On a chilly morning in rural Kent, an ageing gentleman in a crumpled hat walked slow circles along a gravel path he called his “Sandwalk”. From a distance he looked like any other Victorian country squire out for exercise. Yet the story behind that walk, and behind this Charles Darwin biography, is the story of a man whose ideas quietly blew a hole in the way humans understood themselves and the living world. His evolutionary theory did not arrive in a blaze of lightning. It grew instead from seasickness, notebooks, letters, fossils and doubts – from a lifetime spent trying to make sense of nature’s bewildering variety.

A compelling Charles Darwin biography has to do more than list dates and books. It has to capture the tension at the heart of his life: a cautious, polite English naturalist, schooled in theology, who ended up arguing that humans were not set apart from animals but part of the same branching tree of life. He never saw himself as a revolutionary, yet his evolutionary theory of natural selection turned biology into a historical science and forced society to rethink what it means to be human.

Charles Darwin biography at a glance

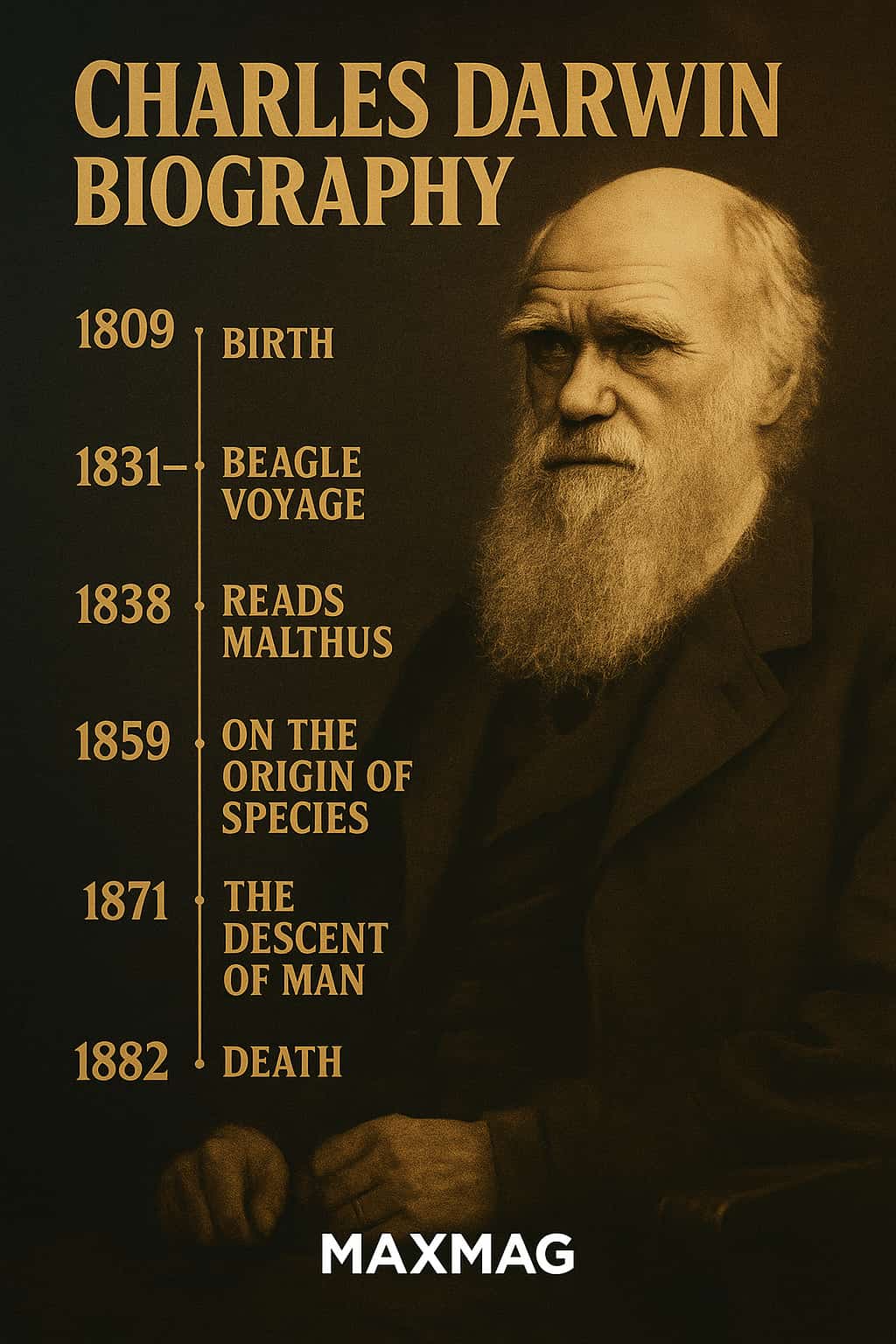

- Who: Charles Darwin, English naturalist and evolutionary biology pioneer, born 1809 in Shrewsbury.

- Field and era: Natural history and the emerging history of biology in 19th-century science.

- Headline contributions: Developed the natural selection theory to explain how species evolve; showed that humans share ancestry with other animals.

- Why he matters today: Modern genetics, medicine, ecology and conservation still rely on the framework introduced in this Charles Darwin biography’s central ideas.

Key takeaway: Darwin began as a conventional gentleman of Victorian science, but his evolutionary theory reshaped biology and continues to influence how we think about life and ourselves.

Early Life and Education of Charles Darwin

How the Charles Darwin biography begins: a comfortable but questioning childhood

Charles Darwin entered the world on 12 February 1809, into a prosperous family that straddled money and ideas. His father, Robert Darwin, was a successful physician; his grandfathers included the industrialist Josiah Wedgwood and Erasmus Darwin, a doctor and poet who had toyed with early evolutionary speculation. The young Charles grew up in a large house on the edge of Shrewsbury, surrounded by gardens and fields, in an England being transformed by factories, canals and the early railways of Victorian science.

At school he was no prodigy. He did not shine in Latin and Greek, the classic markers of success. Instead, he collected beetles, admired the countryside, and conducted small, messy experiments. Friends later recalled a boy who preferred shooting and outdoor rambles to the schoolroom, already drawn to the raw material that would feed the evolutionary theory he would one day frame. The seeds of this Charles Darwin biography were being quietly sown in hedgerows and riverbanks rather than in formal lectures.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s early life was comfortable but unconventional, shaped less by schoolbooks than by a family steeped in curiosity and by long hours spent observing nature.

From failed doctor to would-be clergyman

At sixteen, Darwin was sent to Edinburgh University to follow his father into medicine. It did not go well. He loathed the blood and agony of surgery in an era before anaesthetics and skipped lectures whenever he could. Instead, he gravitated toward the natural history societies of the city, learning taxidermy from a freed Black man from Guyana and joining student groups that debated geology and marine life. This part of the Charles Darwin biography shows a young man already edging away from the family script.

After two unhappy years, his father abandoned the medical plan and proposed a new path: the Church. A country clergyman could live respectably and indulge a taste for collecting beetles and plants. Darwin moved to Cambridge to study for holy orders, but once again found himself drawn towards natural history. Under the influence of botanist John Stevens Henslow and geologist Adam Sedgwick, he learnt careful observation, rigorous note-taking and the emerging history of biology that emphasised deep time.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s failure as a medical student and his lukewarm commitment to theology pushed him toward the one thing that consistently excited him: studying the natural world.

Charles Darwin biography and the Birth of His Big Ideas

The Beagle voyage: adventure, seasickness and specimens

The turning point in any serious Charles Darwin biography comes with a letter from Henslow. In 1831, he suggested Darwin as a gentleman companion and unofficial naturalist on a surveying voyage of HMS Beagle. At first Robert Darwin said no: the trip seemed risky, unpaid and unnecessary. Only after lobbying by relatives did he relent. It was one of the most consequential changes of mind in the history of biology.

The Beagle circumnavigated the globe over almost five years. Darwin was miserably seasick at sea, but tireless ashore. In South America he climbed volcanoes, rode across the Pampas with gauchos, collected fossils of gigantic extinct mammals and noted strange patterns in the distribution of living species. On the Galápagos Islands he saw mockingbirds and finches that differed subtly from island to island, a detail that would later become iconic in this Charles Darwin biography and in the story of evolutionary biology.

Key takeaway: The Beagle voyage supplied Darwin with an extraordinary stock of observations and specimens, showing him a world in flux and hinting that species might not be fixed.

Notebooks, Malthus and the natural selection theory

Back in England, Darwin settled into the bustling world of London’s Victorian science, surrounded by leading geologists and naturalists. As he catalogued his specimens and wrote up the voyage, his private notebooks began to fill with more dangerous thoughts. He sketched branching diagrams of life, speculating about common ancestors and gradual change. These sketches are among the most revealing artefacts in any Charles Darwin biography.

The decisive intellectual jolt came in 1838, when he read the economist Thomas Malthus on population. Malthus argued that populations grow faster than food supplies, so there is always competition and struggle. Darwin recognised that if more individuals are born than can survive, and if some inherit traits that help them cope better, then those traits will become more common over generations. This was the core of his evolutionary theory: the natural selection theory that could explain how adaptation and diversity arise without needing each species to be separately designed.

Key takeaway: By combining his global observations with Malthus’s cold arithmetic of population, Darwin found a mechanism—natural selection—that could power evolution.

Key Works and Major Contributions of Charles Darwin

On the Origin of Species: a slow-brewed revolution

No Charles Darwin biography can avoid centring on the 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species. Yet the book was not a sudden manifesto. For more than twenty years, Darwin tested his evolutionary theory in private, fearing the uproar it might cause. He studied barnacles for eight years, becoming the world expert on a tiny group of crustaceans, partly to strengthen his understanding of variation and species boundaries.

In Origin, he built his case like a barrister. He began with artificial selection, which Victorian readers knew well: pigeon fanciers, dog breeders and farmers had long been shaping animals and crops. Then he argued that nature itself acted as a selector, favouring traits that fit particular environments. Over vast stretches of time, this natural selection theory could explain new species, complex organs and the pattern of life’s history. It was a sweeping piece of evolutionary theory, yet it read like a calm, evidence-based argument rather than a manifesto.

Key takeaway: On the Origin of Species provided not just the claim that species evolve, but a detailed argument for how evolution happens through natural selection.

Human evolution debate: The Descent of Man and beyond

For a while, Darwin avoided directly tackling human origins. The implications of the Charles Darwin biography’s central idea were obvious: if all life shares common ancestry, humans are part of that branching tree. In 1871, he confronted this directly with The Descent of Man, arguing that humans and other animals share a common ancestor and that our mental and moral capacities evolved gradually.

He followed this with The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, comparing facial expressions and behaviours across species. These works extended evolutionary biology into psychology and ethics, fuelling the human evolution debate that still runs hot today. They also cemented Darwin’s role not just as a naturalist cataloguing species, but as a thinker probing what makes humans both distinctive and continuous with the rest of life.

Key takeaway: By applying evolutionary thinking to humans, Darwin transformed discussions about mind, morality and our place in nature.

Coral reefs, orchids and earthworms: the breadth of a Victorian naturalist

Darwin’s contributions were broader than many readers of a Charles Darwin biography expect. His early work on coral reefs explained how atolls form, uniting geology and biology. In his book on orchids, he showed how intricate flower structures made sense as adaptations to specific pollinators, a vivid example of his evolutionary theory in action.

His last major work, on earthworms and soil, might look modest beside Origin. Yet in it he patiently demonstrated how humble worms, through endless small actions, can reshape entire landscapes. The book reads almost like an allegory for his view of evolution: vast change built from tiny, repeated processes over time.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s scientific range—from reefs to worms—illustrated how natural selection could illuminate phenomena across the natural world, reinforcing his status as an evolutionary biology pioneer.

Methods, Collaborations and Working Style

Down House: a country home turned laboratory

After marrying his cousin Emma Wedgwood, Darwin settled at Down House in Kent, turning it into a quiet hub of Victorian science. The Charles Darwin biography is, in many ways, the story of this house: children racing through corridors while their father observed climbing plants in pots, or sprinkled pollen onto petals in the greenhouse.

His methods were deceptively simple. He designed small experiments with clear questions: could seeds survive in seawater and still germinate, helping explain how plants reached islands? How did insect-eating plants lure and digest their prey? He recorded results meticulously, filling notebooks and lab books with figures, sketches and comments. Down House became both a family home and a long-term research station for the history of biology.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s working style relied on modest, repeatable experiments and obsessive note-taking, turning ordinary domestic spaces into a laboratory for evolutionary theory.

Letters as a global research network

Darwin’s correspondence formed another crucial tool. He wrote thousands of letters to botanists, farmers, pigeon breeders, colonial officials and other naturalists scattered across the British Empire and beyond. They sent him seeds, observations and specimens; he responded with questions, thanks and his own interpretations. This web of contacts, central to any detailed Charles Darwin biography, prefigures modern scientific networks.

Through these letters, he could compare how similar species behaved in different climates, how breeders in various regions understood inheritance, and how geological formations matched across continents. Collaboration was not a buzzword in 19th-century science, but Darwin’s reliance on others’ eyes and hands made his work deeply collaborative in practice.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s network of correspondents extended his reach worldwide, letting him test and refine his ideas against a steady flow of real-world information.

Working through illness and doubt

The Charles Darwin biography is also a story of chronic illness. For much of his adult life, Darwin suffered from bouts of nausea, palpitations, skin problems and exhaustion. Modern doctors have proposed everything from Chagas disease to anxiety disorders; the exact cause remains uncertain. What is clear is that he had to structure his days carefully, working in concentrated bursts and then resting.

Illness and doubt sometimes slowed him, but they also contributed to his cautious, self-critical approach. He rarely rushed into print and constantly tested his evolutionary theory against new data. This restraint gives his work its distinctive tone: assertive when the evidence is strong, tentative when it is not.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s frailty did not stop his work; it shaped a careful, reflective style that strengthened the credibility of his arguments.

Controversies, Criticism and Misconceptions

Religious reactions and the shock of evolution

When On the Origin of Species appeared, it sold out quickly and triggered immediate controversy. Some clergy and laypeople saw Darwin’s evolutionary theory as a direct attack on religious belief. Others tried to reconcile it with faith, seeing natural selection as a tool in the hands of a creator. The clash between Victorian science and traditional theology became a central thread in the Charles Darwin biography and in the wider story of 19th-century science.

The famous exchange between Bishop Samuel Wilberforce and Darwin’s supporter Thomas Henry Huxley at Oxford in 1860 has become a symbol of this conflict, even if later retellings are somewhat dramatized. Whether or not the sharpest lines were really spoken as reported, the episode shows how Darwin’s ideas forced public debates about the authority of scripture versus the authority of evidence.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s work did not make religion disappear, but it dramatically changed the terms of conversation between science and faith.

Social Darwinism and the misuse of evolutionary theory

One of the most persistent misconceptions around this Charles Darwin biography is the notion that Darwin himself coined or endorsed “social Darwinism” – the idea that “survival of the fittest” justifies extreme competition and social inequality. In fact, the phrase came from philosopher Herbert Spencer, and many harsh political doctrines that claimed Darwin as inspiration cherry-picked his language while ignoring his nuanced views.

Darwin recognised struggle in nature, but he also wrote about cooperation, sympathy and the evolution of moral instincts. His work on human evolution explicitly treated moral behaviour as something natural selection could favour when living in groups. Later thinkers who used evolutionary theory to defend racism or ruthless capitalism were, in many ways, twisting his legacy rather than faithfully extending it.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s ideas have been used to support crude social ideologies he did not endorse, reminding us to distinguish his evolutionary theory from later political distortions.

Myths that still shape the Charles Darwin biography

Over time, legends have grown around Darwin. One common myth is that he realised the full significance of the Galápagos finches while still on the islands. In reality, he did not label his bird specimens by island, and only later—after comparing them with collections in London—did the pattern click. Another myth is a dramatic deathbed conversion in which he supposedly renounced evolution. Historians have found no reliable evidence for this story.

These myths persist partly because they offer a simple narrative: the sudden eureka moment, the last-minute religious reconciliation. The real Charles Darwin biography is more prosaic and more interesting: decades of careful work, slow shifts in belief, and a mind that rarely claimed more certainty than the evidence allowed.

Key takeaway: Separating myth from history reveals a more complex, human Darwin, whose intellectual journey was gradual rather than dramatic.

Impact on Biology and on Wider Society

Evolution as the backbone of modern science

Before Darwin, much of natural history was about classification: naming species, arranging them in neat hierarchies, and assuming they were fixed. After Origin, biology became a historical science, focused on change over time. Evolutionary theory turned a static catalogue into a dynamic story, in which every species had a past and a possible future.

Today, fields from genetics to ecology rely on this framework. When bacteria evolve resistance to antibiotics, when viruses adapt to new hosts, when conservationists worry about whether species can adapt to rapid climate change, they are all thinking in Darwinian terms. Modern laboratories may look nothing like Down House, but the logic that underpins much of their work is threaded back through this Charles Darwin biography.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s ideas gave biology a unifying narrative and a powerful set of questions about adaptation, ancestry and change.

Changing how humans see themselves

Darwin’s impact on wider society has been just as profound. By placing humans firmly within the animal kingdom, his evolutionary theory challenged assumptions about human exceptionalism. We were no longer a separate creation, but a recently evolved twig on a vast and ancient tree of life.

This shift filtered into philosophy, literature and politics. Debates about human nature, free will and morality increasingly engaged with the idea that our minds and cultures have evolutionary roots. In some quarters, this fuelled pessimism; in others, it encouraged a sense of kinship with other species and a more grounded understanding of our limits.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s work continues to shape moral and cultural debates by forcing us to consider ourselves as part of nature rather than above it.

Personal Beliefs, Character and Private Life

Family life at Down: a scientist among children

A full Charles Darwin biography must make room for the domestic scenes at Down House. Darwin was not a remote, austere figure locked away from his family. He adored his ten children, seven of whom survived to adulthood, and they roamed freely through his study and gardens. He sometimes turned their games into small experiments, asking them to help time plant movements or observe insects.

Visitors noted the informality of the household. Meals were lively, jokes were common, and children clambered on their father’s knee even as he discussed Victorian science with visitors. This warmth complicates the stereotype of the cold scientific mind; the evolutionary biology pioneer emerges as a devoted father whose work was woven into everyday family life.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s home was both a family sanctuary and a workspace, showing how deeply his science was embedded in ordinary life.

Illness, grief and inner conflict

Darwin’s chronic illness was not the only shadow over his life. In 1851, his beloved daughter Annie died at the age of ten after a long illness. The loss devastated him. For many readers of a Charles Darwin biography, this moment is one of the most affecting: a father watching helplessly as medicine and prayer fail to save his child.

Annie’s death deepened Darwin’s doubts about traditional religious explanations for suffering. It did not turn him into a crusading atheist, but it added weight to his growing sense that the natural world, with its beauty and its pain, was governed by impersonal laws rather than constant direct intervention. His personal grief and his evolutionary theory developed in painful parallel.

Key takeaway: Personal tragedy and chronic illness shaped Darwin’s emotional world, reinforcing his turn towards a more naturalistic understanding of life.

Faith, doubt and a changing outlook

When he went up to Cambridge, Darwin was a conventional young Anglican who accepted the basic teachings of the Church. By the time his evolutionary theory had matured, his beliefs had shifted. He became, in his own words, more of an agnostic, doubting human capacity to know ultimate truths about God.

Emma remained more religious, and their letters reveal a marriage that made room for disagreement. She worried that his loss of faith might separate them in eternity; he worried about causing her pain. The Charles Darwin biography is therefore also a portrait of a couple negotiating the pressure that new scientific ideas can place on older beliefs.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s religious views evolved gradually, shaped by science, suffering and love, leaving him respectful of faith but unable to share Emma’s convictions.

Later Years and Final Chapter of Charles Darwin

Relentless work in the twilight years

In his later decades, Darwin could have retired into comfortable fame, letting others fight over his evolutionary theory. Instead, he kept working. Books on insectivorous plants, climbing plants and earthworms poured from his study. He remained engaged with the growing field of evolutionary biology, corresponding with younger researchers and responding, patiently or sharply, to critics.

Even as his body weakened, his curiosity stayed acute. He continued to test ideas, revise his views in light of new evidence and worry over the details of his arguments. For readers of a Charles Darwin biography, this persistence can be both inspiring and exhausting to contemplate.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s final years were marked by sustained creativity, not retirement, as he extended and applied his ideas across the natural world.

Death, Westminster Abbey and a national symbol

Darwin died at Down House on 19 April 1882, aged 73. At first, his family assumed he would be buried quietly in the local churchyard. But friends and supporters moved quickly, arguing that his contributions to Victorian science and the history of biology justified a more public honour.

Within days, arrangements were made for his burial in Westminster Abbey, near Isaac Newton. The ceremony marked a remarkable transformation captured in any thoughtful Charles Darwin biography: a once-controversial thinker, whose ideas had alarmed many religious leaders, now laid to rest at the symbolic heart of Britain’s religious and national life.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s interment in Westminster Abbey signalled his elevation from contentious naturalist to national figure, even as debates over his ideas continued.

The Lasting Legacy of the Charles Darwin biography

Why Darwin still matters in the 21st century

Today, the significance of this Charles Darwin biography is measured not only in history books but in laboratories, hospitals and conservation projects. Evolutionary theory underpins our understanding of emerging diseases, antibiotic resistance, crop breeding and ecosystem resilience. Without Darwin’s insights, the modern life sciences would be missing their central organising principle.

At the same time, Darwin’s story offers a template for how big scientific changes happen. Revolutionary ideas do not always spring fully formed from dramatic geniuses. Sometimes they emerge from decades of slow, cumulative work by a cautious mind willing to follow evidence—even when it leads away from comforting beliefs.

Key takeaway: Darwin’s legacy lives both in the practical tools of modern biology and in a deeper understanding of how scientific revolutions unfold.

What the Charles Darwin biography reveals about science and society

There is another reason the Charles Darwin biography continues to fascinate. It shows how tightly science and society are intertwined. Darwin’s natural selection theory challenged religious ideas, social hierarchies and views of human nature, and it was in turn shaped by the imperial networks, economic theories and cultural anxieties of 19th-century science.

Understanding Darwin helps us see similar patterns today, when new fields—from genetics to artificial intelligence—raise fresh moral and political questions. His life reminds us that scientific knowledge is powerful precisely because it changes how we live, govern, heal and argue. That power brings responsibility: to use evolutionary theory and other scientific tools with humility, care and an awareness of past misuses.

In the end, what makes this Charles Darwin biography resonate is not just the story of a shy English naturalist, but the way his ideas continue to shape our sense of who we are and how we fit into the living world.

Q1: Who was Charles Darwin and why is his life often explored through a detailed Charles Darwin biography?

Q2: What is the core idea of Darwin’s evolutionary theory?

Q3: How did the Beagle voyage influence the Charles Darwin biography?

Q4: Did Darwin’s ideas immediately transform Victorian science?

Q5: What are some common myths about Charles Darwin and his work?

Q6: Why does the Charles Darwin biography still matter today?