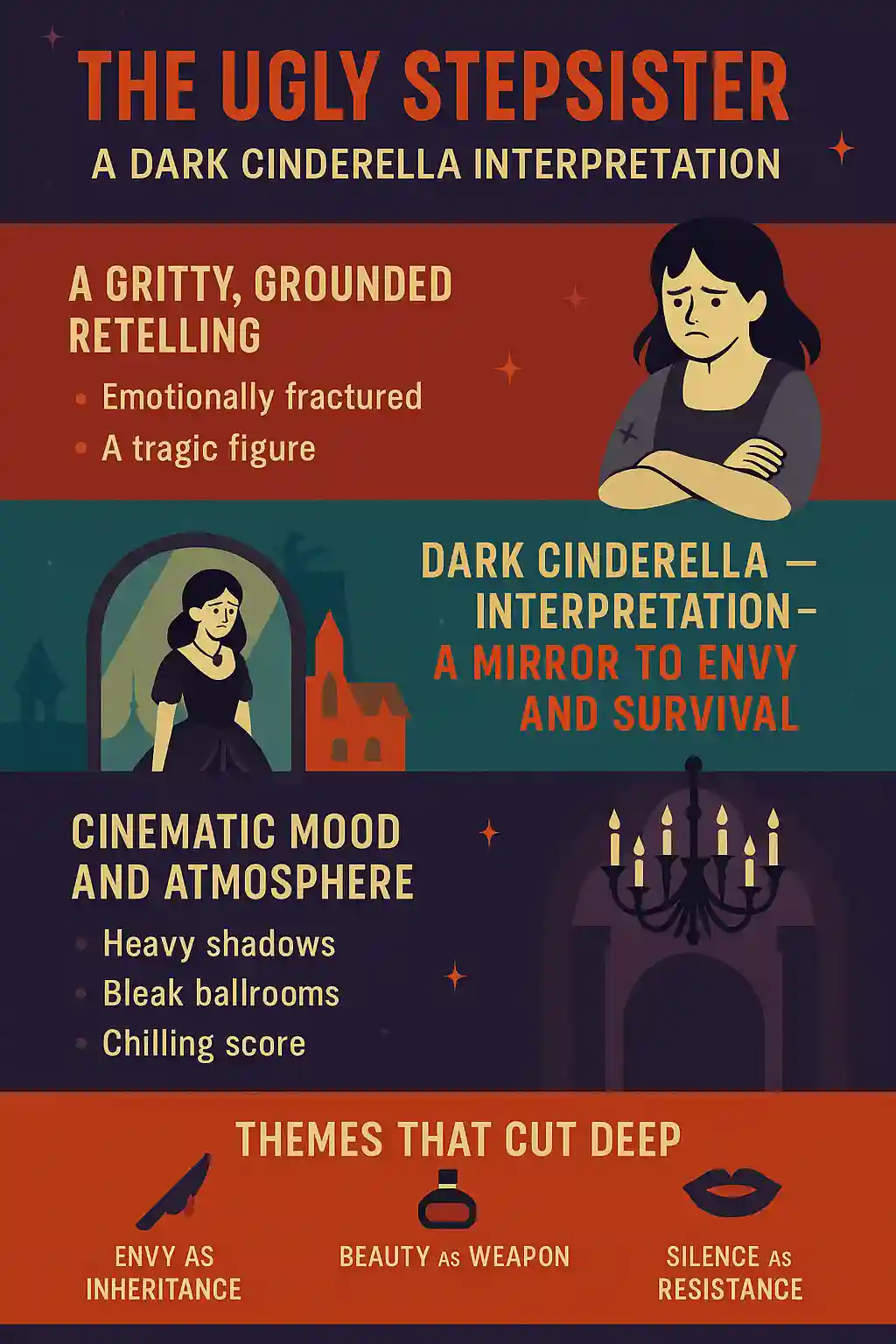

Cinderella’s story has long been associated with magical transformations, glass slippers, and dreamy ballroom scenes. But The Ugly Stepsister offers something entirely different—a raw, unsettling, and deeply emotional journey through the lens of a dark Cinderella interpretation. Here, the tale isn’t about wish fulfillment, but about pain, envy, and survival in a world where appearances hide deeper scars.

Right from the first scene, it’s clear this isn’t the Cinderella we know. There’s no whimsical fairy godmother, no charming prince waiting to rescue. Instead, we meet a protagonist hardened by years of rejection, whose transformation comes not from magic, but from trauma. In this version, “happily ever after” is a question mark—if it exists at all.

Get the best of tech, movies, and culture from MaxMag — weekly.

SubscribeA Gritty, Grounded Retelling

This reinterpretation dives deep into the psyche of Cinderella, reimagining her not as a passive damsel but as a complex, emotionally fractured young woman. The film explores her internal world with intensity, revealing a character who’s been emotionally starved, psychologically wounded, and socially invisible.

As Psychology Today notes, fairy tales often mirror real-life psychological struggles, especially in how they depict trauma and resilience. This film takes that mirror and smashes it—forcing us to see what’s behind the broken glass.

The ugly stepsister herself isn’t a cartoonish villain anymore. She’s a tragic figure in her own right—jealous, yes, but also desperate to matter. The film’s willingness to humanize her adds nuance and emotional weight.

Dark Cinderella Interpretation – A Mirror to Envy and Survival

This dark Cinderella interpretation gives us a protagonist who isn’t asking for sympathy—she’s demanding recognition. In scenes where she silently observes others at the palace ball, her isolation is palpable. She’s both present and unseen, a walking ghost in satin.

In this version, Cinderella’s rags aren’t symbols of humility—they’re shields. Her silence isn’t gentleness—it’s strategy. She’s been studying those around her for years, waiting for her moment. And when it comes, it’s not about love—it’s about liberation.

This shift in tone parallels trends seen in other modern reimaginings. For instance, the Sundance Institute has highlighted a growing wave of “revisionist fairy tales” that explore female rage, grief, and agency. The Ugly Stepsister fits firmly within this wave—more psychological thriller than bedtime story.

Cinematic Mood and Atmosphere

From its very first frames, the film immerses viewers in a world of heavy shadows and dim candlelight. The set design is minimalist and bleak. Walls are cracked. Ballrooms feel cold. Chandeliers flicker rather than sparkle.

The cinematographer draws inspiration from films like The Witch and Pan’s Labyrinth, creating a visual language that leans into dread. Camera angles are tight, claustrophobic, often shooting Cinderella from behind or in reflection—suggesting her fractured identity.

The score is sparse but chilling. Composer Anya Weiss, whose previous work includes indie psychological dramas, uses violins in sharp dissonance to create unease. Her music punctuates moments of betrayal, sorrow, and subtle power shifts.

The Characters Reframed

Rather than simplifying characters into “good” and “evil,” the film portrays each figure with moral ambiguity.

-

Cinderella: Wounded, calculating, emotionally numb. She learns to manipulate rather than obey.

-

The Stepmother: Not purely cruel, but deeply insecure, terrified of aging and being replaced.

-

The Stepsisters: One is emotionally volatile, the other disturbingly quiet. Both are products of neglect and fierce competition.

In one powerful scene, Cinderella and her stepsister share a moment of mutual breakdown—not in hatred, but in recognition of their shared suffering. It’s a stunning reversal of the traditional dynamic, evoking empathy from even the most cynical viewer.

As Variety reports in its feature on modern fairy tales, “The true monsters are often the systems and silences that create them.” That’s exactly what this film captures.

Themes That Cut Deep

Envy as Inheritance

The film suggests that envy isn’t just a feeling—it’s a family tradition. Passed down from mother to daughter, it corrupts every relationship in the house. Even moments of kindness are shadowed by fear and competition.

Beauty as Weapon

In the palace scenes, beauty is transactional. Cinderella knows this. She wears her gown like armor. Her makeup, when finally applied, feels like war paint. It’s a chilling reminder of how femininity is often treated as currency.

Silence as Resistance

Some of the film’s most powerful scenes are wordless. A look exchanged, a back turned, a tear wiped before it falls. These moments speak louder than any dramatic monologue, revealing how silence can be both submission and defiance.

A Feminist Anti-Fairy Tale?

Yes—and no. While The Ugly Stepsister undeniably critiques patriarchal expectations, it resists simple labels. Cinderella isn’t empowered in the traditional sense. Her choices are morally gray. Her victories are often painful.

Rather than giving us a triumphant heroine, the film offers us someone surviving against the odds—at a cost. This resonates with audiences tired of sanitized girl-power tropes. It dares to ask: What happens when empowerment doesn’t feel good?

The Atlantic argues that “audiences no longer trust pure virtue.” This Cinderella proves that to be true.

Reception and Impact

Film critics at the Tribeca Film Festival were divided. Some called it “a brilliant subversion of myth,” while others found it too bleak. But few denied its power.

Audiences praised its realism, noting how closely it mirrors today’s struggles with mental health, identity, and belonging. College campuses have even hosted panel discussions on its portrayal of family trauma.

One professor at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts noted that, “It’s less a fairy tale and more a cultural reckoning.”

Why It Matters

This film forces us to re-evaluate what stories we pass down and why. It asks uncomfortable questions: Why do we idolize silence? Why do we equate goodness with self-sacrifice? Why must transformation come only through suffering?

By presenting a dark Cinderella interpretation, The Ugly Stepsister invites us to see that resilience can look like rage—and that not every story needs to be wrapped in a bow.

Closing Thoughts

The Ugly Stepsister doesn’t offer closure. It offers honesty. It shows us that fairy tales aren’t always comforting—and that’s okay. In doing so, it doesn’t destroy Cinderella. It revives her.

And in that rebirth, we see ourselves—not as princesses or villains—but as people trying, failing, and surviving in a world that rarely makes sense.

⭐️ MAXMAG Rating: 4.2 / 5

FAQ About the Movie

Q1: What makes The Ugly Stepsister different from traditional Cinderella movies?

Q2: Does the film include a fairy godmother character?

Q3: Is The Ugly Stepsister suitable for children?

Q4: Who directed The Ugly Stepsister?

Q5: Where was the film shot?

Q6: Does the story have a happy ending?