In the middle of the 19th century, when doctors still blamed “bad air” and moral weakness for many illnesses, one meticulous French chemist was quietly dismantling the old certainties. The Louis Pasteur biography is not just the story of a brilliant mind; it is the story of how invisible organisms, once dismissed as scientific curiosities, became the central characters in our understanding of disease.

Today, every time milk is pasteurised, vaccines are delivered, or surgeons scrub their hands before an operation, traces of this life’s work are still in motion. The Louis Pasteur biography is part detective story, part industrial rescue mission, and part ethical drama about risk, ambition and public trust. It is also, in many ways, the story of how modern microbiology, public health and vaccination were born.

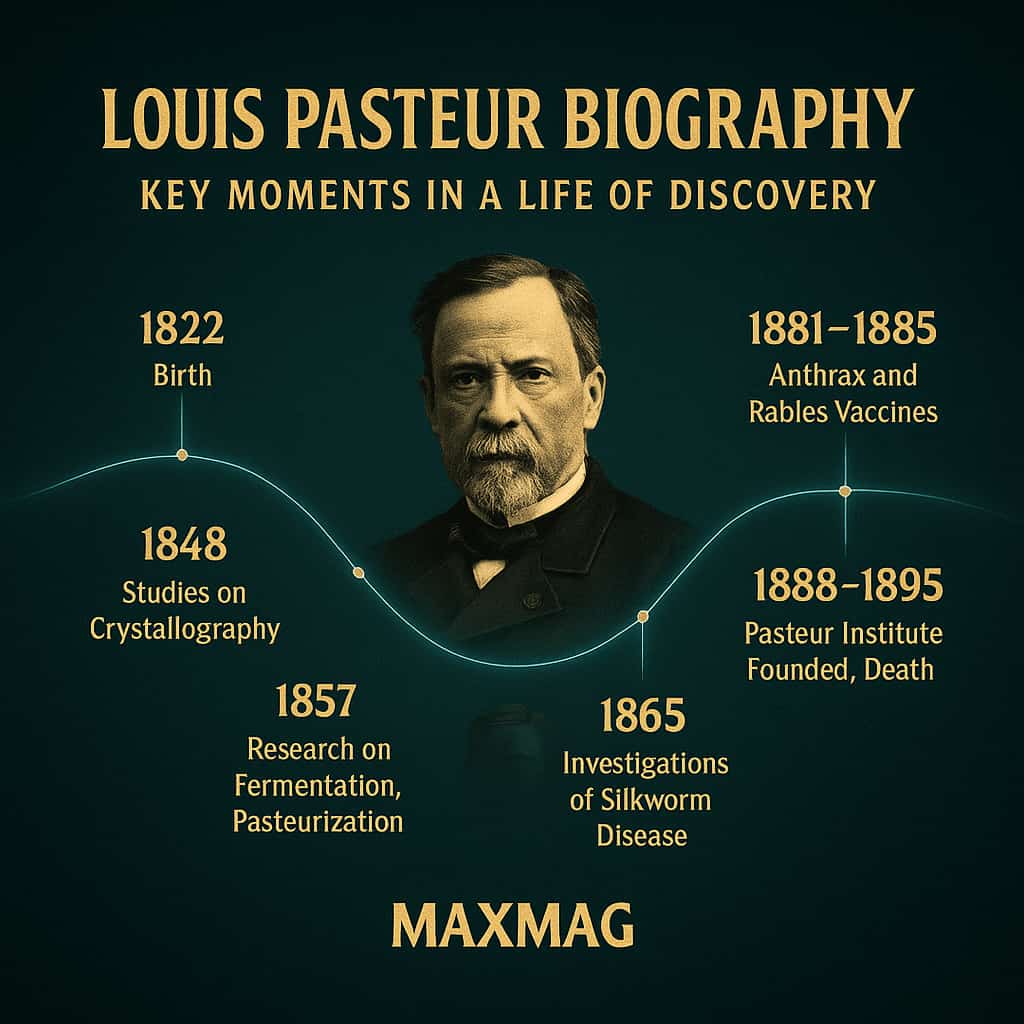

Louis Pasteur at a glance

Before diving into the details of the Louis Pasteur biography, it helps to see the outline of his life in one frame.

- Who: Louis Pasteur, French chemist and microbiology pioneer.

- When: 1822–1895, in the turbulent era of 19th-century science and industrialisation.

- Known for: Germ theory of disease, pasteurisation, vaccines for anthrax and rabies, and founding the Pasteur Institute.

- Why he matters today: His work underpins modern infection control, vaccine development and the basic idea that microbes cause diseases—and can be controlled.

With that snapshot in mind, the deeper layers of the Louis Pasteur biography become easier to follow: the late-blooming student, the painstaking experimentalist, the patriotic Frenchman, and the controversial figure whose notebooks would later be used to question his methods.

Early Life and Education of Louis Pasteur

A tanner’s son in provincial France

Louis Pasteur was born in 1822 in the small town of Dole in eastern France, the son of a former soldier turned tanner. His childhood was closer to the rhythms of craft and small-town life than to the laboratories he would later dominate. The young Pasteur was not a prodigy in the classroom. Teachers noted his diligence rather than brilliance, and his early talent seemed to lie in portrait drawing rather than in mathematics or chemistry.

This is one of the first surprises in the Louis Pasteur biography: the “father of microbiology” began life as a perfectly ordinary pupil, more interested in sketching the faces of friends and neighbours than in solving equations. It was only in his late teens that science began to exert a serious pull.

From hesitant pupil to committed scholar

Pasteur’s academic record improved steadily at secondary school. Encouraged by teachers who recognised his growing focus, he moved from provincial colleges to Paris, where the intellectual climate was sharper, the competition tougher and ambition almost a requirement. Even then he suffered setbacks, including periods of homesickness so intense that he briefly returned home.

The turning point in the Louis Pasteur biography came when he entered the École Normale Supérieure, one of France’s elite training grounds for teachers and researchers. There he specialised in chemistry and physics, absorbing both rigorous theory and the hands-on experimental traditions that would define his later work.

By the time he completed his doctoral work on the structure of crystals, the late-blooming student had become a precise and ambitious young scientist at the edge of a new scientific era.

The Louis Pasteur biography and the birth of his big ideas

From portrait artist to chemist of the invisible

In his early research, Pasteur did not set out to revolutionise medicine. He worked on tartrates—crystals derived from tartaric acid—trying to understand why some samples rotated polarised light in different directions. The problem seemed obscure, but his solution quietly cracked open a new dimension of matter: molecular asymmetry.

Pasteur noticed that the crystals, though chemically identical, came in mirror-image forms. By painstakingly separating them, he showed that this “handedness” explained their different behaviour with light. That work laid the foundations of stereochemistry, convincing him that small, invisible differences could have enormous consequences.

In the Louis Pasteur biography, this episode is more than an early success. It is a clue to his scientific temperament: obsessive attention to detail, a willingness to spend long hours on a seemingly minor problem, and a growing conviction that unseen structures could govern the visible world.

How the Louis Pasteur biography became a story of germ theory

The step from crystals to microbes was not as big as it might seem. In both cases, Pasteur was trying to understand invisible agents with visible effects. His work on fermentation—why grape juice became wine, or milk turned sour—pushed him towards the idea that microscopic organisms, not vague “vital forces”, were responsible.

At the time, many scientists believed in spontaneous generation: the idea that life could arise from non-living matter, as maggots supposedly appeared from rotting meat. Pasteur designed a series of elegant experiments using swan-neck flasks, showing that boiled broth remained sterile unless exposed to airborne particles. In doing so, he advanced germ theory history and demonstrated that microbes came from other microbes, not from nowhere.

This scientific turning point in the Louis Pasteur biography transformed him from promising chemist into a central figure of 19th-century science, and set the stage for his later role as a microbiology pioneer.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Louis Pasteur

Fermentation, wine and the rescue of French industry

If the Louis Pasteur biography were only about laboratory theory, it would still be impressive. But his work was rooted in very practical problems. In the 1860s, French wine and beer producers faced serious economic threats: their products were spoiling unpredictably, turning sour and undrinkable. Pasteur was asked to help.

Studying samples under the microscope, he found that different kinds of microorganisms were associated with different outcomes. Healthy fermentation had one microbial signature, while spoiled wine showed another. By heating wine or beer to a carefully chosen temperature for a set time, he could kill the unwanted microbes without ruining the flavour. This process—pasteurisation—would later be applied to milk and many other foods, quietly protecting millions of people from food-borne diseases.

These industrial interventions cemented his reputation not only as a scientist, but as a saviour of national industries. Here, the Louis Pasteur biography becomes a story of economic as well as scientific rescue.

Germ theory, silkworms and agricultural crises

Pasteur’s ability to move between the laboratory and the field was tested again when French silk production was threatened by disease in silkworms. Rather than treating this as a niche agricultural issue, he applied the same logic he had used in fermentation: somewhere, microscopic agents were at work.

After painstaking investigation, he identified parasitic infections as the culprits and developed methods to select healthy eggs, helping to save another sector of the French economy. Once again, germ theory history is not abstract: it is written in the survival of vineyards and silk farms as much as in medical textbooks.

Vaccines, anthrax and rabies

The path from understanding germs to controlling them took Pasteur into the heart of vaccine development. He learned that by exposing animals to weakened forms of disease-causing microbes, he could prime their bodies to resist later infection. He applied this principle to chicken cholera and anthrax, demonstrating that vaccination could protect flocks and herds.

Anthrax posed a particularly visible challenge, killing livestock across Europe. Pasteur staged public experiments, vaccinating one group of sheep and leaving another unprotected. When both groups were exposed to anthrax, the unvaccinated animals died while the vaccinated survived, a dramatic demonstration that helped convince a sceptical public and solidified his vaccine pioneer status.

His most famous and ethically fraught achievement came with the rabies vaccine. In 1885, a nine-year-old boy, Joseph Meister, was brought to Pasteur after being savaged by a rabid dog. Pasteur, who was not a licensed physician, faced an agonising choice. After testing his new vaccine on animals, he decided—with physicians present—to treat the child. Meister survived, and the episode became one of the most dramatic chapters in the Louis Pasteur biography, a case where scientific daring and medical ethics collided in real time.

For readers wanting a structured overview of his discoveries, the Lemelson-MIT profile of Louis Pasteur offers a concise, research-based summary of his major breakthroughs and their impact on modern microbiology.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

A crowded laboratory and demanding leader

Pasteur’s laboratory was not a quiet, solitary place. It was a busy, sometimes chaotic environment filled with glassware, animals, assistants and visiting dignitaries. He was a hands-on director, closely involved in designing experiments and interpreting results, yet increasingly reliant on younger colleagues as illness and age took their toll.

Accounts from those who worked with him describe a demanding mentor with a fierce sense of purpose. He expected long hours, careful note-taking and loyalty to the project. This intensity helped drive the success of his research programme but also contributed to tensions, particularly when credit for discoveries was at stake.

The Louis Pasteur biography as a story of teamwork

One of the risks of focusing too much on a single heroic figure is that it obscures the network of collaborators who make large scientific projects possible. The Louis Pasteur biography is, in fact, threaded through with the names of assistants and colleagues: Émile Roux, who played a critical role in vaccine development; Charles Chamberland, who helped design filtration devices; and many others who translated broad ideas into workable experiments.

Recognising this teamwork does not diminish Pasteur as a microbiology pioneer. Instead, it places him in a more realistic history of science, where breakthroughs emerge from intense collaboration, disagreement and collective effort rather than from a lone genius working in isolation.

In this sense, the Louis Pasteur biography is also a study in how laboratories became modern institutions, with hierarchies, specialisations and shared credit—sometimes fairly allocated, sometimes not.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Hero, strategist, or something in between?

For much of the 20th century, the Louis Pasteur biography was told as a straightforward heroic tale: a virtuous scientist battling ignorance and disease. But from the 1990s onward, historians began to revisit this image, especially when Pasteur’s private laboratory notebooks were published and compared with his public accounts.

The historian Gerald L. Geison argued that Pasteur sometimes simplified or re-sequenced events to make his experiments appear more decisive than they really were, particularly in the case of the anthrax vaccine. Others accused him of downplaying the contributions of rivals and predecessors.

Critics saw this as evidence of a more calculating, competitive figure, while defenders argued that such narrative shaping was common in 19th-century science, where national pride and institutional support were always in play.

Contested experiments in the Louis Pasteur biography

Some of the sharpest debates have centred on the details of his vaccine trials. Did he really use the method he claimed for the anthrax vaccine in public demonstrations? Did he move ahead with human trials for rabies more quickly than was ethically justified? These questions have turned the Louis Pasteur biography into a case study in scientific ethics.

A widely read analysis in PBS’s coverage of Pasteur’s rabies experiment walks through the risks he took and the limited options available to the terrified family in 1885, showing how historical context complicates easy moral verdicts.

These controversies do not erase his achievements, but they do add texture. The Louis Pasteur biography becomes not a simple morality play, but a more human story about ambition, uncertainty and the pressure to deliver dramatic results in an era of high public expectation.

Impact on Microbiology and on Wider Society

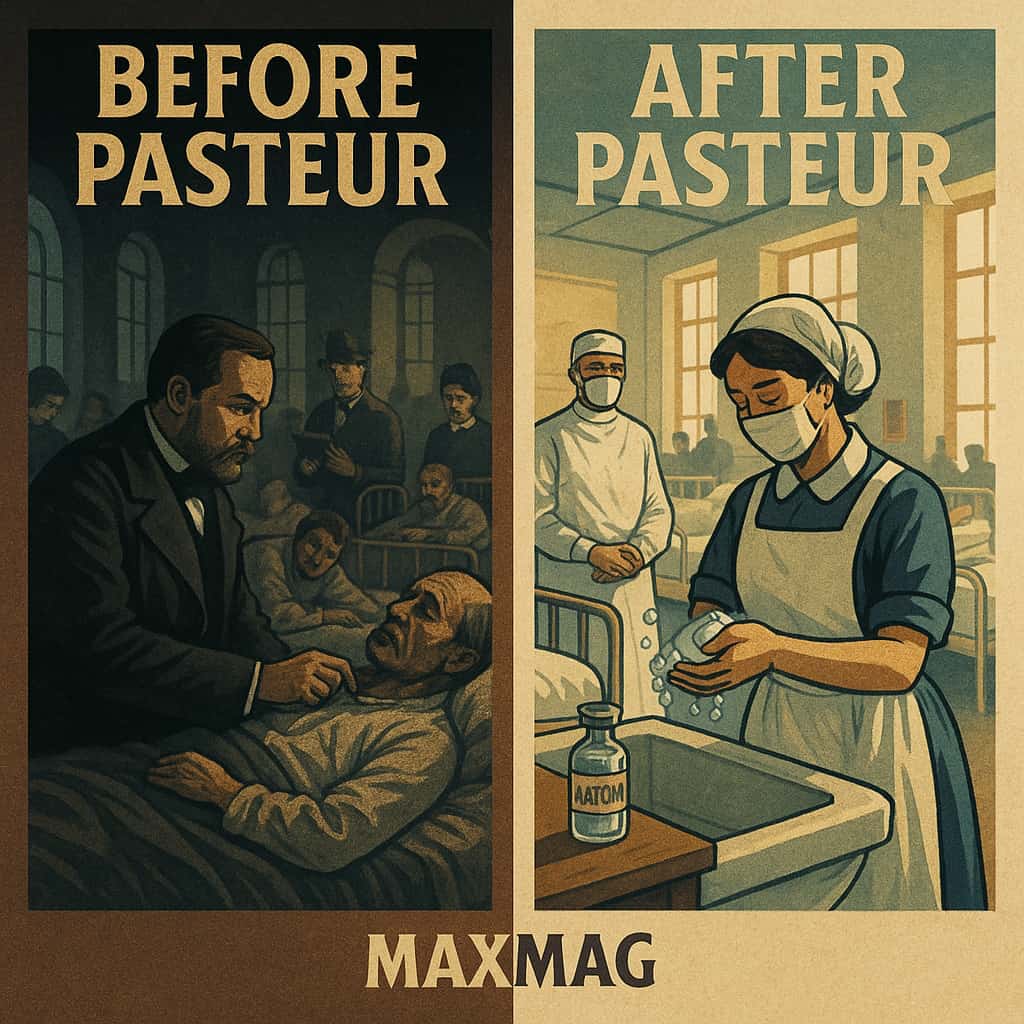

From germ theory to modern public health

Pasteur’s most enduring legacy lies in the shift from vague notions of miasma—bad air—to a concrete, testable model of disease caused by specific microbes. This germ theory of disease, developed in parallel and sometimes in rivalry with figures like Robert Koch, opened the door to everything from antiseptic surgery to water treatment and mass vaccination campaigns.

The Louis Pasteur biography thus sits at the crossroads of microbiology and public policy. Once you accept that tiny organisms cause infections, entire strategies for preventing epidemics become possible: cleaning hospitals, treating water supplies, regulating food production and designing vaccines.

Everyday echoes of a 19th-century science revolution

For most people, the impact of this 19th-century science is felt not in lecture halls but in everyday routines. We drink pasteurised milk, trust that vaccines have been tested, and assume that hospitals are designed to prevent infections rather than spread them. These assumptions are the quiet outcome of the work described in the Louis Pasteur biography.

Even global observances like World Rabies Day—held each year on the anniversary of his death and aimed at eliminating rabies through vaccination and education—directly trace their symbolism to his breakthrough rabies work.

In this sense, the figure of Louis Pasteur is woven into the fabric of modern life, from veterinary care to food safety regulations.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Family tragedies and a guarded private world

Behind the public honours and scientific triumphs, the Louis Pasteur biography includes moments of deep personal grief. He and his wife, Marie, lost several of their children to infectious diseases—tragedies that almost certainly strengthened his determination to combat the microbes that seemed to strike families at random.

Friends and colleagues described him as serious, sometimes severe, but also capable of warmth and loyalty. His marriage provided a stable base from which he could pursue risky and exhausting research programmes. The home became both a refuge and, at times, an extension of the laboratory, with experiments encroaching on domestic space.

Faith, patriotism and 19th-century science

Pasteur’s religious views have been widely discussed, and occasionally mythologised. Some have cast him as a defender of traditional faith against scientific scepticism, while others highlight his pragmatic emphasis on experimental evidence. The reality is more nuanced: he lived in a France wrestling with questions of secularism, national identity and the role of science in public life.

What is clear from the Louis Pasteur biography is his deep patriotism. He saw his work as part of a broader national project to restore French prestige after military defeat and political upheaval. Victories over disease and industrial crises were, for him, also victories for France.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Louis Pasteur

The rabies vaccine and a risky decision

The last decade of Pasteur’s life was overshadowed by illness—he suffered strokes that left him partially paralysed—but also marked by growing international fame. The rabies vaccine made him a household name, and patients travelled from across Europe and beyond to seek treatment.

The decision to treat Joseph Meister, described earlier, remained the defining moment of this period. It showed a scientist willing to move from animal trials to human intervention in a desperate situation, balancing incomplete data against almost certain death. For many, this episode in the Louis Pasteur biography represents the ethical tightrope walked by pioneers in experimental medicine.

The founding of the Pasteur Institute

As he aged, Pasteur turned increasingly to institution-building. In 1888, the Pasteur Institute was founded in Paris as a centre for research, treatment and teaching focused on infectious diseases. It became a model for similar institutes worldwide and remains an important research organization today.

The Institute anchored his legacy in bricks, mortar and ongoing scientific work. The Louis Pasteur biography does not end with his death in 1895; it continues in the generations of scientists trained in his methods and inspired by his example.

The Lasting Legacy of the Louis Pasteur biography

Vaccines, public health and the modern world

In the 21st century, debates about vaccination, antibiotic resistance and pandemic preparedness all echo themes first raised in the Louis Pasteur biography. His insights into microbes underpin not only classic vaccines but also new approaches in biotechnology, from engineered microbes that produce medicines to rapid diagnostic tests.

At the same time, the controversies around his methods remind us that science is a human enterprise, shaped by ambition, error and revision as well as by insight. For historians of medicine and public health, his life offers a rich case study in how evidence is gathered, presented and contested.

How the Louis Pasteur biography shapes today’s debates

When public trust in science falters, it is often because people feel shut out of the process or suspicious of its motives. The Louis Pasteur biography offers a counterpoint: here is a scientist who spoke directly to farmers, industrialists and politicians; who staged public experiments; and who, for all his flaws, understood that scientific authority is strengthened, not weakened, by open demonstration.

Understanding the Louis Pasteur biography helps us see why germ theory, vaccines and public health policies are not abstract doctrines imposed from above, but hard-won responses to real suffering. In that sense, his story remains a living part of how societies think about disease, evidence and collective responsibility.

Frequently Asked Questions about Louis Pasteur biography

Q1: What is the central focus of the Louis Pasteur biography?

Q2: Why is Louis Pasteur considered a key figure in germ theory history?

Q3: How did the rabies vaccine influence the Louis Pasteur biography?

Q4: What controversies surround the Louis Pasteur biography?

Q5: How does the Louis Pasteur biography relate to vaccine development today?

Q6: Why should non-scientists read about the Louis Pasteur biography?