In the deep mythological past of Greece, before the familiar gods of Olympus rose to prominence, an older, more elemental pantheon ruled the cosmos. These deities, known as the Greek mythology Titans, were colossal figures tied not to the moral themes of humanity but to raw, natural forces like time, memory, and light. Their myths stretch across creation, rebellion, downfall, and even cultural rebirth.

Understanding the Greek mythology Titans isn’t just a matter of learning ancient tales—it’s an essential key to grasping how the Greeks imagined the universe and humanity’s place within it. Their influence echoes across literature, philosophy, art, and even modern language, remaining relevant in subtle yet profound ways.

From Chaos to Order: The Origins of the Titans

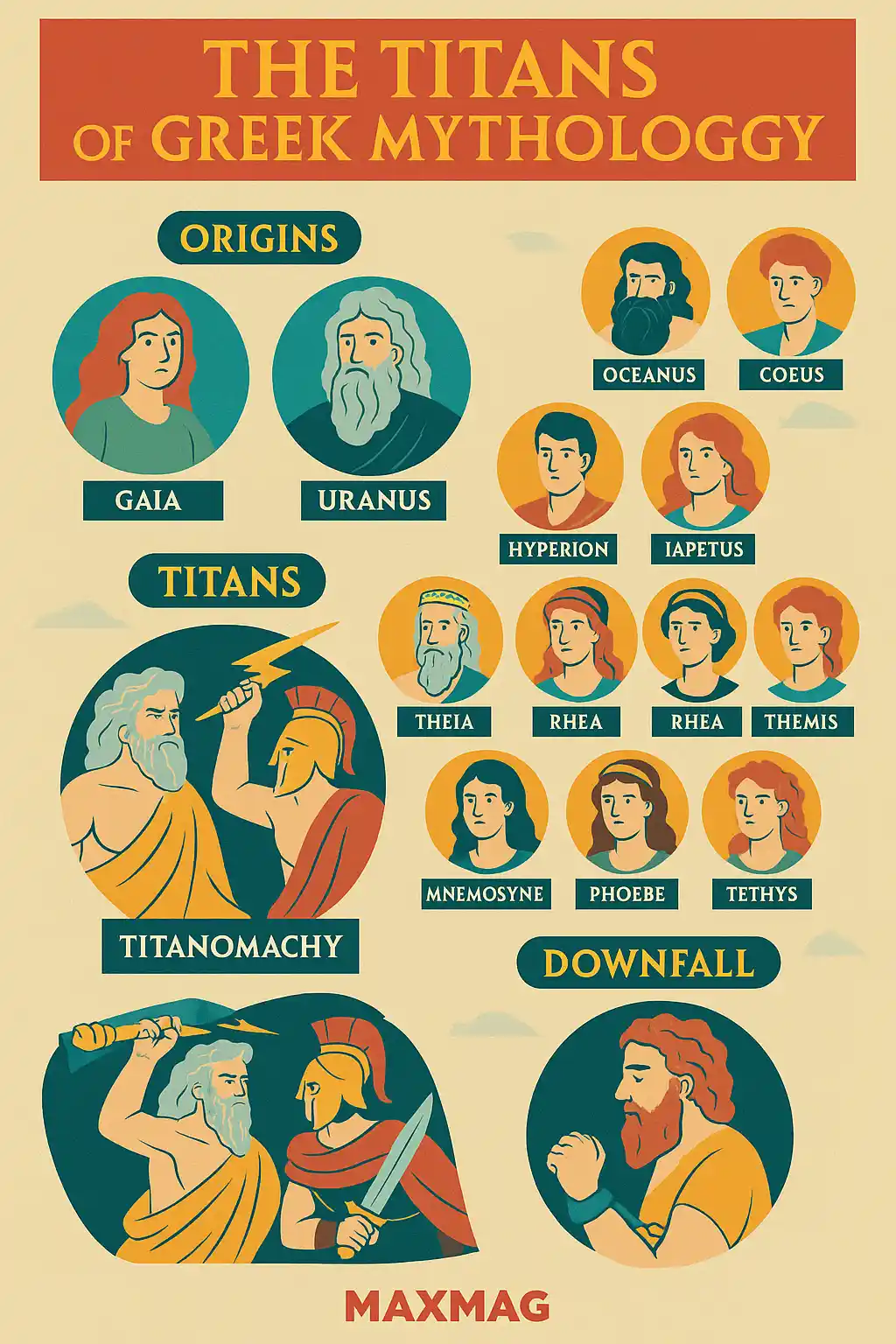

The story of the Titans begins in Chaos, the primordial void. From Chaos came Gaia (Earth), Tartarus (the abyss), Nyx (Night), Erebus (Darkness), and Eros (Love). Gaia, acting alone or with Uranus (Sky), gave birth to several offspring—most notably the Greek mythology Titans.

This first generation of Titans consisted of twelve beings:

-

Oceanus: Embodiment of the great, encircling river thought to surround the world

-

Coeus: Linked to intelligence and the celestial axis

-

Crius: Associated with constellations

-

Hyperion: Representing heavenly light

-

Iapetus: Often tied to mortality and craftsmanship

-

Cronus: The youngest and most ambitious, embodying destructive time

-

Theia, Rhea, Themis, Mnemosyne, Phoebe, and Tethys: Goddesses tied to divine law, memory, sight, moonlight, and the seas

The Titans were the children of Earth and Sky—quite literally the building blocks of the world. But their rise to power came only through violence and upheaval.

For a closer look at early Greek cosmology and divine genealogy, visit the Perseus Digital Library at Tufts University, a respected hub of classical texts and commentaries.

The Cosmic Overthrow of Uranus

As Uranus grew increasingly tyrannical, he feared the monstrous children Gaia had borne—especially the Hecatoncheires (hundred-handed giants) and Cyclopes. In his terror, he locked them away deep in the Earth, causing Gaia immense pain. She turned to her Titan children for aid. Only Cronus stepped forward.

Wielding a sickle made from adamantine, Cronus ambushed Uranus and severed him, ending his reign and allowing the Titans to take power. This act symbolized not only a generational rebellion but the beginning of cyclical time—a concept crucial to both myth and early science.

From Uranus’ blood sprang new beings: the Furies (avengers), Giants, and the Meliae (ash-tree nymphs). The Greek mythology Titans now ruled during what the Greeks considered a Golden Age—a time of harmony, no labor, and no warfare.

Cronus’ Reign and the Birth of Rebellion

Though his rule was considered golden, Cronus himself became a tyrant, repeating his father’s mistake. He feared prophecy—that one of his own children would overthrow him. To prevent this fate, he swallowed each child born to his sister-wife Rhea: Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades, and Poseidon.

But Rhea, desperate to save her sixth child, devised a plan. She gave Cronus a swaddled stone instead of baby Zeus and spirited the infant away to be raised in secret on the island of Crete. There, Zeus grew under the care of nymphs and goats, nourished by divine honey and protected by mythical warriors.

When Zeus matured, he returned to confront his father. With the help of Metis (wisdom), he tricked Cronus into vomiting up his swallowed siblings. Together, the six Olympians prepared for war.

For mythological insights into Rhea’s rebellion and Zeus’s growth, Theoi Greek Mythology offers excellent classical references and primary source excerpts.

Titanomachy: The Great War Between Titans and Olympians

This epic war, known as the Titanomachy, lasted ten years and shook the very foundations of Greek myth. On one side stood the old order—the Greek mythology Titans—led by Cronus and supported by many of his brothers. On the other were Zeus and his liberated siblings.

Realizing their power was not enough, Zeus descended into Tartarus, freed the Hecatoncheires and Cyclopes, and earned their allegiance. As a reward:

-

Zeus received the thunderbolt

-

Poseidon the trident

-

Hades the helm of invisibility

The war culminated in the defeat of the Titans. Zeus hurled them into Tartarus and set the Hecatoncheires as their guards. Only a few Titans—like Prometheus and Oceanus—escaped this fate by either neutrality or alliance with the Olympians.

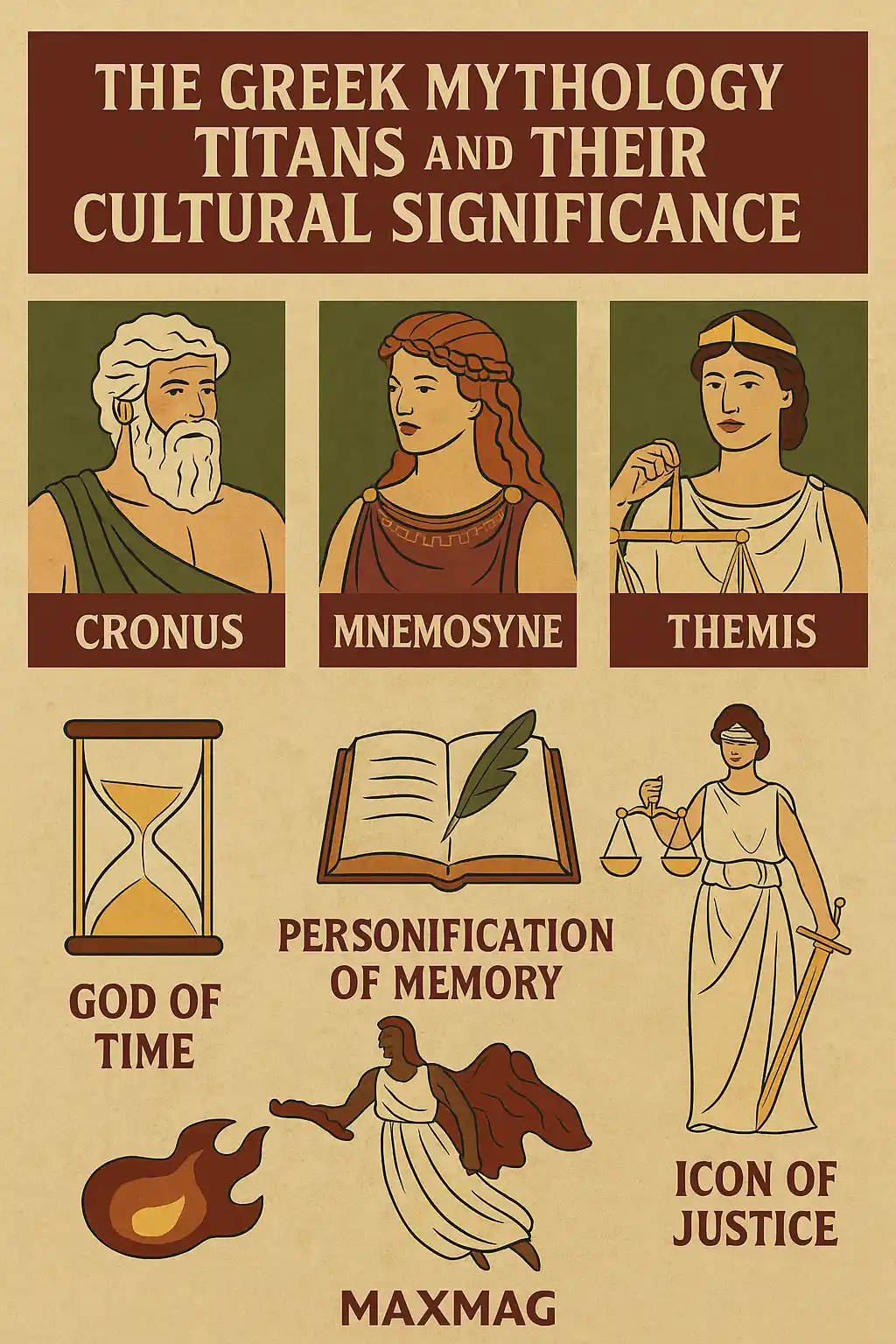

The Greek Mythology Titans and Their Cultural Significance

The Greek mythology Titans aren’t just ancient deities relegated to forgotten myths—they embody primal forces that still shape cultural archetypes and collective imagination.

Cronus and the Nature of Time

Cronus (often conflated with “Chronos”) represents time’s destructive cycle. In many Renaissance works, he’s shown devouring his children—a literal image of time consuming all things. Modern concepts like “Father Time” descend from this myth, blending the Titan’s image with linear chronology.

Mnemosyne and the Role of Memory

As the mother of the Muses (with Zeus), Mnemosyne personifies memory as the mother of creativity. She is invoked in literature, poetry, and ritual. In philosophy, she is tied to the idea that knowledge is rooted in remembrance, as seen in Plato’s theory of recollection.

Themis and Justice

Lady Justice—depicted blindfolded, holding scales—finds her roots in Themis, the Titaness of divine law and order. Her principles guided both gods and mortals before codified human laws ever existed.

For an academic perspective on Titans and their psychological meaning, The National Endowment for the Humanities explores classical themes through modern philosophical lenses.

Titans in Later Greek Myth and Human Evolution

Although the Titans were overthrown, their presence lingers in myths that follow:

-

Prometheus, son of Iapetus, steals fire from Olympus to give to humanity. For this, Zeus chains him to a rock where an eagle devours his liver daily. His story represents defiance, sacrifice, and human advancement.

-

Atlas, another son of Iapetus, is condemned to hold up the sky—forever bearing the burden of rebellion.

-

Epimetheus, Prometheus’s brother, marries Pandora—the first woman—and opens the jar that releases suffering into the world.

These tales link the Greek mythology Titans directly to human fate and consciousness. Their stories are not merely divine—they are intimately human.

Titans in Modern Times: Literature, Games, and Psychology

The Titans remain deeply embedded in Western art and imagination:

-

In John Milton’s “Paradise Lost”, the fallen angels echo the grandeur and tragedy of the Titans.

-

In Nietzsche’s philosophy, the tension between the Apollonian (order) and Dionysian (chaos) can be traced back to mythic structures born from the Titans’ fall.

-

Carl Jung saw figures like Prometheus as psychological archetypes—symbolizing rebellion, enlightenment, and the journey toward individuation.

Even today, Greek mythology Titans appear in:

-

Blockbusters (Wrath of the Titans, Clash of the Titans)

-

Books (Rick Riordan’s Heroes of Olympus)

-

Video games (Hades, God of War)

-

Science and technology (Titan rockets, Saturn missions)

The J. Paul Getty Museum has an entire archive on mythological motifs in Western art—perfect for exploring how the Titans live on in painting, sculpture, and beyond.

Metaphors and Language: Titans All Around Us

You’ve likely used Titan-related language today without realizing it:

-

“Titanic” effort = monumental power

-

“Atlas” = maps or burden

-

“Promethean” = bold, inventive, daring

Even in astrology, Saturn (Cronus) governs structure, discipline, and karma. In the business world, companies like Titan Machinery or Saturn Corporation channel mythological energy into branding.

These metaphors prove that while their temples may lie in ruins, the Greek mythology Titans remain giants in our linguistic landscape.

Forgotten Yet Powerful: Minor Titans and Their Impact

Not all Titans had starring roles, but many held symbolic significance:

-

Phoebe: Associated with the Oracle of Delphi

-

Tethys: Gave birth to the rivers and ocean nymphs

-

Theia: Mother of Helios (Sun), Selene (Moon), and Eos (Dawn)

These characters appear less in literature but often feature in astronomy, where their names grace moons, asteroids, and other celestial objects.

Conclusion: Why the Greek Mythology Titans Still Matter

The Greek mythology Titans were creators, destroyers, rebels, and visionaries. Their narratives remind us that change is inevitable, power is cyclical, and wisdom is born from memory and myth. Their stories offer more than entertainment—they provide frameworks for understanding time, law, creativity, and our inner struggles.

They represent the ancient world’s deepest truths and fears. And like all great myths, they transcend time, echoing into the modern world through words, art, and symbolic thought. When we speak of Titans, we speak of everything vast, eternal, and profoundly human.

FAQ About the Greek Mythology Titans

Q1: Who were the Greek mythology Titans?