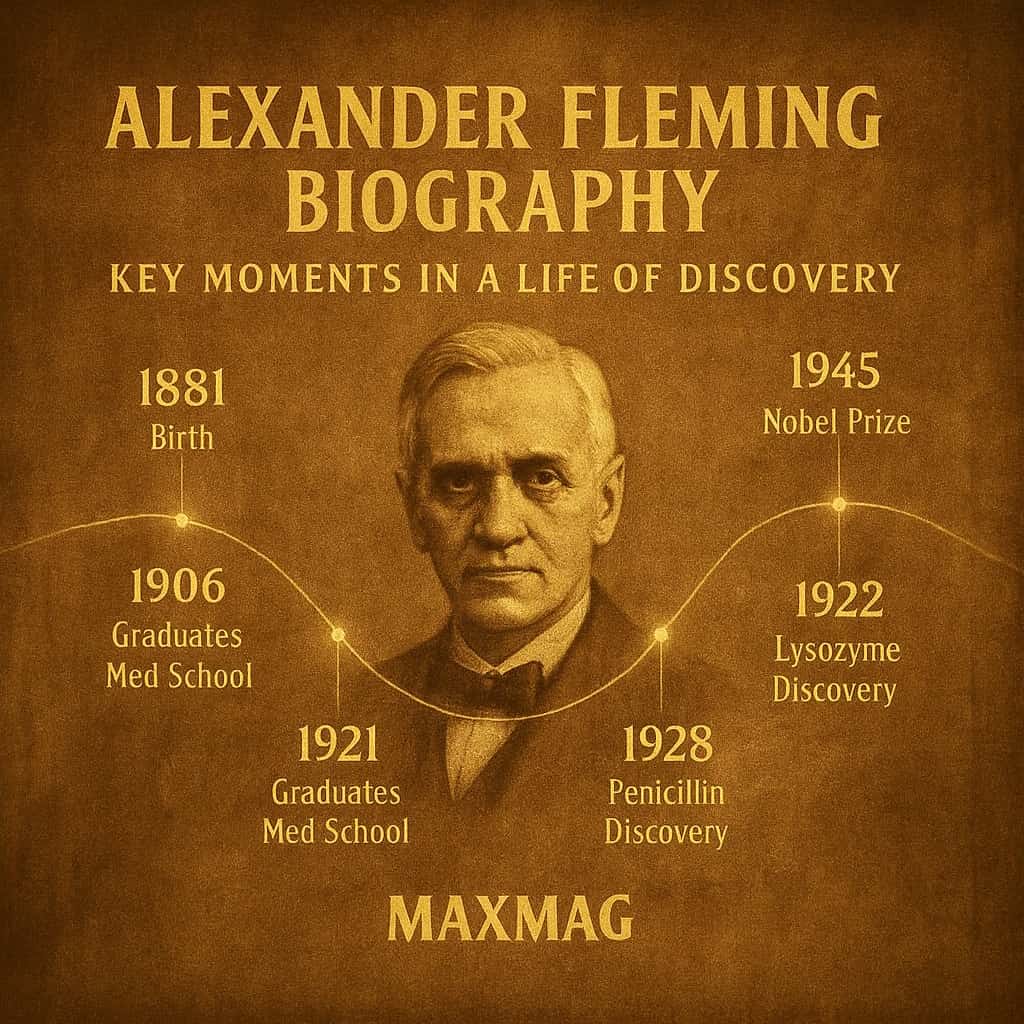

- Who: Scottish physician and microbiologist, best known for discovering the antibiotic substance penicillin in 1928.

- Field and era: Bacteriology and immunology in early–mid 20th century medicine.

- Headline contributions: Discovery of lysozyme and penicillin; Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1945, shared).

- Why he matters today: His work launched the antibiotic revolution, reshaping medical history and still influencing public health debates worldwide.

Early Life and Education of Alexander Fleming

The rural childhood behind every Alexander Fleming biography

Alexander Fleming was born in 1881 at Lochfield farm near Darvel in Ayrshire, Scotland, the seventh of eight children in a blended family. Life on the farm was demanding but close to nature: animals, muddy fields and the constant risk of minor injuries and infections formed the background to his childhood. The contrast between robust country health and the sudden danger of sepsis would later echo through his medical work, even if he rarely spoke about it in public.

From shipping office to medical school

Fleming was not the sort of child prodigy who seems destined from birth to change history. After school he moved to London and found work in a shipping office, a routine clerical job that might easily have become a lifelong career. But a small inheritance from an uncle opened another path. Encouraged by an older brother who was already a doctor, Fleming sat the entrance exam for St Mary’s Hospital Medical School in London – and passed with ease. It was a quiet turning point in the Alexander Fleming biography, the moment he stepped from office ledgers into dissecting theatres.

Training in a city of infections

London at the turn of the 20th century was a city of crowded tenements, soot-blackened air and frequent outbreaks of infectious disease. As a medical student, Fleming saw up close how easily patients died from conditions that today seem trivial: infected cuts, postpartum fever, pneumonia. Even a grazed knee could lead to a fatal blood infection. These experiences, reinforced by his early work with bacteriologist Almroth Wright at St Mary’s, pushed him towards the then-new field of bacteriology, the study of disease-causing microbes.

By the time he qualified in 1906, Fleming had already developed a reputation for technical skill and calm steadiness in the lab. His teachers noticed his ability to see patterns in scattered results, a habit of mind that would later define the Alexander Fleming biography as much as the legendary “accident” on his bench.

Alexander Fleming biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

A wartime turning point in the Alexander Fleming biography

When the First World War broke out, Fleming served as a captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps, treating wounded soldiers in makeshift hospitals in France. The horrors he saw there never quite left him. Even when surgeons operated quickly and cleanly, men often died days later from infections seeded deep in their wounds. The antiseptics of the time – powerful chemicals poured into tissue – sometimes did more harm than good, damaging the body’s own defences while barely touching microbes buried in dead flesh.

After the war, back at St Mary’s, Fleming became obsessed with finding gentler ways to fight bacteria. In 1921 he discovered lysozyme, an enzyme present in tears, saliva and mucus that dissolves the cell walls of certain microbes. It was not the universal germ killer he hoped for, but it showed that the body itself produced natural antibacterial substances. For any careful reader of an Alexander Fleming biography, lysozyme is the dress rehearsal for penicillin – a first glimpse of nature’s own pharmacy.

The messy lab that made medical history

Fleming’s laboratory at St Mary’s Hospital has passed into scientific folklore. Colleagues later described benches piled high with petri dishes and cultures left to sit far longer than standard protocols allowed. This apparent untidiness was, in a way, his method. He liked to let bacterial plates incubate for weeks, hoping that something unexpected would happen on the smooth jelly surface. The future hero of medical history was not seeking a tidy experiment; he was watching for anything that broke the rules.

The petri dish that changed everything

In September 1928, returning from a holiday, Fleming began clearing away some old plates smeared with Staphylococcus bacteria, common culprits in wound infections. On one dish he noticed an odd scene: a patch of greenish mould, and around it a clear zone where the bacteria had vanished. Many accounts of the Alexander Fleming biography linger on this moment – the scientist staring at a plate he might easily have thrown away. Instead he kept it, isolated the mould and identified it as belonging to the Penicillium genus. He called the antibacterial substance it produced “penicillin”.

In simple terms, Fleming had stumbled on a fungus that secreted a chemical weapon against bacteria. The idea itself was not entirely new – doctors had long suspected that some microbes attacked others – but here was a clear, visible example. It was as if, in a crowded city of germs, he had discovered that one neighbourhood was mysteriously uninhabitable, poisoned by its own residents.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Alexander Fleming

Lysozyme: the first glimpse of nature’s disinfectant

Years before penicillin, Fleming published careful work on lysozyme, the antibacterial enzyme he found in his own nasal mucus and in egg whites, tears and human saliva. Lysozyme attacks the outer walls of certain bacteria, causing them to burst. While it turned out to be more effective against relatively harmless microbes than against serious pathogens, the research showed that the human body is constantly performing its own microscopic housekeeping, washing away potential invaders with built-in defences. This theme – nature as chemist and doctor – runs throughout every thoughtful Alexander Fleming biography.

Penicillin at the heart of any Alexander Fleming biography

Fleming’s brief 1929 paper describing penicillin was cautious but clear. He showed that the substance was non-toxic to animal cells yet lethal to many disease-causing bacteria, including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. He suggested it might be useful for treating infections and for cleaning up bacterial contamination in the lab. What he did not do was turn penicillin into a practical drug. He lacked both the chemical expertise and the industrial backing to purify the compound on a large scale, and his early samples were unstable and weak. For years, penicillin remained a promising curiosity, not a medicine.

Sharing credit in the antibiotic revolution

In the late 1930s, a research team at Oxford led by Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain revisited Fleming’s work. They devised methods to grow the mould in bulk, extract and stabilise penicillin, and test it in animals and humans. Their efforts turned a fragile laboratory observation into a usable antibiotic that could be produced in factories. When Fleming, Florey and Chain shared the Nobel Prize in 1945, it underlined a central theme of any honest Alexander Fleming biography: great medical breakthroughs are rarely the work of a lone genius, but of networks of scientists, clinicians and industrial partners spread across countries and years.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

A quiet eye for the unusual

Fleming was not a flamboyant lecturer or a charismatic public figure. Colleagues described him as reserved, almost shy, with a dry sense of humour and a tendency to let others argue while he watched. His gift lay in noticing small anomalies – a single odd plate among dozens, a pattern of response that did not fit expectations – and refusing to ignore them. In that sense, the Alexander Fleming biography is a case study in the power of curiosity over routine, of someone who allowed himself to be interested in what most people would have scraped into the bin.

St Mary’s and the culture of bacteriology

At St Mary’s, Fleming belonged to a tight-knit group of bacteriologists around Almroth Wright. The lab combined clinical work for the hospital with fundamental research. They developed vaccines, studied immune responses and advised on infection control. This environment suited Fleming’s practical temperament. He was never content with abstract theory alone; he wanted to see how findings could be applied at the bedside, from cleaning wounds to preventing post-operative infections.

Team efforts and tension over fame

When penicillin finally became a viable drug during the Second World War, the collaboration between British and American laboratories was essential. Industrial chemists in the United States, using deep-tank fermentation, learned to grow Penicillium mould in huge quantities, dramatically increasing yields. An Alexander Fleming biography that focuses only on the London petri dish misses this more complex picture: a web of wartime urgency, government funding and international science policy. Fleming himself was sometimes uncomfortable with the scale of the credit he received, aware that others had done the heavy lifting of development, even as public attention fixed almost entirely on his “accidental” discovery.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

The myth of pure luck in the Alexander Fleming biography

Popular retellings often present Fleming as a lucky man who left his lab in a mess, came back from holiday and stumbled upon penicillin. There is truth in the story – chance clearly played a role – but it is only half the picture. Many scientists see unexpected results every day; most do not pause long enough to ask what they mean. Fleming did. The real lesson of the Alexander Fleming biography is not that accidents happen, but that trained, curious minds can recognise the significance of those accidents.

Who really “discovered” penicillin?

Another debate centres on the division of credit between Fleming and the Oxford team. Some historians argue that calling Fleming the “discoverer of penicillin” oversimplifies the process, since Florey, Chain and their colleagues turned a laboratory observation into a medicine that could be injected into patients and manufactured at scale. Others point out that without Fleming’s initial paper and his preserved strain of mould, the Oxford group might never have started. The Nobel Prize committee’s decision to honour all three reflects the complicated reality of scientific discovery and the broader history of medicine.

Antibiotic resistance and unintended consequences

Fleming himself warned, in later speeches, that careless use of antibiotics could breed resistant bacteria. He imagined patients who stopped their courses early or doctors who prescribed penicillin too freely, allowing partially resistant microbes to survive and spread. Decades on, those warnings feel prophetic. A serious Alexander Fleming biography must therefore grapple with the shadow side of the antibiotic revolution he helped launch: a world where once-miraculous drugs are losing their power, and where public health agencies now speak of a “post-antibiotic era” as a real possibility.

Impact on Medicine and on Wider Society

From fatal infections to treatable illnesses

Before antibiotics, many everyday medical procedures – from childbirth to minor surgery – carried a substantial risk of death from infection. Penicillin transformed that landscape. Suddenly, doctors could treat bacterial pneumonia, blood poisoning and wound infections with a drug that targeted microbes rather than the patient’s tissues. Mortality rates for previously lethal conditions plummeted. As one detailed chemical history of penicillin notes, this was not a small incremental advance but a step-change in the practice of medicine, opening the door for countless later antibiotics and complex surgeries that would have been unthinkable in Fleming’s youth.detailed history of penicillin’s development

War, peace and the promise of antibiotics

The first large-scale use of penicillin came during the Second World War, when Allied forces deployed it to treat wounded soldiers. The drug saved countless lives on the battlefield and in military hospitals, reshaping the statistics of war casualties. In peacetime, antibiotics enabled safer childbirth, cancer chemotherapy and organ transplantation. The Alexander Fleming biography is thus woven into the broader history of 20th century science and technology, where new drugs, vaccines and public health measures combined to extend life expectancy dramatically.

Public hero, private scientist

As news of penicillin’s success spread, Fleming became a reluctant celebrity. Newspapers and magazines, especially in the United States, cast him as the archetypal lone genius who changed the world by accident. A widely read profile in a major American weekly, for instance, retold the story as a chain of improbable events leading from one cluttered London bench to a global medical revolution.Time magazine’s account of Fleming’s discovery The resulting public image sometimes sat uneasily with the more nuanced reality cherished by historians of medicine and by colleagues who knew how many other hands were involved.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

A reserved man in the spotlight

Friends and colleagues often described Fleming as modest, even self-effacing. He preferred the controlled world of the laboratory to the glare of public ceremonies. Photographs from the height of his fame show a slightly stooped man in a lab coat, more at ease among flasks and microscopes than on a podium. This human dimension is crucial to any Alexander Fleming biography: he did not seek the status of “saviour of millions”, yet he accepted the honours that came with his discovery, from a knighthood to honorary degrees around the world.

Family life and companionship

Fleming married nurse Sarah Marion McElroy in 1915, during the First World War. They had one son, Robert, who went on to become a general practitioner. After Sarah’s death in 1949, Fleming eventually remarried, this time to Dr Amalia Koutsouri-Vourekas, a Greek colleague from St Mary’s. Those who knew him remarked that the second marriage brought renewed warmth and energy into his life. The Alexander Fleming biography, often dominated by lab stories, is also a story of companionship built around shared medical work and long hours on the wards.

Habits, hobbies and quiet passions

Away from the bench, Fleming enjoyed painting, particularly with bacteria that produced different colours, turning petri dishes into unusual artworks. This playful side – a bacteriologist making “germ paintings” – hints at a creativity that ran in parallel with his rigorous science. He also kept a modest country home in Suffolk, relishing periods of quiet away from London. These glimpses of private life help round out the portrait of a man who, to many patients, existed only as a name on a medicine bottle.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Alexander Fleming

From researcher to elder statesman of medicine

After the Nobel Prize in 1945, Fleming’s daily work changed. He continued to publish scientific papers and to supervise research, but he also became a sort of ambassador for the new antibiotic era, travelling widely to lecture about penicillin and the promise of microbiology. Universities and medical societies queued up to award him honours. For some observers, the later chapters of the Alexander Fleming biography are tinged with irony: the quiet lab man transformed into a symbol, his image simplified even as scientific understanding of antibiotics grew more complex.

Warning the world about misuse

In public speeches, Fleming repeatedly stressed that penicillin was not a magic bullet to be used without care. He described an imaginary patient who took too little of the drug, killing off the weakest bacteria but allowing hardier, resistant strains to survive. This, he warned, would create infections that penicillin could no longer cure. His cautionary words are now quoted frequently in discussions of antibiotic stewardship, underlining how this Alexander Fleming biography intersects with today’s urgent debates on global health policy and responsible prescribing.

Death and resting place

On 11 March 1955, Fleming died of a heart attack at his London home, aged 73. His ashes were interred in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, close to national heroes such as Nelson and Wellington – an extraordinary resting place for a farmer’s son who once worked in a shipping office. The setting is a reminder of how profoundly his work changed British and global society: an acknowledgement that the quiet war against microbes can be as consequential as battles fought with guns and ships.

The Lasting Legacy of the Alexander Fleming biography

How penicillin reshaped the story of disease

Today, penicillin and its descendants remain among the most widely used antibiotics in the world. They have saved hundreds of millions of lives, turned terrifying illnesses into routine clinical problems and enabled everything from intensive care medicine to complex surgery. Any serious Alexander Fleming biography must wrestle with this scale of impact: a single insight in a small London lab reverberating through maternity wards, operating theatres and emergency rooms across the planet.

From hero story to shared responsibility

Modern historians increasingly place Fleming alongside the many other figures who contributed to the antibiotic era – laboratory technicians, industrial chemists, nurses, policymakers and patients themselves. This broader perspective does not diminish Fleming; instead, it enriches the Alexander Fleming biography, showing how individual curiosity interacts with institutions, funding, and the wider currents of 20th century science. Understanding that interplay helps explain why some discoveries lead to social transformation while others remain footnotes.

Why the Alexander Fleming biography still matters now

In an age of rising antibiotic resistance, returning to the Alexander Fleming biography is more than a tribute to past glory. It is a way of thinking about how we discover, develop and use powerful tools against disease. Fleming’s story reminds us that breakthroughs often come from paying attention to the unexpected, that scientific fame rarely captures the whole cast of contributors, and that every new drug carries responsibilities as well as benefits. To understand the journey from a mouldy petri dish to a world struggling with superbugs is to understand something essential about modern medicine itself.

Frequently Asked Questions about Alexander Fleming biography

Q1: What is the central achievement highlighted in an Alexander Fleming biography?

Q2: Did Alexander Fleming work alone on penicillin?

Q3: How does an Alexander Fleming biography usually describe his personality?

Q4: Why is Alexander Fleming important to medical history?

Q5: What role does antibiotic resistance play in the Alexander Fleming biography today?

Q6: Where is Alexander Fleming buried, and why is that significant?